John O. Harney: The changing public perceptions of higher education

View of Middlebury College, in the quintessential college town of Middlebury, Vt., with the Green Mountains in the background.

Via the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

American confidence in higher education began waning at just the time that more people began to see colleges as more concerned about their bottom lines than about education and making sure students have a good education experience, Public Agenda President Will Friedman told educators gathered in Boston on Monday at a NEBHE panel discussion on “The Changing Public Perceptions of the Value of Higher Education: Is It a Public Good?”

The discussion was moderated by Kirk Carapezza, managing editor at WGBH, a NEBHE partner. N.H state Rep. Terry Wolf, a NEBHE delegate, offered one state’s response.

The benefits of going to college and the importance of higher education institutions were once held to be a creed as American as apple pie. But recurring state budget challenges have constrained investment. Consistently rising tuitions—fueled by increasing college costs—have alarmed many. Politics and free-speech controversies have raised questions about college and universities’ openness and balance of perspectives. In short, times have changed.

Questions swirl:

How are public opinions toward higher education changing?

Why are higher education’s value propositions suspect in the eyes of some policymakers and citizens?

Does this division mirror party lines?

Has higher education been fairly—or falsely—tarred as inefficient?

Has the higher ed enterprise overcompensated for these perceptions by obsessing with business models and efficiency?

What has this apparent shift meant to egalitarian higher education concepts such as need-blind admissions, sabbaticals (ideally to pursue deep thinking), basic vs. applied research, and tenure (especially to protect academic freedom)?

What has it meant for the role of expert faculty informing civic policy outside academe and enriching discourse as “public scholars”?

What about the role of so-called “college towns” sustaining bookstores, theaters, cafes and other businesses favored by college students, budding entrepreneurs, faculty and visitors?

NEBHE was an “early adopter” of the higher education-economic development connection. What role can NEBHE play in balancing New England’s interest in advancing knowledge … and growing its knowledge economy?

Friedman said it wouldn’t be a tremendous shock if prospective students were beginning to question the value of higher ed. Every major institution except the military and libraries have lost major credibility, he said.

Most people still believe higher education is the key to the American dream. And indeed, a surfeit of data continues to show that the more higher education one has, the higher their salary. (Notably, Tom Mortenson, the longtime publisher of Postsecondary Education Opportunity, has also compiled trend data showing states with better-educated populations show better measures of economic, civic, physical and social health, ranging from higher citizen voting rates to lower infant mortality rates.)

But after years of going up, the percentage of people saying higher ed is necessary to success has begun to go down. One reason is student debt. Another is the decline in stable middle-class jobs.

Plus, there’s a partisan dynamic. Pew research shows that among Republicans specifically, the question of whether higher ed has a positive effect in the country fell off the cliff in 2015. In a 2017 survey from Civis Analytics, 46% of Republicans said they were concerned that colleges were pushing people toward a specific political view, compared with 5% of Democrats.

Carapezza recalled that when his WGBH crew visited schools in Germany, they learned that student debt was viewed there as shame (one audience member whispered that it's also seen that way in U.S. minority neighborhoods). Higher ed in Germany, Carapezza said, is seen as a public good, whereas here it is seen as a private gain.

Wolf conceded that some legislators would be happy to totally defund higher education. And negative perceptions spread quickly via social media. She urged leaders to change the way they talk about higher education. If you have a bachelor’s degree it means you can make a million dollars more over your career than someone with a high school diploma only. So why doesn’t an ad campaign promote the chance to make a million dollars?

Plus, a legislator, Wolf said she has to take care of senior citizens and tackle the opioid epidemic before helping college students who, she noted, could be aided less expensively though dual enrollment with high schools.

Some audience members lamented that we were educating too many social workers vs. carpenters (because you can see what they do)—somewhat reminiscent of a campaigning Marco Rubio’s concerns that we need more welders and fewer philosophers.

Of course, we need both.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education, part of NEBHE.

Will they still love him anyway?

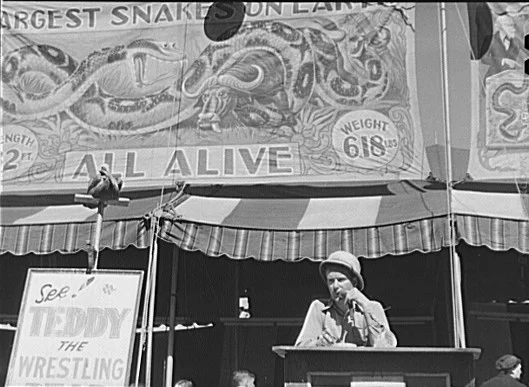

Barker at the 1941 Vermont State Fair.

--- Photo by Jack Delano

Fox News, the broadcast wing of the Republican Party, last night applied its fact-checking skills to Donald Trump’s often absurd, contradictory, chaotic and fact-free “policy’’ prescriptions, while mostly giving Ted Cruz and the man whom Mr. Trump calls “Little Marco’’ Rubio a pass. The GOP establishment is terrified that the real estate developer/operator and “reality TV’’ star will win the nomination and drag the party into an historic defeat in the fall. Yes, he would.

Of course, Messrs. Cruz and Rubio’s allegiance to the truth has also sometimes been erratic, and they too are not averse to demagoguery, but Donald Trump is in another league. His career has been one con after another.

See: www.trumpthemovie.com

A question is whether Mr. Trump’s followers and potential followers see the way the debate was run -- to bring him down -- as unfair pilling on, leading Trumpists to double-down on their support of the carnival barker.

Unfortunately for their credibility, and even morality, all three non-Trump candidates on the stage said that they'd support the New Yorker if he wins the nomination. How could they in good conscience endorse someone Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio (John Kasich was milder) called dangerous, corrupt and otherwise immoral? They have been gentler even to Hillary Clinton.

Meanwhile, the amiable John Kasich took credit last night, as do other national politicians active in the ‘90s, for the prosperity and federal budget surpluses of the late ‘90s.

In fact, those happy things resulted from the money freed up by “peace dividend’’ from the end of the Cold War, an income-tax increase accepted bravely by President George H.W. Bush and the explosion in computer/Internet business, especially after Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web, in 1989. The last brought in tons of tax revenue and gave new high-paying jobs to many people, albeit mostly the well-educated.

Mr. Kasich had nothing to do with any of that. But he seems to be a nice man and a competent governor of Ohio, though I would have preferred to see the brilliant and innovative former governor of Indiana, and now president of Purdue University, Mitch Daniels on the stage instead.

-- Robert Whitcomb

David Warsh: "System of 1896'' and GOP hopes for decades of power

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

So impatient am I with the Trump phenomenon that I spent a good part of the week reading The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters, by Karl Rove (Simon & Schuster, 2015).

I read all the way to the end to discover the answer that Rove gives — not every word of a fairly long book, mind you, but enough to get a feeling for the argument. It was an interesting time. Rove tells a good story. He had plenty of help from the published works of a quartet of academic historians – “the Modern McKinley Men,” he calls them – and from own his extensive staff.

McKinley (1843-1901), the 26th president of the United States, rose to prominence as a young hero of the Civil War, later governor of Ohio. He is more widely remembered as the man whose assassination by an angry anarchist catapulted Theodore Roosevelt, his 42-year-old vice president, into the White House.

Yet McKinley had won two presidential elections, the first of them towards the end of a bitter depression that began in 1893. He reconfigured the political map of the day, creating Republican majorities in the Northeast, the Upper Midwest and California – just the opposite of the present day. In defeating William Jennings Bryan, he created what scholarly historians have called the “system of 1896,” which, they say, lasted until 1932. After 1896, Rove writes,

The Republican Party was no longer a shrinking and beleaguered political organization composed of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants in the North and Southern blacks being systematically stripped of their right to vote. Instead, it was a frothy, diverse coalition of owners and workers, longtime Americans and new citizens, lifetime Republicans and fresh converts drawn together by common beliefs and allegiances.

Rove, of course, is himself a practicing political operative, the consultant widely credited with producing the 2000 candidacy of George W. Bush. He served as the administration’s senior political adviser and deputy chief of staff until resigning, in August 2007. In 2010 he organized American Crossroads, a political-action committee to raise money for the 2012 elections. In 2013, he organized the Conservative Victory Project, with a view to supporting “electable” conservative candidates.

As befits an expert fundraiser, Rove ends the books with what amounts to a literary PowerPoint presentation: eight reasons for McKinley’s first victory. He conducted a campaign based on big issues, sound money and protection for infant industries. He attacked his opponent, turning a strength (free silver!) into a weakness (inflationist!). He sought to broaden the Republican base, appealing with considerable success to Catholics, labor unions and immigrants, formerly excluded groups. He put more states in play than had previously been the case. He campaigned as an outsider against traditional GOP bosses in New York and Pennsylvania. He successfully portrayed himself as an agent of change. He adopted the language of national reconciliation, in sharp distinction to Bryan. Finally, he raised plenty of money and brought his advisers into his campaign – Mark Hanna in particular. And he did all this from the comfort of his own home in Canton, Ohio –- receiving one delegation of would-be constituents after another, including a body of former Confederate soldiers, in his “Front-Porch” campaign.

In other words, says Rove, McKinley was the first modern president. If all this still seems a little remote in time, here is a video of Rove himself zestfully describing what he sees as the parallels. He writes, “McKinley’s campaign matters more than a century later because it provides lessons either party could use today to end an era of a 50-50 nation and gain the edge for a durable period.”

The really interesting part is this search for a durable edge, it seems to me, and not because I am especially interested in history. Like Rove, I am concerned mainly with the present day. Also like Rove, I believe that the US electorate is prone to subtle long-term mood swings.

Speculation about long political cycles—periodic electoral “realignments” of political parties, students of politics call them – had great vogue in the 1960s and ’70s, when Rove and I were young. Professors of political science described them, notably V.O. Key, Walter Dean Burnham, E.E. Schattschneider and James L Sundquist. Historians Arthur Schlesinger, senior and junior, popularized the idea. Recently, , of Yale University, has critically examined to good effect the idea of generation-long spans, first in a landmark article for Annual Review of Political Science, and in a subsequent book, Electoral Realignments: A Critique of An American Genre (Yale, 2004). He is certainly right when he says that contingency, strategy and valence all play a part. “Politics cannot be about waiting,” he writes, “for realignments or anything else.” Here is Mayhew’s review of Rove’s book.

And yet the narrative itch persists – before, during and after. The idea that the election of 1896, McKinley vs. Bryan, brought into existence an electoral “system” that dominated U.S. politics until 1932, has been neglected, I think, somewhat obscured by the eight-year presidency of Woodrow Wilson, which eventuated only after the Republican Roosevelt staged his third-party “Bull Moose” run in 1912. Even the Federal Reserve System was largely a Republican creation, under the leadership of Sen. Nelson Aldrich (R-R.I.). I am no historian, but I am inclined to believe Wesleyan University’s Schattschneider, who wrote: “The most substantial achievement of the Democratic Party from 1896 to 1932 was that it kept itself alive as the only party to which the country could turn if it ever decided to overthrow the Republican Party.”

Taken together, along with an account of the influence of congressional Republicans during the Wilson administration, the presidencies of McKinley, Roosevelt, Taft, Harding, Coolidge and Herbert Hoover constitute it seems to me, as coherent a period of governance as the two that followed. The realignment that followed the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 lasted until 1976, at least if you buy the argument that Richard Nixon was the last “liberal” president. The realignment that began with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, or, if you prefer, Jimmy Carter in 1976, lasted at least until 2008.

That’s where Rove comes in. He thinks that the Republican Party can gain a second wind – another 30 years or so of hegemony, if only it finds a candidate who can adopt McKinley’s tactics. This, in turn, is where Rove hopes Jeb Bush will serve. Sure enough Bush last week finally began to make his move, preparing to challenge Trump for the political fraud that he is. I still expect the contest for the nomination will come down to Bush vs. someone else – Ted Cruz, or Marco Rubio or even Chris Christie. It’s even conceivable that Bush could still beat Hillary Clinton in the general election, if all the stars were to align.

Would that outcome be the beginning of a second long skein of Republican victories? I doubt it. Rather than cycles, why not call it a zig-zag pattern? – somewhat irregular but durable shifts in majority voter preferences, every couple of generations or so? My hunch is that, for now, the GOP has had its turn. Even an unlikely Bush victory would point away from the policies enunciated in the primary campaign. National security aside, the big issues of the next twenty years in presidential politics – inequality, citizenship, climate change – have barely begun to show up.

David Warsh is a proprietor of economicprincipals.com and a longtime financial journalist and economic historian.