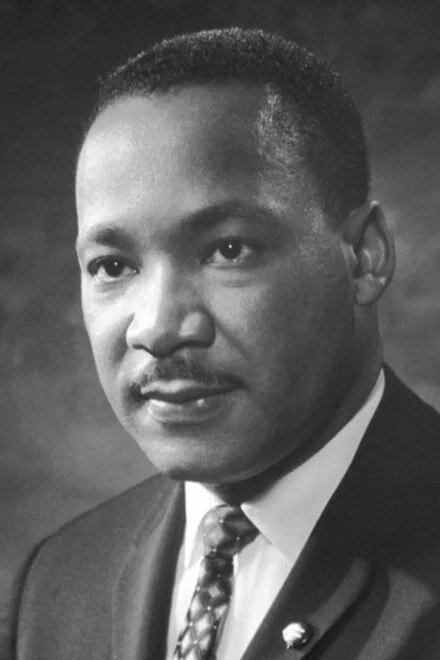

Tracey L. Rogers: Being Black is very bad for your health in America

Martin Luther King Jr., ravaged by white racism

Via OtherWords.org

After Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, on April 4, 1968, his autopsy report revealed that at the young age of 39, he had “the heart of a 60-year-old.”

Doctors concluded that King’s heart had aged due to the stress and pressure endured throughout his 13-year civil-rights career.

A 13-year tribulation sounds more fitting. Along with the victories he won through his long career preaching while organizing marches, boycotts and sit-ins, King also suffered from severe bouts of depression, received multiple threats on his life and the safety of his family, and was repeatedly arrested.

In fact, near the end of his life, as reported in Time magazine, Dr. King “confronted the uncertainty of his moral vision. He had underestimated how deeply the belief that white people matter more than others was ingrained in the habits of American life.”

There’s a reason why novelist and activist James Baldwin said in 1961, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time,” a rage that weathers our bodies and psyches.

“It isn’t only what’s happening to you,” Baldwin explained. “It’s what’s happening all around you and all of the time in the face of the most extraordinary and criminal indifference, indifference of most white people in this country and their ignorance.”

As a Black woman and activist, I can say that my rage weathers me, too.

It can feel as subtle as the frustration I feel after receiving an e-mail from a white man accusing me of being a Marxist simply because I supported the Black Lives Matter movement (true story).

Or it can be as anguishing as the pain I feel simply thinking about Jacob Blake being shot in the back seven times at point-blank range by police in Kenosha, Wis.. Or the anger I feel about the president of the United States openly fomenting violence in the shooting’s aftermath, praising the 17-year-old white militia member who killed two protesters.

If Dr. King had the heart of a 60-year-old when he died, it’s easy to see how his fight for racial justice might have weathered him. But one might argue that its weathering began the moment he was born in the era of Jim Crow, just 64-years after the formal emancipation of enslaved people.

The all-around weathering of Black America is as big a part of our legacy as slavery, voting rights, and our commitment to freedom. It’s a weathering we experience every day, agitated by what’s been diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) passed on from generation to generation.

A few years ago, an article published in Teen Vogue explained how it was possible for Black people to inherit PTSD from our ancestors. It highlighted the “extensive research into epigenetics and the intergenerational transmission of trauma” by Dr. Rachel Yehuda, who found that “when people experience trauma, it changes their genes in a very specific and noticeable way.”

Sociologist Dr. Joy DeGruy coined the phrase “post-traumatic slave disorder” to describe the specific stress suffered by Black descendants of enslaved people, identifying the ways in which racialized trauma has had an emotional, physical, and psychological impact.

More recently, the Huffington Post reported that racial trauma increases the stress hormone cortisol in Black Americans, causing fatigue, depression and anxiety. Cities throughout the country have even issued declarations that racism is a public-health issue.

They’re right.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, many chronic illnesses are far more prevalent within the Black community. And there’s a growing consensus that these illnesses are a byproduct of everyday racism. “For Black people in particular,” said psychologist Dr. Lilian Comas-Diaz, “racial stress is something that happens throughout their life course.”

Whether it’s death by “weathering,” COVID-19, or inhumane policing, evidence shows that Black lives still don’t matter. And that’s why so many of us have taken to the streets — our hearts can’t take it anymore.

Tracey L. Rogers is an entrepreneur and activist in Philadelphia.

Llewellyn King: We lost our confidence in basic rightness of America in the '60s

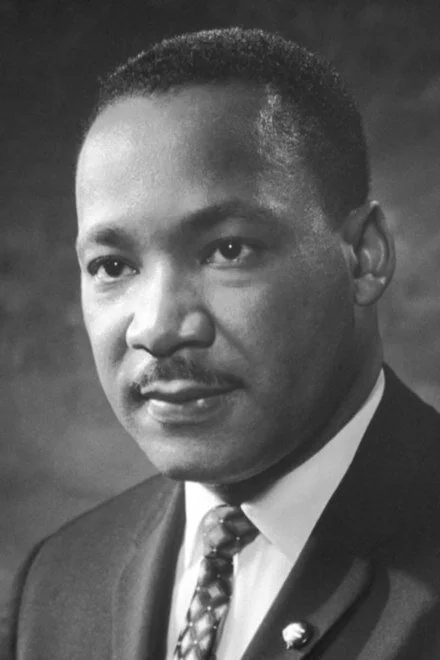

Soldiers stand guard in Washington, D.C., in the riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, was a shot that rang out like none other in the tumultuous 1960s.

Washington and many other cities erupted in riots, mostly described as race riots, but I would aver. I was there. I walked the streets of the nation’s capital, saw the looting, and had rioters protect me from fire and mayhem.

These were riots of anguish. They were, if you will, a great bellow of pain. King meant more to the African-American community of that time than we can now imagine.

If anything, right after the Washington riots, when peace was being kept by National Guard troops backing up local police, there was a surreal politeness between the races. Reporters, who were in the thick of things, wrote about it.

Later, when Congress held hearings and conservative Southern congressmen wanted to know why the District of Columbia police had not opened fire on the rioters, why they had been so restrained, race was emphasized. To its credit, the largely white police force held its fire.

Despite the civility, it was not pretty. Washington’s stores were looted and restaurants burned. On 14th Street, maybe the worst hit, I watched as a pleasant restaurant called California, as I remember, blazed while the owner stood on the street and wept, tears running down his face. He wanted to know why the police did not act, why the fire department could not save his restaurant.

The price Washington and the nation paid was high. After cataclysmic events, things do not return to the status quo ante. They are forever changed.

As King had changed the civil rights debate, so his murder changed Washington. The obvious things were a greater segregation in a city that had been quietly edging toward modest integration. At that time, we went to black-owned clubs on U Street to hear jazz, and young people like myself had black friends in a natural, not a contrived, way.

Sure, there was racism everywhere (particularly, I had found, in the police department), but there was a cozy feel to the nation’s capital. It went. White flight was almost immediate, and the move by so many whites to the suburbs changed a lot of things. Washington became a black city surrounded by white suburbs in Maryland and Virginia.

The riots were emblematic of what was happening in the tumultuous decade. It was a decade in which old values perished and were replaced with a new lack of trust in government and institutions, big and small, public and private. It persists today.

The 1960s were host to major movements, all underlaid by the Vietnam War and the loss of young American life there. It was the key in which the symphony of discontent was written.

Along with the war were the social movements, all of which fingered the establishment, the elites. There was the civil rights movement, the environmental movement, the women’s movement and a huge sense among young people that the older people could not be trusted.

These legacies of the 1960s are still with us: distrust of government, lack of confidence in expertise, suspicion of institutions, and the use of the media and the courts to achieve political and social goals.

The greatest loss to the 1960s might be patriotism. We do not have the absolute confidence in the rightness of the national cause, which had motivated what Tom Brokaw called the “greatest generation.” Craven praise of the military should not be confused with what we had in the 1940s and 1950s: selfless patriotism.

The turbulent decade put paid to the old patriotism and unleashed a new kind of social riot that is alive and well.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.