Andrew Warburton: Where pixilated' came from

English pixies playing on the skeleton of a cow.

— John D. Batten. c.1894

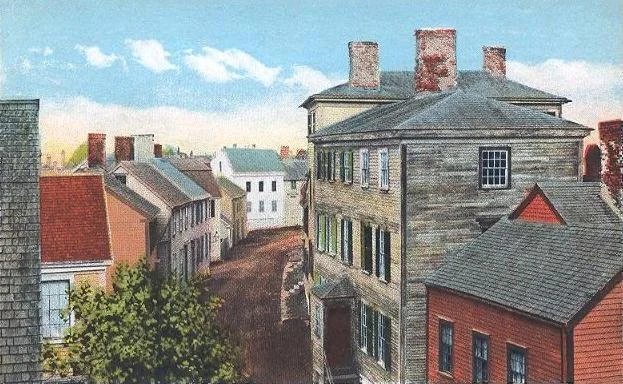

Front Street in Marblehead around the turn of the 20th Century.

1916 photo

Text excerpted from The New England Historical Society Web site

“When I say that the town of Marblehead on Massachusetts’s North Shore is unlike other coastal Massachusetts towns, I’m not simply referring to the fact that it’s teeming with fairies and pixies (which it is). Isolated from the state’s highway system on a remote peninsula, the town has always boasted a most unorthodox history.

“Think of it as the black sheep of Colonial New England. Whereas Puritans founded the surrounding settlements of Salem, Peabody, and Danvers to be pure and godly communities, Marblehead’s beginnings were more down to earth. According to historians Priscilla Sawyer Lord and Virginia Clegg Gamage, ‘irreligious settlers’ and ‘adventurous fishermen’ founded the town to escape the harsh dictates of Puritanism while making a living catching fish. In about 1629, these humble but industrious early settlers headed south east to a peninsula where the Naumkeag Tribe lived. They coexisted peacefully with the tribe while establishing the sleepy fishing village we know today.

“Over the next few hundred years, Marblehead saw an influx of fairy-acquainted immigrants from Scotland and the fishing regions of South West England: Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, and Somerset. According to the historian Samuel Roads, immigration from England’s South West accounted for what he called Marblehead’s ‘idiomatic peculiarities….’’’

Wave action at Rough Point

The Rough Point mansion from Newport’s Cliff Walk.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s nice when artists and others use New England’s innumerable beautiful outdoor spaces for exhibitions.

Thus it is with artist Melissa McGill’s coming show “In the Waves’’ at Newport’s Rough Point (which we used to call Rough Trade), the estate of late and deeply eccentric, indeed creepy (but philanthropic!) billionairess Doris Duke.

Ms. McGill has put out a call for young people to participate in the show, set for next month and meant to focus attention on global warming-caused sea-level rise and other man-caused environmental issues. Dodie Kazanjian, the founder of Art & Newport, is the curator of the exhibition.

This spectacle involves Ms. McGill painting waves on fabric made out of recycled plastic pulled from the ocean; plastic pollution has become a huge menace to sea life. The young people participating in the spectacle will use handles at the ends of long fabric strips to create motion to mimic that of waves.=

“I’m painting the waves in a very expressive way, with the different colors that reference the ocean at Rough Point,” Ms. McGill told the Newport Daily News’s Sean Flynn, in a fun article. “I have done studies and research so they really evoke the ocean there.” (Does the ocean at Rough Point really look that much different than the ocean anywhere?)=

For more information, please hit this link.

xxx

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 29, 2012

xxx

As the seas rise, more and more people will have to move back from the shore and abandon their homes on land that’s increasingly vulnerable to flooding. That land will be left as a buffer to mitigate damage from storms. How much of it can be turned into public open space, as parks, bringing something good from the situation?

By the way, although it was published back in 1999, Cornelia Dean’s prescient book Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s Beaches, remains a dramatic, prescriptive (and often alarming) guide to the issues around rising seas and coastal development. Ms. Dean, the former New York Times science editor, continues to study the not-very-slow-motion coastal crisis.

Karen Gross: Role-modeling by adults too often lacking in COVID-19 crisis

The Rev. John Jenkins, the president of the University of Notre Dame. Did he not wear a mask at a reception in order to suck up to Donald Trump?

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Sadly, the number of COVID-19 cases across the globe is rising. And while vaccines are in the offing, we may have many weeks between now and their availability, time in which more individuals can become infected and too many will die. In absolute terms, the numbers are staggering in the U.S. and around the world.

It is against this background that we should be concerned about super-spreader events. One category of such events includes college and high school students gathering and partying in ways that violate the COVID-19 protective measures (mask wearing, social distancing, avoiding large indoor get-togethers). Some of these problematic events occur off campus, others occur on campus. Wherever they happen, they have produced varying outcomes: quarantines; stoppage of athletic events; elimination of on-campus in-person learning (for a short or long period); changes in scheduling to eradicate vacations or campus departures; and students contracting COVID.

It is easy to blame students (whether in college or high school) and parents (in the context of high schoolers and even some college students who are now at home taking online classes). Can you hear adults within families and educational institutions saying: “How stupid can these young people be? They aren’t complying with the three simple rules.”

But the failure of compliance among young people must be contextualized. We are not living in “normal” times and behaviors need to be understood in light of the impact of the pandemic constraints as well as the age of students and their developmental stage.

Lack of physical connection, risk-taking, brain development

Start with this obvious observation: The wearing of masks, social distancing and school closures have left many young people without quality means of connecting. As much as they can use technology and we are certainly doing that (Zoom fatigue is a known phenomenon, as is online oversharing), there is something that youth are missing: real, hands-on human engagement. They are missing contact; they are missing touch. They are without smiles and hugs and physicality.

The absence of physical contact for an extended period (and what still seems like an indefinite period) is difficult and frustrating for young people. It makes them want to rebel against the constraints and ignore the accompanying risks that often are known to them. In short, students disobey COVID-19 rules because they have real needs for in-person connectivity that are unmet.

Brain science supports this conclusion: Most young people cannot fully control their behavior on their own and they discard the COVID-19 rules because of the stage of their brain development. Risk-taking is common among young people; it goes hand and hand with their psychosocial development. We know that young people underestimate risk: think about fast cars and drunk driving, texting while driving and physical challenges that seem likely to cause serious physical injury. Also, we know that quality judgment and decision-making do not occur until the mid to late 20s. (There are also upsides to this stage of development but that’s the subject of another article.)

Our expectation of strict compliance misses the biological reality of why students are disobeying. The parts of their brain that manage and measure risks are not fully developed. Youth are not trying to be disobedient (well, some are as a form of rebellion that is also age-appropriate). Many simply are not able to make quality decisions—at least not without adult intervention, and therein lie some answers as to what we can do to move toward greater compliance.

Two concrete examples

Before turning to solutions, let’s look at two actual scenarios that inform a pathway forward.

In late October, more than 20 high schoolers attended a party at a private home in Marblehead, Mass. Not only was there an absence of mask wearing, there was an absence of social distancing and there was shared drinking out of cups. The police were called. The students scattered. No one was prosecuted. The superintendent in a remarkably astute letter recognized student needs to connect, but then closed the high school as a precaution and decried that they can and must do better.

A few months earlier, Marist College, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., suspended some students for participating in off-campus parties and later, when the non-compliance continued, had to shut down the campus physically. Before moving to online learning, the college president was quoted as saying: “Please don’t be a knucklehead who disregards the safety of others and puts our ability to remain on campus at risk.”

Pathways forward

We know that student risky behavior can be modified, and there are a variety of strategies that enable change. The problem is that we have not deployed them in the context of this pandemic for reasons that aren’t at all clear to me.

We would be wise to spend more time recognizing the psychological reasons for student behavior and, based on that science, create new strategies that mitigate the reasons noted above for non-compliance. And since the stage of student development also opens the door to creativity, why not use creativity as part of the solution?

Consider these approaches: Social-norming campaigns can show compliance or willingness to comply by many students to norms despite peer perceptions. Detailed discussions with students can lead to an understanding of the risks (based on science) to others and themselves with concrete examples and data points. Youth empathy engines can be activated such that students are engaged in doing activities that help others in their communities. These can be conducted by parents and educators alike. Consider a version of this “rock” project in Texas. Students could all get and paint rocks and then they and other students can place the rocks around school buildings or a college campus.

For the record, let’s eliminate one approach: student punishment and suspension as the first line of defense. We should be punishing when there is intent. Absent intent, we should not rush into suspending students. Yes, based on parties, we need to quarantine; yes, based on parties, we need to shut down campus residential life or in-person learning for a period of time. But calling people “knuckleheads” is not helpful.

Instead, let’s think about preemptive things that could be done to prevent the non-compliant risky behavior. We can do better, as the superintendent suggested, but we need to get ahead of the problem and not be reactive to it.

Role models

From my perspective, perhaps one of the best strategies for enabling students to shift behavioral patterns and avoid risky and unwise behavior is role modeling. We know that role modeling is critically important to youth. And role models can come from a variety of locations: family, older friends and peers, educators (including administrators and coaches), religious figures and community leaders. We also know that role models can be individuals whom students do not know personally: politicians, actors, athletes.

We know, too, that an antidote to trauma is a non-familial figure who knows you and genuinely cares about your well-being and believes in you. And we know that positive role models can and do counteract negative childhood and adult experiences. Our adults need to step it up—engage with one another and their children and peers in new ways.

Despite these truths, we aren’t doing a good job of role modeling locally or nationally. Consider the absence of good role modeling in the two concrete examples given earlier involving Marblehead and Marist and similar communities, schools and colleges.

With respect to Marblehead and similar communities where parties have occurred, I would ask (in a non-accusatory way): Where were the parents who lived in the home where the party was held? Were they home? Were they aware of the party in advance? Did they buy the items for the party? Where were the parents of the other students who attended the party? Did they know where their children were going that evening? What had the parents done in anticipation of the needs of their children to plan events that would be safe? What had the high school done in advance to recognize the need for students to engage but to construct initiatives that were safe for each student and the collective of students?

With respect to Marist and similar colleges, I would ask (again, in a non-accusatory way): Where were the student life personnel? Were they aware of particular off-campus sites that might present risks? What did they do in advance to provide for the engagement needs of students in safe ways? What messaging was coming from the administration in advance? And was the reference to the students as knuckleheads wise? By way of contrast, the superintendent in Marblehead overtly recognized the student need to engage in person in these difficult times, although for safety reasons, he closed in-person learning.

For me, Lesson One is that the institutions (both high school and postsecondary) and parents need to anticipate what activities could have meet student needs. And they should involve students in planning these events. There are a myriad of possibilities: art-installation projects; distant dancing; car get-togethers (remember “car hops?) with limited numbers in cars where students listen to live music or watch a movie together? What about wrapping all the trees in crepe paper to create a “Christo-esque” artwork and even, teaching about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s amazing and startling work involving wrapping buildings and bridges and parks?

We can be creative in seeing what the needs are and then developing approaches that meet the needs.

Lesson Two is that the parents (of the party home) and the parents of other teenagers were not (it appears) actively aware of their own child’s behavior. Had they been, I think one can rightly ask whether they would have intervened. And we can rightly ask whether they themselves, in their engagement with others, were role modeling the needed protective behavior (masks, social distancing and outdoor events). Or perhaps they did not believe in the science and thus were noncompliant.

At the college level, I’d suggest there were staff who could have guessed where problems off-campus were likely, especially if they knew their students and had their ears to the ground. Even if this was not their role before and seems interventionist or paternalistic (maternalistic), that non-interference calculus has changed when there are abundant and growing health risks not just to students but to communities. Stated differently, why did staff not act on what they learned, knew and anticipated?

Both examples showcase the absence of role modeling by adults in terms of actual behavior and anticipatory thinking.

Negative role modeling is way too common right now

Apart from role modeling by parents and educators whom students know, we have had far too many examples of failed role modeling in ways that have received national attention. And, make no mistake about this, students are well aware when public figures fail to comply with the COVID mandates and rightly ask: If they can flaunt the rules, why can’t I?

Here are several well-known examples (and I am avoiding the obvious one of our current president) that demonstrate what students are seeing in the media day-in and day-out.

Start with the Dodgers Justin Turner’s behavior following his team winning the World Series. I get the excitement but having just tested positive, he went out onto the field maskless for at least some of the time. What message does that send to young people? When you win, the rules don’t apply even though the coach was among people who were immune-compromised? And then the player went unsanctioned by Major League Baseball as if the incident should just be forgotten as a lapse in a moment of glory and because the player issued an apology.

Turn then to Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, a state struggling with COVID outbreaks (among other disasters). It turns out that he attended a birthday party with more than 10 unrelated family members at an elite restaurant in Napa and wasn’t wearing a mask apparently. Top doctors attended, too. All of this was directly in contradiction to the mandates he was issuing to his constituencies.

But perhaps the most offensive examples come from college presidents. Think about it. If our educational leaders, who have a bully pulpit and are preaching compliance to their institutions, don’t comply, why would their students or students on other campuses? A prime example is Notre Dame’s president, the Rev. John Jenkins. He attended a ceremony in honor of the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. To be sure, for his institution, this was a big deal as the nominee was a professor at Notre Dame’s Law School. But please, no mask? No social distancing? Was he afraid that the president (of the U.S) would see a mask as a sign of disrespect? The photographs of the non-compliance are chilling.

Students were rightfully angry as were faculty. An apology isn’t enough in the context of the virus; words don’t stop disease spread, especially when you are so forcefully asking for campus compliance with COVID protections. And Father Jenkins got COVID.

Lesson Three is obvious: Hypocrisy doesn’t fly in the COVID-19 world. Public high-profile leaders need to role model compliance all the time; their messaging is seen and heard and it matters. Negative role modeling is catching.

Now what?

The contents of this article and the examples given and lessons proffered boil down to this: We need to ramp up positive role modeling. Role modeling isn’t a part-time activity. It is a full-time obligation.

To that end, parents and educators: 1) need to come up with strategies in advance that recognize that young people need ways to engage safely; 2) must involve students in the planning of these activities that are COVID-safe; 3) need to question where students are and anticipate their behavior by offering alternatives; 4) need to talk more to students about risks and about solutions and about feelings and double standards; and 5) shouldn’t make punishment the best solution as it doesn’t work; instead, provide alternatives.

These aren’t impossible solutions. They are doable if we focus on them. And we should, for the well-being of our young people, our families and our communities.

Karen Gross is former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape. Her book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press.

Huxtable: Shedding clothes and tensions; 'not a perfect thing anywhere'

At Old Orchard Beach, in southern Maine

“Summer is the time when one sheds one’s tensions with one’s clothes, and the right kind of day is jeweled balm for the battered spirit. A few of those days and you can become drunk with the belief that all’s right with the world.’’

— Ada Louise Huxtable (1921-2013), famed architectural critic, on vacationing in New England, in the September 1977 New York Times

Although the New York City-born and -bred Huxtable was most associated with that city, she spent much of her time in Marblehead, Mass., where she had a modest one-story house.

She wrote in The Wall Street Journal in 2011, explaining her “Full confession: I am no fan of perfection”:

“I have spent a good part of my life in a small New England town with a priceless American heritage where such over-the-top perfectionism simply does not exist. There are offbeat and off-kilter compromises by carpenter-builders trying to follow the examples in English pattern books in the new towns of the New World, dealing with costs and shortages, substituting materials, inventing their own details. The 18th-Century house built for the richest man in town is made of wood cut in blocks to simulate stone that was not available. This place is genuine; its buildings retain the hallmarks of its history, something that can never be imitated or reproduced, and there is not a perfect thing anywhere — for which I am eternally grateful.”

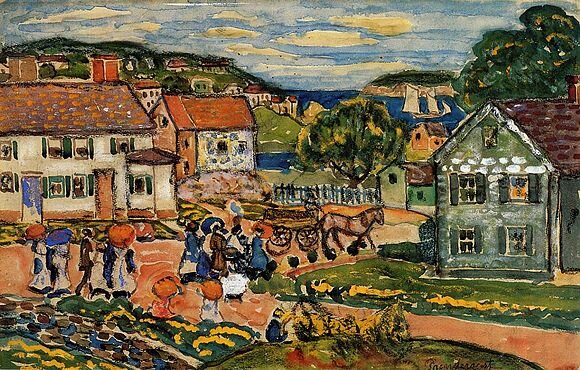

“Marblehead” (watercolor), by Maurice Prendergast (1914), in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Crowded Marblehead Harbor in high summer

The Amoskeag complex in 1911, during its textile-making heyday

Her biggest impact on New England probably came in her 1968 New York Times article “Lessons in Urbicide,” about the proposed destruction of the vast Amoskeag mill complex on the Merrimack River in Manchester, N.H.

She wrote: “The story of the destruction of the Amoskeag mill complex that has formed the heart of Manchester, N.H., for over a hundred years has a terrible pertinence for the numberless cities committing blind mutilation in the name of urban renewal. . . . We are making a dull porridge of parking lots and cheap commercialism, to replace the forms and evidence of American civilization.”

As it turned out, the complex was saved and repurposed.

David Warsh: Getting beyond despair: Three prongs to address climate change

— By Adam Peterson

Flooding caused by Super Storm Sandy in Marblehead, Mass., on Oct. 29, 2012

From economicprincipals.com

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weighed down by not knowing what to expect of the coronavirus timetable, I spent a day last week reading about climate change. Specifically, I read Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Paradoxically I came away feeling better. Grim though the situation they describe is, theirs is anything but a counsel of despair.

For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and provided unrealistic reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. It hasn’t worked out, say Alby and Zeckhauser.

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 imposed binding commitments on industrial nations to reduce emissions below 1990 levels in a decade. They exceeded them. Even so, global carbon dioxide emission grew 57 percent over the same ten years, because developing nations hadn’t joined the accord.

So the Paris Agreement of 2015 established “pledge and review” commitments by from virtually every nation in the world, designed to prevent warming of more than 2 degrees centigrade by 2030. But even if every country honors its pledge, the policy is unlikely to succeed in meeting the target, say Aldy and Zeckhauser,

That’s because what’s already in the atmosphere is a stock, not a flow. From the pre-industrial period to 1990, carbon dioxide concentration increased by about 75 parts per million. Since 1990, CO2 has increased by another 55 parts per million, and despite the agreements, the rate of increase is apparently accelerating.

Meanwhile, global temperature have increased around half a degree centigrade in the last 30 years. They are likely to rise faster in the years ahead. Storms, droughts, floods, fires, melting will increase. Mass migrations in response to these weather events have barely begun.

So, the authors say, after 30 years of single-minded stress on emission reductions in climate change discourse, two other policy prongs are urgently needed.

One of these headings, adaptation, is well-known and uncontroversial, except that it costs a lot in more complicate applications than in simple adjustments. Moving heating plants from basements to upper stories so that equipment is not damaged by flooding is simple and relatively cheap. Sea barriers and storm gates to protect coastal cities are another. The sea wall to protect the Venice lagoon is almost finished, but the Army Corps of Engineers plan to protect New York City would take 25 years to construct.

The other strut, amelioration, is considerably less discussed, mainly for fear of the ease with which the remedy may be embraced, once the cost differences are better understood. “Solar radiation management” means putting a sunscreen into the sky – most likely sulfur particles injected into the upper atmosphere by specially built airplanes. Major volcanic eruptions over the centuries have proven that the principle will work, though myriad details of its practical application are hazy. What’s clear is that so-called “geo-engineering” would cost considerably less than emissions reduction or adaptation, especially if time were of the essence.

The only place I see radiation management brought up regularly in the things I read is in Holman Jenkins’s twice-a-week column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. The other day Jenkins noted Amazon’s Jeff Bezos’s intention to spend $10 billion to fight climate change. Don’t spend it touting nuclear power, Jenkins advised; Bill Gates is already working on that. And never mind carbon taxation; that must come, if it comes, from the Left. Instead, why not atmospheric aerosol research?

Right though Jenkins may be about the possibilities of solar-radiation mitigation, he is preaching to those ready to be converted. That’s why I was interested in the Aldy-Zeckhauser paper: they are several steps closer to the mainstream. Aldy served as the Special Assistant to the President for Energy and Environment in 2009-2010. Zeckhauser works in in the tradition of tough-minded cooperation pioneered by his mentor, the policy intellectual (and Nobel laureate) Thomas Schelling.

But if we can’t handle a virus, what hope is there of devising effective policies against climate change? That’s just the point: we can handle a virus. It just takes a year, or, probably, two. The problem of arresting global warming is much more difficult, but if you believe the science, there can be no doubt that disastrous events will sooner or later cause public opinion around the world to come around

Wisdom begins with the recognition that there are three policy prongs with which to address the problem of greenhouse gases, not just one. Slowing the effects of carbon dioxide emissions – while continuing to slow emissions themselves – turns on the next election, and the two or three elections after that.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

web design by PISH P

A town on 'uncouth' ledges

Marblehead in a 1905 postcard.

"They have covered a bare and uncouth cluster of gray ledges with houses, and called it Marblehead {Mass.} These ledges stick out everywhere; there is not enough soil to cover them decently. The original gullies intersecting these ledges were turned into thoroughfares, which meander about after a most lawless and inscrutable fashion...We expect to see sailors in pigtails, citizens in periwigs. and women in kerchiefs and hobnail shoes, all speaking in an unintelligible jargon.''

-- Samuel Drake, writing in A Book of New England Legends and Folk Lore (1872)