‘Greening the Labs’’ at MGH

Headquarters of Mass General Brigham, in Somerville

— Photo by Hospitalupdate

Edited from a New England Council report

“Mass General Brigham is expanding its ‘Greening the Lab’ initiative, which was concluded at five Massachusetts General Hospital labs earlier this year. Now, the research team behind the program is selecting 20 more labs from MGH’s parent organization to participate.

“The program comes from a partnership between MGH and My Green Lab, a San Diego-based nonprofit that helps increase the sustainability of biomedical research entities. The initial pilot program ensured the sustainability efforts would work in an academic medical center. According to Dr. Ann-Christine Duhaime, the associate director for research and publications at the Center for the Environment and Health at MGH, the initial results have been positive, showing that the program has effectively reduced costs, energy expenditure and hazardous-waste needs.

“‘The push to put more emphasis on sustainability has largely come from the junior researchers at the hospital,’’’ Duhaime said. ‘Creating a holistic program that brings all members of a lab together to focus on climate impact in addition to the clinical pursuits of their research has been a priority of the integration of the initiative, and initial findings have suggested that it’s increasing job satisfaction among participants.’

Judith Graham: What elderly people should know about taking Paxlovid for COVID

Paxlovid blister pack

— Photo by Kches16414

“There’s lots of evidence that Paxlovid can reduce the risk of catastrophic events that can follow infection with COVID in older individuals.’’

— Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a professor of medicine at Yale University

A new coronavirus variant is circulating, the most transmissible one yet. Hospitalizations of infected patients are rising. And older adults represent nearly 90% of U.S. deaths from COVID-19 in recent months, the largest portion since the start of the pandemic.

What does that mean for people 65 and older catching COVID for the first time or those experiencing a repeat infection?

The message from infectious-disease experts and geriatricians is clear: Seek treatment with antiviral therapy, which remains effective against new COVID variants.

The therapy of first choice, experts said, is Paxlovid, an antiviral treatment for people with mild to moderate COVID at high risk of becoming seriously ill from the virus. All adults 65 and up fall in that category. If people can’t tolerate the medication — potential complications with other drugs need to be carefully evaluated by a medical provider — two alternatives are available.

“There’s lots of evidence that Paxlovid can reduce the risk of catastrophic events that can follow infection with COVID in older individuals,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a professor of medicine at Yale University.

Meanwhile, develop a plan for what you’ll do if you get the disease. Where will you seek care? What if you can’t get in quickly to see your doctor, a common problem? You need to act fast since Paxlovid must be started no later than five days after the onset of symptoms. Will you need to adjust your medication regimen to guard against potentially dangerous drug interactions?

“The time to be figuring all this out is before you get COVID,” said Dr. Allison Weinmann, an infectious-disease expert at Henry Ford Hospital, in Detroit.

Being prepared proved essential when I caught COVID in mid-December and went to urgent care for a prescription. Because I’m 67, with blood cancer and autoimmune illness, I’m at elevated risk of getting severely ill from the virus. But I take a blood thinner that can have life-threatening interactions with Paxlovid.

Fortunately, the urgent-care center could see my electronic medical record, and a physician’s note there said it was safe for me to stop the blood thinner and get the treatment. (I’d consulted with my oncologist in advance.) So, I walked away with a Paxlovid prescription, and within a day my headaches and chills had disappeared.

Just before getting COVID, I’d read an important study of nearly 45,000 patients 50 and older treated for the disease between January and July 2022 at Mass General Brigham, the large Massachusetts health system. Twenty-eight percent of the patients were prescribed Paxlovid, which had received an emergency use authorization for mild to moderate covid from the FDA in December 2021; 72% were not. All were outpatients.

Unlike in other studies, most of the patients in this one had been vaccinated. Still, Paxlovid conferred a notable advantage: Those who took it were 44% less likely to be hospitalized with severe COVID-related illnesses or die. Among those who’d gotten fewer than three vaccine doses, those risks were reduced by 81%.

A few months earlier, a study out of Israel had confirmed the efficacy of Paxlovid — the brand name for a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir — in seniors infected with COVID’s omicron strain, which arose in late 2021. (The original study establishing Paxlovid’s effectiveness had been conducted while the delta strain was prevalent and included only unvaccinated patients.) In patients 65 and older, most of whom had been vaccinated or previously had covid, hospitalizations were reduced by 73% and deaths by 79%.

Still, several factors have obstructed Paxlovid’s use among older adults, including doctors’ concerns about drug interactions and patients’ concerns about possible “rebound” infections and side effects.

Dr. Christina Mangurian, vice dean for faculty and academic affairs at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine, encountered several of these issues when both her parents caught covid in July, an episode she chronicled in a recent JAMA article.

First, her father, 84, was told in a virtual medical appointment by a doctor he didn’t know that he couldn’t take Paxlovid because he’s on a blood thinner — a decision later reversed by his primary care physician. Then, her mother, 78, was told, in a separate virtual appointment, to take an antibiotic, steroids, and over-the-counter medications instead of Paxlovid. Once again, her primary care doctor intervened and offered a prescription.

In both cases, Mangurian said, the doctors her parents first saw appeared to misunderstand who should get Paxlovid, and under what conditions. “This points to a major deficit in terms of how information about this therapy is being disseminated to front-line medical providers,” she told me in a phone conversation.

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, agrees. “Every day, I hear from people who are misinformed by their physicians or call-in nurse lines. Generally, they’re being told you can’t get Paxlovid until you’re seriously ill — which is just the opposite of what’s recommended. Why are we not doing more to educate the medical community?”

The potential for drug interactions with Paxlovid is a significant concern, especially in older patients with multiple medical conditions. More than 120 medications have been flagged for interactions, and each case needs to be evaluated, taking into account an individual’s conditions, as well as kidney and liver function.

The good news, experts say, is that most potential interactions can be managed, either by temporarily stopping a medication while taking Paxlovid or reducing the dose.

“It takes a little extra work, but there are resources and systems in place that can help practitioners figure out what they should do,” said Brian Isetts, a professor at the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy.

In nursing homes, patients and families should ask to speak to consultant pharmacists if they’re told antiviral therapy isn’t recommended, Isetts suggested.

About 10% of patients can’t take Paxlovid because of potential drug interactions, according to Dr. Scott Dryden-Peterson, medical director of COVID outpatient therapy for Mass General Brigham. For them, Veklury (remdesivir), an antiviral infusion therapy delivered on three consecutive days, is a good option, although sometimes difficult to arrange. Also, Lagevrio (molnupiravir), another antiviral pill, can help shorten the duration of symptoms.

Many older adults fear that after taking Paxlovid they’ll get a rebound infection — a sudden resurgence of symptoms after the virus seems to have run its course. But in the vast majority of cases “rebound is very mild and symptoms — usually runny nose, nasal congestion, and sore throat — go away in a few days,” said Dr. Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious-disease physician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Gandhi and other physicians I spoke with said the risk of not treating COVID in older adults is far greater than the risk of rebound illness.

Side effects from Paxlovid can include a metallic taste in the mouth, diarrhea, nausea and muscle aches, among others, but serious complications are uncommon. “Consistently, people are tolerating the drug really well,” said Dr. Caroline Harada, associate professor of geriatrics at the University of Alabama-Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, “and feeling better very quickly.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Harris Meyer: Mass. pushing back against at pricey hospital group’s empire building

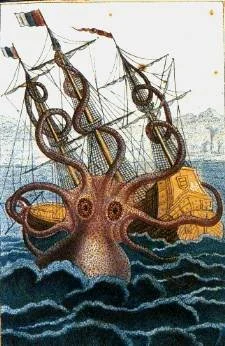

Pen and wash drawing by the malacologist Pierre de Montfort, 1801.

Front entrance of Massachusetts General Hospital.

A Massachusetts health-cost watchdog agency and a broad coalition including consumers, health systems, and insurers helped block the state’s largest — and most expensive — hospital system in April from expanding into the Boston suburbs.

Advocates for more affordable care hope that the decision by regulators to hold Mass General Brigham accountable for its high costs will usher in a new era of aggressive action to rein in hospital expansions that drive up spending. Their next target is a proposed $435 million expansion by Boston Children’s Hospital.

Other states, including California and Oregon, are paying close attention, eyeing ways to emulate Massachusetts’s decade-old system of monitoring health-care costs, setting a benchmark spending rate, and holding hospitals and other providers responsible for exceeding their target.

The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission examines hospital-specific data and recommends to the state Department of Public Health whether to approve mergers and expansions. The commission also can require providers and insurers to develop a plan to reduce costs, as it’s doing with MGB.

“The system is working in Massachusetts,” said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy, who stressed the importance of the state’s robust data-gathering and analysis program. “The focus on providing transparency around health costs has been really helpful. That’s what all states want to do. I don’t know if other states will adopt the Massachusetts model. But we’re hearing increased interest.”

With its many teaching hospitals, Massachusetts historically has been among the states with the highest per capita health-care costs, though its spending has moderated in recent years as state officials have taken aim at the issue.

On April 1, MGB, an 11-hospital system that includes the famed Massachusetts General Hospital, unexpectedly withdrew its proposal for a $223.7 million outpatient-care expansion in the suburbs after being told by state officials it wouldn’t be approved.

That expansion would have increased annual spending for commercially insured residents by as much as $28 million, driving up insurance premiums and shifting patients away from lower-priced competitors, according to the commission.

This marked the first time in decades that the state health department used its authority to block a hospital expansion because it undercut the state’s goals to control health costs.

Other parts of MGB’s $2.3 billion expansion plan also met resistance.

The health department staff recommended approving MGB’s proposal to build a 482-bed tower at its flagship Massachusetts General Hospital and a 78-bed addition at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. But they urged rejecting a request for 94 additional beds at MGH.

The department’s Public Health Council, whose members are mostly appointed by the governor, is scheduled to vote on those recommendations May 4.

The health policy commission, which works independently of the public health department but provides advice, has also required MGB to submit an 18-month cost-control plan by May 16, because its prices and spending growth have far exceeded those of other hospital systems. That was a major reason the growth in state health spending hit 4.3 percent in 2019, exceeding the commission’s target of 3.1%.

This is the first time a state agency in Massachusetts or anywhere else in the country has ordered a hospital to develop a plan to control its costs, Hensley-Quinn said.

MGB’s $2.3 billion expansion plan and its refusal to acknowledge its high prices and their impact on the state’s health costs have united a usually fractious set of stakeholders, including competing hospitals, insurers, employers, labor unions and regulators. They also were angered by MGB’s lavish advertising campaign touting the consumer benefits of the expansion.

Their fight was bolstered by a report last year from state Atty. Gen. Maura Healey that found that the suburban outpatient expansion would increase MGB annual profits by $385 million. The nonprofit MGB reported $442 million in operating income in 2021.

The Massachusetts Association of Health Plans opposed the MGB outpatient expansion.

The well-funded coalition warned that the expansion would severely hurt local hospitals and other providers, including causing job losses. The consumer group Health Care for All predicted the shift of patients to the more expensive MGB sites would lead to higher insurance premiums for individuals and businesses.

“Having all that opposition made it pretty easy for [the Department of Public Health] to do the right thing for consumers and cost containment,” said Lora Pellegrini, CEO of the health plan association.

Republican Gov. Charlie Baker, who has made health-care cost reduction a priority and who leaves office next January after eight years, didn’t want to see the erosion of the state’s pioneering system of global spending targets, she said.

“What would it say for the governor’s legacy if he allowed this massive expansion?” she added. “That would render our whole cost-containment structure meaningless.”

MGB declined to comment.

Massachusetts’s aggressive action examining and blocking a hospital expansion comes after many states have moved in the opposite direction. In the 1980s, most states required hospitals to get state permission for major projects under “certificate of need” laws. But many states have loosened or abandoned those laws, which critics say stymied competition and failed to control costs.

The Trump administration recommended that states repeal those laws and leave hospital-expansion projects up to the free market.

But there are signs the tide is turning back to more regulation of hospital building.

Several states have created or are considering creating commissions similar to the one in Massachusetts with the authority and tools to analyze the market impact of expansions and mergers. Oregon, for example, recently passed a law empowering a state agency to review health care mergers and acquisitions to ensure they maintain access to affordable care.

Despite the defeat of MGB’s outpatient expansion, Massachusetts House Speaker Ron Mariano, a Democrat, said the state’s cost-control model needs strengthening to prevent hospitals from making an end run around it. A bill he backed that passed the House would give the commission and the attorney general’s office a bigger role in evaluating the cost impact of expansions. The Senate hasn’t taken up the bill.

“Hospital expansion is the biggest driver in the whole medical expense kettle,” he said.

Meanwhile, cost-control advocates are eager to see how MGB proposes to control its spending, and how the Health Policy Commission responds.

“Unless MGB somehow agrees to limit increases in its supranormal pricing, like a five-year price freeze across the system, I don’t know that the [plan] will accomplish anything,” said Dr. Paul Hattis, a former commission member.

Hattis and others are also waiting to see how the state rules on a bid by Boston Children’s Hospital, another high-priced provider, to build new outpatient facilities in the suburbs.

“For those of us on the affordability side, it’s like the sheriffs rediscovered their badge and realized they really could say no,” he said. “That’s a message to other states that they also should constrain their larger provider systems, and to the systems that they can no longer do whatever they please.”

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Harris Meyer: Resistance to Mass General Brigham expansion centers on fear of higher prices

MGH Brigham complex in Foxboro, Mass.

— Photo by Patriot-place

A boisterous political battle over a proposed expansion by the largest and most expensive hospital system in Massachusetts is spotlighting questions about whether similar expansions by big health systems around the country drive up health-care costs.

Boston-based Mass General Brigham, which owns 11 hospitals in the state, has proposed a $2.3 billion expansion, including a new 482-bed tower at its flagship Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a 78-bed addition to Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. The most controversial element, however, is a plan to build three comprehensive ambulatory-care centers, offering physician services, surgery and diagnostic imaging, in three suburbs west of Boston.

On Jan. 25, the state’s 11-member Health Policy Commission unanimously concluded that these expansions would drive up spending for commercially insured residents by as much as $90 million a year and boost health- insurance premiums.

The commission also ordered Mass General Brigham to develop an 18-month “performance improvement plan” to slow its cost growth. The action, believed to be the first time in the country a hospital has been ordered to develop a plan to control costs, reflects concern about giant hospitals’ role in rising health care costs.

Other states, including California, Delaware, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington, have created or are considering commissions on health care costs with the authority to analyze the market impact of mergers and expansions. That’s happening because the traditional “determination of need” process for approving health facility expansions, which nearly three dozen states still have in place, has not been effective in the current era of health system giants, said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior program director at the National Academy for State Health Policy.

The Mass General Brigham health system, which generates $15.7 billion in annual operating revenue, announced that the massive expansion would better serve its existing patients, including 227,000 who live outside Boston. Its leaders said the new facilities would not raise health spending in the state, where policymakers are alarmed that cost growth in 2019 hit 4.3%, exceeding the state’s target of 3.1%.

The hospitals’ cost-analysis report, submitted to the state last month, concluded that the system’s existing patients would pay lower prices at the new suburban sites than at its downtown locations. John Fernandez, president of Mass General Brigham Integrated Care, projected that prices at the new centers would be 25% less, and he said patients will not have to pay extra hospital “facility fees” at the new outpatient sites.

“We’re all going to have a tsunami of patients over the next 20 years given the aging population, and everyone has to step up to meet that demand,” he said in explaining the expansion.

But a well-funded coalition of competing hospitals, labor unions and chambers of commerce argues that Mass General Brigham’s invasion of the Boston suburbs would spike total spending by drawing in patients from lower-priced physicians and hospitals. They cite the health system’s own planning projection, unearthed by the attorney general’s office in a November report, that the expansion would boost annual profits by $385 million.

Dr. Eric Dickson is CEO of UMass Memorial Health Care, a safety-net health system serving the towns west of Boston that is part of the coalition of opponents to Mass General Brigham’s expansion plans. “If you let the state’s most expensive system grow wildly, it will drive up the cost of care,” he says.(UMASS MEMORIAL HEALTH CARE)

“How could you be fooled?” said Dr. Eric Dickson, CEO of UMass Memorial Health Care, a safety-net health system serving the towns west of Boston that is part of the coalition of expansion opponents. “If you let the state’s most expensive system grow wildly, it will drive up the cost of care.”

The controversy signals a shift in the concerns about the cause of rapidly escalating health care costs. Up to now, state and federal policymakers examining how hospital system growth affects costs have largely focused on hospital mergers and purchases of physician practices. Studies have found that these deals significantly boost prices to consumers, employers, and insurers. State and federal regulators have stepped up antitrust scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions.

Deep-pocketed hospital systems increasingly are turning to solo expansion to gain a bigger share of the market. These expansions fall outside the legal authority of antitrust enforcers.

Health systems are building satellite ambulatory care centers to attract more well-insured patients and steer them to their own hospitals and other facilities, said Glenn Melnick, a health economist at the University of Southern California.

“The outcome is the same as a merger — capturing patients and keeping them,” he said. “That’s not necessarily good for consumers in terms of access to care or cost efficiency.”

Critics of Mass General Brigham’s plans also warn that the expansion would financially destabilize providers that heavily serve lower-income and minority residents because some of their more affluent patients would move to the new facilities. Those patients’ commercial insurance plans pay nearly three times what the state’s Medicaid program pays.

“It’s a very, very good business move for MGB,” said Dickson, whose system serves a large percentage of Medicaid patients. “But they know quite well this will impact our ability to care for vulnerable populations.”

The Health Policy Commission agreed with those opposing the expansion and said it would advise the state Public Health Council — which will decide on the three expansion applications by April — that the proposals are not consistent with the state’s goals for cost containment.

“Our strong assessment is this would substantially increase spending,” said Stuart Altman, a health policy professor at Brandeis University who chairs the commission. In addition, “there is a clear indication it would reduce revenues to those institutions we count on to provide services to lower-income and historically marginalized communities.”

In a written statement, Mass General Brigham ripped the commission’s findings as flawed. It also disagreed with the commission’s decision to require a cost-improvement plan but said it would work with the agency to address the challenge.

Under Massachusetts’s determination of need process, Mass General Brigham must show the Public Health Council that its expansion proposals would contribute to the state’s goals for cost containment, improved public health outcomes, and delivery system transformation.

The council has never blocked a project on cost grounds in its nearly 50-year history, said Dr. Paul Hattis, a former member of the Health Policy Commission. He argues that Massachusetts needs more explicit statutory power to decide whether health system expansions are good for the public, because he doesn’t think the council understands its own regulation.

A bill passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives last fall would give the commission, which was created in 2012, greater authority to investigate the cost and market impact of such expansions. Its legislative fate is uncertain.

Upping the stakes in the Massachusetts expansion fight: Massachusetts General Hospital charges by far the highest prices in the state, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital isn’t far behind.

Patients with a Mass General Brigham primary care physician had the highest total per-member spending in 2019, nearly $700 per month, according to the Health Policy Commission. That was 45% higher than spending for patients served by doctors at Reliant, which is owned by UnitedHealth Group’s Optum unit. Average payments for major outpatient surgery at Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s were nearly twice as high as at the state’s lowest-paid high-volume hospital.

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Harris Meyer: @Meyer_HM

More efficient and more expensive?

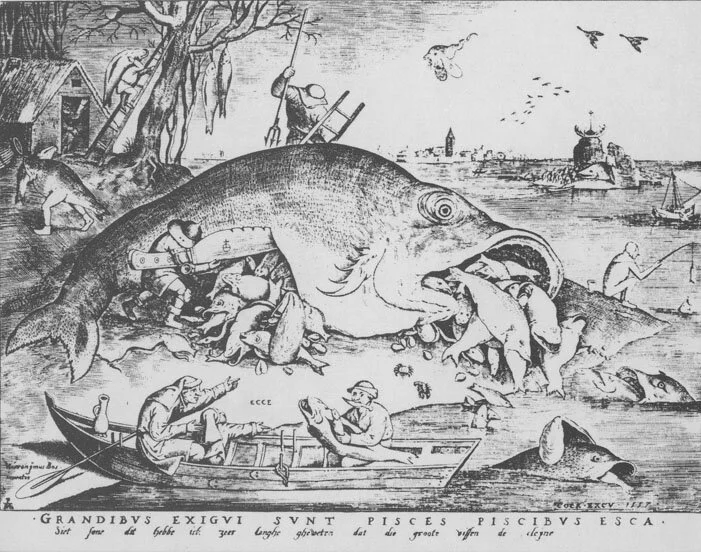

“The Big Fish Eat the Small Ones,’’ by Peter Brueghel the Elder (1556).

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“The sooner patients can be removed from the depressing influence of general hospital life the more rapid their convalescence.’’

-- Charles H. Mayo, M.D. (1865-1939), American physician and a co-founder of the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn.

The plan for Lifespan and Care New England (CNE) to merge, if regulators approve it, would probably make Rhode Island health care more efficient. It would do this through integrating their hospitals and other units. That would do such things as speeding the sharing of patient information among health-care professionals and streamlining billing. Further, it would probably strengthen medical research and education in the state, much of it through the new enterprise’s very close links with the Alpert Medical School at Brown University, which, indeed, has pledged to provide at least $125 million over five years to help develop an “academic health system’’ as part of the merger.

The deal, by reducing some red tape (with the state having just one big system instead of two), might make health care in our region more user-friendly for patients, dissuading more of them from going to Boston’s world-renowned medical institutions, thus keeping more of their money here.

The best example of where the merger could improve health care would be in better connecting Lifespan’s Hasbro Children’s Hospital with Care New England’s Bradley Hospital, a psychiatric institution for children, and Women & Infants Hospital.

But would the huge (especially for such a tiny state) new institution have such power that it would impose much higher prices? Studies have shown that hospital mergers almost inevitably mean higher prices. So insurance companies, as well as poorly insured patients, may eye a Lifespan-CNE merger with trepidation.

And expect job losses, at least for a while, given the need to eliminate the administrative redundancies created by mergers. Meanwhile, senior- executive salaries in the new entity would probably be even more stratospheric than they are now at the separate “nonprofit” companies, and I imagine the golden parachutes for departing excess senior execs would blot out the sun.

Meanwhile, Boston will remain a magnet for health care, and so it’s conceivable that the behemoth and very prestigious Mass General Brigham hospital group would end up absorbing the Lifespan-CNE giant in the end anyway.

Finding genetic variations in severity of COVID-19 symptoms

— Photo by Tim Pierce

Here’s the latest roundup of COVID related developments in the region from The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

“Researchers at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center have shed light on COVID-19 symptom severity with new research. The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, reveals the role of genetic variations in the severity of COVID-19 symptoms. Read more here. And:

Mass General Brigham has joined with news publications as well as hospitals and health systems across the country to urge people to continue to wear masks during this critical period. Read more here.

Harvard University Medical School researchers have created a new tool for the creation of new adult cells for research. The new Human TFome systems will allow cells to be customized by researchers to the disease they are studying. Read more here.’’

UMass Memorial plans Worcester field hospital for COVID-19 patients

The DCU Center (originally Centrum) is an indoor arena and convention center complex in downtown Worcester.

Here’s The New England Council’s (newenglandcouncil.com) latest roundup of COVID-19 news in our region:

* ‘‘UMass Memorial Health Care has laid plans for a field hospital in the DCU Center in Worcester. (DCU stands for Digital Federal Credit Union.) The field hospital was decommissioned last spring; however, UMass Memorial has since been preparing to open the site once again in anticipation of another surge in COVID-19 related hospitalizations. Read more here.’’

* ‘‘ Mass General Brigham and Beth Israel Lahey Health are reporting that their hospitals are better prepared for a second COVID-19 wave. Hospital officials are in communication to balance COVID-19 patients across multiple sites in the Greater Boston area if the need arises. Read more here. ‘‘

* ”The American Hospital Association has produced a podcast providing useful information on patient wellness, preventing chronic diseases, and prioritizing quality and patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more here. ‘‘

* ’’ (Boston-based) Harbor Health Services has partnered with instaED Paramedics to provide elders who participate in their Elder Service Plan (ESP) with at-home urgent care. The program will allow participants to receive treatments normally provided in the emergency room while safe at home. Read more here.’’