Todd McLeish: Finding rare species in Marine Monument off N.E.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A team of scientists from the New England Aquarium, in Boston, has been conducting periodic aerial surveys of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, some 130 miles off Nantucket, and has documented an impressive list of marine mammals and fish that illustrates why conservation organizations have been advocating for its protection for years.

A late-October survey, for instance, documented three species of rare beaked whales, three kinds of baleen whales, four species of dolphins, several ocean sunfish — the largest bony fish in the world — and two very unusual Chilean devil rays

“We’re out there documenting what’s out there to show that the area is important and should continue to be protected,” said Ester Quintana, the chief scientist of the aerial survey team. “Every survey is different, and you never know what you’re going to see, so it’s always exciting.”

The beaked whales were particularly notable, since they are rare and difficult to observe. Beaked whales are deep-diving species that can remain under water for more than an hour and only surface briefly to breathe.

“If you’re not at the location where they come to the surface, then you’re not going to see them,” Quintana said. “There are probably more of them out there that we were just not seeing.”

The survey team observed two Cuvier’s beaked whales, three Sowersby’s beaked whales, and four True’s beaked whales, the latter of which hadn’t previously been documented in the 4,900-square-mile monument during an aerial survey, though a ship-based group of researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration had seen several there last year.=

Also observed were large numbers of Risso’s dolphins, plus groups of bottlenose dolphins, common dolphins and striped dolphins, along with nine fin whales, two sperm whales, and one humpback.

“We didn’t see many individual whales, but that’s just the difference between an October survey and the surveys we’ve done in the summer,” Quintana said.

Of special note were the two Chilean devil rays observed, the first time Quintana had ever seen the species.

“Last year we saw a big manta ray, which was a surprising sighting because we were unaware that they could be sighted this far north,” she said. “So when we saw the Chilean devil ray at the site, it was another unexpected ray. They’re not that uncommon, but in the seven surveys we’ve conducted, it was the first we saw at the monument.”

About the size of Connecticut, the only Atlantic Ocean marine monument includes two distinct areas, one that covers three canyons and one that covers four seamounts. (NOAA).

Chilean devil rays can swim about a mile deep, and since they don't have to come to the surface to breathe, it’s unusual to see them.

The survey team flies transect lines back and forth over the three underwater canyons in the monument — Oceanographer Canyon, Gilbert Canyon and Lydonia Canyon — with most of the wildlife observed at Gilbert and Lydonia canyons. As soon as team members observe wildlife to document, they depart from their transect and circle the animal to identify and photograph it. The plane is equipped with a belly camera that takes photographs every 5 seconds during the survey in case the two observers miss anything.

Quintana said the team was unable to survey the waters around the monument’s four seamounts (underwater mountains), because those sites are farther away and their small plane can’t carry enough fuel to reach them.

The wide variety of marine life observed during the survey are attracted to the monument because of its diversity of habitats.

At a lecture last February describing the monument, Peter Auster, senior research scientist at Mystic Aquarium, in Mystic, Conn., said: “Those canyons and seamounts create varied ecotones in the deep ocean with wide depth ranges, a range of sediment types, steep gradients, complex topography, and currents that produce upwelling, which creates unique feeding opportunities for animals feeding in the water column.”

The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument was designated by President Obama in September 2016. It’s the only marine national monument in the Atlantic Ocean. Early in President Trump’s administration, he threatened to revoke the site’s designation, despite uncertainties as to whether he could legally do so. Those threats triggered efforts by conservation groups to document the value of the site to wildlife.

The next aerial survey by the New England Aquarium team will take place as soon as the weather cooperates. Conditions must be calm to allow for a safe flight and smooth seas so conditions are optimal for observing marine life.

“We’ve never done a survey in the winter because it’s hard to plan one because of the weather,” Quintana said. “No one has ever done a survey there in the winter, so we don’t know what to expect once we get there.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

A beaked whale

Fewer cold waves

Old Man Winter may be gradually losing his breath.

— Drawing by Etamme

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A Jan. 31 article in Bloomberg News, “Dangerous Cold Snaps Feel Even Worse Because They’re Now So Rare,’’ puts last week’s arctic attack in perspective. The authors write: “Temperature data since 1970 suggest that sudden freezes used to be much more normal, and the U.S. hasn’t had a good, old-fashioned cold streak in more than two decades.’’ Well, that assertion is debatable, but they usefully cite the work of Ken Kunkel, a researcher at North Carolina State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Atmosphere who for two decades has maintained a “cold wave index’’ record. Bloomberg explains that the index tracks “how often multi-day wintry blasts descend on the U.S.’’ Mr. Kunkel’s chart clearly shows a decline in the frequency of cold waves.

Rapid warming of the Arctic, linked to fossil-fuel burning, has screwed up the jet stream, which in turn sometimes lets big pockets of extremely cold air from Siberia and Canada move into the Mideast and Northeast, even as western North America gets much warmer than “normal’’. Ah, the “polar vortex’’. I love the hysteria that phrase creates!

Then the jet stream waviness changes and Mideast and Northeast turn much milder than normal, which has happened this week. To read the Bloomberg piece and chart, please hit this link.

Environmental factors in decline of shellfish along East Coast

Bay scallop.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.og)

Researchers studying the sharp decline between 1980 and 2010 in documented landings of the four most commercially important bivalve mollusks — eastern oysters, northern quahogs, soft-shell clams and northern bay scallops — have identified the causes.

Warming ocean temperatures associated with a positive shift in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which led to habitat degradation including increased predation, are the key reasons for the decline of these four species in estuaries and bays from Maine to North Carolina, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The NAO is an irregular fluctuation of atmospheric pressure over the North Atlantic Ocean that impacts both weather and climate, especially in the winter and early spring in eastern North America and Europe. Shifts in the NAO affect the timing of species’ reproduction and growth, the availability of phytoplankton for food, and predator-prey relationships, all of which contribute to species abundance. The findings appear in Marine Fisheries Review.

“In the past, declines in bivalve mollusks have often been attributed to overfishing,” said Clyde Mackenzie, a shellfish researcher at NOAA Fisheries’ James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory, in Sandy Hook, N.J., and lead author of the study. “We tried to understand the true causes of the decline, and after a lot of research and interviews with shellfishermen, shellfish constables, and others, we suggest that habitat degradation from a variety of environmental factors, not overfishing, is the primary reason.”

Mackenzie and co-author Mitchell Tarnowski, a shellfish biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, provide details on the declines of these four species. They also note the related decline by an average of 89 percent in the numbers of shellfishermen who harvested the mollusks. The landings declines between 1980 and 2010 are in contrast to much higher and consistent shellfish landings between 1950 and 1980.

Exceptions to these declines have been a sharp increase in the landings of northern quahogs in Connecticut and American lobsters in Maine. Landings of American lobsters from southern Massachusetts to New Jersey, however, have fallen sharply as water temperatures in those areas have risen.

“A major change to the bivalve habitats occurred when the North Atlantic Oscillation index switched from negative during about 1950 to 1980, when winter temperatures were relatively cool, to positive, resulting in warmer winter temperatures from about 1982 until about 2003,” Mackenzie said. “We suggest that this climate shift affected the bivalves and their associated biota enough to cause the declines.”

This graph shows the rise and fall of soft-shell clam landings from 1950 to 2005. (Clyde Mackenzie)

Research from extensive habitat studies in Narragansett Bay and in the Netherlands, where environments including salinities are very similar to the northeastern United States, show that body weights of the bivalves, their nutrition, timing of spawning, and mortalities from predation were sufficient to force the decline. Other factors likely impacting the decline were poor water quality, loss of eelgrass in some locations for larvae to attach to and grow, and not enough food available for adult shellfish and their larvae.

“In the Northeast U.S., annual recruitments of juvenile bivalves can vary by two or three orders of magnitude,” said Mackenzie, who has been studying bay scallop beds on Martha’s Vineyard with local shellfish constables and fishermen monthly during warm seasons for several years.

In late spring to early summer of this year, a cool spell combined with extremely cloudy weather may have interrupted scallop spawning, leading to what looks like poor recruitment this year. Last year, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard had very good harvests due to large recruitments in 2016.

“The rates of survival and growth to eventual market size for shellfish vary as much as the weather and climate,” Mackenzie said.

Weak consumer demand for shellfish, particularly oysters, in the 1980s and early 1990s has shifted to fairly strong demand as strict guidelines were put in place by the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference in the late 1990s regarding safe shellfish handling, processing, and testing for bacteria and other pathogens.

Enforcement by state health officials has been strict. The development of oyster aquaculture and increased marketing of branded oysters in raw bars and restaurants has led to an increase in oyster consumption in recent years.

Since the late 2000s, the NAO index has generally been fairly neutral, neither very positive nor negative. As a consequence, landings of all four shellfish species have been increasing in some locations. Poor weather for bay scallop recruitment in both 2017 and 2018, however, will likely mean a downturn in landings during the next two seasons.

Frank Carini: Rhode Island tries to deal with a rising sea

Here at the Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge, in Middletown, R.I., the Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service are working to restore and strengthen salt-marsh habitat as the rising sea level poses an intensifying challenge.

Via ecoRI News (ecofri.org)

NARRAGANSETT, R.I. — Rhode Island is losing and has lost thousands of acres of salt marsh, much of it to development. These unique ecosystems are a priceless resource with irreplaceable benefits, including their ability to protect the human-built world from sea-level rise.

“We’re going to hit a point when marshes can’t keep up with sea-level rise,” University of Rhode Island researcher Simon Engelhart said. “We need to let them migrate inland, or we will lose them. We need to allow marshes to do what marshes do.”

He said humans should already be retreating from the coastline. He also noted that the clearing of trees and the destabilization of soil impacts the ability of salt marshes to migrate inland.

Engelhart, an assistant professor in URI’s Department of GeoSciences, is investigating how the state’s coastline has responded to past sea level-rise changes and studying the influence of land subsidence from the last ice age to better understand future implications as sea level-rise projections continue to climb.

So far, his research has found that sea-level rise is happening faster than at any point in Rhode Island’s past 3,000 years, in part because the Ocean State is sinking. Low-lying areas such as Island Park, in Portsmouth, and Oakland Beach, in Warwick, are among the most vulnerable areas.

Engelhart noted that sea-level rise is a complicated issue with many variables, such as gravity, density changes of water, water temperatures, the strength of the Gulf Stream and other ocean currents, the draining of aquifers, groundwater withdrawals, and the rate of ice-sheet melting in Greenland, the West Antarctic, the East Antarctic and the Southern Patagonian Ice Field.

“It doesn’t go up uniformly everywhere. The ground moves, shakes and is active,” Engelhart said during a Feb. 14 talk at the Coastal Institute Auditorium on URI’s Bay Campus as part of Rhode Island Sea Grant’s annual Coastal State Discussion Series. “Sea-level rise is about what the ocean is doing and what the land is doing.”

Although Rhode Island is losing only 1 millimeter of ground annually, according to Engelhart, it plays a meaningful role in present-day flooding along a coastal state that is mostly at sea level or 10-30 feet above.

He said land subsidence — the gradual settling or sudden sinking of the Earth’s surface owing to subsurface movement of earth materials — “is going to be important in the short-term even though it’s small because it’s still a component of what we’re seeing,” referring to nuisance flooding where high tides can now cause road closures and overwhelm storm drains. These events are expected to increase with continuing sea-level rise, he added.

“This may seem minimal compared to projected sea levels, but is still a significant contributor to sea-level rise at present,” Engelhart said.

Since 1930 the Newport tide gauge has measured about 2.7 millimeters annually of relative sea-level rise. The Providence tide gauge has measured 2.2 millimeters. Those measurements, however, don’t tell the full story.

“Eighty to ninety years of data is not enough to put anything into context,” Engelhart said. “Those are just linear rates ... they’re not accounting for the acceleration of the current rate. There’s clear acceleration in the records of the past 25 years. We need to address greenhouse-gas emissions.”

Last year the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration increased its sea-level rise projectionsto up to 8 feet by 2100. The Northeast is projected to experience an additional 1-3 feet on top of NOAA modeling.

Salt marshes are highly productive ecosystems that filter out pollution, provide habitat for wildlife and protect homes from flooding. They’re also sensitive to development.

For the long-term context of Rhode Island sea-level rise, Engelhart and his research team turned to Narragansett Bay salt marshes. He explained that salt marshes grow at different elevations to the ocean and that life in them tells a specific story. To read these marsh stories, Engelhart’s team has taken core samples from four salt marshes — Fox Hill, Touisset, Nag Creek and Osamequin — and closely examined their finds with radiocarbon dating.

The team has plans to expand the number of salt marshes where core samples are taken.

Salt marshes are shoreline wetlands that are flooded and drained by salt water brought in by the tides. These intertidal ecosystems — foraging habitat for fish, shellfish, birds and mammals, and home to nursery areas and spawning grounds — are essential for healthy coastlines, communities and fisheries. They are an integral part of Rhode Island’s economy and culture.

They also have and continue to take a pounding. For instance, more than 50 percent of Narragansett Bay’s salt marshes have been destroyed during the past three centuries. Much of the remaining marshes have been diminished by coastal development and failed mosquito ditching. Mosquito ditches are narrow channels that were dug to drain the upper reaches of salt marshes. It was believed that such efforts would control mosquito breeding, but all that work did was drain salt marshes and kill off mummichogs, a mosquito-eating fish that are important prey for herons, egrets and larger predatory fish.

Healthy salt marshes help communities, buildings, infrastructure and the environment better withstand the impacts of sea-level rise and coastal storm surge. Salt marshes protect shorelines from erosion by buffering wave action and trapping sediment. These vital ecosystems reduce flooding by absorbing rainwater, and protect water quality by filtering runoff and metabolizing excess nutrients, such as nitrogen.

Salt marshes, however, are highly sensitive to development. Polluted stormwater runoff from inland development can damage salt-marsh health. Engelhart also noted that the marshes of Narragansett Bay face another problem: a lack of sediment supply.

James Boyd of the state’s Coastal Resources Management Council partook in an informal conversation, which included about a dozen questions from the audience, after Engelhart’s recent presentation.

Boyd noted that if sea level in Rhode Island rose a foot, 13 percent of the state’s remaining salt marshes would be lost; 3 feet, 62 percent; 5 feet, 83 percent.

“Our salt marshes are in trouble,” said the coastal policy analyst. “The ability of salt marshes to migrate inland is the most important element. We need to preserve that upland. That’s what will save our salt marshes: room to move.”

The impact of losing healthy salt marsh can be seen across southern New England. The coastal portion of the Sapowet Marsh Wildlife Management Area, in Tiverton, has experienced more than 90 feet of shoreline erosion in the past 75 years, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service are working to restore and strengthen salt-marsh habitat at the Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge, in Middletown, to better withstand the impacts of sea-level rise, coastal storm surge and coastal erosion.

Salt marshes of the picturesque Narrow River are threatened by a combination of rising water and human activity. In recent years, motorboat wakes and extreme weather events such as Hurricane Sandy have destroyed 15 percent of the watershed’s marshland, according to state officials.

Salt-marsh islands in the West Branch of the Westport River have declined by nearly half during the past 80 years, according to a 2017 report.

By studying aerial imagery of six salt-marsh islands in the river’s West Branch, scientists found that the total area of salt marshes has consistently declined during the past eight decades, with losses dramatically increasing in the past 15 years. Altogether, the six islands lost a total of 12 acres of salt marsh since 1938. If marsh losses continue at the accelerated rate observed during the past 15 years, the Westport River’s marsh islands could disappear within 15 to 58 years, according to the researchers.

“Plan for the worst-case scenario is the best way to handle sea-level rise,” Engelhart said. “Take the longer-term view. There’s benefits regardless if we cut greenhouse-gas emissions.”

Engelhart’s research aims to provide a better understanding of future coastal hazards, to help coastal planners make more informed decisions.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Using ribbed mussels to clean water

Ribbed mussel.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

MILFORD, Conn.

Ribbed mussels can remove nitrogen and other excess nutrients from an urban estuary and could help improve water quality in other urban and coastal locations, according to a study in New York City’s Bronx River. The findings, published in Environmental Science & Technology, are part of long-term efforts to improve water quality in the Bronx River estuary.

Researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Fisheries Milford Laboratory began the two-year pilot project in June 2011. They used a 20-by-20-foot raft with mussel growing lines hanging below as their field location in an industrial area near Hunt’s Point, in the South Bronx, not far from a sewage-treatment plant. The waters were closed to shellfish harvesting because of bacterial contamination. Scientists monitored the condition of the ribbed mussels and water quality over time to see how each responded.

“Ribbed mussels live in estuarine habitats and can filter bacteria, microalgae, nutrients and contaminants from the water,” said Julie Rose, a research ecologist at the Milford Laboratory, part of the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, and co-author of the study. “They are native to the East Coast so there are no concerns about invasive species disturbing the ecosystem, and they are efficient at filtering a variety of particles from the water. Ribbed mussels are not sold commercially, so whatever they eat will not be eaten by humans.”

Farming and harvesting shellfish to remove nitrogen and other excess nutrients from rivers, estuaries and coastal waters is known as nutrient bioextraction, or bioharvesting. Mussels and other shellfish are filter feeders, and as the organisms grow, they take up or assimilate nutrients in algae and other microorganisms filtered from the surrounding waters.

Nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients occur naturally in the environment and are needed by plants and animals to grow, but too much of any of them is harmful. Excess amounts from human activities often end up in rivers, streams and coastal environments, causing algal blooms, loss of seagrass and low oxygen levels, which can kill large numbers of fish.

Researchers found that the Bronx River mussels were generally healthy, and their tissues had high amounts of a local nitrogen isotope, indicating that they removed nitrogen from local waters. They also had lower amounts of trace metals and organic contaminants than blue mussels collected from the seafloor nearby. An estimated 138 pounds of nitrogen was removed from the river when the ribbed mussels were harvested.

The researchers estimate that a fully populated 20-by-20-foot mussel raft similar to the one used in the study would clean an average of 3 million gallons of water and remove about 350 pounds of particulate matter, such as dust and soot, daily. When harvested, the animals could be used for fertilizer or as feed for some animals, recycling nutrients back into the land.

The mussel raft was placed at the confluence of the East River tidal strait and the Bronx River in a high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll system, making the site unsuitable for large-scale mussel growth. Future projects using ribbed mussels for nutrient remediation will need spat or larvae from another location or from hatchery production.

“Management programs to reduce the effects of excess nutrients in the water have largely focused on land-based sources, such as human and livestock waste, agriculture, and stormwater runoff,” said Gary Wikfors, Milford Laboratory director and co-author of the study. “They really haven’t looked much at recovering the excess in the water itself. Nutrient bioextraction using shellfish is becoming more common, and this study demonstrated that it could be an additional tool for nitrogen management in the coastal environment.”

The Bronx study is the first to examine the use of ribbed mussels for nutrient bioextraction in a highly urbanized estuarine environment. A previous study comparing the Bronx River to the more productive Milford Harbor estuary indicated that ribbed mussels were able to adapt in just a few days to low food availability and feed with the same efficiency in the Bronx River site as populations at the Milford River site. That study also supports the use of ribbed mussels as a management tool for nutrient bioextraction in a range of coastal environments.

UNH, NOAA expanding ocean-mapping center

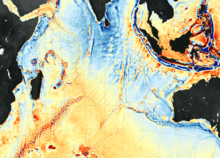

Seafloor map of southern Indian Ocean.

This is from the New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

"NEC member the University of New Hampshire (UNH) — in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – is expanding its Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping and Joint Hydrographic Center by adding nine additional labs, offices, and an amphitheater. The joint UNH-NOAA initiative was established in 2000 with the goal of mapping the worldwide ocean floor.

"Students and scientists at the center on UNH’s Durham campus monitor live streams from ships that are collecting data of ocean floor, track fish and whale patterns, and create 3D prototypes. Currently, only 11% of the ocean’s 140 million square mile floor is mapped and internationally, scientists aim to complete a map of the ocean floor in the next thirteen years to ensure ships can safely navigate the ocean by being aware of any potential hazards below them. The center is home to 25 students and scholars from around the world who work with both the private sector and government agencies to achieve that goal.

'''I’ve always wanted to explore the ocean for as long as I can remember. We have better maps of the moon than we do of the ocean,' said UNH student Victoria Dickey during U.S. Rep. Carol Shea-Porter’s recent visit to the center.''

To read more, hit this link.

Tim Faulkner: Senate rejects Trump cuts to coastal environmental projects

The Sakonnet River, a saltwater strait that forms part of Narragansett Bay.

Via eco RI News (ecori.org)

On the same night that the U.S. Senate rejected the latest effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, it also come out forcefully against President Trump’s effort to eliminate funding for key coastal programs.

In its funding bill for the departments of Commerce, Justice and Science, the Senate approved funding for the Coastal Resources Management Council, Sea Grant and the National Estuarine Research Reserves.

Instead of level funding, the Senate increased by $2 million to $76.5 million for the Sea Grant program, a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“The Committee flatly rejects the [Trump] administration’s proposed elimination of NOAA's Sea Grant program,” the Senate Appropriations Committee wrote in a statement regarding the 2018 funding bill.

The Sea Grant program at the University of Rhode Island is one of 33 nationwide affiliated with universities located near salt water and the Great Lakes. New England has eight Sea Grant offices that focus on coastal hazards, sustainable coastal development, and seafood safety.

Rhode Island Sea Grant receives $2 million from the federal government annually to run its research center at URI’s Bay Campus, in Narragansett. Another $1 million is provided by the state and other sources. Its research includes studies of algal blooms, oyster farming, and lobster diseases.

Had Trump’s budget passed, nine positions would have been lost between the URI research center and a laboratory at Roger William University, in Bristol.

“We are very pleased that the House and Senate have rejected the president’s request to terminate the program,” said Dennis Nixon, director of Rhode Island Sea Grant.

Nixon said Sea Grant has no critics in Congress and that it seen as a valuable institution for advancing timely research.

Trump has been accused of using a broad brush to eliminate any program with the word “grant” in it, to increase defense spending and pay for a border wall with Mexico.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and other Washington insiders maintain that the president’s budget holds little influence on spending and that Congress ultimately decides how money is appropriated. Soon after Trump released his proposed budget in March, Whitehouse downplayed major funding cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency and other environmental programs such as Sea Grant.

“Do not be dissuaded or dismayed by the cuts to EPA, the elimination of Sea Grant and other such efforts,” Whitehouse said on March 11. “It is an act of political theater; it is not an act of budgeting.”

Some $85 million was also restored for coastal management grants. The funds pay for about 60 percent of the budget for the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC), a state agency based in Wakefield. CRMC is responsible for permitting coastal development such as docks and seawalls. The 46-year-old agency also creates planning guidelines for offshore wind development and climate-change adaptation. Its Ocean Special Area Management Plan is considered one of the most advanced coastal planning documents in the country.

The Narragansett Bay Estuarine Reserve, based on Prudence Island, had its 70 percent of federal funding restored. The research reserve has eight employees and an $850,000 annual budget. It's one of 28 research reserves nationwide. The Rhode Island facility conducts research and monitoring of shoreline habitat. Recent projects have focused on eelgrass and the Asian shore crab.

The U.S. House of Representatives already passed similar funding for these coastal programs. The two budgets are expected to be modified slightly to match before they are fully approved for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1.

“It’s good news that both the House and Senate are funding the coastal programs,” said Grover Fugate, CRMC's executive director.

Tim Faulkner writes frequently for ecoRI News.

Tim Faulkner: Coming soon -- live war exercises for the East Coast

--Navy map

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The Navy intends to fire missiles, rockets, lasers, grenades and torpedoes, detonate mines and explosive buoys, and use all types of sonar in a series of live war exercises in inland and offshore waters along the East Coast.

In New England, the areas where the weapons and sonar may be deployed encompass the entire coastline, as well as Navy pier-side locations, port transit channels, civilian ports, bays, harbors, airports and inland waterways.

“The Navy must train the way we fight,” according to a promotional video for what is called "Atlantic Fleet Training and Testing Phase III."

An environmental impact study of the war games was released June 30. Public comment is open until Aug. 29. A public hearing is scheduled for July 19 from 4-8 p.m. at Hotel Providence. Comments can be submitted onlineand in writing, or through a voice recorder at the hearing.

The dates and exact locations of the live weapon and sonar exercises haven't yet been released. In all, 2.6 million square miles of land and sea along the Atlantic Coast and Gulf of Mexico will be part of the aerial and underwater weapons firing.

The Navy has designated southern New England as the Boston Operating Area, Narragansett Operating Area and Newport Testing Range.

The Navy describes the weapons exercise as a “major action.” The live ammunition training includes the use of long-range gunnery, mine training, air warfare, amphibious warfare, and anti-submarine warfare. The Navy says weapons use near civilian locations is consistent with training that has been done for decades.

The Navy, in conjunction with the National Marine Fisheries Service, will announce one of three options for the battle exercises by fall 2018. One of the options is a “no-action alternative.”

The Office of the Secretary of the Navy has full authority to approve or deny the live war games. President Trump, however, has had difficulties finding a new Navy secretary. Venture capitalist Richard V. Spencer is expected to face a Senate confirmation hearing this month. Previous nominee Philip Bilden withdrew from consideration in February over financial-disclosure requirements.

The Navy says an environmental review for the excises was conducted between 2009 and 2011.

The live war games would deploy passive and active sonar systems. The Navy said it will use mid-frequency active acoustic sonar systems to track mines and torpedoes. Air guns, pile driving, transducers, explosive boxes and towed explosive devises may be used offshore and inland.

Risks to sea life include entanglements, vessel strikes, ingesting of harmful materials, hearing loss, physiological stress, and changes in behavior.

The Navy says it is using acoustic modeling done by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to minimize impacts to marine mammals such as whales and porpoises. NOAA, however, isn't involved with efforts to mitigate environmental impacts during the war games. Spotters on naval vessels will search for mammals during the exercises. The Navy said it will partner with the scientific community to lessen impacts on birds, whales, turtles, fish and reefs.

While some sea life is expected to be harmed by the explosives and sonar, the Navy says it doesn't expect to threaten an entire population of a species.

Tim Faulkner writes frequently for ecoRI News.

Tim Faulkner: Projected sea-level rise looks scarier

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A stitch in time saves nine. A cat has nine lives. Baseball legend Ted Williams wore No. 9. Unfortunately for Rhode Island, nine is also the new number for the feet of projected sea-level rise.

Just a few years ago, the upper estimate for sea-level rise was 3 feet. More recently, it was 6.6 feet. But a recent assessment by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects sea-level rise to increase in Rhode Island by 9 feet, 10 inches by 2100.

“To put in perspective we’ve had 10 inches (of sea-level rise) during the last 90 years. We’re about to have 10 feet in the next 80 years,” said Grover Fugate, executive director of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC).

Fugate made the remarks during a recent environmental business roundtable featuring the state’s top energy and environment officials: Fugate; Janet Coit, executive director of the Department of Environmental Management; and Carol Grant, commissioner of the Office of Energy Resources.

Coit and Grant highlighted the positive trends in Rhode Island's “green economy,” such as growth in renewable energy and the fishing industry. Fugate spoke last and, referring to himself as the “Debbie Downer” of the meeting, straightaway delivered the bad news facing the state from climate change.

“I’ve been director here for 31 years and the numbers we are seeing are staggering to me,” Fugate said of the NOAA report. “The changes we are going to see to our shoreline are profound, dramatic, and there is going to be a lot of economic adjustment going forward."

The major upward revision in sea level-rise projections, he said, will be transformative to life in Rhode Island, particularly along the coastal region of Washington County and much of Bristol County and Warwick.

To drive the point home, Fugate showed photographs of severe beach erosion along Matunuck Beach in South Kingstown. The shoreline there has been eroding at a clip of 4 feet annually since the 1990s. Recently, the rate climbed to 8 feet a year. That level was calculated before NOAA released the latest projected increase in sea-level rise.

Higher seas, Fugate said, create a multiplier effect that intensifies coastal erosion and flooding. Tides and storm surges reach further inland. Climate change also produces stronger wind and rain events. Thus, a storm classified as a 50-year event can cause the same damage as a 100-year event, according to Fugate.

The recent NOAA report says the principal cause for higher seas is the melting of land-based ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Since 2009, the region from Virginia north to the Canadian Maritime Provinces has experienced accelerated sea-level rise due to changing ocean currents in the Gulf Stream. NOAA expects that trend to continue.

According to the report, the impact of prolonged sea-level rise will be loss of life, damage to infrastructure and the built environment, permanent loss of land, ecological transformation of coastal wetlands and estuaries, and water-quality impairment.

Those impacts, Fugate said, are already here and being felt. He showed slides of storm drains flowing backwards and flooding parking lots during regular high tides, and buildings that are becoming islands. Coit noted that wetlands and marshes are essentially drowning in this higher water.

“The future is here now,” Fugate said. “It’s here and we are seeing profound changes.”

To combat climate change, coastal buildings are being elevated thanks to federal incentives. The CRMC also has permissive policies that allow for the rebuilding of sea walls damaged by these more forceful storms and accelerated erosion.

Several environmental engineers and municipal planners at the recent meeting raised questions about the need for policies and regulations to address threatened infrastructure, such as septic systems, utilities, and spoke about the risk of inland river flooding. Their queries suggested that the state is taking a piecemeal approach to a vast problem.

The environmental group Save The Bay has criticized an Army Corps of Engineers plan to provide funding to elevate homes along the Rhode Island coast from Westerly to Narragansett, R.I. Fugate said that plan has flaws, but endorses the concept as the best solution for protecting property owners.

Save The Bay, however, wants greater consideration given to migration away from the coast. Retreat from a receding shoreline, it argues, protects people, as well as the ecological health and resilience of the natural resource that defines the Ocean State.

“Are we going to elevate homes that can’t be reached because the roads are under water?” asked Topher Hamblett, Save The Bay’s policy director. “I think the state needs a long-term strategy about moving back from the coast.”

Hamblett portended that coastal retreat would greatly impact the real-estate market and present enormous challenges for policymakers and elected officials.

“But this is so big on so many levels that unless and until we start really seriously planning to move back out of harms way, we are going to inflict a lot of otherwise avoidable damage on ourselves,” Hamblett said.

Fugate and Coit said elevating buildings may not be the best option, but it's the only one currently with funding. If approved, it would provide about $60 million of federal relief money apportioned after Hurricane Sandy.

“Yes, the money would be better spent in another way,” Coit said. “Could we protect more land on the shore and in the flood plains? Could we help people move out all together through a buy-out program? Could we look at infrastructure that helps the whole public instead of the individual homeowner?”

Fugate said the problem is compounded by federal flood-insurance maps that created immense controversy in 2013, when the Federal Emergency Management Agency released inaccurate flood-zone maps. Those maps led to astronomically high insurance premiums for some and rampant confusion among others living on or near the water.

Fortunately, Fugate said, the CRMC and the University of Rhode Island have designed interactive maps forecasting the impacts of sea-level rise, coastal flooding and storm surge. The modeling behind those maps is helping remedy the flood-map problem. Nevertheless, Fugate encouraged anyone with property in a flood zone to buy flood insurance.

Coit said the state is in a good position to address sea-level rise and climate change by following the same model that led to the development of the Block Island Wind Farm. The Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) brought together federal, local and private stakeholders to craft a plan for mapping out public and private uses for offshore regions. CRMC is working on a similar Shoreline SAMP to address long-term coastal planning.

Coit said the state Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) is already addressing comprehensive climate-change planning for the state. The EC4 recently released an assessment of Rhode Island's greenhouse gas-emissions reduction plan. It’s now scrutinizing flooding at wastewater treatment facilities, among other threats from climate change.

“I think we are in a good place for Rhode Island to really look holistically at a resiliency and adaptation plan that takes into account all of the issues,” Coit said.

Most of the EC4’s funding comes from the Environmental Protection Agency. CRMC gets half of its budget from the Department of Commerce. But Coit, Grant and Fugate say President Trump’s hostility toward climate change won’t curtail state planning efforts, much less the realities of sea-level rise and global warming.

While the NOAA report doesn’t offer its own solutions, it concludes that sea-level rise is unrelenting.

“Even if society sharply reduces emissions in the coming decades, sea level will most likely continue to rise for centuries,” according to NOAA.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.

Pearl Macek: N.E. ocean fishermen worry about sector's sustainability

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

PROVIDENCE

Fishermen, scientists and interested citizens gathered in mid-April at Rhode Island College for a panel discussion about whether commercial ocean fishing is, or can be, sustainable.

The panel consisted of six speakers who discussed the current state of fish populations within U.S. waters, climate change and its impact on fish stocks, and the current rules and regulations imposed on commercial fishermen. The discussion was often heated, and it was obvious that the fishermen, both on the panel and in the audience, weren’t happy with current catch quotas and monitoring regulations.

Panelist John Bullard, the Northeast regional administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said commercial fishing is “definitely sustainable.” But fishermen David Goethel and Mark Phillips, also on the panel, believe the more important question to explore is whether fishing communities are sustainable. Both fishermen said catch quotas and the crippling expenses fishermen have to face both to run their boats and pay catch monitors are making fishing as a way of life all but impossible.

“The smell of fish is gone, replaced by burnt coffee,” Phillips said about the traditional fishing docks of New England.

NOAA regulates the fishing industry, and both Phillips and Goethel are involved in a lawsuit against the federal agency regarding the costs incurred by New England fishermen who now have to pay monitors about $700 a day to be on their boats.

Traditionally, the monitoring system was federally funded, but commercial fishermen now have to pay the monitors’ wages, a burden that many fishermen believe will push them toward bankruptcy. The lawsuit was filed last December in federal district court in Concord, N.H.

The audience clapped almost every time Phillips and Goethel spoke about the need for less regulation and more freedom to continue the tradition of small-scale commercial fishing. Phillips bemoaned the fact that U.S. fishermen are only allowed to fish one-third of Georges Bank, one of the most valuable fishing grounds off North America and easily accessible by New England fishermen.

He said fish stocks follow a natural cycle completely independent of fishing, and that every 15 to 20 years a fish population crashes and then rebounds. Phillips also said that when fishermen aren’t allowed to harvest a particular fish stock, the population often times dies off because of disease caused, at least in part, by overpopulation. He claimed there are more fish in the Atlantic Ocean than there were 20 to 30 years ago.

NOAA recently released its annual report to Congress on the status of U.S. fisheries and the numbers are fairly promising: the number of stocks listed as subject to overfishing or overfished remain near an all-time low, with only 9 percent of stocks subject to overfishing and 16 percent of stocks being overfished. Overfishing occurs when more fish are caught then the population can replace; overfished means the current population is 35 percent or below the estimated original population. A fish population can become overfished for reasons outside of fishing, such as disease, natural mortality and changes in environmental conditions.

The topic of climate change also came up frequently in the conversation.

“Climate change is a big problem we have to face,” said Jake Kritzer, director of the Fishery Solutions Center team at the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group. He noted that a reduction in salinity and nutrients in ocean waters has caused a decrease in the production of plankton.

“Every fishery management plan has to take climate change into consideration,” Bullard said. He also spoke about whole species of fish and marine crustaceans moving further north as New England’s coastal waters get warmer. In recent years, Maine lobstermen have experienced a glut of lobster, which drove prices down to the point that fishermen refused to harvest them until prices increased.

“Fisherman should be advocates,” said Graham Forrester, a professor in the Department of Natural Resources Science at the University of Rhode Island, as he tried to be a unifying voice on a panel that was bitterly divided between fishermen and scientists. “We are struggling in the scientific community to understand these problems.”

At the beginning of the discussion, each member of the audience was given an electronic remote control with which they could answer if they thought fishing was sustainable. At the beginning of the discussion, 69 percent of the audience said yes; by the end of the discussion, that number increased to 78 percent.

In the panelists’ closing remarks Bullard extended a metaphorical olive branch to the fishermen both on the panel and in the audience by saying that regulating the fishing industry needed to be improved, because fishermen have the “hardest job in the world” and “we are making their place of business a hostile environment.”

Pearl Macek is a contributing writer for ecoRI News.

Jim Bedell: Sea-level rise threatens public's access to Rhode Island's shore

via ecoRI News

(ecori.org)

The scary part is the consolidating evidence of global warming, the surprising acceleration of sea-level rise and the accepting of the profound effects these will have on Rhode Island. The hopeful part is the proactive call to arms by this little state, stepping out in front of the crowd to take meaningful action to deal with the changes coming our way.

Those steps come in the package of the Rhode Island Coastal Resource Management Council’s Shoreline Special Area Management Plan (Beach SAMP). If you don’t know what that is, well, start paying attention.

It’s time to look over the time horizon. Sea-level rise is accelerating way beyond previous assumptions. Before anthropogenic warming began accelerating in the mid-1900s, scientists spoke of natural post-glacial sea-level rise in terms of a few inches per century. The latest National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projections cite the range in sea-level rise above 1990 levels to be a maximum of 7 feet by 2100. The youngest of our current schoolchildren will live long enough to see Waterplace Park, Galilee, Misquamicut and much of Wickford and lower Newport under water, and whole waterfront neighborhoods abandoned.

Now several years in progress, the Beach SAMP process has been a national leader in preparing to deal with coming realities. Our state university, world renowned in oceanography and earth science, has been a blessing. It has been gathering data, holding public discussions, and putting together useful proposals to help shore towns and cities think, and more importantly act, to minimize the cost and disruption of the coming changes.

A good example of an early proactive measure is the “armoring” of the sewage-treatment facility in Narragansett, near Scarborough State Beach. The proposed earthen berm — an artificial ridge or embankment — and wall will be needed to protect critical infrastructure from damage in the future as the sea rises.

But there is something else that needs protection as the coastal future becomes the coastal now, and Save The Bay has taken a step to make sure that it’s included in the Beach SAMP. Save The Bay and CRMC are also protecting the people of Rhode Island in another important way: They’re protecting our precious and unique right to use the shore. Among other rights of the shore, we have the right to “pass along the shore.”

Save The Bay has entered an opinion regarding the Narragansett sewer project, saying that without including a way to walk, fish or collect seashells along the shore in front of the sewerage plant, the engineering for the project isn’t complete and it shouldn’t go forward. The nonprofit advocacy organization has proposed moving the protection structure 40 feet landward to allow passage in front of it. That would be a good thing.

I would add an alternative proposal if another is needed. Namely, if the barrier truly can’t be moved inland, put a walkway along the top of the structure to allow passage across the treatment property to the beach on the other side.

Most certainly creative, outside-the-box solutions will have to be part of the remedy for this never-before experience of dealing with such rapidly accelerating climate change.

Of course, the sewer plant project in Narragansett is just one pixel in a much larger picture. As another example, I have included a pair of pictures from the Beach SAMP data available on the CRMC Web site titled “Shoreline Change Maps.” One shows a satellite view of a house and a hotel on Misquamicut Beach along Atlantic Avenue in Westerly with the movement of the land/water boundary, identified by colored lines, during the past 77 years. You can see that both locations have constructed boulder walls across their property.

There are several important things to learn from these photos.

One lesson comes from the boxes at the end of the survey lines going out into the water. The black box shows the total movement landward of the land/water boundary since 1939. At line No. 169 it has moved 109 feet, which means that 109 feet of real estate has disappeared. The learning comes with realizing that although the sea has risen only a number of inches over this time, the land/water boundary location moves many feet landward because the land, in most places, is a gentle slope rising away from the water.

The white boxes show the same survey data in another way. They show the average number of feet per year the shore has moved inland. At the location of line No. 169 it has been retreating at an average rate of 1.5 feet annually.

The colored lines highlight the second lesson we can gleam from this CRMC image. The red line is 1939, the black is 1951, the purple is 1963, the green is 2012 and the blue is 2014. Notice that through 1951 the shoreline was far enough in front of the house and hotel that there was room for anyone to pass along the beach without any problem.

By 2012, the sea had risen up to the point that there was no longer anywhere to walk to pass along the beach. By 2014, a person would have to hazard rock climbing the wall to get by along the shore.

Bear in mind that people don’t come to Misquamicut for the restaurants and hotels and happen to use the beach. The restaurants and hotels only exist there because of the fabulous, unobstructed, world-class strand of sand on which they can recreate. Every year, the town of Westerly takes in millions of dollars because of the miles-long beach that people can enjoy and “pass along.” Protecting lateral access along the shore is as much a local economic business issue as it is an emotional civil rights one.

The second picture is of a house on Greenhill Beach, in Wakefield. The owners of the large home built a seawall to try to prevent their property from disappearing. That was legal at the time and was their right — though they may be hastening the erosion of the adjacent properties. But people have walked along this beach as far back as memory of it goes. The blue line is from 2014 surveying. Even then people would have had to climb over the foot of the rock wall to pass by.

At present, at high tide or after a big storm, the only safe place to walk is along the top of the rock pile wall across the house’s yard. It will be a challenge going forward for shorefront properties to find ways to accommodate citizens passing along the shore as the sea advances up and over the land.

The important takeaway is that the shoreline location may be changing, but our constitutional privileges of the shore are not. There are many more locations in Rhode Island with the same dynamic unfolding.

Jim Bedell runs the Rhode Island Shoreline Access Coalition.

EcoRI News: Warmer water, different N.E. fish

--NOAA chart

By ecoRI News staff

See ecori.org

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists recently released the first multi-species assessment of just how vulnerable U.S. marine fish and invertebrate species are to the effects of climate change.

The study examined 82 species off the Northeast coast, where ocean warming is occurring rapidly. Researchers found that most species evaluated will be affected, and that some are likely to be more resilient to changing ocean conditions than others.

“Our method identifies specific attributes that influence marine fish and invertebrate resilience to the effects of a warming ocean and characterizes risks posed to individual species,” said Jon Hare, a fisheries oceanographer at NOAA Fisheries’ Northeast Fisheries Science Center, in Narragansett, R.I., and lead author of the study. “This work will help us better account for the effects of warming waters on our fishery species in stock assessments and when developing fishery management measures.”

The study is formally known as the “Northeast Climate Vulnerability Assessment” and is the first in a series of similar evaluations planned for fishery species in other U.S. regions. Conducting climate change-vulnerability assessments of U.S. fisheries is a priority action for NOAA.

The 82 Northeast marine species evaluated include all commercially managed fish and invertebrate species in the region, a large number of recreational fish species, all fish species listed or under consideration for listing on the federal Endangered Species Act, and a range of ecologically important species.

NOAA researchers, along with colleagues at the University of Colorado, worked together on the project. Scientists provided climate model predictions of how conditions in the region's marine environment are predicted to change in the 21st Century. The method for assessing vulnerability was adapted for marine species from similar work by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to characterize the vulnerability of wildlife species to climate change.

The method tends to categorize species that are “generalists” as less vulnerable to climate change than are those that are “specialists.” For example, Atlantic cod and yellowtail flounder are more generalists, since they can use a variety of prey and habitat, and are ranked as only moderately vulnerable to climate change.

The Atlantic sea scallop is more of a specialist, with limited mobility and high sensitivity to the ocean acidification that will be more pronounced as water temperatures warm. Thus, sea scallops have a high vulnerability ranking.

The method also evaluates the potential for shifts in distribution and stock productivity, and estimates whether climate-change effects will be more negative or more positive for a particular species.

“Vulnerability assessments provide a framework for evaluating climate impacts over a broad range of species by combining expert opinion with what we know about that species, in terms of the quantity and the quality of data,” Hare said. “This assessment helps us evaluate the relative sensitivity of a species to the effects of climate change. It does not, however, provide a way to estimate the pace, scale or magnitude of change at the species level.”

Researchers used existing information on climate and ocean conditions, species distributions and life history characteristics to estimate each species’ overall vulnerability to climate-related changes in the region. Vulnerability is defined as the risk of change in abundance or productivity resulting from climate change and variability, with relative rankings based on a combination of a species exposure to climate change and a species’ sensitivity to climate change.

Each species was evaluated and ranked in one of four vulnerability categories: low, moderate, high and very high. Animals that migrate between fresh and salt water, such as sturgeon and salmon, and those that live on the ocean bottom, such as scallops, lobsters and clams, are the most vulnerable to climate effects in the region.

Species that live nearer to the water’s surface, such as herring and mackerel, are the least vulnerable. Most species also are likely to change their distribution in response to climate change, according to the study. Numerous distribution shifts have already been documented, and the study demonstrates that widespread distribution shifts are likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

ecoRI: 'Nuisance' coastal flooding on the rise

By ecoRI News staff By 2050, much of U.S. coastal areas are likely to be threatened by 30 or more days of flooding annually because of dramatically accelerating impacts from sea-level rise, according to a new National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) study.

The findings appear in a paper entitled “From the Extreme to the Mean: Acceleration and Tipping Points for Coastal Inundation due to Sea Level Rise” and follows an earlier study by the report’s co-author, William Sweet, Ph.D., a NOAA oceanographer.

Sweet and fellow NOAA scientist Joseph Park established a frequency-based benchmark for what they call “tipping points,” when so-called “nuisance flooding,” defined by NOAA as between 1 and 2 feet above local high tide, occurs 30 or more times a year.

“Coastal communities are beginning to experience sunny-day nuisance or urban flooding, much more so than in decades past,” Sweet said. “This is due to sea-level rise. Unfortunately, once impacts are noticed, they will become commonplace rather quickly. We find that in 30 to 40 years, even modest projections of global sea-level rise will increase instances of daily high-tide flooding to a point requiring an active, and potentially costly, response.”

Based on that standard, the NOAA team found that these tipping points will be met or exceeded by 2050 at most of the U.S. coastal areas studied, regardless of sea-level rise likely to occur this century. In their study, Sweet and Park used a 1.5- to 4-foot set of recent projections for global sea-level rise by 2100 — similar to the rise projections of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change, but also accounting for local factors such as the settlement of land, known as subsidence.

Boston could start experiencing nuisance flooding by 2021, and Providence and New London, Conn., a decade later (NOAA) . These regional tipping points will be surpassed in the coming decades in areas with more frequent storms, according to the report. These tipping points also will be be exceeded in areas where local sea levels rise more than the global projection. This also includes coastal areas such as Louisiana where subsidence is causing land to sink below sea level.

NOAA tide gauges show the annual rate of daily floods reaching these levels has drastically increased and are now five to 10 times more likely today than they were 50 years ago.

“The importance of this research is that it draws attention to the largely neglected part of the frequency of these events,” said Earth’s Future editor Michael Ellis in accepting the paper for the online journal. “This frequency distribution includes a hazard level referred to as ‘nuisance‘ — occasionally costly to clean up, but never catastrophic or perhaps newsworthy.”

Ellis also noted that the authors use observational data to drive home the important point that nuisance floods, from inundating seas, will cross a tipping point over the next several decades and significantly earlier than the 2100 date that is generally regarded as a target date for damaging levels of sea-level rise.

He also said the paper raises the interesting question of what frequency of “nuisance” corresponds to a perception of “this is no longer a nuisance but a serious hazard due to its rapidly growing and cumulative impacts.”

The scientists base the projections on NOAA tidal stations where there is a 50-year or greater continuous record. The study doesn’t include the Miami area, as the NOAA tide stations in the area were destroyed by Hurricane Andrew in 1992 and a continuous 50-year data set for the area doesn’t exist.

Based on that criteria, the NOAA team is projecting that Boston; New York City; Philadelphia; Baltimore; Washington, D.C.; Norfolk, Va.; and Wilmington, N.C., will soon make, or are already being forced to make, decisions on how to mitigate these nuisance floods earlier than planned.

In the Gulf, NOAA forecasts earlier than anticipated floods for Galveston Bay and Port Isabel, Texas. Along the Pacific coast, these earlier impacts will be most visible in the San Diego/La Jolla and San Francisco Bay areas.

Mitigation decisions could range from retreating further inland to coastal fortification, or to a combination of “green” infrastructure using both natural resources such as dunes and wetland, along with “gray” manmade infrastructure such as seawalls and redesigned stormwater systems.