Liz Szabo: Looking at the Interplay of Omicron, reinfections and long COVID

“I suspect there will be millions of people who acquire long COVID after Omicron infection.”

— Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at Yale University.

The latest COVID-19 surge, caused by a shifting mix of quickly evolving omicron subvariants, appears to be waning, with cases and hospitalizations beginning to fall.

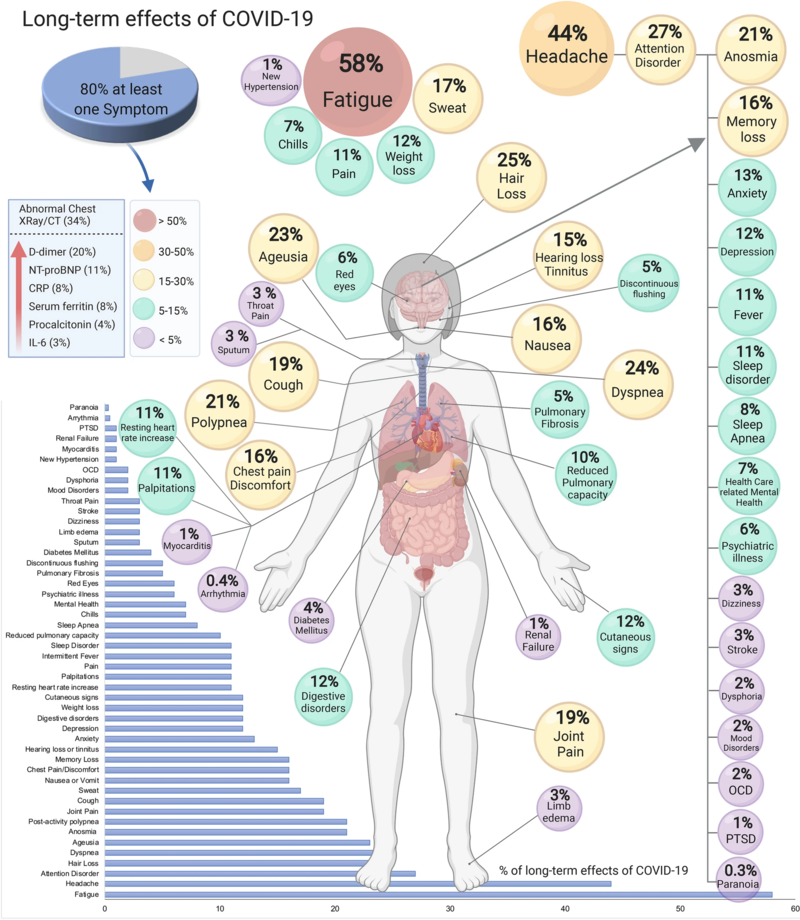

Like past COVID waves, this one will leave a lingering imprint in the form of long COVID, an ill-defined catchall term for a set of symptoms that can include debilitating fatigue, difficulty breathing, chest pain, and brain fog.

Although omicron infections are proving milder overall than those caused by last summer’s Delta variant, omicron has also proved capable of triggering long-term symptoms and organ damage. But whether omicron causes long covid symptoms as often — and as severe — as previous variants is a matter of heated study.

Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, is among the researchers who say the far greater number of Omicron infections compared with earlier variants signals the need to prepare for a significant boost in people with long covid. The U.S. has recorded nearly 38 million COVID infections so far this year, as Omicron has blanketed the nation. That’s about 40 percent of all infections reported since the start of the pandemic, according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Research Center.

Long COVID “is a parallel pandemic that most people aren’t even thinking about,” said Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at Yale University. “I suspect there will be millions of people who acquire long COVID after Omicron infection.”

Scientists have just begun to compare variants head to head, with varying results. While one recent study in The Lancet suggests that omicron is less likely to cause long COVID, another found the same rate of neurological problems after Omicron and Delta infections.

Estimates of the proportion of patients affected by long covid also vary, from 4 percent to 5 percent in triple-vaccinated adults to as many as 50 percent among the unvaccinated, based on differences in the populations studied. One reason for that broad range is that long COVID has been defined in widely varying ways in different studies, ranging from self-reported fogginess for a few months after infection to a dangerously impaired inability to regulate pulse and blood pressure that may last years.

Even at the low end of those estimates, the sheer number of omicron infections this year would swell long-covid caseloads. “That’s exactly what we did find in the U.K.,” said Claire Steves, a professor of aging and health at King’s College in London and author of the Lancet study, which found patients have been 24 to 50 percent less likely to develop long COVID during the Omicron wave than during the delta wave. “Even though the risk of long COVID is lower, because so many people have caught Omicron, the absolute numbers with long covid went up,” Steves said.

A recent study analyzing a patient database from the Veterans Health Administration found that reinfections dramatically increased the risk of serious health issues, even in people with mild symptoms. The study of more than 5.4 million V.A. patients, including more than 560,000 women, found that people reinfected with covid were twice as likely to die or have a heart attack as people infected only once. And they were far more likely to experience health problems of all kinds as of six months later, including trouble with their lungs, kidneys, and digestive system.

“We’re not saying a second infection is going to feel worse; we’re saying it adds to your risk,” said Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and education service at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

Researchers say the study, published online but not yet peer-reviewed, should be interpreted with caution. Some noted that VA patients have unique characteristics, and tend to be older men with high rates of chronic conditions that increase the risks for long covid. They warned that the study’s findings cannot be extrapolated to the general population, which is younger and healthier overall.

“We need to validate these findings with other studies,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation. Still, he added, the V.A. study has some “disturbing implications.”

With an estimated 82 percent of Americans having been infected at least once with the coronavirus as of mid-July, most new cases now are reinfections, said Justin Lessler, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Of course, people’s risk of reinfection depends not just on their immune system, but also on the precautions they’re taking, such as masking, getting booster shots, and avoiding crowds.

After her second COVID-19 infection, Tee Hundley, a Jersey City, N.J., \ salon owner, says her lungs seemed damaged: “I felt like I was breathing through a straw.” More than a year later, the tightness in her chest remains. “I feel like that’s something that will always be left over,” Hundley says. “You may not feel terrible, but inside of your body there is a war going on.”

After her second infection, she returned to work as a cosmetologist at her salon but struggled with illness and shortness of breath for the next eight months, often feeling like she was “breathing through a straw.”

She was exhausted, and sometimes slow to find her words. While waxing a client’s eyebrows, “I would literally forget which eyebrow I was waxing,” Hundley said. “My brain was so slow.”

When she got a breakthrough infection in July, her symptoms were short-lived and milder: cough, runny nose, and fatigue. But the tightness in her chest remains.

“I feel like that’s something that will always be left over,” said Hundley, who warns friends with covid not to overexert. “You may not feel terrible, but inside of your body there is a war going on.”

Although each Omicron subvariant has different mutations, they’re similar enough that people infected with one, such as BA.2, have relatively good protection against newer versions of omicron, such as BA.5. People sickened by earlier variants are far more vulnerable to BA.5.

Several studies have found that vaccination reduces the risk of long COVID. But the measure of that protection varies by study, from as little as a 15 percent reduction in risk to a more than 50 percent decrease. A study published in July found the risk of long COVID dropped with each dose people received.

For now, the only surefire way to prevent long covid is to avoid getting sick. That’s no easy task as the virus mutates and Americans have largely stopped masking in public places. Current vaccines are great at preventing severe illness but do not prevent the virus from jumping from one person to the next. Scientists are working on next-generation vaccines — “variant-proof” shots that would work on any version of the virus, as well as nasal sprays that might actually prevent spread. If they succeed, that could dramatically curb new cases of long COVIDF.

“We need vaccines that reduce transmission,” Al-Aly said. “We need them yesterday.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News correspondent.

Llewellyn King: ‘Long COVID’s’ baffling sister

CFS vitim demonstrates for more research

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Long COVID’’ is the condition wherein people continue to experience symptoms for longer than usual after initially contracting COVID-19. Those symptoms are similar to the ones of another long-haul disease, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, often called Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

For a decade, in broadcasts and newspaper columns, I have been detailing the agony of those who suffer from ME/CFS. My word hopper isn’t filled with enough words to describe the abiding awfulness of this disease.

There are many sufferers, but how ME/CFS is contracted isn’t well understood. Over the years, research has been patchy. However, investigation at the National Institutes of Health has picked up and the disease now has measurable funding -- and it is taken seriously in a way it never was earlier. In fact, it has been identified since 1955, when the Royal Free Hospital, in London, had a major outbreak. The disease had certainly been around much longer.

In the mid-1980’s, there were two big cluster outbreaks in the United States -- one at Incline Village, on Lake Tahoe in Nevada, and the other in Lyndonville in northern New York. These led the Centers for Disease Control to name the disease “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.”

The difficulty with ME/CFS is there are no biological markers. You can’t pop round to your local doctor and leave some blood and urine and, bingo! Bodily fluids yield no clues. That is why Harvard Medical School researcher Michael VanElzakker says the answer must lie in tissue.

ME/CFS patients suffer from exercise, noise and light intolerance, unrefreshing sleep, aching joints, brain fog and a variety of other awful symptoms. Many are bedridden for days, weeks, months and years.

In California, I visited a young man who had to leave college and was bedridden at his parents’ home. He couldn’t bear to be touched and communicated through sensors attached to his fingers.

In Maryland, I visited a teenage girl at her parents’ home. She had to wear sunglasses indoors and had to be propped up in a wheelchair during the brief time she could get out of bed each day.

In Rhode Island, I visited a young woman, who had a thriving career and social life in Texas, but now keeps company with her dogs at her parents’ home because she isn’t well enough to go out.

A friend in New York City weighs whether to go out to dinner (pre-pandemic) knowing that the exertion may cost her two days in bed.

I know a young man in Atlanta who can work, but he must take a cocktail of 20 pills to deal with his day.

Some ME/CFS sufferers get somewhat better. The instances of cure are few; of suicide, many.

Onset is often after exercise, and the first indications can be flu-like. Gradually, the horror of permanent, painful, lonely separation from the rest of the world dawns. Those without money or family support are in the most perilous condition.

Private groups -- among them the Open Medicine Foundation, the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, and ME Action -- have worked tirelessly to raise money and stimulate research. The debt owned them for their caring is immense. This has allowed dedicated researchers from Boston to Miami and from Los Angeles to Ontario to stay on the job when the government has been missing. Compared to other diseases, research on ME/CFS has been hugely underfunded.

Oved Amitay, chief executive officer of the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, says Long COVID gives researchers an opportunity to track the condition from onset and, importantly, to study its impact on the immune system – known to be compromised in ME/CFS. He is excited.

In December, Congress provided $1.5 billion in funding over four years for the NIH to support research into Long COVID. The ME/CFS research community is glad and somewhat anxious. I’m glad that there will be more money for research, which will spill into ME/CFS, and worried that years of endeavor, hard lessons learned and slow but hopeful progress will be washed away in a political roadshow full of flash.

Ever since I began following ME/CFS, people have stressed to me that more money is essential. But so are talented individuals and ideas.

Long COVID needs carefully thought-out proposals. If it is, in fact, a form of ME/CFS, it is a long sentence for innocent victims. I have received many emails from ME/CFS patients who pray nightly not to wake up in the morning. The disease is that awful.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

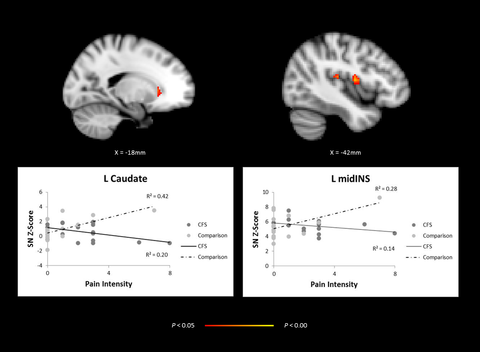

Brain imagining, comparing adolescents with CFS and healthy controls showing abnormal network activity in regions of the brain