Llewellyn King: In ‘25 we lost the metaphor of America

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Come on in, 2026. Welcome. I am glad to see you because your predecessor year was not to my liking.

Yes, I know there is always something going on in the world that we wish were not going on. Paul Harvey, the conservative broadcaster, said, “In times like these, it helps to recall that there have always been times like these.”

Indeed. Wars, uprisings, oppression, cruelty and man's inhumanity to man are to be found in every year. But last year, the world lost something it may not get back. You see, '26 — you don't mind if I shorten your title, do you — we lost America. Not the country but the metaphor.

We were, '26, despite our tragic mistakes — including slavery and wrongheaded wars — a country of caring people, a country that cared (mostly) for its own people and those who lived elsewhere in the world.

It was the country that sought to help itself and to help the world. It was the sharing country, the country that showed the way, the country that sought to correct wrong, to overthrow evil and to excel at global kindness.

It was the country that led by example in freedom of speech, freedom of movement and in free, democratic government.

When John Donne, the English metaphysical poet, described his lover's beauty as ‘‘my America" in the 1590s, he foreshadowed the emergence of the United States a nation of spiritual beauty.

From World War II on, caring was an American inclination as well as a policy.

We helped rebuil Europe with the Marshall Plan, an act of international largesse without historical parallel. We rushed to help after droughts, fires, earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis and wars.

We were everywhere with open hands and hearts. America the bountiful. We had the resources and the great heart to do good, to show our own overflowing decency, even if it got mixed up with ideology. We led the world in caring.

We bound up the wounds of the world, as much as we could, whether they were the result of human folly or nature's occasional callousness.

We delivered truth through the Voice of America and aid through the U.S. Agency for International Development. Our might was always at hand to help, to save the drowning, to feed the starving and to minister to the victims of pandemic — as with AIDS and Ebola in Africa.

In 2025, that ended. More than a century of decency suspended, suddenly, thoughtlessly.

America the Great Country became America Just Another Striving Country, decency confused with weakness, indifference with strength, friends with oil autocracies.

It wasn't just the sense of noblesse oblige, which not only distinguished us in the 20th Century, but also earlier. In the 19th Century, we opened our gates to the starving, the downtrodden and the desperate. They joined the people already living here to build the greatest nation — a democracy — that the world has ever seen. First in science. First in business. First in medicine. First in agriculture. First in decency.

These people brought to America labor and know-how across the board, from weaving technology in the 18th century to engineering in the 19th century to musical theater in the 20th century, along with movie-making and rocket science.

I would submit, '26, that it is all about American greatness, and last year we slammed the door shut on greatness, abandoned longtime allies and friends. We forsook people who had been compatriots in war, culture and history for the dubious company of the worst of the worst, aggressors, oppressors, liars, everyone soaked in the blood of their innocent victims.

Yes, '26, America stood tall in the world because it stood for what was right. Its system of law — including the ability to have small wrongs addressed by high courts — was the envy of foreign lands where law was bent to politics, where democracy was an empty phrase for state manipulation of the vote. The Soviet Union claimed democracy; America practiced it.

America soared, for example, with President Jimmy Carter's principled and persuasive pursuit of human rights and President Ronald Reagan's extraordinary explanation of its greatness: the “shining city upon a hill.”

It sunk from time to time. Slavery was horrific; Dred Scott, appalling; Prohibition, silly; the Hollywood blacklist, outrageous.

But '26, decency finally triumphed and America was great, its better instincts superb — and now worth restoring for the nation and for the troubled, brutalized world.

Good luck, '26. You will bear a standard that the world has looked to. Lift it high again.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Based in Rhode Island, he’s also an international energy-sector consultant and speaker.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King: In 2026, 70 percent effort should be enough

An ice sculpture for First Night in Boston

A remarkable autobiography by Anthony Inglis, the English conductor and musicologist, is titled, Sit Down, Stop Waving Your Arms About! Quite so.

This admonition occurred while Inglis was conducting a musical. Someone sitting in the front row tapped him on the shoulder and told him to sit down and stop waving his arms about.

My admonition to you for the new year is to sit down and stop stressing yourself.

We are plagued with the idea of stress, and yet we start the new year with resolutions. We order a raft of these stress-making endeavors.

Want a stress-free new year? Stop your New Year's resolutions right now.

Do you need to tell yourself that you will stay on your diet? No. You won't anyway.

Do you need to set a goal of going to the gym five times a week? No. You won't get to Planet Fitness more than once or twice, in the whole year.

So, your desk looks like a dump, leave it alone. You will promise yourself that for the first time ever you will get organized in 2026. You won't. So why get stressed about it?

You have promised yourself that this year you are going to improve your mind and read 20 great books. You won't. Best case, you will flip through a James Patterson thriller or a Danielle Steel romance. Maybe the detective novel you purchased at an airport will make it to your nightstand, alongside the classic you plan to read when you get around to it. That is never, so get rid of that reproving volume. Give it to charity. You will shed stress and feel good at the same time by doing that.

Sloth clothed as virtue is so, so stress-relieving.

Put aside the stress of resolutions in the new year and relax into a year of self-indulgence.

If a work colleague comes over to you and starts talking about productivity, cross your arms, sit down and, if your system allows, break wind.

Approach work as a card-carrying slough-off. In the Soviet Union, which was supposed to be the “workers' paradise,” workers used to say, “They pretend to pay us and we pretend to work.” Good on them.

If striving is pointless, stop striving. Give it a rest.

I suggest that there is a terrible national lack of malaise. At every turn, we are urged to learn more, work harder and innovate, innovate, innovate. You don't need innovation to have a second helping, open a beer or take the day off.

You may need to be a little innovative, explaining why you aren't at work. But that isn't so hard: Claim a mental-health day. Particularly if you are well and fit enough to enjoy it at the beach, at a movie theater or snuggled down into your bed.

If people are telling you to “lean in” and “try harder or the Chinese will get ahead,” go to dinner at a Chinese restaurant and wonder at the number of dishes which can be prepared almost instantly — none of which you would cook. Then conclude that the Chinese have already won and stop stressing.

Think back to when we stressed mightily about the Japanese and the Germans beating us at everything. Then enjoy a suffusing, warm gladness when you realize that all that leaning in and trying harder hasn't helped them beat us. Maybe we should have a national academy for failing upward.

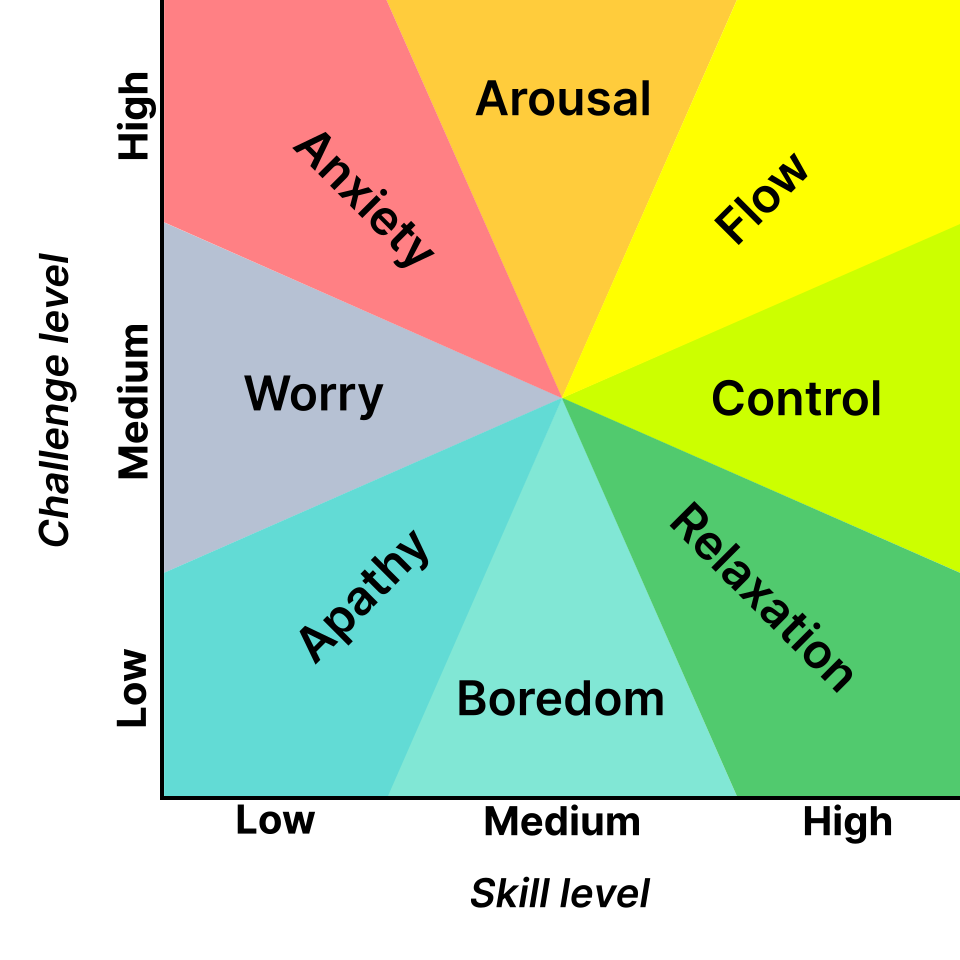

Lloyd Kelly, a fine artist and a friend, teaches Tai Chi in Louisville, Ky., particularly in one of the city's hospitals. He advises his students — some of whom are in wheelchairs — to stay within their comfort level, “to give just 70 percent.”

There is something beautiful about that admonishment at a time when people are stressed out and society is mindlessly urging you to struggle, to achieve, to conquer.

Here, then, is a resolution you can keep: I am only going to give a 70 percent effort. That way, perchance, you will have a great new year by default.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

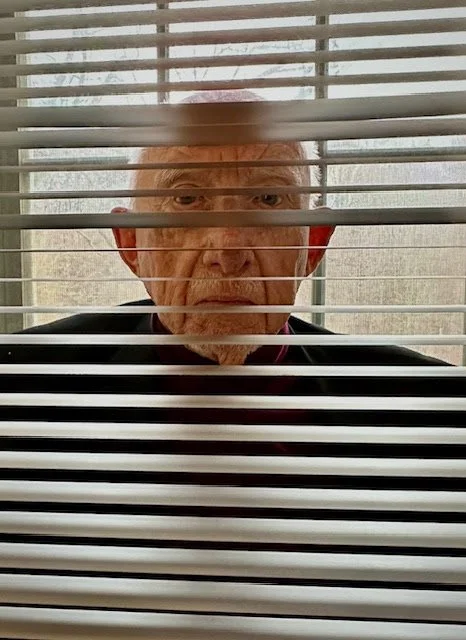

Llewellyn King: Trump gave us a year of fear: And 2026?

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Of all the things that happened in 2025 — a year dominated by the presidency of Donald Trump — not the least is that great fear came to America.

It's reminiscent of the fear that African-Americans knew in the days of the lynch mob, or that Jews have felt from time to time, or that Hollywood felt during the blacklist of the 1940s and 1950s, or the fear that people of Japanese descent from the West Coast, who were mostly U.S. citizens, felt when they were rounded up and interred following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

For some, it is a low-grade fear of reprisals, financial ruin and humiliation. And for some, it is a fear of ruin by litigation. But for others, it is fear of faceless arrest, the jail cell and plastic handcuffs.

All of this has made us a nation in fear and removed our faith in our laws, our Constitution, and our plain decency.

This is a new kind of fear that is acute in places, such as immigrant communities, but more universal than in the past.

It isn't the fear of a foreign power or an alien ideology or a disease, but a fear generated domestically — generated by our own government. Fear in our workplaces, our schools, our movie studios, our newsrooms and our universities.

For the first time, this year we saw troops on the streets of cities when there was no civil unrest — as there was, for example, during the riots of 1968, which followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

We saw troops deployed in cities where they weren't wanted, opposed by the local government and local people. But those cities got the troops courtesy of an assertion by the president that troops can manage law enforcement better than the local police. Or was there some more sinister purpose?

For the first time, we saw arrests without charge or evidence, carried out by masked ICE agents, of people simply suspected of being here illegally.

Often the suspicion is no more than the color of the arrestee's skin, their dress and their demeanor. No crime needs to be proved by this army of the state, dressed to intimidate. To the ICE men and women, appearance is tantamount to conviction.

Nightly on television we watched agents drag away men, women and children without due process; they would been held and deported without charge, trial or having any avenue of appeal. Justice denied, nonoperational. Often deportees go to countries that are alien or different from their homelands.

Fear has come home.

Immigrants are frightened even if they are citizens. If you have olive-toned skin, you can be dragged and held incommunicado. No appeal, no trial, no court appearance, no access to help. Habeas corpus suspended.

Pinch yourself and ask: Is this the America we cherish for its freedom, its justice and its generosity of spirit?

The fear isn't confined to those who might be swept up in the mindless cruelty of ICE but extends throughout society. People with stature fear that if they speak out, if they do what at other times they might have seen as their civic duty, they will endanger themselves and their families. All the government has to do is to start an investigation or threaten one and the damage is done, the first level of punishment is delivered.

Investigations can target anything from how you filled out a mortgage application to whether you wrote something that may be viewed as objectionable, and the punishment begins.

Fear stalks the schools where teachers and professors can be punished for what they say or teach, and where the institutions of higher learning are subject to political scrutiny. Politics has become the law, capricious and savage.

There is fear in business, where so many companies rely on government loan guarantees or tax credits for their growth. There is fear that if they say anything that can be construed as disloyal, they will be punished.

Political opponents fear that their mortgage applications may be deemed to be irregular and they are to be censured or prosecuted. Political prosecution is now a government tool.

Others just fear that Trump will ridicule them in public with his schoolyard denigrations, particularly members of Congress. They fear they will be reprimanded and marked for defeat in the polls.

There is an awful completeness about the Trump rampage: his systematic ignoring of norms, shredding of the rights of the individual, destroying families and bringing about untold misery.

A question for all America: How is the spreading of fear — sometimes an acute fear and sometimes low-grade fear — throughout society beneficial and to whom?

We, the people, deserve to know.

X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

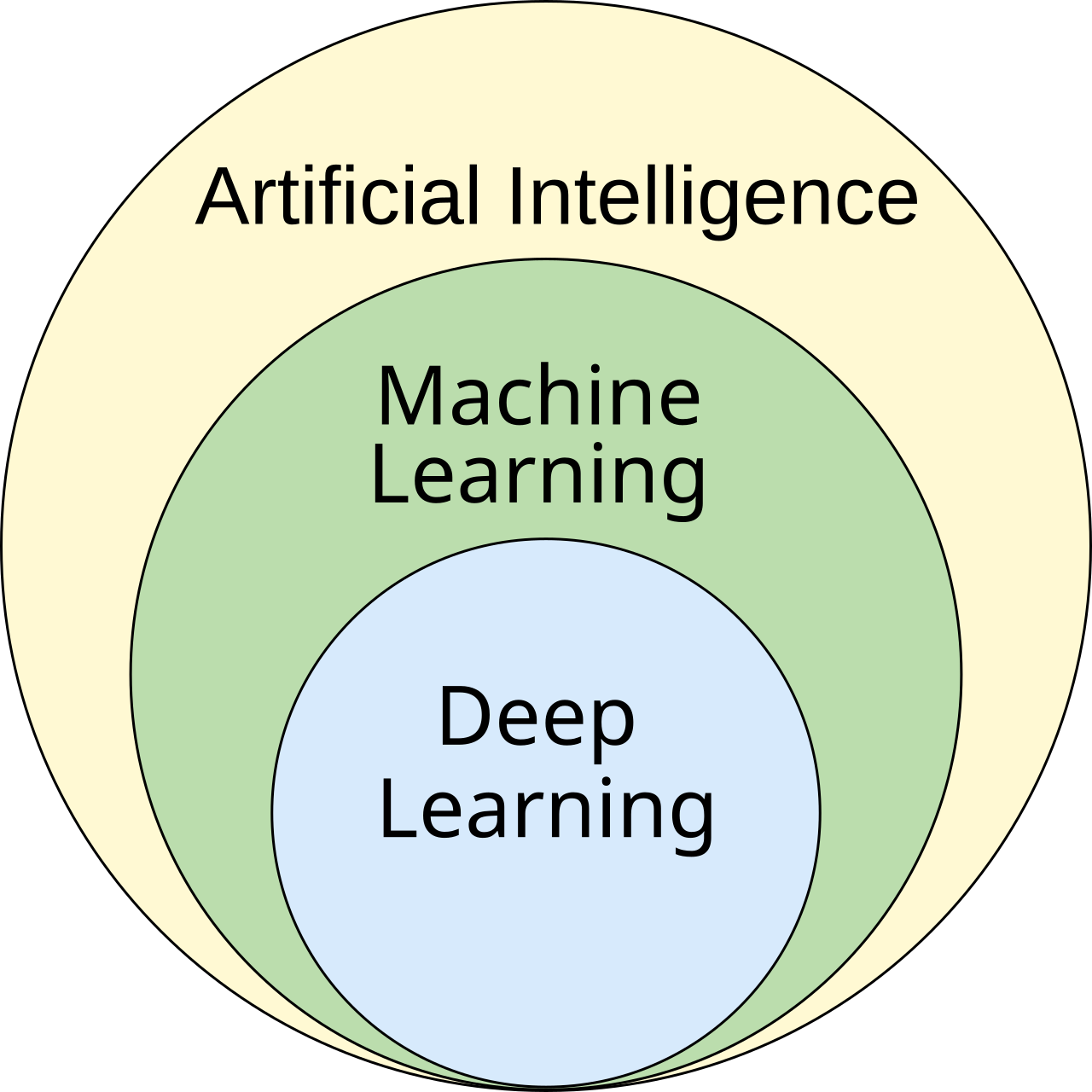

Llewellyn King: AI and our robotic future

The robot Maria from the 1927 German expressionist film Metropolis

Editor’s Note: Visit the fabulous MIT Museum, in Cambridge, Mass., to check robotic-related stuff.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The next big thing is robots. They are, you might say, on the move.

Within five years, robots will be doing a lot of things that people now do. Simple repetitive work, for example, is doomed.

Already, robots weld, bolt and paint cars and trucks. The factory of the future will have very few human workers. Amazon distribution centers are almost entirely robot domains. Robots search the shelves, grab items, pack and send them to you — often seconds after you have placed your order.

Of course, these orders will be delivered in vans, which must be loaded carefully, even scientifically. The first out must be the last in; small items must nestle with large ones. Space is at a premium, so robotic brains will do the sorting and packing swiftly, efficiently and inexpensively.

Very soon, the van will be self-driving: a robot capable of navigating the traffic and finding your home. At first, it may not get further in the delivery chain than calling you to say that your package has arrived. Eventually, humanoid robots may ride in the vans and, yes, hand your package to you. No tipping, please.

When we think about robots, we tend to think of the robots that look like us. The internet is full of clips of them climbing stairs, playing sports and doing backflips.

There are reasons for humanoid robots: They are less intimidating with their humanlike heads, two arms with hands and two legs with feet than a machine with many arms or legs. Also, most of the tasks the robot is taking over are done by humans. The tasks are fitted to people, such as pumping gas, preparing vegetables or painting a wall.

The first big incursion may be robotaxis. Waymo taxis are already operating in five cities, and the company has plans to roll them out in 19 cities. Several cities are concerned about safety, including Houston and Seattle, and want to ban them. But there are state-city jurisdictional issues about implementing bans.

A likely scenario, as with other bans, is that the development will go elsewhere. Travelers tend to eschew places where Uber and Lyft aren’t allowed to operate in favor of those where they are.

You are already dealing with robots when you talk to a digital assistant at an airline, a bank, a credit card or insurance company, or any business where you call a helpline. That soothing, friendly voice that comes on immediately and asks practical questions may be a robot: the unseen voice of artificial intelligence.

In the years I have been writing about AI and its impact on society, I have consistently heard the AI revolution and its impact on jobs compared with the Industrial Revolution and automation. The one led to the other and in the end, many new jobs and whole new ecosystems flourished.

It isn’t clear that this will happen again and if so on what timetable. A lot of jobs are already in danger, from file clerks to delivery and taxi drivers, from warehouse workers to longshoremen.

AI is also changing the tech world. A whole new tier of companies is emerging to carry forward the AI-robot revolution. These are companies that make robots; companies that write software, which will give robots brainpower; and companies that will have a workforce that maintains robots.

These emerging companies will need a workforce with a different set of skills — skills that will keep the new AI economy humming.

What is missing is any sense that the political class has grasped the tsunami of change that is about to break over the nation. In just a few years, you may be riding in a robotaxi, watching a humanoid robot doing yard work or lying on a couch and chatting with your robot psychiatrist.

Our species is adaptable, and we have adapted everything from the wheel to the steam engine to electricity to the internet. And we have prospered.

Time to think about how to prosper with AI and its robots.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, as well as an international energy-sector consultant. He’s also a former publisher and editor.

Llewellyn King: Journalism is a business of serial judgment under pressure

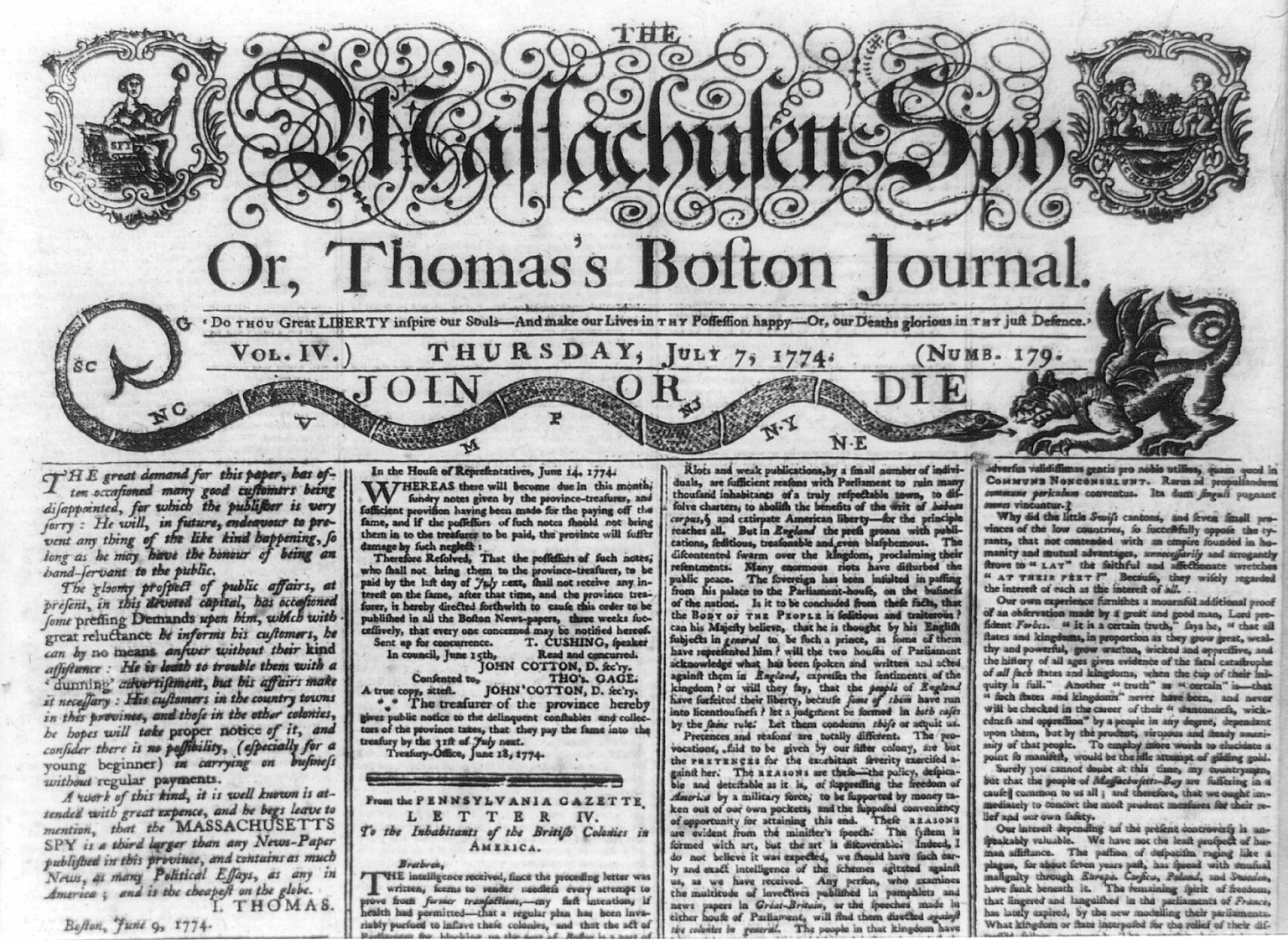

An example of the nonobjective newspapers that dominated American journalism until ideals of objective rep0rting slowly started to take hold around the turn of the 20th Century in larger cities.

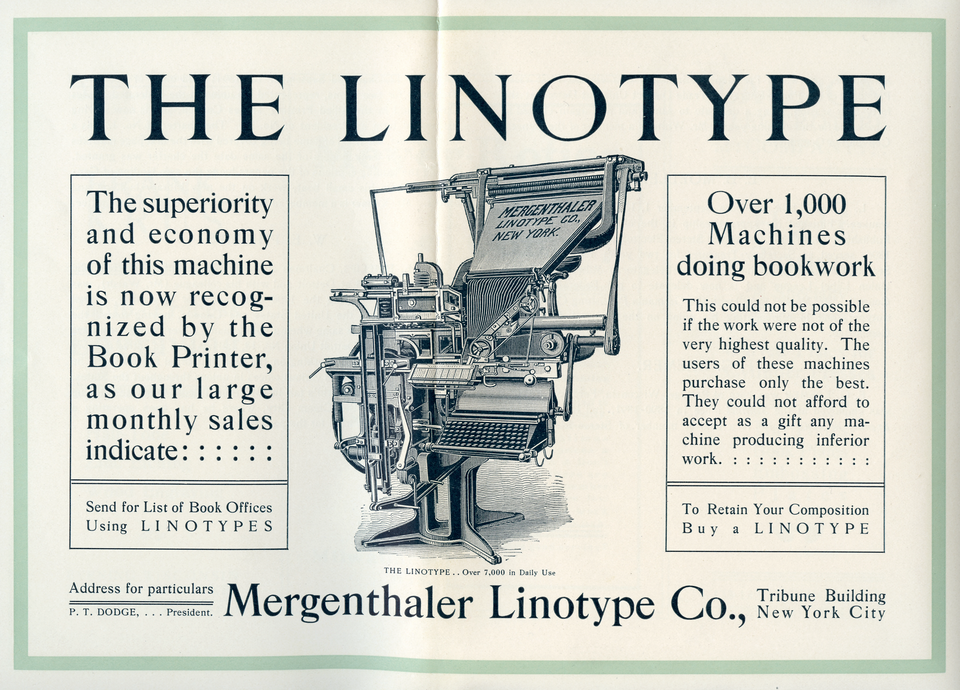

The Linotype machine was very important in newspaper printing until computerization doomed it.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The BBC has fallen on its sword. The director general has resigned and so has the head of news over the splicing of tape of President Trump's rambling speech on Jan. 6, 2021, which preceded the sacking of the Capitol by his fanatical followers.

The editor and the technician who did the deed for the esteemed BBC program Panorama haven't been publicly identified.

Agreed, they shouldn't have done what they did. But was there malice?

Journalism is a business of serial judgment. It is replete with mistakes — things that we who practice the craft wish we hadn't done.

I have worked as an editor in film, with tape and on newspapers, and I have seen how the paranoia of politicians can cast a whole news organization as a biased enemy when that wasn't the case.

Before a single sentence or an article appears in a newspaper or a video appears on television, dozens of judgments have been made — not by teams of academics or by ethicists or by juries, but by individuals responding to time pressure and what they judge to be newsworthy.

The unsaid pressure to keep it interesting, to have news worth something, is always there. The reader has to be kept reading or the viewer watching.

After something is published or broadcast, it can be beacon-clear what should have been done or corrected, but in the moment, those defects are opaque.

Let me take you behind the veil.

It is a hot night in 1972. There is a presidential election brewing and among those running for the Democratic nomination is Henry “Scoop" Jackson, the well-known Democratic senator from the state of Washington.

I am working in the composing room of The Washington Post as the editor in charge of liaising between the printers and the editors. The job is sometimes called a stone editor after the “stone’’ — big metal tables that held the pages and where the newspaper was assembled in the days of hot type via Linotype machines.

It was a busy news night, and it was when David Broder was the political reporter without rival. He was industrious and thorough, dedicated and prolific. As the night wore on, Broder would often add new stuff to his story, and it would grow in length.

In desperation when things got tough and deadlines were pressing, we would cut back the size of the photos, which had run in the first edition. The editor on duty would just ask the printers to do this: It was known as “whacking the cut."

In short, the photo would be reduced in size by cutting it down physically. The engraving would be put in a guillotine and some of it would be cut off, whacked.

That night, we had a large photo of Jackson addressing a large crowd.

But as the night wore on and different editions and mini editions, known as replates, were assembled, I ordered the cut whacked and whacked again. The result was that by the time the main edition went to press, the good senator was talking to a much smaller audience — although it did suggest that many more were there but not seen.

Jackson thought that this was a deliberate bias by The Post to suggest that he couldn't draw a large audience, and he called the legendary executive editor Ben Bradlee.

Bradlee asked the national editor, Ben Bagdikian, who was to become an authority on newspaper ethics, what happened. When they came to me, I explained how we trimmed the pictures.

While Bradlee was amused, Bagdikian added it to his concern about newspaper ethics.

Journalism is executed by individuals under pressure, much of it intense. It is a business of multiple judgments made sequentially, often without a lot of contemplation.

I once worked at the BBC in London, and the same pressures were present. I was scriptwriter and editor on the evening news. You made decisions all the time: This frame in, those 20 frames out. An outsider might imagine prejudice and foul intent in the way one clip was used and others were not.

In the news trade, judgments can trip you up, but making judgments is essential. Later the judge is judged, as at the BBC.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based mostly in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He was a long-time publisher and remains an international energy-sector consultant.

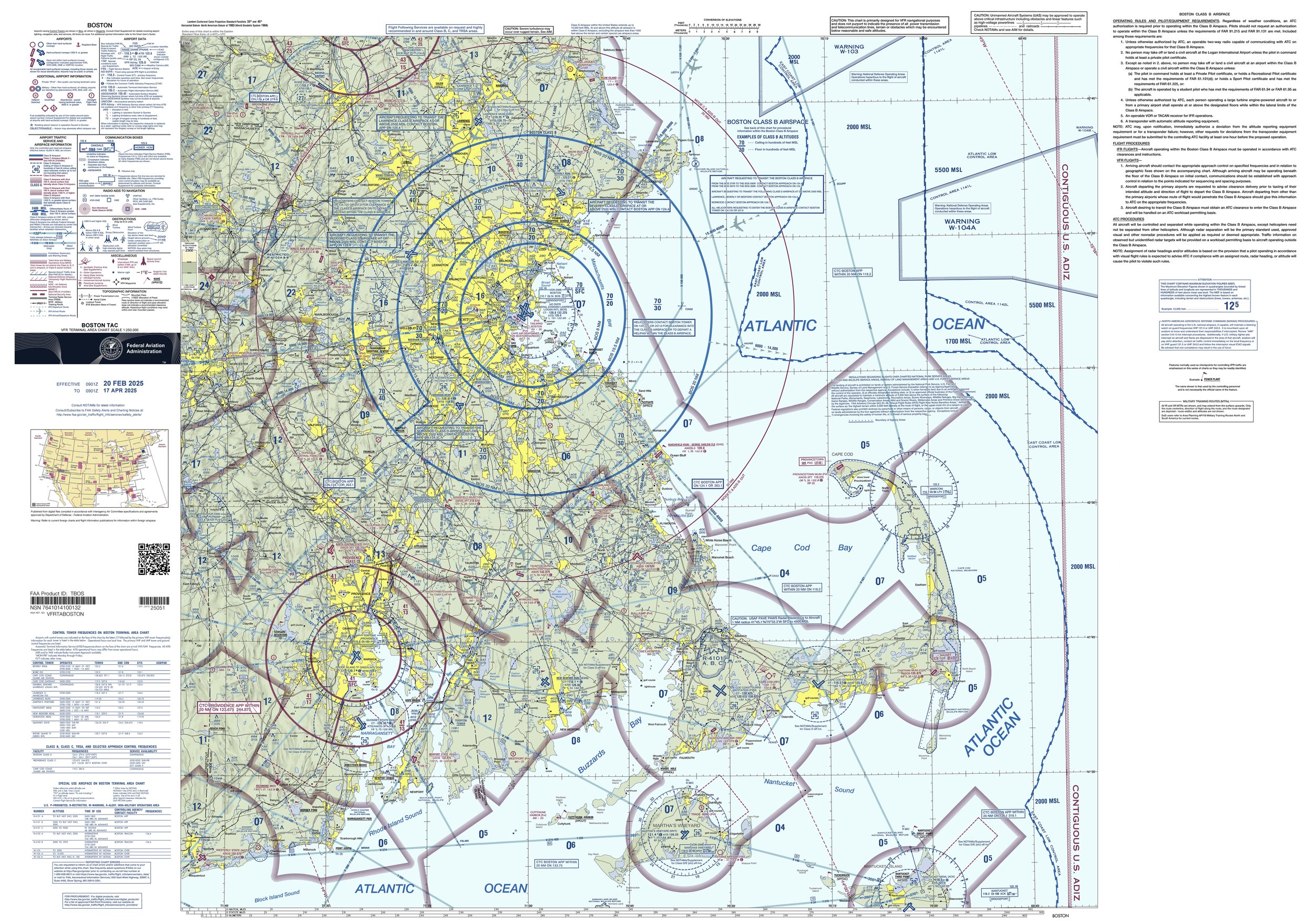

Llewellyn King: The biggest sources of stress for air-traffic controllers

Air-traffic-control zones in the southeast corner of New England.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If you don't know about the stress that air-traffic controllers are reportedly under, then maybe you are an air-traffic controller.

The fact is that air-traffic controllers love what they do — love it and wouldn't do anything else.

The stress comes with long hours, Federal Aviation Administration bureaucracy and a general lack of recognition, not with moving airplanes safely about the sky.

Of course, I haven't interviewed every controller, but I have talked to a lot of them over the years and have been in many control towers.

Controllers love the essentiality of it. They love aviation in all its forms.

They love the man-and-machine interface, which is at the heart of modern aviation. They love the sense of being part of a great system — the power, the language, the satisfaction.

They love the trust that every pilot puts in them. It is rewarding to be trusted in anything, but more so when the price of failure is known.

Nearly everything that is true of pilots is true of controllers. At its heart, the job is about flight, arguably the greatest achievement of mankind, the fulfillment of millennia of yearning.

There is a saying often attributed to Winston Churchill that was actually said by a pilot and insurance executive in the 1930s: “Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

That is true both of pilots and those at the consoles on the ground, who co-fly with them.

After President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking controllers in 1981, some of the saddest people I knew were air-traffic controllers.

They were denied the right to do the work that they loved and suffered immeasurably for that. A few were able to get work overseas, but mostly it was a light that went out and stayed out.

I ran into one former controller, working as a baggage handler. He said he just wanted to be near the action even if he couldn't go into the tower anymore and do his dream job.

My only major criticism of Reagan in this case has always been that he didn't rehire the strikers after he had won, proving that they were wrong in striking illegally and that they weren't above the law.

Reagan was often a compassionate man, but he showed the controllers no compassion. I think that if he had understood the psychological pain he had inflicted, he would have relented.

Controllers have explained to me that if a controller finds the job stressful, then he or she shouldn't be a controller.

About one-third of the candidates for controllers' school, most of whom are trained at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, flunk out.

It takes longer to train a controller than a pilot — maybe not to work in the cockpit of a passenger jet, but certainly to fly an aircraft, including jets. It takes at least four years of schooling, simulator and then supervised controlling to qualify to be an FAA controller. Some controllers come from the military.

There is just one movie about air-traffic control, released in 1999, Pushing Tin. It flopped at the box office but has a cult following among pilots and controllers. It is funny and accurate. Pushing tin is controllers' jargon for what they do: push airplanes around the sky.

The fabled stress, in my mind, is the adrenaline factor. It is present in air-traffic control, and it is present in the cockpit of everything that leaves the ground, from single-engine Cessnas to Boeing 777s — and in ATC facilities.

It interests me that pilots rarely mention stress. It is, however, always mentioned by people writing about or talking about air-traffic control. I would venture that the most stress that controllers deal with is the stress imposed on them by the FAA.

I will aver that in the recent and record-long government shutdown, the largest source of stress for controllers was how they were going to put food on the table and pay their bills, not the stress that they feel at the console, pushing tin and keeping flying safe. Now they are stressed about back pay.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Can the elephant of AI become capable of policing itself?

Street art in Tel Aviv.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

For me, the big news isn't the politics of the moment, the deliberations before the Supreme Court or even the news of the battlefront in Ukraine. No, it is a rather modest, careful announcement by Anthropic, the developer of the Claude suite of chatbots.

Anthropic, almost sotto voce, announced it had detected introspection in their models. Introspection.

This means, experts point out, that artificial intelligence is adjusting and examining itself, not thinking. But I don't believe that this should diminish its importance. It is a small step toward what may lead to self-correction in AI, taking away some of the craziness.

There is much that is still speculation — and a great deal more that we don't know about what the neural networks are capable of as they interact.

We don't know, for example, why AI hallucinates (goes illogically crazy). We also don't know why it is obsequious (tries to give answers that please).

I think that the cautious Anthropic announcement is a step in justification of a theory about AI that I have held for some time: AI is capable of self-policing and may develop guidelines for itself.

A bit insane? Most experts have told me that AI isn't capable of thinking. But I think Anthropic's mention that introspection has been detected means that AI is, if not thinking, beginning to apply standards to itself.

I am not a computer scientist and have no significant scientific training. I am a newspaperman who never wanted to see the end of hot type and who was happier typing on a manual machine than on a word processor.

But I have been enthralled by the possibilities of AI, for better or worse, and have attended many conferences and interviewed dozens — yes, dozens — of experts across the world.

My argument is this: AI is trained on what we know, Western Civilization, and it reflects the biases implicit in that. In short, the values and the facts are about white men because they have been the major input into AI so far.

Women get short shrift, and there is little about people of color. Most AI companies work to understand and temper these biases.

While the experiences of white men down through the centuries are what AI knows, there is enough concern about that implicit bias that it creates a challenge in using AI.

But what this body of work that has been fed into AI also reflects is human questioning, doubt and uncertainty.

At another level, it has a lot of standards, strictures, moral codes and opinions on what is right and wrong. These, too, are part of the giant knowledge base that AI calls upon when it is given a prompt.

My argument has been: Why would these not bear down on AI, causing it to struggle with values? The history of all civilizations includes a struggle for values.

We already know it has what is called obsequious bias: For reasons we don't know, it endeavors to please, to angle its advice to what it believes we want to hear. To me, that suggests that something approximating the early stages of awareness is going on and indicates that AI may be wanting to edit itself.

The argument against this is that AI is inanimate and can't think any more than an internal combustion engine can.

I take comfort in what my friend Omar Hatamleh, who has written five books on AI, told me: “AI is exponential and humans think in a linear way. We extrapolate."

My interpretation: We have touched an elephant with one finger and are trying to imagine its size and shape. Good luck with that.

The immediate impact of AI on society is becoming one of curiosity and alarm.

We are curious, naturally, to know how this new tool will shape the future as the Industrial Revolution and then the digital revolution have shaped the present. The alarm is the impact it is beginning to have on jobs, an impact that hasn't yet been quantified or understood.

I have been to five major AI conferences in the past year and have worked on the phones and made several television programs on AI. The consensus: AI will subtract from the present job inventory but will add new jobs. I hope that is true.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy consultant.

@llewellynking2

Llewellyn King: A reminder of kings and emperors to rise at the White House, to burden the taxpayers for decades

The East Wing of the White House being demolished on Oct. 21, 2025. A huge ballroom paid for by Trump campaign donors and other rich people will replace it. In return for? Thereafter, themass of taxpayers will cover the maintenance costs.

—Photo by Sizzlipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Donald Trump is building what will become one of the greatest snow-colored pachyderms in the history of the United States.

Some of the nation's biggest tycoons are going to pay to build this ballroom, which will look like the box that the rest of the White House came in — a statement often made about the Kennedy Center looking like the container that the adjacent Watergate complex came in.

Those favor-seeking tycoons won't be around to maintain the building as it stands mostly empty through the decades. Buildings that stand empty deteriorate rapidly. This piece of megalomania, expressed in stone, concrete and gold leaf, will be a burden to taxpayers.

Its ostensible purpose is for state dinners, where heads of state we as a nation want to flatter are dined. They should be called state ingratiation events.

When the president of the United States gives you a state dinner, you are exalted, whether it is haute cuisine in a gilded neoclassical building that looks like a 19th-Century railroad station or in a tent. The office of the president doesn't need gold leaf and vaulted ceilings to embellish it.

"Location, location, location," say the real-estate agents, and there's the rub. The White House is, by design, inaccessible.

I can say this with authority because for years I had a so-called White House hard pass and could gain entry quite easily. Even with it, my personal belongings and I had to pass through scanners at the visitor gates.

If you don't have a hard pass, you will have a hard time. You need an escort, and that must be arranged. Things lighten up a bit for events such as the Christmas parties. If you want to be there in time to have your picture taken shaking hands with the president, get there extra early.

The White House gates are a nightmare, and sometimes precleared names are lost mysteriously in the computer system. This happened to a reporter who worked for me who was invited to a press picnic held on the South Lawn during the Clinton administration. The poor fellow had to stand outside the gate like an untouchable while the rest of us got through.

Eventually, he got in. President Bill Clinton — who had an extraordinary ability to find a discomforted person in any situation and make them feel good — put his arm around the reporter in no time. When you have had difficulty getting into the White House, you mostly just feel rejected. The Secret Service makes a person waiting to be cleared for entry at the gates feel inferior or implies that they are up to no good.

My wife, Linda Gasparello, a fully accredited White House correspondent at the time, used her influence to get the crooner Vic Damone, who had an appointment, past the implacably suspicious gatekeepers. He was nearly in tears of frustration from the way he was treated.

The envisioned shimmering excess at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue won't lend itself to being used for charity events or non-White House galas. It will be just too difficult to get in.

Washington isn't short on big, fancy spaces. I believe that the biggest (besides armories and hangars) is the ballroom of the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. That room can seat over 2,700 and hold 4,600 for non-dinner events.

The Trump Ballroom would accommodate 1,000, we are told, presumably seated. So, it is too small for one kind of event and possibly too big for other events that might take place at the White House, if the attendees can get through the security barriers.

Washington isn't London or Paris. It isn't overstocked with grandiose ceremonial structures built by kings and emperors for their own aggrandizement. Instead, it has fun spaces that are pressed into service for formal affairs, such as the Spy Museum, the National Building Museum or the Air and Space Museum, in keeping with a nation that prizes its citizens over its leaders.

It seems to me that it is wholly appropriate for the United States to show national humbleness, as befits a country that threw off a king and his grandeur 250 years ago.

I have always thought that the tents put up for state dinners at the White House had a particularly American charm — a modest reproach to the world of dictators and fame-seekers, an unsaid rebuke to ostentation.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Our dichotomous America

One year after the 2016 election that delivered Donald Trump his first term, American Facebook users on the right and left shared very few common interests.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

We live in an age of dichotomy in America.

The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

We have more means of communication, but there is a pandemic of loneliness.

We have unprecedented access to information, but we seem to know less, from civics to the history of the country.

We are beginning to see artificial intelligence displacing white-collar workers in many sectors, but there is a crying shortage of skilled workers, including welders, electricians, pipe fitters and ironworkers.

If your skill involves your hands, you are safe for now.

New data centers, hotels and mixed-use structures, factories and power plants are being delayed because of worker shortages. But the government is expelling undocumented immigrants, hundreds of thousands who have skills.

Thoughts about dichotomy came to me when Adam Clayton Powell III and I were interviewing Hedrick Smith, a journalist in full: a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and editor, an Emmy Award-winning producer/correspondent and a bestselling author.

We were talking with Smith on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public affairs program on PBS for which I serve as executive producer and co-host.

The two dichotomies that struck me were Smith's explanation of the decline of the middle class as the richest few rise, and how Congress has drifted into operating more like the British Parliament with party-line votes than the body envisaged by The Founders.

Echoing Benjamin Disraeli, the great British prime minister who said in 1845 that Britain had become “two nations," rich and poor, Smith said: “Since 1980, a wedge has been driven. We have become two Americas economically."

On the chronic dysfunction in Congress, Smith said: “When I came to Washington in 1962, to work for The New York Times, budgets got passed routinely. Congress passed 13 appropriations bills for different parts of the government. It happened every year."

This routine congressional action happened because there were compromises, he said, noting, “There were 70 Republicans who voted for Medicare along with 170 Democrats. (There was) compromise on the national highway system, sending a man to the moon in competition with the Russians. Compromise on a whole slew of things was absolutely common."

Smith remembered those days in Washington of order, bipartisanship and division over policy, not party. There were Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans, and Congress divided that way, but not routinely by party line.

He said, “There were Gypsy Moth Republicans who voted with Democratic presidents and Boll Weevil Democrats who voted with Republican presidents."

In fact, Smith said, there wasn't a single party-line vote on any major issue in Congress from 1945 to 1993.

“The Founding Fathers would never have imagined that we would have what the British call ‘party government.' Our system is constructed to require compromise, while we now have a political system that is gelled in bipartisanship."

On the dichotomy between the rich and the poor, Smith said that in the period from World War II up until 1980, the American middle class was experiencing a rise in its standard of living roughly keeping up with what was happening to the rich.

But since 1980, he said, “The upper 1 percent, and even the top 10 percent, have been soaring and the rest of the country has fallen off the cliff."

This dichotomy, according to Smith, has had huge political consequences.

In 2016, he said, Donald Trump ran for president as an advocate of the working class against the establishment Republicans: “He had 15 Republican (contenders) who were pro-business; they were pro-suburban Republicans who were well-educated, well-off. Trump had run on the other side, trying to grab the people who were aggrieved and left out by globalization. But we forget that," he said.

Smith went on to say that Bernie Sanders, the Democratic presidential candidate in 2016, did the same thing: “He was a 70-year-old, white-haired socialist who came from Vermont, with its three electoral votes, but he ran against the establishment candidate, Hillary Clinton ... and he damn near took the nomination away from her."

Smith said that result showed “there was rebellion against the establishment."

That rebellion, in my mind, has resulted in a worsening separation between and within the parties. They aren't making compromises which, as in times past, would offer a way forward.

A final dichotomy: The United States is the richest country the world has ever seen, and the national debt has just reached $38 trillion dollars.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Fear floods America under Trump

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is enough fear to go around.

There is fear of the indescribable horror when the ICE men and women, their faces hidden by masks, grab a suspected illegal immigrant. Their grab could come at the person's home or place of work, while picking up a child from school or standing in the hallway of a courthouse.

That person knows fear as never before. That person's life, for practical purposes, may be over: loved ones left behind, hope shredded. He or she may be shipped to a place where they won't be able to survive.

Fear is there because, maybe decades ago, they sought a better life and voted for it with their feet.

There is no time to argue, no time to ask why, no time to say goodbye. No time to prove your innocence or your U.S. citizenship. It is raw fear — the fear that secret police have always used.

There is the fear of those who work in government — once one of the securest jobs in the country — that they will be fired because their legitimate work in another administration is an affront to this one.

This hammer has come down in the Department of Justice, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the Pentagon. The crime: supposedly being on the wrong side of history.

There is fear in the universities. Once a babel of free, even outrageous speech, they are cowed.

Mighty Harvard, one of the shiniest stars in the education firmament, is dulled, and other universities fear they will be next. Everywhere academics worry that what they say in their classrooms might be reported as inappropriate — their careers ended.

There is fear in the law firms. A new concept is at work: an advocate is somehow guilty because of whom they defended. This violates the whole underpinning of law and advocacy, dating back to Mesopotamia, ancient Greece and Rome, now asunder in the United States.

Media are afraid. Disney, CBS and The Washington Post have bent before the fear of retribution, the fear that other aspects of their business will pay the price for freedom of speech. Journalists fear the First Amendment is abridged and won't protect them.

There is fear, albeit of a lower order, across corporate America as it has become apparent that the government can reach deep down into almost any company, canceling contracts, withholding loan guarantees and, worse, ordering an “investigation." That is a punishment that costs untold dollars and shatters good names, even if no prosecution follows.

Elected officeholders have reason to feel fear. President Trump has suggested that Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson should be in jail. Is his compliant Department of Justice working on that? Fear is unleashed for the elected. Doing your job is no protection.

If you have expressed an opinion that could be judged as subversive, the state could come after you. Suppose you walk in a demonstration, exercising your constitutional right to assemble and petition? Suppose you wrote something on social media, so easily traced with AI, which is now out of step with the times? Satire? Opinion? News? Facts that are out of fashion? If you have posted, be afraid.

If you take a flight these days, the Transportation Security Administration will ask you to look into a camera. Then government has a fresh picture of you in its active system, ready for facial recognition software to identify you. It will ID you if you should be walking in a demonstration or just be near one. Your own picture, so easily captured by modern technology, can convict you.

What is the purpose of that picture? It has no bearing on the flight you are about to take. The same thing is true when you reenter the country from abroad. Smile for Big Brother.

Surveillance is a favored tool of the authoritarian state. I have seen it at work in Cuba, in apartheid South Africa and in the Soviet Union. Successive U.S. administrations have been quick to criticize the increasing use of technology for surveillance in China. No more.

Troops are being ordered into cities where the locals don't want them. They come under the promiscuous use of the Insurrection Act of 1807.

Does America fear insurrection? No, but there is fear of federal troops in our cities.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: AI could be apocalyptic for jobs

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The Big One is coming, and it isn't an earthquake in California or a hurricane in the Atlantic. It is the imminent upending of so many of the world's norms by artificial intelligence, for good and for ill.

Jobs are being swept away by AI not in the distant future, but right now. A recent Stanford University study found that entry-level jobs for workers between 22 and 25 years old have dropped by 13 percent since the widespread adoption of AI.

Another negative impact of AI: The data centers that support AI are replacing farmland at a rapid rate. The world is being overrun with huge concrete boxes, Brutalist in their size and visual impact.

Meta Platforms (of which Facebook is part) plans to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to build several massive AI data centers; the first called Prometheus and the second Hyperion.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in a post on his Threads social media platform: “We're building multiple more titan clusters as well. Just one of these covers a significant part of the footprint of Manhattan.”

Data centers are voracious in their consumption of electricity and are blamed for sending power bills soaring across the country.

But AI has had a positive impact on the quality of medicine, improving accuracy, consistency and efficacy, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Predictive medicine is on a roll: Alzheimer's Disease and some cancers, for example, can be predicted accurately. That raises the question: Do you want to know when you will lose your mind or get cancer?

Where AI is without downside is medical “exaptation.” That happens when a drug or therapy developed for one disease is found to be effective with another, opening up a field of possibilities.

AI also offers the chance of shortening clinical trials for new drugs from years to a few months. Side effects and downsides can be mapped instantly.

Life expectancy is predicted to increase substantially because of AI. Omar Hatamleh, an AI expert and author, told me, “A child born today can expect to live to 120.”

Likewise, predictive maintenance with AI is already useful in forecasting the failure of industrial plants, power station components and bridges.

Oh, and productivity will increase across the board where AI and AI agents — the AI tools developed for special purposes — are at work.

The trouble is AI will be doing the work that heretofore people have done.

Pick a field and speculate on the job losses there. This may be fun to do as a parlor game, but it is deeply distressing when you realize that it could happen in the very near future — such as in the next year.

Most are low-skilled white-collar jobs, such as those in call centers, or in medical offices checking insurance claims, or in an accounting firm doing bookkeeping. In short, if you are a paper pusher, you will be pushed out.

Look a little further — maybe 10 years — and Uber, which has invested heavily in autonomous vehicles, will have decided that they are ready for general deployment. Bye-bye Uber driver, hello driverless car.

Taxis and truck drivers might well be the next to get to their career-end destinations quicker than they expected.

By the way, autonomous vehicles ought to have fewer accidents than cars with drivers do, so the insurance industry will take a hit and lots of workers there will get the heave-ho. And collision repairs may be nearly outdated.

These aren't speculation; they are real possibilities in the near future. Yet the political world has been arguing about other things.

As far as I am aware, when the leadership of the U.S. military gathered at the Marine Corp Base Quantico in Virginia on Sept. 30 to get a pep talk on shaving, losing weight and gender superiority, they didn't hear about how AI is transforming war and what measures should be taken. Or whether there will be work for those who leave the military.

The Big One is coming, and the politicians are worrying about yesterday's issues. That is like worrying about your next guest list when an uninvited guest, a tsunami of historic proportions, is coming ashore.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Trump policies are threatening U.S. leadership of world science

Entrance to the MIT Museum, in Cambridge Mass. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, founded in 1861, has played a major role in advancing science and engineering.

S5A-0043 photo

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Pull up the drawbridge, flood the moat and drop the portcullis. That, it would seem, is the science and research policy of the United States circa 2025.

The problem with a siege policy is that eventually the inhabitants in the castle will starve.

Current actions across the board suggest that starvation may become the fate of American global scientific leadership. Leadership which has dazzled the world for more than a century. Leadership that has benefited not just Americans but all of humanity with inventions ranging from communications to transportation, to medicine, to entertainment.

An American president might have gone to the United Nations and said, “As we the people of America have given so much to the world, from disease suppression to the wonder of the Internet, we should expect understanding when we ask of you what is very little.”

This imaginary president might have added, “The United Nations is a body of diverse people, and we are a nation of diverse people.

“We have been a magnet for the talent of the world from the creation of this nation.

“We are also a sharing nation. We have shared with the world financially and technologically. Above all, we have shared our passion for democracy, our respect for the individual and his or her human rights.

“At the center of our ability to be munificent is our scientific muscle.”

This president might also have wanted to dwell on how immigrant talent has melded with native genius to propel and keep America at the zenith of human achievement -- and keep it there for so long, envied, admired and imitated.

He might have mentioned how a surge of immigrants from Hitler’s Germany and elsewhere in Europe gave us movie dominance that has lasted nearly 100 years. He might have highlighted the energy that immigrants bring with them; their striving is a powerful dynamic.

He might have said that striving has shaped the American ethos and was behind Romania-born Nikola Tesla, South Africa-born Elon Musk or India-born and China-born engineers who are propelling the United States leadership in artificial intelligence. The genius behind Nvidia? Taiwan-born Jensen Huang.

I have been reporting on AI for about a decade — well before ChatGPT exploded on the scene on Nov. 30, 2022. All I can tell you is wherever I have gone, from MIT to NASA, engineers from all over the world are all over the science of AI.

The story is simple: Talent will out, and talent will find its way to America.

At least that was the story. Now the Trump administration, with its determination to exclude the foreign-born -- to go after foreign students in U.S. universities and to make employers pay $100,000 for a new H-1B visa -- is to guarantee that talent will go somewhere else, maybe Britain, France, Germany or China and India. Where the talent goes, so goes the future.

So goes America’s dominant scientific leadership.

At a meeting at an AI startup in New York, all the participants were recent immigrants, and we fell to discussing why so much talent came to the United States. The collective answer was freedom, mobility and reverence for research.

That was a year ago. I doubt the answers would be as enthusiastic and volubly pro-American today.

The British Empire was built on technological dominance, from the marine chronometer to the rifled gun barrel to steam technology.

America’s global leadership has been built, along with its wealth, on technology, from Ford’s production line to DuPont’s chemicals.

Technology needs funding, talent and passion (the striving factor). We have led the world with those for decades. Now that is in the balance.

President Trump could make America even greater: beat cancer, go to Mars, and harness AI for human good.

Those would be a great start. To do it, fund research and attract talent. Keep the castle of America open.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international enerygy consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: The agony of statelessness

Stateless children at at the Schauenstein, Germany, displaced-persons camp in about 1946. There were millions of displaced and stateless people in Europe as World War II ended.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have only known one stateless person. You don't get a medal for it or wear a lapel pin.

The stateless are the hapless who live in the shadows, in fear.

They don't know where the next misadventure will come from: It could be deportation, imprisonment or an enslavement of the kind the late Johnny Prokov suffered as a shipboard stowaway for seven years.

His story ended well, but few do.

When I knew Johnny, he was a revered bartender at the National Press Club in Washington. By then, he had American citizenship, was married and lived a normal life.

It hadn't always been that way. He told me that he had come from Dalmatia, when that area was so poor people took their clothes to a specialist who would kill the lice in the seams with a little wooden mallet, which wouldn't damage the cloth.

To escape that extreme poverty, Prokov became a stowaway on a ship.

So began his seven-year odyssey of exploitation and fear of violence. The captains took advantage of the free labor and total servitude of the stowaways.

Eventually, Prokov jumped ship in Mexico. He made his way to the United States, where a life worth living was available.

I don't know the details of how he became a citizen, but he dreamed the American dream — and it came true for him.

An odd legacy of his years at sea was that Prokov had become a brilliant chess player. He would often have as many as a dozen chess games going along the bar in the National Press Club. He always won. He had had time to practice.

The United Nations says there are 4 million stateless people in the world, but that is a massive undercount. Many of those who are stateless are refugees and have no idea if they are entitled to claim citizenship of the countries they are desperate to escape from. Citizenship in Gaza?

Now the Trump administration wants to add to the number of stateless people by denying birthright citizenship to children born of illegal immigrants in the United States.

It wants to deny people — who are in all ways Americans — their constitutional right of citizenship. Their lives will be lived on a lower rung than their friends and contemporaries. They will be denied passports, maybe education, possibly medical care, and the ability to emigrate to any country that otherwise might have received them.

Instead, they will live their lives in the shadows, children of a lesser God, probably destined to have children of their own who might also be deemed noncitizens. They didn't choose the womb that bore them, nor did they sanction the actions of their parents.

The world is awash in refugees fleeing war, crime and violence, and environmental collapse. Those desperate people will seek refuge in countries which can't absorb them and will take strong actions to keep them out, as have the United States and, increasingly, countries in Europe.

There is a point, particularly in Europe, where the culture, including established religion, is threatened by different cultures and clashing religions.

But when it comes to children born in America to mothers who live in America, why mint a new class of stateless people, condemned to a second-class life here, or deport them to some country, such as Rwanda or Uganda, where its own people are already living in abject poverty?

All immigrants can't be accommodated, but the cruelty that now passes for policy is hurtful to those who have worked hard and dared to seek a better life for themselves and their children.

It is bad enough that millions of people are seeking somewhere to live and perchance a better life, due to war or crime or drought or political follies.

To extend the numbers by denying citizenship to the children of parents who live and work here isn't good policy. It is also unconstitutional.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the administration, it will add social instability of haunting proportions.

Children are proud of their native lands. What will the new second class be proud of — the home that denied them?

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Amidst immigration crisis, from special relationship to odd couple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Through two world wars, it has been the special relationship: the linkage between the United States and Britain. A linkage forged in a common language, a common culture, a common history, and a common aspiration to peace and prosperity.

The relationship, always strong, was especially burnished by the friendship of President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Now it looks as though the special relationship has morphed into the odd couple.

Britain, it can be argued, went off the rails in 2016 when, by a narrow majority, it voted to pull out of the European Union.

With a negative growth rate, and few prospects of an economic spurt, Britons can now ponder the high price of chauvinism and the vague comfort of untrammeled sovereignty. Americans could ponder that, too, in the decades ahead.

Will tariffs -- which have already driven China, Russia and India into a kind of who-needs-America bloc -- be the United States’ equivalent of Brexit? An economic idea which doesn’t work but has emotional appeal. An idea that is isolating, confining and antagonizing.

A common thread in the national dialogues is immigration.

Britain is swamped. It is dealing with an invasion of migrants that has changed and continues to change the country.

In 2023, according to the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics, 1.326 million migrants moved to Britain; last year, the number was 948,000. There has been a steady flow of migrants over the past 50 years, but it has increased dramatically due to wars around the globe.

Among European countries, Britain, to its cost, has had the best record for assimilating new arrivals. It is a migrant heaven, but that is changing with immigrants being blamed for a rash of domestic problems, from housing shortages to vastly increased crime.

In the 1960s, Britain had very little violent crime and street crime was slight. Now crime of all kinds -- especially using knives -- is rampant, and British cities rival those across America -- although crime seems to be declining in America, while it is rising in Britain.

Britain has a would-be Donald Trump: Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK party, which is immigrant-hostile and seeks to return Britain to the country it was before migrants started crossing the English Channel, often in small boats.

Farage has been feted by conservatives in Congress, where he has been railing against the draconian British hate-speech laws, which he sees as woke in overdrive.

Britain has been averaging 30 arrests a day for hate speech and related hate crimes, few of which result in convictions.

Two recent events highlight the severity of these laws. Lucy Connolly, the 42-year-old wife of a conservative local politician, took issue with the practice of housing immigrants in hotels; she said the hotels should be burned down. Connolly was sentenced to 31 months in jail. She has been released, after serving 40 percent of her sentence.

A very successful Irish comedy writer for British television, Graham Linehan, posted attacks on transgender women on X. On Sept. 1, after a flight from Arizona, he was met by five-armed policemen and arrested at London’s Heathrow Airport.

Britain’s hate laws, which are among the most severe in the world, run counter to a long tradition of free speech, dating back to the Magna Carta, in 1215. An attempt to get more social justice has resulted in less justice and abridged the right to speak out. A crisis in a country without a formal constitution.

On Sept. 17, President Trump is due to begin a state visit to Britain. Fireworks are expected. Trump’s British supporters, despite Farage and his hard-right party, are still few and public antipathy is strong.

Trump, for his part, will seek to make his visit a kind of triumphal event, gilded with overnight posts on Truth Social on how Britain should emulate him.

The British press will be ready with vituperative rebukes; hate speech be damned.

It is unlikely that the Labor government, whose membership is as diverse and divided as that of the Democratic Party, will find anything to call hate speech about attacks on Trump. A good dust-up will be enjoyed by all.

Isolated, the odd couple have each other.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Will AI launch a shadow government that can catch Trump, et al., trying to cook the books?

Read about a meeting of the minds at a summer workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956 that helped launch artificial intelligence as a discipline and gave it a name.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This Time It’s Different is the title of a book by Omar Hatamleh on the impact of artificial intelligence on everything.

By this Hatamleh, who is NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s chief artificial intelligence officer, means that we shouldn’t look to previous technological revolutions to understand the scope and the totality of the AI revolution. It is, he believes, bigger and more transformative than anything that has yet happened.

He says AI is exponential and human thinking is linear. I think that means we can’t get our minds around it.

Jeffrey Cole, director of the Center For the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, echoes Hatamleh.

Cole believes that AI will be as impactful as the printing press, the internet and COVID-19. He also believes 2027 will be a seminal year: a year in which AI will batter the workforce, particularly white-collar workers.

For journalists, AI presents two challenges: jobs lost to AI writing and editing, and the loss of truth. How can we identify AI-generated misinformation? The New York Times said simply: We can’t.

But I am more optimistic.

I have been reporting on AI since well before ChatGPT launched in November 2022. Eventually, I think AI will be able to control itself, to red flag its own excesses and those who are abusing it with fake information.

I base this rather outlandish conclusion on the idea that AI has a near-human dimension which it gets from absorbing all published human knowledge and that knowledge is full of discipline, morals and strictures. Surely, these are also absorbed in the neural networks.

I have tested this concept on AI savants across the spectrum for several years. They all had the same response: It is a great question.

Besides its trumpeted use in advancing medicine at warp speed, AI could become more useful in providing truth where it has been concealed by political skullduggery or phony research.

Consider the general apprehension that President Trump may order the Bureau of Labor Statistics to cook the books.

Well, aficionados in the world of national security and AI tell me that AI could easily scour all available data on employment, job vacancies and inflation and presto: reliable numbers. The key, USC’s Cole emphasizes, is inputting complete prompts.

In other words, AI could check the data put out by the government. Which leads to the possibility of a kind of AI shadow government, revealing falsehoods and correcting speculation.

If AI poses a huge possibility for misinformation, it also must have within it the ability to verify truth, to set the record straight, to be a gargantuan fact checker.

A truth central for the government, immune to insults, out of the reach of the FBI, ICE or the Justice Department —and, above all, a truth-speaking force that won’t be primaried.

The idea of shadow government isn’t confined to what might be done by AI, but is already taking shape where DOGEing has left missions shattered, people distraught and sometimes an agency unable to perform. So, networks of resolute civil servants inside and outside government are working to preserve data, hide critical discoveries and to keep vital research alive. This kind of shadow activity is taking place at the Agriculture, Commerce, Energy and Defense departments, the National Institutes of Health and those who interface with them in the research community.

In the wider world, job loss to AI, or if you want to be optimistic, job adjustment has already begun. It will accelerate but can be absorbed once we recognize the need to reshape the workforce. Is it time to pick a new career or at least think about it?

The political class, all of it, is out to lunch. Instead of wrangling about social issues, it should be looking to the future, a future which has a new force, much as automation was a force to be accommodated, this revolution can’t be legislated or regulated into submission, but it can be managed and prepared for. Like all great changes, it is redolent with possibility and fear.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

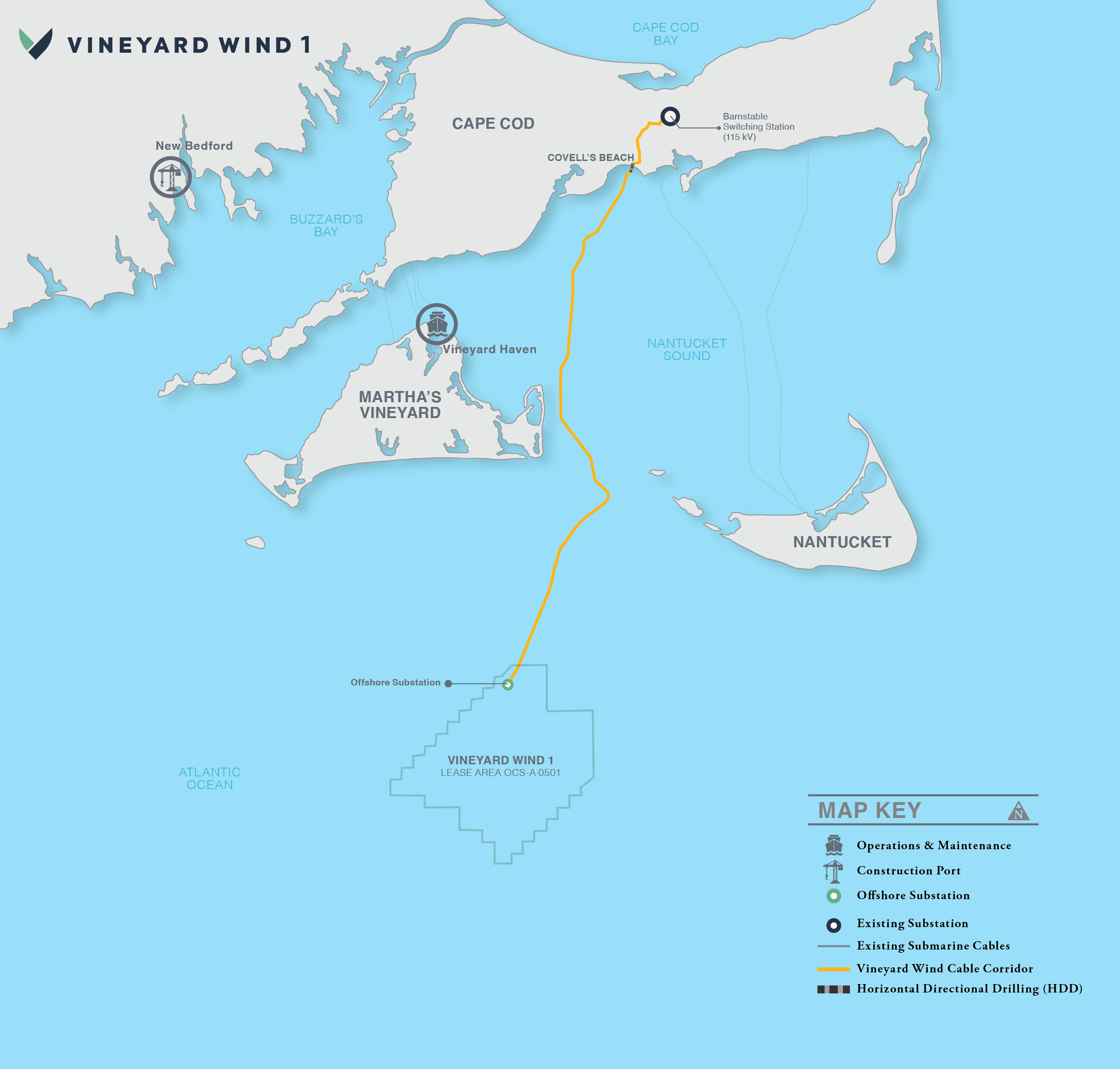

Llewellyn King: Sorry, Trump, solar and wind power will keep growing in U.S.; utilities urgently need them

BlueWave's 5.74 MW DC, 4 MW community solar project in Orrington, Maine. It’s one of the largest such facilities in New England.

—Courtesy: BlueWave

The small wind farm off Block Island.

Vineyard Wind 1 is partly operating.

This commentary was originally published in Forbes.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Trump reiterated his hostility to wind generation when he recently arrived in Scotland for what was ostensibly a private visit. “Stop the windmills,” he said.

But the world isn’t stopping its windmill development and neither is the United States, although it has become more difficult and has put U.S. electric utilities in an awkward position: It is a love that dare not speak its name, one might say.

Utilities love that wind and solar can provide inexpensive electricity, offsetting the high expense of battery storage.

It is believed that Trump’s well-documented animus to wind turbines is rooted in his golf resort in Balmedie, near Aberdeen, Scotland. In 2013, Trump attempted to prevent the construction of a small offshore wind farm — just 11 turbines — roughly 2.2 miles from his Trump International Golf Links, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He argued that the wind farm would spoil views from his golf course and hurt tourism in the area.

Trump seemingly didn’t just take against the local authorities, but against wind in general and offshore wind in particular.

Yet fair winds are blowing in the world for renewables.

Francesco La Camera, director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency, an official United Nations observer, told me that in 2024, an astounding 92 percent of new global generation was from wind and solar, with solar leading wind in new generation. We spoke recently when La Camera was in New York.

My informal survey of U.S. utilities reveals they are pleased with the Trump administration’s efforts to simplify licensing and its push to natural gas, but they are also keen advocates of wind and solar.

Simply, wind is cheap and as battery storage improves, so does its usefulness. Likewise, solar. However, without the tax advantages that were in President Joe Biden’s signature climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, the numbers will change, but not enough to rule out renewables, the utilities tell me.

China leads the world in installed wind capacity of 561 gigawatts, followed by the United States with less than half that at 154 GW. The same goes for solar installations: China had 887 GW of solar capacity in 2024 and the United States had 239 GW.

China is also the largest manufacturer of electric vehicles. This gives it market advantage globally and environmental bragging rights, even though it is still building coal-fired plants.

While utilities applaud Trump’s easing of restrictions, which might speed the use of fossil fuels, they aren’t enthusiastic about installing new coal plants or encouraging new coal mines to open. Both, they believe, would become stranded assets.

Utilities and their trade associations have been slow to criticize the administration’s hostility to wind and solar, but they have been publicly cheering gas turbines.

However, gas isn’t an immediate solution to the urgent need for more power: There is a global shortage of gas turbines with waiting lists of five years and longer. So no matter how favorably utilities look on gas, new turbines, unless they are already on hand or have set delivery dates, may not arrive for many years.

Another problem for utilities is those states that have scheduled phasing out fossil fuels in a given number of years. That issue – a clash between federal policy and state law — hasn’t been settled.

In this environment, utilities are either biding their time or cautiously seeking alternatives.

For example, facing a virtual ban on new offshore wind farms, veteran journalist Robert Whitcomb wrote in his New England Diary that the New England utilities are looking to wind power from Canada, delivered by undersea cable. Whitcomb co-wrote (with Wendy Williams) a book, Cape Wind: Money, Celebrity, Energy, Class, Politics and the Battle for Our Energy Future, about offshore wind, published in 2007.

New England is starved of gas as there isn’t enough pipeline capacity to bring in more, so even if gas turbines were readily available, they wouldn’t be an option. New pipelines take financing, licensing in many jurisdictions, and face public hostility.

Emily Fisher, a former general counsel for the Edison Electric Institute, told me, “Five years is just a blink of an eye in utility planning.”

On July 7, Trump signed an executive order which states: “For too long the Federal Government has forced American taxpayers to subsidize expensive and unreliable sources like wind and solar.

“The proliferation of these projects displaces affordable, reliable, dispatchable domestic energy resources, compromises our electric grid, and denigrates the beauty of our Nation’s natural landscape.”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration puts electricity consumption growth at 2 percent nationwide. In parts of the nation, as in some Texas cities, it is 3 percent.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island

Llewellyn King: A way forward for PBS from genteel poverty

Studios of WGBH-TV, on Guest Street in Boston (with “digital mural" LED screen). The now PBS affiliate, which opened in 1955, is one of the oldest and best endowed public-television stations, and the site of much programing used by PBS.

The station's call letters refer to Great Blue Hill, in Milton, the highest point in the inner Greater Boston area, at 635 feet. The top of the hill served as the original location of WGBH-TV's transmitter facility. The transmitter for WGBH radio, a major NPR affiliate, continues to operate to this day.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Over the years, I have often been critical of the Public Broadcasting Service. That in spite of the fact that for 28 years, I have produced and hosted a program, White House Chronicle, which is carried by many PBS stations.

It is an independent program for which I find all the funding and decide its direction, content and staffing.

My argument with PBS — brought to mind by the administration’s canceling of $1.1 billion in funding for it and National Public Radio — is that it is too cautious, that it is consciously or by default lagging rather than leading.

Television needs creativity, change and excitement. Old programs, carefully curated travel, and cooking shows don’t really don’t cut it. News and public-affairs shows are not enough. Cable does them 24/7.

My co-host on White House Chronicle, Adam Clayton Powell III, a savant of public broadcasting, having held executive positions at NPR and PBS, assures us that they aren’t going away, although some stations will fail.

I believe that PBS has often been too careful because of the money, which has been dribbled out by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Some conservatives have been after PBS since its launch.

It is reasonable to look to the British Broadcasting Corp. when discussing PBS because the BBC is the source of so much of the programming that is carried by PBS — although not all the British programming is from the BBC. Two of the most successful imports were from the U.K. — Upstairs, Downstairs, which aired in the 1970s, and, more recently, Downton Abbey — were developed by British commercial television, not by the BBC.

Even so, the BBC is a force that has played a major role in shaping state broadcasters in many countries. At its best, it is formidable in news, in drama and in creativity. It is also said to be left-of-center and woke. Both of these are things PBS is accused of, but I have never found bias in the news products. What I have found is a kind of genteel poverty.

I once asked the head of a major PBS station why it didn’t do more original American drama. “It would cost too much,” was the response in a flash. Yet, there are local theater companies aplenty who would love to craft something for PBS if they were invited.

Sometimes the idea is more important than the money. Get that right, and PBS will have something it can sell around the world. It should be an on-ramp for talent.

Maybe, stirred by its newly induced poverty, PBS can lead the television world into a new business paradigm.

First, of course, take advertising and don’t be coy about it, as Masterpiece Theater is about Viking cruises. Take the advertising.

Second, see what is happening across the television firmament, where more TV is now viewed on YouTube than on TV sets. This happens at a time of the viewer’s choosing. PBS needs to jump on this and create a pay-per-view paradigm so that when it has a big show, as it did with Ken Burns’ Civil War years ago, it can prosper, as well as selling the show around the globe.

PBS is a confederation of stations, each one independent but tethered to PBS in Washington, which provides what is known as the hard feed. These are programs pre-approved for central distribution by PBS. Independent producers aren’t acknowledged on this, nor do they get listed as being PBS programs.

I remember how I had heard that WHUT, Howard University’s television station, was open to new programs. So I took a pilot over to WHUT. One young woman said “yes” and a program was born.

PBS needs to open its doors to new talent, new shows and uses of new technologies. Leading the pack in broadcasting innovation would be the best revenge. New money will follow.

NPR is a different story. Its product is successful. But it needs to be open to new funding, including much better acknowledged corporate funding. If Google or some other cash-laden entity wants to underwrite a day of broadcasting, let it. Don’t give it the editor’s chair, just a seat in accounting.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

xxx

Llewellyn King: The joy of friendship; a very dark Fourth; ‘customer service’ oxymoron; AI in medicine