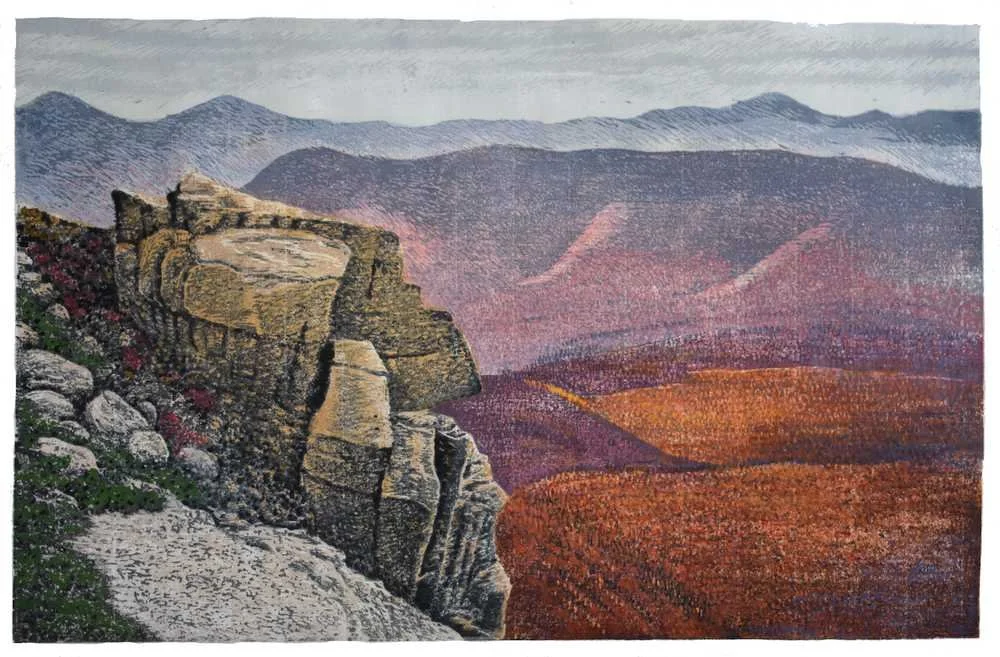

Elemental mountains

“Bond Cliff’ (color woodblock print), on Mt.. Bond in the White Mountains, by Fremont, N.H.-based artist Rick Garber, at New Leaf Gallery, Lyme, N.H.

Above the timber line on Mt. Bond.

Main Street in Fremont, N.H., in 1909.

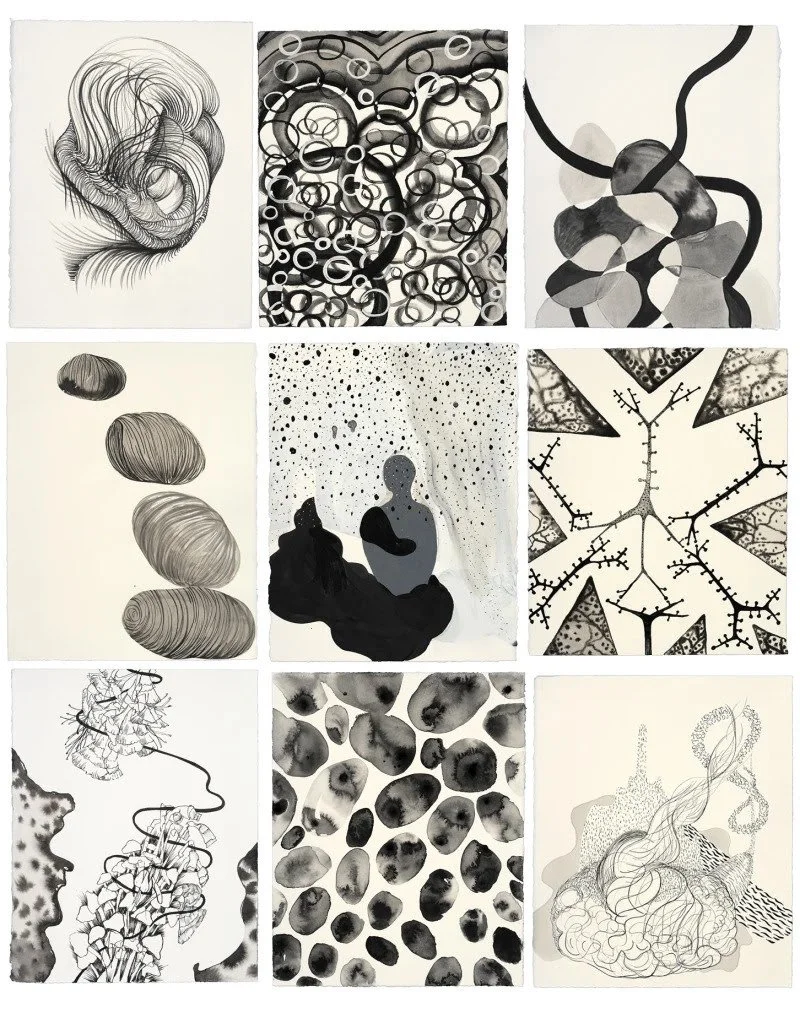

‘Somatic responses’

Selections from Maggie Nowinski’s show “Cicatrix/In Bloom,’’ at Tremaine Art Gallery, at the Hotchkiss School, Lakeville, Conn., through Oct. 15

Maggie Nowinski is a Massachusetts-based multi-modal artist, teaching artist and curator Maggie Nowinski.

The gallery says: “Through her work, Nowinski ‘explores somatic responses to environment, internal and external passageways, and collected disturbances through imagined specimen drawings that depict abject human-botanical entities’ with line drawings, prints, found objects and sound.’’

The Litchfield Hills and Lake Wononscopomuc, as seen from the grounds of the Hotchkiss School, Lakeville, Conn.

Coast in its essentials

“Mother’s Islands” (print) by Swampscott, Mass.-based artist Lydia N. Breed (1925-2019) in the show “Lydia N. Breed: Art of a Community Legacy,’’ at the Lynn (Mass.) Museum, through Sept. 23.

Downtown Lynn. The city once called itself the Shoe (making) Capital of the world.

— Photo by Terageorge

In Swampscott, White Court, now torn down, where President Calvin Coolidge and his wife spent much of the summer of 1925 as the guests of the rich Ohio family who summered there.

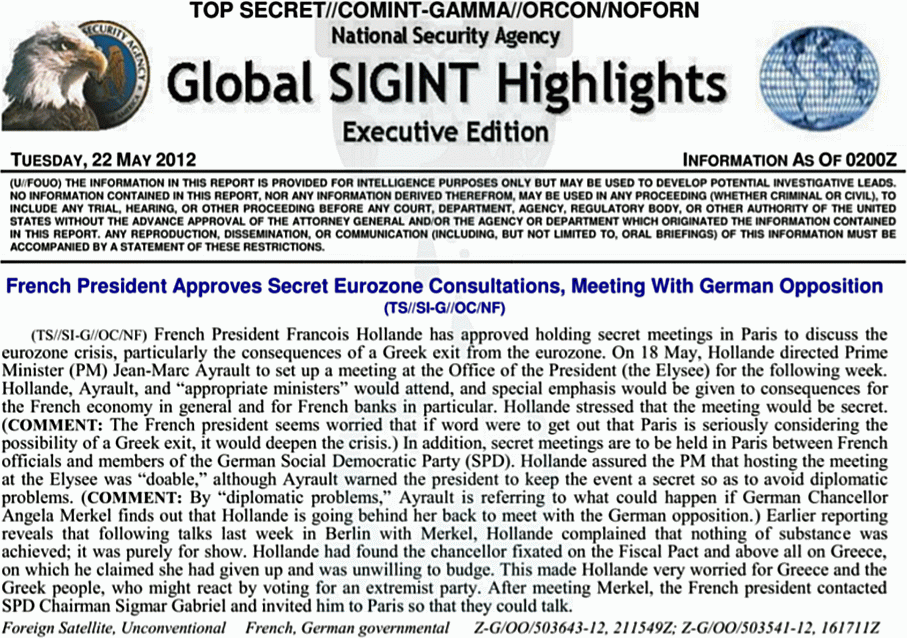

Llewellyn King: My adventures with classified documents

In 1983, Sen. Barry Goldwater (R.-Ariz.) reprimanding CIA Director William J. Casey for Secret information showing up in The New York Times, but then saying it was over-classified to begin with.

It is easy to start hyperventilating over classified documents. It isn’t the classification but what is in the documents that counts. Much marked classified is rubbish.

I have been around the classification follies for years. In 1970, I did what might be called a study, but it was just a freelance article on the use of hovercraft by the military. I was paid $250 to write it.

In those days, there was no easy way to copy a document. The standard was to put several sheets of paper in a typewriter with carbon sheets between them.

Like any other journalist, I started by going to the best library I had access to — in this case, The Washington Post library. I read what was available, largely newspaper clipping, and wrote the article.

Arctic, a consulting company, paid me to write it, and I forgot about it. A couple of years later, I wanted the article — probably to use to get other work — and I asked Arctic for it. They said it had been delivered to the Pentagon long since, and I had better ask the commissioning Department of Defense office.

I did that and was told that I couldn’t have the article, nor could I even look at it because it had been “classified” and I didn’t have clearance.

It had gone, like so much else, into the dark underworld of the classified from whence few pieces of paper ever return.

When James Schlesinger became chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, in 1971, one of the first things he did was to revamp the classification of documents. He told me that the AEC was classifying far more than was necessary and, as a result, the system wasn’t safer but more vulnerable.

His argument was that for classification to work, the people managing classified material had to have confidence that it was truly deserving of secrecy. He directed the declassification of the trivial and increased the security surrounding what was vital.

Schlesinger was succeeded as chairman by Dixy Lee Ray. At the time, I covered the nuclear industry and Ray became a social friend as well as a subject.

Once Ray and I went to dinner at the historic Red Fox Inn in Middleburg, Va. After a swell meal, we walked to her limousine in the parking lot behind the inn. She had something in her briefcase that she wished me to have.

But Ray always had her two dogs with her. One was a huge gray wolfhound and the other was a smaller gray dog, which looked like the wolfhound but was half the size.

The dogs were in the front seat of the car and a high wind was blowing. Ray opened one back door and I opened the other. Then she opened her briefcase and was rifling through the contents — some of which were marked as classified with a telltale, red X — when the big wolfhound jumped onto the back seat. He knocked over the briefcase and the wind blew documents all over the parking lot.

It was a security crisis. Not that Soviet agents were dining at The Red Fox Inn that night, but if any document marked as secret was found and handed to the police, a major scandal would have resulted.

For the best part of an hour, Ray, myself and her driver scoured the parking lot, the grassy areas and the bushes for documents.

In the early morning, I drove back to the inn to make sure we had made a clean sweep. State secrets in the parking lot of a pub make for hot headlines and end careers.

In the age of computers, classified documents — and who knows if they should be marked as such — are much less likely to be put into paper folders.

Once the Congressional Joint Committee, which oversaw the Atomic Energy Commission, held a hearing in its secure hearing room in the U.S. Capitol, where all the documents before the members and the witnesses were marked “eyes only.” The hearing had to be canceled because no one could say anything.

Also, once at one of the major nuclear-weapons laboratories, I deduced what a machine I was told was used for conducting “scientific experiments” really was. The director assured the technician showing it, “Don’t worry, King is too stupid to know what it is.” He was right and another state secret was saved.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Federal container for storing classified documents.

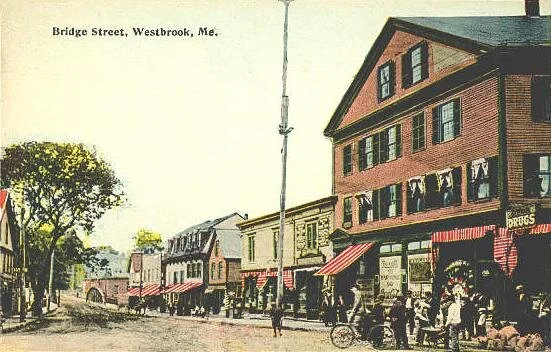

Abstracted walk in the woods

“Lookout” (acrylic on canvas), by Liz Hoag at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Hoag [based in Westbrook, Maine} is inspired by her walks in the Maine woods and is known for her abstracted tree-filled landscapes that give the viewer a glimpse of the hidden vignettes that exist in the forest but are often overlooked. She begins her compositions with dark canvas and builds light tones on top of the dark creating the positive space in the composition. The result is a painting that conveys the beauty of light filtering through trees and the serenity one feels on a walk in the woods.’’

This sign and gazebo are across the street from the Westbrook Public Library. The mural was a project of Westbrook Arts & Culture, painted by aerosol artist Mike Rich and funded by the Warren Memorial Foundation and several Westbrook businesses. See the old mill building in the distance.

Westbrook is an old mill town and now mostly just seen as a suburb of Portland.

Bridge Street in Westbrook in 1912

David Warsh: Economic complexity and price revolutions

— Graphic by Hiroki Sayama

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I listened idly as two old friends hashed over the argument between Larry Summers and Biden administration officials about the inflationary potential of continuing low interest rates. This, I thought, was where I had come in. My mind drifted back to the book I published in 1984, The Idea of Economic Complexity.

Its premise was what I took to be the similarity between the “price revolution” of the 16th Century and that of the 20th. In the century and a half between 1500 and 1650, everyday prices across Europe had risen roughly six-fold, before settling on a new plateau. Theory usually ascribed these otherwise baffling developments to the importation of New World treasure and improvement in mining techniques: too much money chasing too few goods.

In the fifty years after World War II, costs of living grew as much as five- or ten-fold, depending on how which costs were measured, before leveling off again. This time opinions were divided. “Keynesians” emphasized political pressures, “cost-push” factors in some instances, “demand-pull” episodes in others. “Monetarists” insisted central bankers’ increases in the quantity of money were to blame.

In The Idea of Economic Complexity, I suggested picking up the other end of the stick. Perhaps changes in the world economy had been at the heart of both price explosions: the settlement of the New World, the development of the slave trade, and the rise of the middle class in the 16th and 17th centuries; democratization, urbanization, globalization and the growth of government in the 20th.

The book convinced few. I gradually became interested in what economists seem to understand pretty well already: prices and quantities, trade policy, economic history, social welfare. In all the years since, I have made only one advance in speaking more clearly about what might be meant by “economic complexity.” Economic complexity is surely complexity of the division of labor.

At some point the acuity of Adam Smith’s dictum that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market was borne in on me. There are other ways of maintaining the division of labor, chiefly taxes. Even in wartime, though, taxes, too, depend on the extent of the market.

How might the division of labor be described? One promising beginning employs network theory. An alternative, suggested by Eric Beinhocker, in The Origin of Wealth: The Radical Remaking of Economics and What It Means to Business and Society (2007) sought to apply the mechanisms of biological evolution. In that case, cladistics and other systems of phylogenetic nomenclature are worth exploring. For managers of a monetary system to efficiently control a global division of labor of evolving complexity, they must know something about complexity itself.

Economics has made great strides borrowing analytic techniques from pneumatics and celestial mechanics. There is probably something to be learned from evolutionary biology as well. It was here, and to Peter Blume’s painting. “The Parade,’’ on the jacket of The Idea of Economic Complexity, that my mind wandered while my friends debated fiscal pressures.

Economic journalism has plenty of first-rate reporters at work in financial capitals around the world, but the Covid pandemic has been as hard on those of us who interested in taking stock of longer trends. Get ready for a spate of books – some of them probably quite good – about the significance of digital and crypto-currencies for money. Complexity was a young man’s book. The next book here – the last – will be different altogether.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this columnist originated.

Llewellyn King: Sanders's economic fantasyland

From The Violet Fairy Book (1906)

It’s hard for me to believe that Donald Trump is president. Really hard. Equally hard for me to believe that Bernie Sanders is the Democratic front-runner, especially after the Las Vegas debate.

I can take Sanders’s passion, although it’s so consuming it gets to be frightening. I can take his calling himself a democratic socialist, although I don’t know to what extent his form of socialism pits him against capitalism. Enough, I fear.

Some of what Sanders had to say in Las Vegas was downright risible, or has been tried and failed, or, worse, would set in place a series of negative dynamics, damaging the country in many ways without bringing about any of the gains he wishes to achieve. Listening to him, I think, “This donkey wants his feedbag.”

In his way, Sanders is as committed to conspiracy theories as is Trump. Sanders sees vast, secretive forces in fossil-fuel companies, lobbyists, bankers and billionaires as being united in a scheme to keep the rest of us poor and ill-served by government.

Here are three of his big fallacies:

1. Companies would be better if they were partly owned by the workers. This is real socialism and it hasn’t worked when it’s been tried.

Sanders would be well-advised to read up on the history of the cooperative movement in Britain. The very first casualty would be innovation because worker governance isn’t risk-taking.

I say this having been very familiar with the British coop movement and having headed a trade union local, the Newspaper Guild, in Washington. Collective decision making is not creative, risk-taking or forward-looking.

2. The technology of fracking to extract oil and natural gas from tight rock formations should be stopped in order to combat global warming. That would deal the economy a body blow while doing nothing for global warming.

Carbon emissions from fossil fuels are coming down, and on the horizon is the technology of carbon capture, utilization and storage and other technological fixes for carbon emissions.

Technology has enabled fracking and technology, not cessation, will clean up emissions.

3. The current health-care mess should be replaced root-and-branch by a national health system. That we need a stabilizing public option in health care is more apparent daily. But health reform needs to be introduced like good medicine, prudently with the dosage corrected in relation to the progress of the patient.

Sanders’s approach to most issues can be summed up by what author H.G. Wells, a socialist, said of playwright G.B. Shaw’s ideas. He said the trouble with Shaw, also a socialist, was that Shaw wanted to cut down the trees to erect metal sunshades. Quite so.

In Las Vegas, Sanders was out to cut down every tree he could see. These included what is part of the American Dream: Anyone with pluck and hard work can improve their situation, and maybe grow rich.

Sanders’s assault on Mike Bloomberg was that Bloomberg didn’t accept some mythical belief that money is inherently bad and that those who’ve made a lot of it are evil and constantly conspiring to keep the rest of us in penury — at least those who earn up to the Senate salary of $174,000 a year.

The long-term evil of money isn’t in the generation that makes it, but in the families that will inherit it down through the generations, creating an oligarchy the likes of which we haven’t seen since the fall of the serf-exploiting Russian nobility.

Someone should take Sanders on one side and tell him about failed experiments in worker ownership, the value of evolution over revolution, and that every American would like to be rich.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.