David Warsh: Keynes and Freud

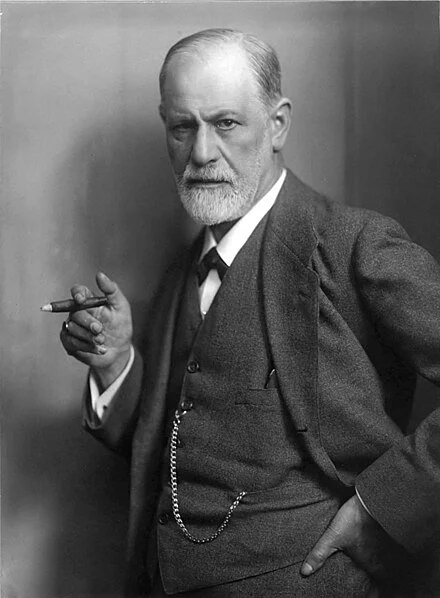

Sigmund Freud in 1921. His cigar addiction gave him oral cancer, which led to his death in London in 1939. He had fled there to escape the Nazis, after Hitler’s Germany had taken over Freud’s native Austria.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column has become interested in the difference of opinion between John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman with respect to their explanations for the causes of the Great Depression, Keynes blamed social aggregates within the economy itself for a sudden fall, Friedman blamed an inept Federal Reserve. History has shown that Friedman was right and Keynes wrong.

Last week I likened both men to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a split personality from the famous novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. The comparison seemed apt for Friedman, insofar as in contrast to the relative precision of his theorizing, the policies he recommended as a cultural entrepreneur, especially in Capitalism and Freedom, routinely departed from those I consider sensible. Alec Cairncross put the case for economic realism well in an address on the two hundredth anniversary of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

The Jekyll/Hyde comparison seemed to work relatively well in Friedman’s case. Abolish Social Security? Stop licensing the professions beginning with physicians? Get rid of national health insurance? Hog-tie the Fed in crises? “Starve the beast” of government by cutting taxes to the bone? Come on, Mr. Hyde!

The comparison did not, however, suit Keynes . Even the excesses of “The End of Laissez Faire” stopped short of murdering his darlings. The challenge was to come up with a metaphor for Keynes that seemed to work.

Let’s try Sigmund Freud on for size.

Both men were born in the 19th Century, Freud in 1869, Keynes in 1883. Both came of age in a time of great excitement about the possibilities of new sciences. The Interpretation of Dreams appeared in 1905 and The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936.

Both men wrote extremely well, both sought to overturn substantial portions of the received wisdom of their respective fields, Keynes with an intuitive vision of macroeconomics (a term late supplied by Ragnar Frisch), Freud with psychoanalysis. Both depended on influential discussion groups to advance their views. Both achieved enormous influence on culture in their day. Both inspired celebrated biographies.

The economist was well acquainted with Freud’s work. Keynes told a friend he was reading through all Freud’s books. He wrote a letter to a magazine calling the psychoanalyst “one of the great, disturbing geniuses of our time.” I found no evidence that Freud read Keynes, but he didn’t look very far. Freud died in 1939, Keynes in 1946. Subsequent critics, mostly from the analytic community, have argued that Keynes’s view of human nature was very similar to that of Freud.

But the real similarity between the two scientists/latter-day culture entrepreneurs has to do with the posthumous influence of their work. Freud’s reputation as a successful scientific revolutionary and culture entrepreneur has been steadily diminished by advances in other branches of psychology, neurology and diagnostics.

Within technical economics. Keynes’s authority began to ebb in the ‘70’s Clarified an refined by generations of system builders, incorporated in formal models, “neo-Keynesian” views remain widespread. But macroeconomics is in flux today, and there is no way of telling how, in 20 or 30 years, Keynes’a contribution will be viewed.

This much seems likely: because he wrote so well, Keynes’s reputation in the humanities, like that of Freud, will prove to be imperishable.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: The split records of Keynes and Friedman

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning I have been convinced that Milton Friedman possessed a dual personality, somewhat like Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde: a strong economist by day, a weak citizen by night. Nothing I’ve read and written about in the last nine weeks has convinced me otherwise, not even Edward Nelson’s meticulous explication ofFriedman’s professional life from 1929 to 1972.

Instead, my suspicions have grown with the passage of time that with John Maynard Keynes, it was the other way around. What if Keynes was a weak technical economist, but a strong citizen by night? Turning things on their heads after seventy-five years requires time, a critical biography by a first-rate economist in the future, and, in my case, not much more than cheek. I’ll sketch the bare bones of the argument here, and hope to return to it someday.

This puts me up against the judgment of Nelson and, worse, of Friedman himself. In Newsweek magazine, in 1970, he wrote:

“Now John Maynard Keynes was one of the greatest economists of all time. I know many people who regard him as a devil who brought all sorts of evil things into this world – he was not that; he was like rest of us; he made mistakes. He was a great man, so when he made mistakes, they were great mistakes. But he was a great man.”

But I am a journalist, not an economist, and it’s the mistakes that interest me, one of them in particular: his diagnosis of the causes of the Great Depression. Keynes regarded it as, like any recession, a drop in aggregate demand, moving economic output below the production capacity of the economy. In such circumstances, he argued, governments should counter recessions through an expansionary fiscal policy that boosts aggregate demand.

Friedman and his research partner Anna Schwartz advanced a different explanation of the Great Depression in their A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. Ben Bernanke, a leading scholar of the decade of the 1930s, before he became a central banker, summarized their argument this way: “central bankers’ outmoded doctrines and flawed understanding of the economy had played a crucial role in that catastrophic decade, demonstrating the power of ideas to shape events.”

In 2007-08. Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke, with the help of many others, forcefully demonstrated the power of better ideas. Together, they saved the world from a Second Great Depression.

Keynes may have had many brilliant ideas as an economist, but his single greatest success came as a journalist. The Economic Consequences of the Peace, his 1919 book, fiercely criticized the harsh reparations demanded of Germany in the wake of World War I, correctly foresaw the causes of World War II, and supplied the foundations of the 1947 Marshall Plan, aimed at the reconstruction of Germany, not punishment for its many sins.

My friend, Peter Renz like me, a non-economist, described the essence of Keynes this way: “a romantic figure. A polymath, brilliant as a writer, alive with charm as a lover, witty, political, a man of business and action.”

In this view, Keynes, born in 1883, was the last eminent Victorian of a certain sort. He was not included in that volume of portraits written by Keynes’s friend Lytton Strachey. Perhaps he, along with Friedman, will appear in a volume by some latter-day Strachey. (The figment of my imagination is the tenth good book). Meanwhile, I can’t do better than Wikipedia’s summary of the original:

“Eminent Victorians is a book by Lytton Strachey (one of the older members of the Bloomsbury Group), first published in 1918, and consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era. Its fame rests on the irreverence and wit Strachey brought to bear on three men and a woman who had, until then, been regarded as heroes: Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold and Gen. Charles Gordon. While Nightingale is actually praised and her reputation enhanced, the book shows its other subjects in a less-than-flattering light, for instance, the intrigues of Cardinal Manning against Cardinal Newman.”

And Friedman? He had two great successes as an economist. One of them should be clear by now. That single chapter of the Monetary History makes engrossing reading. It has its flaws – the significance it assigns to the 1930 failure of the grandly named Bank of the United States, a hastily assembled commercial bank in New York City, chartered in 1913, seems overblown – but overall, Friedman’s and Schwartz’s analytic narrative of the series of banking panics that unfolded 1930-33 is convincing.

Friedman’s other achievement is more diffuse but more important. He brought monetary analysis back into the big tent of economics that that had been dominated for more than a century by analysis of “real” goods and services by the forces of supply and demand. I keep on the shelf above my desk two little Cambridge Handbooks of 1922, Supply and Demand, by H. D. Henderson, and Money, by D. H. Robertson.

That was the situation before Keynes. In his General Theory, he sought to unite them, but the makers of macroeconomics who followed him somehow have failed to come up with an account of a business cycle without periodic financial crises.

“Monetarism,” a slogan that Friedman is said to have disliked, as opposed to “monetary theory,” doesn’t do much better, but at least it puts central banks back in the the story. As for rules as an alternative to occasional discretion, as a means of deflecting the occasional crisis? I doubt it.

And Friedman’s dark side? Nothing worse than being the most prominent spokesman for an exaggerated version of the common failing of today’s economics – its emphasis on the role of the individual, at the expense of attention to his/her/their entanglement in society (in Herbert Gintis’s phrase). British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously proclaimed “There’s no such thing as society.” That’s bunk, even worse than macro without crises.

At least the tale of Jekyll and Hyde is the story one journalist has to tell.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Why did Paul Samuelson end his momentous debate with Milton Friedman?

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a transformative national debate, on the level of Hamilton and Jefferson, or Lincoln and Douglas: Paul Samuelson (1915-2009) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Milton Friedman (1912-2006) of the University of Chicago, wrote dueling columns for Newsweek magazine from 1966 until May 1984. Then their arrangement ended abruptly, With no public explanation, Samuelson quit.

Why?

Friedman had become well known as a critic of government spending on basic research. In Free to Choose, the 1980 book accompanying their highly successful television series, he and his economist wife, Rose, had argued that the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and tax subsidies to higher education are undesirable and should be abolished.

Since Friedman was also an adviser to future President-elect Ronald Reagan, reporter Nicholas Wade, of Science magazine, called him up to ask what should be put in their place?

“Nothing,” Friedman replied. “The Treasury, the citizenry and the advancement of science would all be better off without the NSF and other research agencies.”

In his interview, Friedman enumerated to Wade the problems he felt that government caused. They boiled down to mediocrity, waste, abuse and a chilling effect on the academic community’s willingness to speak frankly and criticize programs. Harvard philosopher Willard Quine had made much the same argument in an essay in Daedalus in 1974.

Wade asked Friedman on whom should the burden of proof be placed?

“On those who wish to extract money from below-income taxpayer, or on those who argue the other way. I challenge you to find a single study justifying the amount of money now being spent on government support for research science.”

Abolition of government funding had been no proposal to advance in 1980, Friedman admitted, when Reagan was no more proven a candidate than had been Barry Goldwater, whom Friedman had also advised, in 1964. But it was now 1981, and Reagan was at the newly elected president, riding a wave of excitement. When Friedman repeated his arguments in Newsweek in May, Paul Samuelson never wrote for the magazine again.

Some background: Samuelson had attended Harvard University on one of the first Social Science Research Council fellowship, leaving for MIT in 1940. In the late stage of World War II, the 29-year-old Samuelson had served, with John Edsall, the biochemist, and Robert Morison, head of biology for Rockefeller Foundation, on a subcommittee established to study post-war science policy for Vannevar Bush, World War II science czar.

When Bush’s report, Science, The Endless Frontier, was issued, in 1945, it contained the recommendations that the trio had favored: Pentagon funding for military technology; the National Institute of Health, for medicine; and National Science Foundation, for basic and applied science (including social sciences). Not until 1958, after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik , its first satellite, the year before, was the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was established.

Five years had been required to establish the NSF, owing to opposition in Congress, from populist senators who wanted funding to be distributed, equally among the states, county by county, pork-barrel fashion, rather than by a system of peer review. At the other end of end of the argument was Polaroid’s Edwin Land, who felt that government should favor entrepreneurial inventors, such as today Silicon Valley s titans (and, in those days, himself).

Fifteen years later, I asked Samuelson whether there had been any connection between one event and the other. Had he suffered enough of his rival? Not at all, Samuelson replied. He had been about quitting after a copy editor had changed a headline on a prior column in a way that displeased him.

Somehow, I didn’t believe him. I raised an eyebrow, and we continued the interview.

I thought of that when I took down from the shelf Better Living through Economics (Harvard, 2011 ), a book edited by John Siegfried, that I hadn’t found a way to write about when it was published. The title was a play on a famous Dupont Co. advertising campaign, “Better living through chemistry.” Multiple chickens and multiple pots graced the book’s jacket, a reference to Herbert Hoover’s 1928 campaign promise, “a chicken in every pot.’’ Siegfried, a Vanderbilt University professor, had been for many years the widely respected secretary-treasurer of the American Economic Association.

The book contained a dozen case studies by leading economists who had been involved in policy reforms, followed by expert commentary on each. Siegfried noted in an introduction that only one of the studies, the all-volunteer armed force, had been pursued by academic economists without external funding. Eventually Richard Nixon appointed a presidential commission to study transition from conscription to a market-based military; many economists were involved in its work. The plan they came up with was implemented in 1973.

In an overview of the essay, Charles Plott, of Caltech, noted that the contributions of economics had been accomplished “with only a tiny fraction of the level of research support given to other sciences.” Yet basic and applied research in economics, he asserted, had profound effects on American life.

The 12 essays included in Better Living through Economics described emissions trading; improved price indices; the effects of trade liberalization on growth in developing nations; welfare-to-work reform; a revolution in monetary economics; adoption of electro-magnetic spectrum auctions; air-transport deregulation; the application of deferred acceptance algorithms in school choice and medical education; new anti-trust measures; all-volunteer military forces, and policies to encourage retirement savings.

Regardless of whether you consider the effects of all these measures to have been net beneficial, you may agree that each was worth a try. Some clearly worked to provide better living. Perhaps others didn’t succeed as well. After two or three American wars, for example, the returns on an all-volunteer-military force vs. conscription are not in.

One other test of government-sponsored basic research is worth thinking about, however – a natural experiment in which virtually all Americans took part. This experiment was conducted without any of the protocols that Milton Friedman demanded as proof of the value of at least some, if not all, government spending on basic research. Certainly it can be argued about, long after the fact. But scale alone makes it important.

More on that experiment next week.

xxx

The reason that Samuelson gave for his decision to quit his long-standing column stemmed from the magazine’s decision to spike without telling him the column he had turned in, about John Kenneth Galbraith’s memoirs. Newsweek had reviewed the book “rather thoroughly” three weeks before, the editor explained.

Is it possible that Samuelson seized on the magazine’s slight as a fig leaf to conceal his irritation at Friedman’s proposal? The week before, the Chicagoan had called on the Reagan administration to sharply cut back on National Science Foundation’s grants to economists? Perhaps. In matters requiring diplomacy, the MIT professor was an artful dodger. But Samuelson turned 65 that year. He’d been dueling with Friedman in Newsweek since 1966.

Whatever the case, it was an abrupt way to end a momentous public debate.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, a proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: 'The Economists' Hour' and its hangover

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Books like The Economists’ Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets and the Fracture of Society (Little Brown, 2019), by Binyamin Appelbaum, of The New York Times, don’t come along very often. Tyler Cowen, the peripatetic George Mason University professor, says he read the whole thing in one sitting. It took me three days, but the impulse was the same. I picked it up every chance I got. When I had finished, I read its 90 pages of endnotes one after another, as if it were a second book, only slightly less interesting than the first.

Why? Well, Appelbaum is a careful reporter, a graceful writer, and a first-rate story-teller. He joined The Times’s Washington bureau in 2010 from The Washington Post, and, before that, The Boston Globe, and the Charlotte Observer, to cover monetary policy in the aftermath of the financial crisis. In the book he covers a much broader spectrum of policy developments. He did a good deal of first hand reporting, ingested a huge amount of secondary literature, and did some archival work himself. Mainly, though, I was impressed by his skill as a listener. He possesses a special gift for capsule biography.

Of necessity, the storyteller gets the upper hand. Appelbaum writes:

In the four decades between 1969 and 2008, a period I call ‘‘the Economists’ Hour,” borrowing the phrase from the historian Thomas McCraw, economists played a leading role in curbing taxation and public spending, deregulating large sectors of the economy, and clearing the way for globalization. Economists persuaded President Nixon to end military conscription. Economists persuaded the federal judiciary largely to abandon the enforcement of the antitrust laws. Economists even persuaded the government to assign a dollar value to human life – around $10 million in 2019 – to determine whether regulations were worthwhile.

Such a “biography” of a “trust-in-markets” revolution needs a central character, and Appelbaum chose his well. His subject is Milton Friedman, who concentrated on research in the first half of his career and became a public intellectual in the second half. In Capitalism and Freedom, which appeared in 1962, Friedman advocated most of the nostrums that were adopted in one degree or another in the coming decades: floating exchange rates instead of fixed one, an all-volunteer army instead of one based on conscription, draconian tax reductions, charter schools, industrial deregulation, shareholder hegemony in public corporations, and one measure that didn’t eventuate – a guaranteed annual income for all citizens, replacing the Social Security retirement system.

In fact all this was a counterrevolution, Appelbaum knows it, and says as much at several points in his story. But he was born in 1978. He wasn’t there during the four decades that ended in 1969: the New Deal; the Keynesian revolution; the economists’ triumph as architects of World War II logistics; the Marshall Plan; the “new economics” of the Sixties; and the record-breaking post-war boom of the industrial democracies.

This rise of the “modern mixed economy” after 1933 was viewed at the time as an alternative to the top-down government control that characterized Soviet and Chinese communism. It had plenty of dynamism, but retained enough of the communitarian ethos of wartime (such as fixed exchange rates under the Bretton Woods Agreement) as to seem, by the late 1960s, more than a little confining. Appelbaum knows all this because he has read widely; he even cites Tony Judt, the leading historian of the postwar decades, in an endnote. But, like many others, he gives short shrift to the period before his own.

Instead, he starts with something we all know, the Vietnam War. A brilliant first chapter traces the evolution of a plan for an all-volunteer army from a chance dinner-party conversation between economic professor Martin Anderson and a law partner of Richard Nixon, through its gradual adoption by Nixon 1968 presidential campaign, and its design by University of Rochester economist Walter Oi, to its eventual adoption under the guidance of economist George Shultz, then director of the Office of Management and Budget. A little extra time to end the war had been purchased. The basic inequity of conscription had been solved. A market for soldiering had been established. But, writes Appelbaum, “War, once an abnormal act of national purpose, has become a regular line of work.”

Appelbaum then works his way through chapters on inflation, taxation, antitrust enforcement, deregulation, cost-benefit analysis, exchange-rate regimes, globalization, and banking. any one of which could warrant an entire book. These are successively less satisfying. He is forced to take shortcuts: Robert Mundell wasn’t a baby-faced hero; antitrust enforcement isn’t dead; the story of Venezuela is as interesting as the very different one of Chile. But such are his skills as a storyteller that, by the time he introduces Albert Hirschman, author of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, in the book’s final pages, Appelbaum’s central point has become indelibly clear: “[T]he defining feature of a market is the freedom to walk away.”

Appelbaum writes, “Friedman chose to see the role of individual initiative rather than the context of public support. He celebrated drivers and took roads for granted.” That’s very apt, as far as it goes. And in the end even he gets a sensitive hearing: “Friedman had as large a hand in the [2008] crisis as any man, but it is a mark of the complexity of his legacy that he also left effective instructions for limiting the damage.”

The problem is that plenty of economists have continued to celebrate roads during the last 40 years – as well as government-sponsored retirement systems, health insurance, unemployment insurance, capital budgets, trade agreements, counter-cyclical spending, environmental protection, and, in general, social and cultural entrepreneurship.

For a more balanced view of the stance of the economics profession towards society, you might read The Vital Few: The Entrepreneur and American Economic Progress (1986), by economist Jonathan Hughes. It is a highly readable history, couched in much the style Appelbaum has written. Hughes, of course, published his account in the halcyon period before the costs of late-stage globalization became apparent. The Economists’ Hour is a useful guide to those costs. Applebaum writes:

In the pursuit of efficiency, policy makers subsumed the interests of Americans as producers to the interests of Americans as consumers, trading well-paid jobs for low-cost electronics. This, in turn, weakened the fabric of society and the viability of local governance. Communities mitigate the consequences of local job losses; one reason mass layoffs are so painful is that the community, too, often is destroyed. The loss exceeds the sum of its parts.

It wasn’t obvious what would happen when Apple chose to manufacture its smartphones in China; or when IBM sold its laptop business to Lenovo. It was, however, clear enough to corporate executives and their government counterparts what would happen if they didn’t: Chinese companies would inevitably enter the product market themselves and catch up, albeit more slowly than otherwise would have been the case. American policy-makers have been caught flat-footed by the alacrity with which Chinese industry has grown toward the frontiers, and Appelbaum makes much of the ability of Asian nations to carefully manage their economies. But it’s much easier to know what to do when you are following a leader than when you are trying to stay ahead.

What comes after the Economists’ Hour? Appelbaum is clearly focused on inequality, and the extent to which money has gained power beyond its proper sphere. He is 41, and this is his first book. (He is now serving on The Times’s editorial board). It is a sensational debut. Here’s hoping The Times gets him back on the beat, preferably writing the Economic Scene column that Leonard Silk made famous in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Meanwhile, read his book, as a down payment on the next 30 years.

. . xxx

New on the Economic Principals bookshelf:

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream, by Nicholas Lemann (Farrar, Straus)

Free Enterprise: An American History, by Lawrence Glickman (Yale)

Rethinking the Theory of Money. Credit, and Macroeconomics: A New Statement for the Twenty-First Century, by John Smithin (Lexington Books)

Crying the News: A History of America’s Newsboys, by Vincent DiGirolamo (Oxford)

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

David Warsh: Knowledge economy superstars and hollowing of middle class

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is one of the great explications of economics of modern times: Written in 1958 by libertarian Leonard Read and subsequently performed by Milton Friedman as The Pencil, a couple of minutes of Free to Choose, the 10-part television series he made with his economist wife, Rose Director Friedman, broadcast and published in 1980.

Friedman comes alive as he enumerates the various products required to make a simple pencil: the wood (and, of course, the saw that cut down the tree, the steel that made the saw, the iron ore that made the steel and so on), graphite, rubber, paint (“This brass ferrule? I haven’t the slightest idea where it comes from”).

Literally thousands of people cooperated to make this pencil – people who don’t speak the same language, who practice different religions, who might hate one another if they ever met.

This is Friedman as he was experienced by those around him, sparks shooting out of his eyes. The insight itself might as well have been Frederic Bastiat in 1850 explaining the provisioning of Paris, or Adam Smith himself in 1776 writing about the economics of the pin factory.

There is a problem, though. None of these master explicators have so much as word to say about how the pencil comes into being. Nor, for that matter, does most present-day economics, which remains mainly prices and quantities. As Luis Garicano, of the London School of Economics, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, of Princeton University, write in a new article for the seventh edition of the Annual Review of Economics:

Mainstream economic models still abstract from modeling the organizational problem that is necessarily embedded in any production process.Typically these jump directly to the formulation of a production function that depends on total quantities of a pre-determined and inflexible set of inputs.

In other words, economics assumes the pencil. Though this approach is often practical, Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg write, it ignores some very important issues, those surrounding not just the companies that make the products that make pencils, and the pencils themselves, but the terms under which all their employees work, and, ultimately, the societies in which they live.

In “Knowledge-based Hierarchies: Using Organizations to Understand the Economy,” Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg lay out in some detail a prospectus for an organization-based view of economics. The approach, they say, promises to shed new light on many of the most pressing problems of the present day: evolution of wage inequality, the growth and productivity of firms, the gains from trade, the possibilities for economic development, from off-shoring and the formulation of international teams, — and, ultimately, the taxation of all that.

The authors note that, at least since Frank Knight described the role of entrepreneurs, in Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, in 1921, economists have recognized the importance of understanding the organization of work. Nobel laureates Herbert Simon and Kenneth Arrow each tackled the issue of hierarchy. Roy Radner, of Bell Labs and New York University, went further than any other in developing a theory of teams, especially, the authors say, in “The Organization of Decentralized Information Processing,” in 1993.

But all the early theorizing, economic though it may have been in its concern for incentives and information, was done in isolation from analysis of the market itself, according to Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg. The first papers had nothing tp say about the effects of one organization on all the others, or about the implications of the fact that people differ greatly in their skills.

That changed in 1978, the authors say. A decade earlier, legal scholar Henry Manne had noted that a better pianist had higher earnings not only because of his skill; his reputation meant that he played in larger halls. The insight led Manne to conjecture that large corporations existed to allocate the production most efficiently of managers, like so many pianists of different levels of ability.

It was Robert Lucas, of the University of Chicago, who took up the task in 1978 of showing precisely how such “superstar” effects might account for the size of firms, with CEOs of different abilities hiring masses of undifferentiated workers – and why scale might be an important aspect of organization. He succeeded, mainly in the latter, generating fresh interest among economists in the work of business historian Alfred Chandler.

It was Sherwin Rosen, of the University of Chicago, with “The Economics of Superstars,” in 1982, who convincingly made the case that the increasing salaries paid to managers had to do with the increase in scale of the operations over which they preside (and, with athletes, singers and others, the size of the audiences for whom they perform). A good manager might increase the productivity of all workers; the competition among firms to hire the best might cause the winners to build more and larger teams; but Rosen didn’t succeed at building hierarchical levels into his model. He died in 2001, at 62, a few months after he organized the meetings of the American Economic Association as president.

Many others took up the work, including Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg. It was the '90's, not long after a flurry of work on the determinants of economic growth spelled out for the first time in formal terms the special properties of knowledge as an input in production. The work on skills and layers in hierarchies gained traction once knowledge entered the picture.

At the meetings of the American Economic Association this weekend in Boston, a pair of sessions were devoted to going over that old ground, one on the “new growth economics” of the Eighties, another on the “optimal growth” literature of the Sixties. Those hoping for clear outcomes were disappointed.

Chicago’s Lucas; Paul Romer, of New York University; and Philippe Aghion, of Harvard University, talked at cross purposes, sometimes bitterly, while Aghion’s research partner, Peter Howitt, of Brown University, looked on.But Gene Grossman, of Princeton University, who with Elhanan Helpman, of Harvard University, was another contestant in what turned out to be a memorable race, put succinctly in his prepared remarks what he thought had happened:

Up until the mid-1980, studies of growth focused primarily on the accumulation of physical capital. But capital accumulation at a rate faster than the rate of population growth is likely to meet diminishing returns that can drive the marginal product of capital below a threshold in which the incentives for ongoing investment vanish. This observation led Romer (1990), Lucas, (1988), Aghion and Howitt (1992) Grossman and Helpman (1991) and others to focus instead on the accumulation of knowledge, be it embodied in textbooks and firms as “technology” or in people as “human capital.” Knowledge is different from physical capital inasmuch as it is often non-rivalrous; its use by one person or firm in some application does not preclude its simultaneous or subsequent use by others.

My guess is that “Knowledge-based Hierarchies: Using Organizations to Understand the Economy” will mark a watershed in this debate, the point after which arguments about the significance of knowledge will be downhill. “If one worker on his own doesn’t know how to program a robot, a team of ten similar worker will also fail,” write Garicano and Rossi-Hansberg. The only question is whether to make or buy the necessary know-how.

What’s new here is the implication that as inequality at top of the wage distribution grows, inequality at the bottom will diminish less, as the middle class is hollowed out.

[E]xperts, the superstars of the knowledge economy, earn a lot more while less knowledgeable workers become more equal since their knowledge becomes less useful. Moreover, communications technology allows superstars to leverage their expertise by hiring many workers who know little, thereby casting a shadow on the best workers who used to be the ones exclusively working with them. We call this the shadow of superstars.

For a poignant example of the shadow, see last week’s cover story in The Economist, Workers on Tap. The lead editorial rejoices that a young computer programmer in San Francisco can live like a princess, with chauffeurs, maids, chefs, personal shoppers. How? In There’s an App for That, the magazine explains that entrepreneurs are hiring “service pros” to perform nearly every conceivable service – Uber, Handy, SpoonRockert, Instacart are among the startups. These free-lancers earn something like $18 an hour. The most industrious among them, something like 20 percent of the workforce, earn as much as $30,000 a year. The entrepreneurs get rich. The taxi drivers, restaurateurs, grocers and secretaries who used to enjoy middle class livings are pressed.

Work on the organization-based view of economics is just beginning: Beyond lie all the interesting questions of industrial organization, economic development, trade and public finance. Much of the agenda is set out in the volume whose appearance marked the formal beginnings of the field, The Handbook of Organizational Economics (Princeton, 2013), edited by Robert Gibbons, of the Sloan School of Management of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and John Roberts, of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. Included is a lucid survey of the hierarchies literature by Garicano and Timothy Van Zandt, of INSEAD.

The next great expositor of economics, whoever she or he turns out to be, will give a very different account of the pencil.

. xxx

Andrew W. Marshall retired last week after 41 years as director of the Defense Department’s Office of Net Assessment, the Pentagon’s internal think-tank. A graduate of the University of Chicago, a veteran of the Cowles Commission and RAND Corp., Marshall was originally appointed by President Nixon, at the behest of Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, and reappointed by every president since. He served fourteen secretaries with little external commotion.

A biography to be published next week, The Last Warrior: Andrew Marshall and the Shaping of Modern American Defense Strategy (2015, Basic Books), by two former aides, Andrew Krepinevich and Barry Watts, is already generating commotion. Expect to hear more about Marshall in the coming year.

David Warsh, a longtime financial columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of www.economicprincipals.com.

David Warsh: They want a 'Fourth Revolution' in the West

BOSTON

When he was 18, before entering college, John Micklethwait toured the U.S. for a year with a friend, traveling on Greyhound buses. When they arrived in San Francisco, they spent a memorable evening with expat British businessman Antony Fisher, founder of London’s Institute of Economic Affairs, and his downstairs neighbor, Milton Friedman.

They talked about the possibilities now that Margaret Thatcher had become prime minister and Ronald Reagan president of the United States. The conversation made a deep impression on Mickelthwait. Then it was back to Magdalen College, Oxford, and an eventual career in journalism.

Today his companion is a major general, but Micklethwait commands many more battalions as editor-in-chief, since 2006, of The Economist. His new book is The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State, written with longtime collaborator Adrian Wooldridge, management editor of the magazine. They argue that the West should complete the revolution of the ’80s that Friedman started.

It won’t be easy, the authors acknowledge. Both the welfare state and democracy itself must be reined in, the former by redefining and reducing expectations of it; the latter by consensually imposing a series of self-denying limits: global budget caps, monetary targets, earmarked taxes, co-payments, borrowing ceilings, sunset provisions and the like.

The successful construction and adoption of such a fiscal constitution would amount to a “Fourth Revolution” in the nature of government in the West, they say. Previous revolutions they associate with three philosophers who at intervals wrote influentially on the role of the state. This catechism, a familiar device from their magazine, is designed to buttress the case for what they hope will happen next.

Thus, Thomas Hobbes described the fundamental purpose of the nation-state as the creation of law and order, thus the overwhelming force necessary to maintain the nation-state known ever since, at least to Hobbesians, as “Leviathan.” John Stuart Mill, who lived in a more prosperous time, imagined the state as a kind of “night watchman,” dedicated to free trade, social rights (of women in particular), and education. And Fabian Society socialist Beatrice Webb conjured a ”welfatre state” in the 20th century in which government influence extended into every sphere of production and consumption.

The authors are then off on a round of breathless reporting: to California, which they say illustrates everything that is wrong with modern democratic government, until, miraculously, under Gov. Jerry Brown, the state begins to straighten itself out; to Singapore, to see Lee Kuan Yew, founding father of a new model of national development, adopted in some ways by China, “that is in many ways leaner and more efficient than the decadent Western model”; to Sweden, where a wave of privatizations has reduced government spending in 20 years from 67 percent of GDP to 49 percent.

Along the way, we meet many of the usual suspects. Clayton Christensen, of the Harvard Business School, is “perhaps the world’s most respected writer on innovation,” who thinks that the public sector will be upset by what he calls “mutants” -- new organisms that may spin out from unexpected directions. (Their esteem is not universally shared.) Peter Theil, a prominent venture capitalist, laments that technology has so far failed to change the public sector.

Devi Shetty, an entrepreneur, “whom American surgeons may one day remember the same way that American engineers think of Kiichiro Toyoda,” has a production line of 40 cardiologists who perform 600 operations a week in Bangalore.

There is a peroration in the book:

"The Fourth Revolution is about many things. It is about harnessing the power of technology to provide better services. It is about finding clever ideas from every corner of the world. It is about getting rid of outdated labor practices. But at its heart it is about reviving the power of two great liberal ideas. It is about reviving the spirit of liberty by putting more emphasis on individual rights and less on social rights. And it is about reviving the spirit of democracy by lightening the burden of the state.''

One indication that history may not be tending in this direction is that the subject of climate change comes up nowhere in the book. This is odd because the weekly Economist does such a good job of reporting on the growing scientific consensus that global warming is becoming a serious problem.

Another contraindication is to be found in the authors’ proposal to “leapfrog over the muddle of Obamacare,” borrowing equally from “Old Europe and New Asia.” Why not combine a European-style single-payer health care system, featuring an independent medical board to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of medicines, devices and procedures, with means tests and a Singapore-style stream of earmarked taxes pay for it. That might strike Tea Party fundamentalists as socialism, they write, but it is precisely the kind of transparency-inducing global cap that they advocate in other connections, including Social Security.

It is not fair to place so much weight, as the authors do, on Milton Friedman’s shoulders. The Chicago economist, who was 94 when he died, in 2006, was a deeply consequential 20th Century figure whose role is not yet well understood. He may be fruitfully compared to John Maynard Keynes. Both men were authors of clarion wake-up calls. Keynes argued that government had a role in stabilization policy that it must not shirk; Friedman, that there are many economic ways to address a problem (including, presumably, the threat of global warming). Neither man was much concerned in his day with the finer points of economic analysis, but each commanded the attention and, ultimately, the agreement of his age. Other theorists, notably James Buchanan and Friedrich Hayek, have been more concerned with the idea of fiscal constitution.

At one point in their roundup, the authors quote Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire financial analytics entrepreneur who served three successful terms as mayor of New York City before returning to civilian life. Among other things,he oversees Bloomberg BusinessWeek, which he bought while he was mayor. Running a city is different from running a business, Bloomberg says.

''People are motivated by different things and you face a much more intrusive press. You cannot pay good staff a lot of money…. In business you experiment and you back the projects that win. The healthy bits get the money, and the unhealthy bits wither. In government the unhealthy bits get all the attention because they have the fiercest defenders.''

Doubtless so. But that doesn’t mean that governmental processes are not being improved, mainly along the lines advocated by Micklethwait and Wooldridge. Perhaps it is familiarity with the details that makes Bloomberg BusinessWeek so consistently interesting when it arrives along with The Economist each week. Hardly a week passes that I don’t compare the one to the other. In coverage of the Fourth Revolution, most weeks I think that the Americans are getting ahead.

xxx

A 14-page article, The Biden Agenda: Reckoning with Ukraine and Iraq, and keeping an eye on 2016, by Evan Osnos, in the current issue of The New Yorker, signals the vice-president’s willingness to contest the Democratic presidential nomination with former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. For both the politician and the journalist it is an impressive outing (Osnos, recently returned from China, is author of Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Fraith in the New China). The article would seem to promise a spirited campaign.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a longtime financial journalist, is proprietor of economic principals.com.

George Borts, 1927-2014

George H. Borts, 86, a distinguished economist, writer and editor, died May 2 in Providence.

Professor Borts was born in New York City on Aug. 29, 1927, and educated at Columbia University, where he earned an undergraduate degree at 19 and worked on the student newspaper, The Spectator. He received both his master’s degree (1949) and Ph.D. (1953) from the University of Chicago, where he studied under Milton Friedman, the famed libertarian economist – an experience that profoundly influenced his thinking about economics and other aspects of society for the rest of his life.

Professor Borts spent 63 years at Brown University, where he joined the Department of Economics in 1950 at 23. During his long and distinguished career, he served as chairman of the Department of Economics at Brown and led its rise to prominence as one of the leading departments of economic teaching and research. He was also the managing editor of one of the economics profession’s pre-eminent journals, the American Economic Review, for more than 10 years.

His career gave him the opportunity for travel, research and other learning as a visiting professor/research fellow at Hokkaido University, the London School of Economics and the National Bureau of Economic Research. He retired last year as the George S. and Nancy B. Parker Professor Emeritus of Economics.

Professor Borts was an expert in international finance, industrial organization, regulation and transportation. His legacy as an economist includes not only his books and dozens of scholarly papers, but the many lives he touched as a colleague, teacher, friend and adviser. Over more than six decades at Brown, George Borts had instructed and mentored thousands of undergraduate and graduate students. He supervised dozens of senior theses and doctoral dissertations and until last year, he was teaching undergraduate courses on international finance and on the welfare state in America, as well as leading several independent studies on a variety of topics.

His intellectual curiosity and professional interests allowed him to analyze complicated issues without pre-judgment. He led discussions about political, economic and social issues in ways that were clear and engaging for undergraduate seminars and senior colleagues alike. Generations of Brown students, economics majors and non-majors alike, discovered the intellectual creativity of economics through his classes.

His interest in promoting excellence in education was also demonstrated by his leadership of Brown’s Phi Beta Kappa chapter for many years.

He gave frequent testimony before U.S. and Canadian regulatory agencies and commissions and served on many boards, including those of the Rhode Island School of Design, Dartmouth’s Amos Tuck School of Business, Rhode Island Blue Shield, Junior Achievement of Rhode Island and Temple Beth-El in Providence. And he advised political candidates of both parties on economic and tax policy and provided commentaries for The Providence Journal. In 1990-91 he was the editor of the Brown World Business Advisory.

The managing editor of that publication, who became The Providence Journal’s editorial-page editor, Robert Whitcomb, called Professor Borts a “joy to work with’’ over the two decades of their occasional projects together. “He combined intellectual rigor with great humor and congeniality, including when we didn’t agree on a specific issue. I particularly enjoyed his often amusing application of the law of unintended consequences to many societal situations at our numerous pleasant meals together.’’

Although he was a tireless advocate of the free market, he viewed political issues through an economic lens that was fair and open-minded. He valued greatly his relationships with both Keynesian and Monetarist economists. His closest personal relationships were with such prominent advocates of alternative points of view as Hyman Minsky, Phillip Taft, and Jerome Stein. Further evidence of this non-ideological approach was his pronounced belief in the need for immigration reform.

He is survived by Dolly, his wife of 65 years, three sons, three grandchildren and many friends and admirers around America and beyond.