The Mass. surtax experiment

In ancient times, Egyptians seized for failing to pay taxes.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Massachusetts collected about $1.8 billion from a new voter-approved levy on rich residents through the first nine months of this fiscal year; the year ends June 30. That’s $800 million more than what the legislature and Gov. Maura Healey had projected for this revenue for all of fiscal 2024! The levy, which many call “the millionaires’ tax,’’ is a 4 percent surtax on personal income over $1 million.

The money is supposed to go to transportation (especially in fixing and expanding the MBTA, which, reminder, also serves Rhode Island) and education. A big question is whether those improvements, by making the state more competitive from a physical-infrastructure and services standpoint, will more than offset the macroeconomic effects of folks taking their money to such tax havens for the affluent as New Hampshire, “The Parasite State,” with their much thinner public services.

Some businesspeople, for example, might decide that education and transportation improvements financed by the surtax will make the state enough of a better place to make money in the long term as to more than offset the increase in their income tax. Of course, for many millionaires and billionaires, any tax is too much; and they don’t need many of the public services used by the poor and middle class, including public schools, though I suppose they do like having, say, highways and airports.

We’ll probably know within a couple of years how this tax experiment is working out, and what the lessons might be for other states, especially in New England, though a recession may make it difficult to measure its long-term effects. It seems unlikely that Red States, most of which are in the South, will do anything like it. Rich folks have too much power there. But some Blue States might try variants of the Massachusetts experiment.

Birds' spring songs may be coming earlier

Chickadees’ songs cheer up New Englanders in their shortening winters. The species shown here, the Black-Capped Chickadee, is the state bird of Massachusetts.

Song sparrow

‘On any given, relatively warm winter day, the melodies of song sparrows and chickadees float down from the trees.

“Hearing birdsong in early winter is both a natural and unnatural phenomenon, according to ornithologists. As days get longer and warmer, the birds’ internal clocks urge them to sing.

“That’s why you may hear birds that live here year-round, like the chickadee, or that winter here but breed father north, like the American robin, sing during nice weather, according to Salve Regina University professor Jameson Chase. ‘So, not unusual and certainly not on warm days.’

“But with spring-like weather coming earlier and earlier due to climate change, some of the songs of the season may be coming a little earlier, too.’’

Please hit this link to read the whole article, by Colleen Cronin

‘Inhabitant of the Mind’

“I perceive that I am neither a planter of the backwoods, pioneer, nor settler there, but an inhabitant of the Mind, and given to friendship and ideas. The ancient society, the Old England of New England, Massachusetts for me.”

— Amos Bronson Alcott (1799 -1888) American teacher, writer, philosopher and reformer and long-time resident of the intellectual community of Concord, Mass.,

Always headwinds

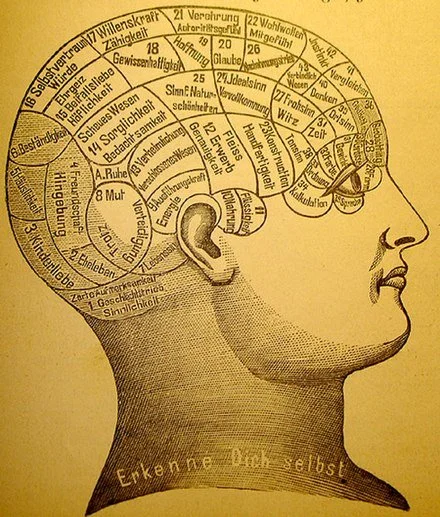

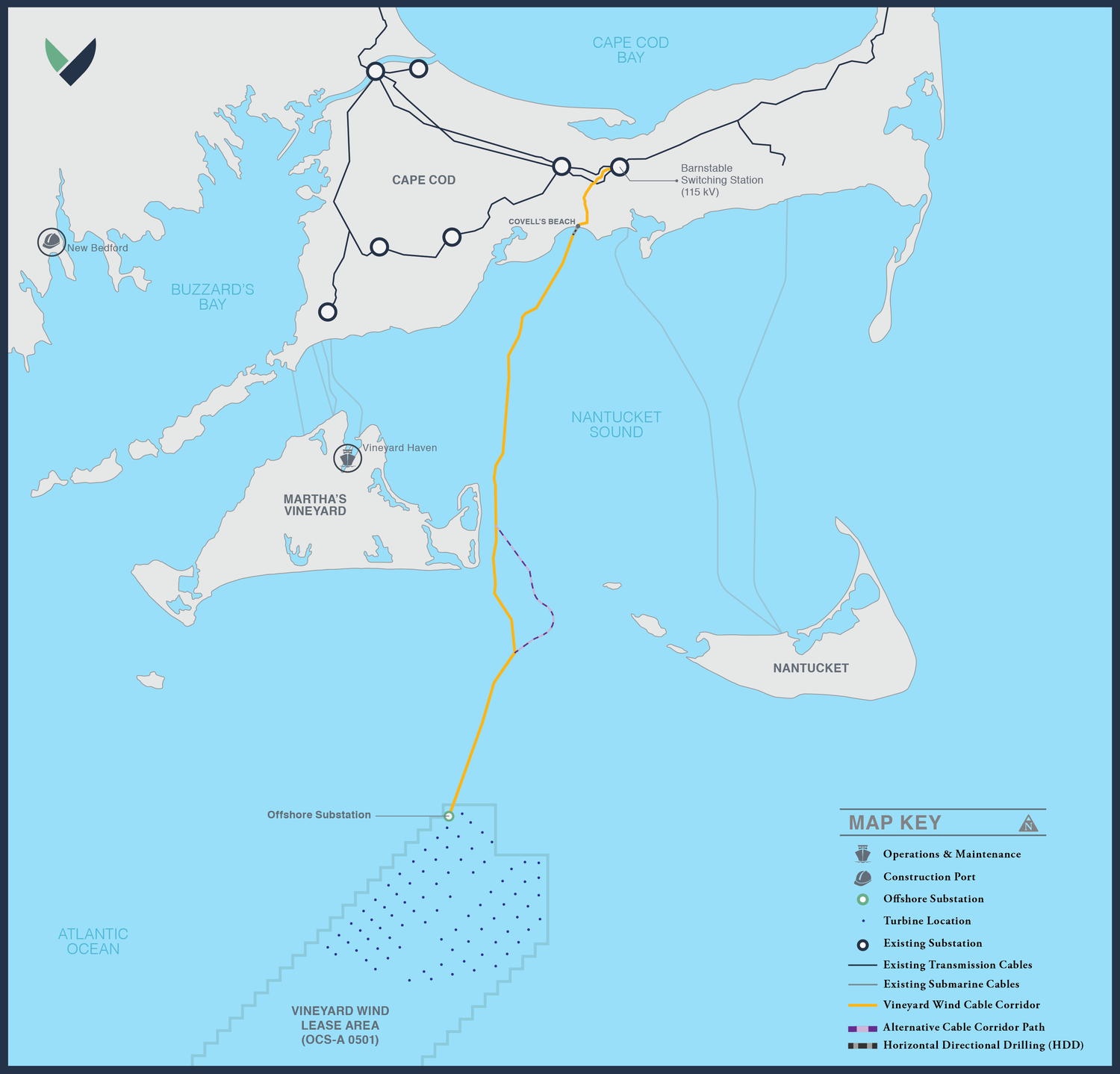

Wind-energy lease areas off Massachusetts and Rhode Island as of October, 2022

The Massachusetts Wind Technology Testing Center, in Boston’s Charlestown section.

— Photo by vArnoldReinhold

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was good to hear that the U.S. Interior Department has approved Revolution Wind’s big (700 megawatts) project, southwest of Martha’s Vineyard. The project could provide electricity for 350,000 homes and create about 1,200 construction jobs.

The department has also approved the Vineyard Wind 1 project, off Massachusetts, the South Fork Wind project, off Rhode Island and New York, and the Ocean Wind 1 project, off New Jersey.

But the regulatory approval process moves at glacial speed, and litigation always threatens to stop such projects in their tracks. Big factors are nimbyism by coastal residents (often led by affluent summer people) who say that they don’t want to look at wind turbines, as well as opposition by some in the fishing sector because of the mostly temporary disruptions in the areas where they’d be installed. Of course, the damage caused by man-made global warming happens everywhere, in varying degrees of severity.

And the supports for offshore turbines act as artificial reefs that draw fish. Wouldn’t fishermen like that?

Installing any energy source creates problems, but let’s make rational comparisons….

The complaints by offshore-wind foes are outstandingly hypocritical. Consider that the fossil-fuel burning that wind power is meant to partly replace poses an existential risk to fishing interests by dangerously warming and acidifying the water and disrupting major ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream. Fossil-fuel burning destroys food sources of marine animals, including whales.

Then there are those pesky oil spills and the disruptions to marine animals by speeding oil tankers.

When you look closely at opposition to coastal and offshore wind projects you see money from – you guessed it! – the oil and gas industry.

Take a look at the stuff in these links:

https://electrek.co/2022/04/18/the-first-us-offshore-wind-farm-has-had-no-negative-effect-on-fish-finds-groundbreaking-study/

https://grist.org/politics/republicans-fossil-fuels-the-gop-donors-behind-a-growing-misinformation-campaign-to-stop-offshore-wind/

Animal rights and abuses in New Bedford show

“Massachusetts State of the Union,’’ by Providence/West Palm Beach artist Jane O’Hara, in the show of the same name at the New Bedford Art Museum, through Aug. 20

— Photo courtesy New Bedford Art Museum.

The museum explains that the show looks at animal rights and the complex relationship between humans and other animals. “Covering the 50 states of the union, O'Hara's work examines animal rights abuses through the lens of classic ‘wish-you-were-here postcards.’’’

#Jane O’Hara #New Bedford Art Museum

Ripen, then leave

Victorian-era row houses in Springfield, built in the city’s industrial heyday.

“Springfield, Massachusetts, is a place to be from. Talented people ripen in Springfield, then move away to larger cities to make their fortune.’’ (Like Theodor Geisel, the Springfield native later known as Dr. Seuss.)

— James C. O’Connell, in Pioneer Valley Reader (1995)

Money just for education and transport?

Will the “millionaires tax’’ drive any of the rich folks living in fancy streets like this on Boston’s Beacon Hill to move their official residences to Florida or New Hampshire?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Massachusetts voters, by a 52-48 percent margin, approved what’s been dubbed “the millionaires’ tax’’ in the Nov. 8 election.

The Bay State has had a flat rate of 5 percent of federal adjusted gross income. A new constitutional amendment will add an additional 4 percent tax on taxable income over $1 million, starting in 2023, in a modest move to progressive taxation. (Federal taxation has progressive elements and unprogressive ones, the latter including shielding more income from capital gains than from earned income, favoritism that benefits the affluent.)

A Tufts University study projects that the “millionaires’ tax’’ will bring in about $1.3 billion next year, and that the levy would only affect 0.6 percent of households.

Proponents promise that all the money to be raised by the new tax would go to education and transportation. If that actually happens, it could strengthen the commonwealth’s – and New England’s – economy. Despite all the promotion of the Sun Belt’s tax systems – good for the rich, but not particularly for the poor and middle class, which are saddled with highly regressive sales taxes in these mostly Red States – the wealthiest states continue to be those willing to pay for good public services.

But would a recession, causing Massachusetts’s state tax revenues to fall, end up forcing the state to use much, or all, of that $1.3 billion to balance its budget? Could well happen next year in the predicted recession because there’s nothing to legally compel officials to spend the money just on schools and transportation (presumably mostly the MBTA, including trains to and from Rhode Island).

In any event, because of the new tax, a few rich folks will leave, and/or threaten to leave, the Bay State to go to Florida, that paradise of income-tax avoiders, money launderers, gigantic, floodable oceanside mansions, inland tarpaper shacks, big donors to GOPQ campaigns, 7-Elevens, terrifyingly wide intersections and Burmese pythons, or to, say, New Hampshire, which prospers in no small degree because it’s next to the great wealth creator of Greater Boston, in a state that’s willing to pay for extensive public services that support that wealth creation.

(While New Hampshire famously has no income or sales tax, it relies very heavily on property taxes. About 65 percent of government revenues come from property taxes – the highest dependence on such levies in the U.S.)

By the way, eight of the ten states most dependent on federal money are GOPQ-dominated and seven of the nine states that send more to the Feds than they receive are Democrat-dominated. But maybe that will change as people move around.

At least it’s ‘systematic’

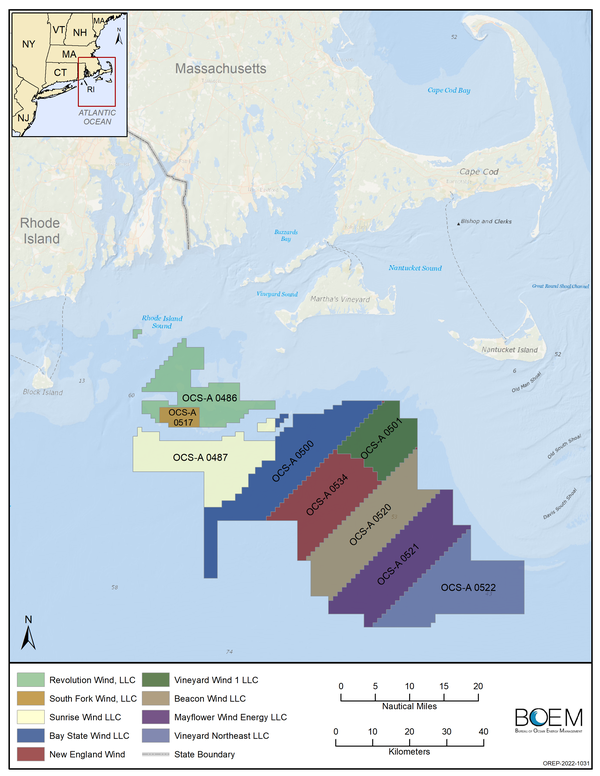

The corrupt and highly entertaining James Michael Curley (1874-1958), who in his terms as Boston’s mayor skillfully appealed to the resentments of city’s Irish-American residents about the “Boston Brahmin” WASP elite. He was the basis of Edwin’s O’Connor’s great novel The Last Hurrah.

Editor’s note: My paternal grandfather first met Curley in 1930, when they had a conversation of about 10 minutes. He next encountered him in 1949. Curley asked after my grandmother and her two children by name and other related family stuff. Like most great pols, he had a capacious memory for personal information about current and potential voters.

“Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds, and Massachusetts politics had been as harsh as the climate. The chief charm of New England was harshness of contrasts and extremes of sensibility —a cold that froze the blood, and a heat that boiled it —so that the. pleasure of hating—oneself if no better victim offered —was not its rarest amusement; but the charm was a true and natural child of the soil, not a cultivated weed of the ancients. The violence of the contrast was real and made the strongest motive of education. The double exterior nature gave life its relative values. Winter and summer, cold and heat, town and country, force and freedom, marked two modes of life and thought, balanced like lobes of the brain. Town was winter confinement, school, rule, discipline; straight, gloomy streets, piled with six feet of snow in the middle; frosts that made the snow sing under wheels or runners; thaws when the streets became dangerous to cross; society of uncles, aunts and cousins who expected children to behave themselves, and who were not always gratified; above all else, winter represented the desire to escape and go free. Town was restraint, law, unity. Country, only seven miles away, was liberty, diversity, outlawry, the endless delight of mere sense impressions given by nature for nothing, and breathed by boys without knowing it.’’

Henry Adams (1838-1918), in The Education of Henry Adams (1918). He was a member of the famous Boston] area-based Adams political family that started with President John Adams.

Mass. promoting addiction; best place to live?

Odds boards in a Las Vegas facility

— Photo by Baishampayan Ghose

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Much of sports beyond the high-school level is becoming an adjunct of the huge sports-betting industry, which continues to create ever more gambling addicts. Massachusetts is doing its part to make things worse by now allowing – actually, encouraging -- sports betting in order to get more tax revenue – instant gratification on whatever electronic device you want.

The release of dopamine during gambling occurs in brain areas similar to those activated by taking certain widely abused drugs. Similar to drugs, repeated exposure to gambling and its associated uncertainty and anxiety, as well as its happy rush, produces lasting changes in the human brain.

Remember that betting is rife among poor people.

So state government will inevitably cause another increase in the social ills associated with addictive gambling – substance abuse, bankruptcies, embezzlements, etc.

Bettable?

A portion of the gorgeous Connecticut River Valley in South Deerfield, Mass.

— Photo by Tom Walsh

WalletHub has declared Massachusetts the best state to live in, based on affordability, the economy, education and health, quality of life and safety.

Rhode Island, a much poorer state, was way down at 28th, and Connecticut, with its troubled cities, a mediocre 25th. But New Hampshire was 6th, Maine was 11th and Vermont 12th. Those are known for their calm, civic-minded cultures and, yes, relatively homogeneous populations.

Interestingly, two other states with large urban populations and high taxes, like the Bay State, ranked high– New Jersey 2nd and New York 3rd.

The central factor: Good public services and the willingness to pay for them. The worst states to live in, as usual Trump cult states. Suckers!

But as always, take all such rankings with skepticism. Comparing apples with oranges, etc.

To read the whole list, hit this link.

Could lineless lobstering help save North Atlantic Right Whales from extinction?

North Atlantic Right Whale mother and calf.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A group of Massachusetts lobstermen may have a way to be allowed to resume fishing in areas that have been closed off to such fishing because the vertical lines to traps (aka “pots”) at the sea bottom can entangle, injure and kill North Atlantic Right Whales and other whales, too.

The group would use remotely controlled balloon-like devices to bring the traps to the surface without lines. I wouldn’t be surprised if regulators mandate such arrangements, though naturally some other lobstermen are angry about the potential high expense.

Besides the fact that whales are big, highly intelligent, “charismatic” fellow mammals, why should we care if they go extinct? It’s because all species are connected. If you kill off one species, it has a knock-on and usually damaging (even lethal) effect on some others. The “web of life” and all that.

Old-fashioned lobster pot.

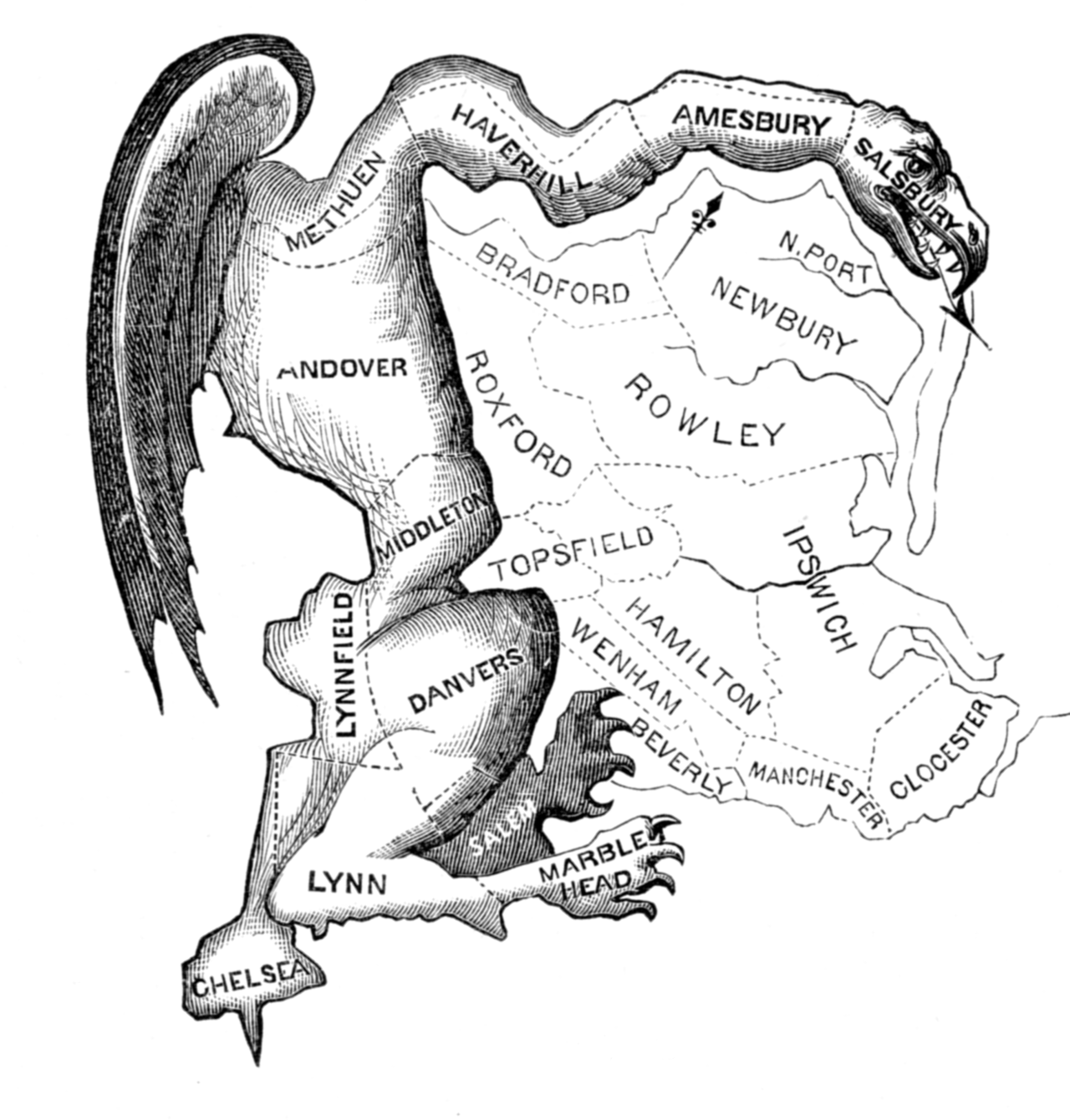

Ruthless political amphibian

Printed in March 1812, this political cartoon was made in reaction to the newly drawn state senate election district of South Essex created by the Massachusetts legislature to favor the Democratic-Republican Party. The caricature satirizes the bizarre shape of the district as a dragon-like "monster," and Federalist newspaper editors and others at the time likened it to a salamander.

The term gerrymander is named after Elbridge Gerry, the Massachusetts governor (and later U.S. vice president) who in 1811 signed a bill creating the district above. Gerrymandering is almost always considered a corruption of the democratic process.

— Jeffrey Toobin (born 1960), American lawyer and journalist, including as a CNN legal analyst.

‘Great equality’ in Mass. in 1789

Samuel Lincoln House, in Hingham, Mass., built on land purchased in 1649 by Samuel Lincoln, an ancestor of Abraham Lincoln

" There is a great equality in the people of this state.

Few or no opulent men, no poor. Great similitude in their buildings, the general fashion of which is a chimney (always of brick or stone), and door in the middle, with a staircase fronting the latter; two flush stories with a very good show of sash and glass windows; the size generally from 30 to 50 feet in length, and from 20 to 30 in width, exclusive of back shed, which seems to be added as the family increases.’’

— George Washington, in his journal of his tour of Massachusetts in 1789

Amazon to hire 1,500 workers in Mass. to deal with holiday crush

“Battle of the Amazons (1618), ‘‘by Peter Paul Rubens

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Amazon recently announced that it plans to hire 1,500 seasonal workers in Massachusetts to help meet the holiday demands. This is a part of an effort to hire 150,000 seasonal workers around the country.

“Caitlyn McLaughlin, a spokesperson for Amazon, confirmed the announcement while reiterating that the supply-chain challenges that are being experienced will affect consumers around the world. ‘Everyone at Amazon is working to anticipate and prepare for various scenarios to ensure positive delivery experiences this holiday season, for instance, by launching promotions to encourage earlier shopping,’ said McLaughlin.

“Amazon is one of Massachusetts five largest employers, according to the Business Journal, and covers both the tech industry and the retail industry. Over this past summer the company had 20,000 positions available in the state for both part time and full-time positions in both industries.’’

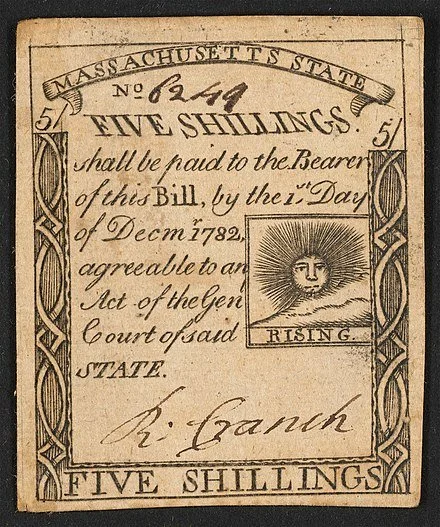

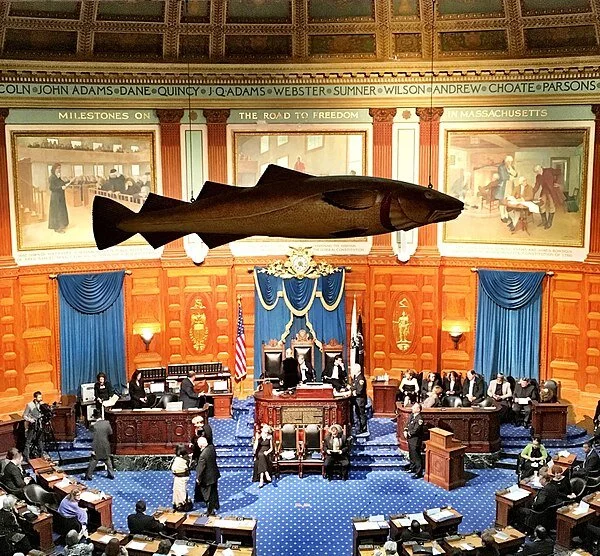

Cod helped build New England

“The Sacred Cod” hangs above the Massachusetts House of Representatives chamber as a symbol of the fish’s historical importance to the prosperity of the state.

“By 1937, every British trawler had a wireless, electricity, and an echometer - the forerunner of sonar. If getting into fishing had required the kind of capital in past centuries that it cost in the twentieth century, cod would never have built a nation of middle-class, self-made entrepreneurs in New England.”

― From Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, by Mark Kurlansky

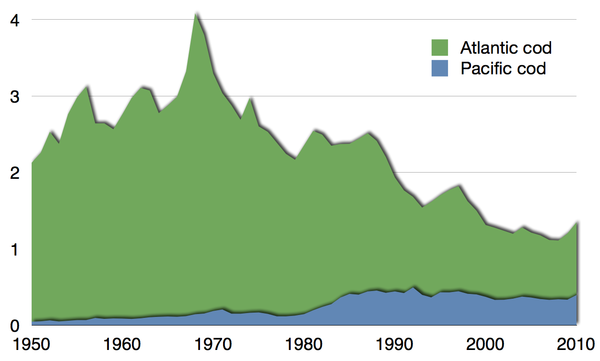

Showing embedded in light green the collapse of the northwest Atlantic cod fishery

In the 19th Century, banks dories were carried aboard larger fishing schooners, and used for handlining cod on the Grand Banks and Georges Bank.

‘Even in Massachusetts’

“The Dance Class,’’ by Edgar Degas, 1874

“The average parent may, for example, plant an artist or fertilize a ballet dancer and end up with a certified public accountant. We cannot train children along chicken wire to make them grow in the right direction. Tying them to stakes is frowned up, even in Massachusetts.’’

— Ellen Goodman (born in 1941), Boston Globe columnist.

Calm down, old boy!

The north-central Pioneer Valley in South Deerfield, Mass.

— Photo by Tom Walsh

“Massachusetts! A word surrounded with an aura of hope! A state with a soul! There is gathered up into her name the brilliant program of a new world.’’

— Wallace Nutting, in Massachusetts Beautiful (1923)

Built in 1681, the Old Ship Church, in Hingham, Mass., is the oldest church in America in continuous ecclesiastical use. Massachusetts has since become one of the most irreligious states in the U.S. It was built by Puritans, then was Congregational and now is Unitarian-Universalist.

'The amount of maniacs'

Doyle's Cafe, in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. It’s a well-known watering hole.

— Photo by John Phelan

"It’s just a really interesting place to grow up. The sports teams, the colleges, the racial tension, the state workers, the boozing, the anger. All of that stuff. I don’t think I ever appreciated the amount of maniacs that live in Massachusetts until I left. When I lived here, I took it for granted that everyone was kind of funny and a bit of a character."

— Bill Burr (born in 1968), stand-up comedian who grew up in the inner Boston suburb of Canton

Rachel Bluth: After a year of motorized mayhem, Mass., Conn., R.I., other states consider crackdowns

“American Landscape’’ (graphite on Strathmore rag, 1974), by Jan A. Nelson

See news on this topic from Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut below.

As more Americans start commuting to work and hitting the roads after a year indoors, they’ll be returning to streets that have gotten deadlier.

Last year, an estimated 42,000 people died in motor-vehicle crashes and 4.8 million were injured. That represents a 8 percent rise from 2019, the largest year-over-year increase in nearly a century — even though the number of miles driven fell by 13 percent, according to the National Safety Council.

The emptier roads led to more speeding, which led to more fatalities, said Leah Shahum, executive director of the Vision Zero Network, a nonprofit organization that works on reducing traffic deaths. Ironically, congested traffic, the bane of car commuters everywhere, had been keeping people safer before the pandemic, Shahum said.

“This is a nationwide public health crisis,” said Laura Friedman, a California Assembly member who introduced a bill this year to reduce speed limits. “If we had 42,000 people dying every year in plane crashes, we would do a lot more about it, and yet we seem to have accepted this as collateral damage.”

California and other states are grappling with how to reduce traffic deaths, a problem that has worsened over the past 10 years but gained urgency since the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. Lawmakers from coast to coast have introduced dozens of bills to lower speed limits, set up speed camera programs and promote pedestrian safety.

The proposals reflect shifting perspectives on how to manage traffic. Increasingly, transportation safety advocates and traffic engineers are calling for roads that get drivers where they’re going safely rather than as fast as possible.

Lawmakers are listening, though it’s too soon to tell which of the bills across the country will eventually become law, said Douglas Shinkle, who directs the transportation program at the National Conference of State Legislatures. But some trends are starting to emerge.

Some states want to boost the authority of localities to regulate traffic in their communities, such as giving cities and counties more control over speed limits, as legislators have proposed in Michigan, Nebraska and other states. Some want to let communities use speed cameras, which is under consideration in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Florida and elsewhere.

Connecticut is considering a pedestrian safety bill that incorporates multiple concepts, including giving localities greater authority to lower speeds, and letting some municipalities test speed cameras around schools, hospitals and work zones.

“For decades really we’ve been building roads and highways that are suitable and somewhat safe for motorists,” said Connecticut state Sen. Will Haskell (D.-Westport), who chairs the committee overseeing the bill. “We also have to recognize that some people in the state don’t own a car, and they have a right to move safely throughout their community.”

A huge jump in road fatalities started showing up in the data “almost immediately” after the start of the pandemic, despite lockdown orders that kept people home and reduced the number of drivers on the road, said Tara Leystra, the National Safety Council’s state government affairs manager.

“A lot of states are trying to give more flexibility to local communities so they can lower their speed limits,” Leystra said. “It’s a trend that started before the pandemic, but I think it really accelerated this year.”

In California, citations issued by the state highway patrol for speeding over 100 miles per hour roughly doubled to 31,600 during the pandemic’s first year.

Friedman, a Democrat from Burbank, wants to reform how California sets speed limits on local roads.

California uses something called the “85th percentile” method, a decades-old federal standard many states are trying to move away from. Every 10 years, state engineers survey a stretch of road to see how fast people are driving. Then they base the speed limit on the 85th percentile of that speed, or how fast 85% of drivers are going.

That encourages “speed creep,” said Friedman, who chairs the state Assembly’s transportation committee. “Every time a survey is done, a lot of cities are forced to raise speed limits because people are driving faster and faster and faster,” she said.

Even before the pandemic, a California task force had recommended letting cities have more flexibility to set their speed limits, and a federal report found the 85th percentile rule similarly inadequate to set speeds. But opposition to the rule is not universal. In New Jersey, for instance, lawmakers introduced a bill this legislative session to start using it.

Friedman’s bill, AB 43, would allow local authorities to set some speed limits without using the 85th percentile method. It would require traffic surveyors to consider areas like work zones, schools and senior centers, where vulnerable people may be using the road, when setting speed limits.

In addition to lowering speed limits, lawmakers also want to better enforce them. In California, two bills would reverse the state’s ban on automated speed enforcement by allowing cities to start speed camera pilot programs in places like work zones, on particularly dangerous streets and around schools.

But after a year of intense scrutiny on equity — both in public health and in law enforcement — lawmakers acknowledge they need to strike a delicate balance between protecting at-risk communities and overpolicing them.

Though speed cameras don’t discriminate by skin color, bias can still enter the equation: Wealthier areas frequently have narrow streets and walkable sidewalks, while lower-income ones are often crisscrossed by freeways. Putting cameras only on the most dangerous streets could mean they end up mostly in low-income areas, Shahum said.

“It tracks right back to street design,” she said. “Over and over again, these have been neighborhoods that have been underinvested in.”

Assembly member David Chiu (D.-San Francisco), author of one of the bills, said the measure includes safeguards to make the speed camera program fair. It would cap fees at $125, with a sliding scale for low-income drivers, and make violations civil offenses, not criminal.

“We know something has to be done, because traditional policing on speed has not succeeded,” Chiu said. “At the same time, it’s well documented that drivers of color are much more likely to be pulled over.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Grace Kelly: Floating turbines may be part of New England offshore-wind network

Floating turbines come in various styles.

— Joshua Bauer/U.S. Department of Energy

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The winds and airs currents swirling around the oceans of this blue marble have the potential to power our cities and towns. And locally in coastal New England, the race to harness the power of coastal wind has been accelerating.

Last year then-Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order that called for an ambitious, yet somewhat vague, “100 percent renewable energy future for Rhode Island by 2030” — a good portion of which would be from offshore wind.

“There is no offshore wind industry in America except right here in Rhode Island,” Raimondo said at the time. She was referring to the groundbreaking five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm, a 30-megawatt project that was the first commercial offshore wind facility in the United States.

Today, there is a slightly different picture forming, and other New England states, notably Massachusetts and Maine, are looking into becoming a part of a regional offshore wind network.

During a March 18 online presentation, Environment America discussed a recently released report detailing the overall potential that offshore wind has, specifically in New England. The discussion also included presentations from experts in the field of offshore wind.

“We found that the U.S. has a technical potential to produce more than 7,200 terawatt-hours of electricity in offshore wind,” said Hannah Read of Environment America, a federation of state-based environmental advocacy organizations. “What we did was we compared that to both our electricity used in 2019 and the potential electricity used in 2050, assuming that we transition society to run mostly on electric rather than fossil fuels, and what we found is that offshore wind could power our 2019 electricity almost two times over, and in 2050 could power 9 percent of our electricity needs.”

On a more granular level, Read said Massachusetts has the highest potential for offshore-wind-generation capacity, and Maine has the highest ratio of potential-generation capacity relative to the amount of electricity that it uses.

Massachusetts is entering the final stages of the federal permitting process for the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project, which is slated to start construction next year and go online in 2023.

“We have some real frontrunners here in New England and we have a huge opportunity to take advantage of this resource,” Read said. “When you look at the New England as a region, it could generate more than five times its projected 2050 electricity demand.”

While Rhode Island and Massachusetts are looking to more traditional fixed-bottom turbines, in coastal Maine, where coastal waters are deeper, researchers at the University of Maine are testing prototypes for floating wind turbines.

“The state of Maine has deep waters off its coasts. If you go three nautical miles off the coast … you’re in about 300 feet of water,” said Habib Dagher, founding executive director of the Advanced Structures & Composites Center at the University of Maine. “Therefore, you can’t really use fixed-bottom turbines.”

To mitigate this, Dagher and his team have been building and testing floating turbines for the past 13 years, using technology from an unlikely source.

“There are three different categories of floating turbines and ironically enough we have the oil and gas industry to thank for developing floating structures,” Dagher said. “We borrowed these designs … and adapted them to floating turbines.”

Many of these floating turbines rely on mooring lines and drag anchors to keep them from floating away, and they come in various styles.

Dagher noted that while other states are able to pile-drive turbines, they should consider floating turbines as another way to fit more wind power into select offshore areas that could become crammed full.

“We’re going to run out of space to put fixed-bottom turbines. We have to start looking at floating … on the Massachusetts coast and beyond, in the rest of the Northeast,” he said.

Shilo Felton, a field manager for the Audubon Society’s Clean Energy Initiative, addressed another issue facing offshore wind: bird migration patterns. Focusing on the northern gannet, a large seabird, she explained that while climate change itself is negatively affecting bird populations, it is important to take care that offshore wind doesn’t make the situation worse.

She noted that Northern Gannets experience both direct and indirect risks from offshore wind. “Direct risks are things like collision, indirect risks are things like habitat loss,” Felton said.

But Felton also acknowledged that since we don’t really have lots of large-scale wind projects in the United States currently, it’s hard to really say how much those risks will impact bird populations.

“We don’t have any utility-scale projects yet, so we don’t really know how the build out in the United States is going to impact species,” she said. “So that requires us to take this adaptive management approach where we monitor impacts as we build out so that we can understand what those impacts are.”

Overall, the potential that offshore wind holds as a viable mitigation tactic in the fight to curb and eventually eradicate greenhouse-gas emissions is great. But, as speakers noted, implementation has to be done thoughtfully and thoroughly.

Referring specifically to Maine, Dagher said, “The state is moving on to do a smaller project of 10 to 12 turbines, and that would help us crawl before we walk, walk before we run. Start with one, then put in 10 to 12 and learn the ecological impacts, learn how to work with fisheries, learn how to better site these things before we go out and do bigger projects in the future.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News journalist.

Closing on final approval of Vineyard Wind 1

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Avangrid recently received the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for Vineyard Wind 1 from the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the last step before a Record of Decision (ROD) that would jumpstart approval for the project to begin construction.

“A joint venture between Avangrid Renewables and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), Vineyard Wind seeks to establish a massive offshore wind farm about 15 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard.“Dennis V. Arriola, CEO of Avangrid, commented, “We are one step closer toward realizing this historic clean energy project and delivering cost-effective clean energy, thousands of jobs and more than a billion dollars in economic benefits to Massachusetts.” The project would generate electricity to power over 400,000 residences and businesses in Massachusetts, while also reducing electricity rates, carbon emissions, and creating new job opportunities.

“The New England Council looks forward to the progress Avangrid makes in developing this project for the region. Read more from the Hartford Business Journal and Avangrid’s press release.’’