Phil Galewitz: What Granite State voters like and don’t

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

HANOVER, N.H.

Health care issues are important to Lana Leggett-Kealey, who works as a genetic genealogist. But on Tuesday, Jan. 23, as she walked out of her polling place at a local high school and into a frigid New England morning, she said she had something bigger on her mind when she cast her vote.

“I want to make sure we have someone competent in the White House,” she said. She wrote in President Joe Biden’s name on her ballot in New Hampshire’s Democratic primary.

The Affordable Care Act’s future is important to Robert Stanhope, a retired bill collector. He said he also wrote in Biden, whose administration has worked to reduce costs under the ACA.

But that wasn’t his motivation for his early-morning visit to the polls. “I’m here to keep Trump out of office,” Stanhope said.

Dave Avery, 61, of Merrimack, N.H., said health care wasn’t on his mind either. He sought to put the former president back in the White House. “Immigration and the economy are my issues,” he said. “We also need more money to stay in our country.”

Voters casting their first ballots in the 2024 presidential election cycle on Tuesday framed health care as a back-burner issue, capping years of political wrangling over Obamacare and a pandemic that strained the nation’s health system.

Donald Trump defeated former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley in the state’s GOP primary, Biden, who did not appear on the ballot due to disagreements over the primary schedule, won the Democratic contest owing in part to a vigorous write-in campaign.

In interviews with more than 50 voters this week in New Hampshire — a state where 95% of residents have health insurance, one of the highest rates in the country — most people said their vote was about Trump, like him or hate him. But health care concerns — about costs, access, and, especially among Democrats, abortion — weren’t far from many voters’ minds.

“I have two daughters and five sisters and a mom, so making sure women’s reproductive rights are protected is important to me,” said Rob Houseman, 60, a town official in Hanover. Worried that Republicans will try to “weaponize health care” instead of ensuring access, he said he voted for Biden.

DJ Annicchiarico, co-owner of United Shoe Repair in downtown Concord, is a registered Democrat who wasn’t planning to vote in the primary and is undecided about voting for Biden in the general election. His main concern is inflation, but he also faults Biden for not controlling health costs. “I don’t like Trump and I don’t like Biden either,” he says.

Many opposed to Trump cited concerns about his fitness to lead, while most Trump voters who spoke with KFF Health News said they supported him for two main reasons: They hoped he would reduce illegal immigration and lower inflation.

Democratic voters were more likely than Republicans to cite heath care as a key issue in the election.

“Oh my, yes,” said Ben Gilson, 90, a retired orthopedic surgeon. “Health care is my No. 1 issue.”

While he said he has excellent coverage and pays little in out-of-pocket costs, he worries many younger people struggle and wants to make sure Obamacare is retained. One of Trump’s earliest promises during his 2016 campaign was to repeal and replace the ACA — a vow he has recently revived in his latest attempt to win the White House.

Elaine Kozma, 73, of New London said health care issues are vitally important to her as a cancer survivor. She said she voted for Haley, a former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, whom she thinks she can trust more than Trump.

In New London, Kate Turcotte, a professor at Colby-Sawyer College, said she voted for Biden to keep Trump out of office — and because she trusts Democrats more to improve health coverage and protect abortion rights.

She said she also worries Trump will try to cut health care for the most vulnerable. “Health care should be a right, not a privilege,” she said.

Elaine Kozma of New London says she voted for Haley as a protest vote against Trump. Kozma is a cancer survivor who says Medicare coverage has been good for her. Health is an issue for her, but she mainly wants to make sure Trump does not get back into office.

Art Sullivan of Hooksett says immigration is his main issue in the primary and that he’s voting for Trump. He says he worries immigrants coming into the U.S. without authorization will affect his children through higher taxes. He says he is happy with his Medicare plan, which covers his bills.

Trump voters frequently cited as a top concern. Republicans have accused Biden of allowing record numbers of immigrants to cross into the U.S. from Mexico.

In Merrimack, Mary Clancy, 69, said she was satisfied with her Medicare coverage and was voting for Trump mainly to secure the southern border.

Kathy Franqui, 54, of Merrimack, said the border and immigration were her main reasons for voting for Trump. But she also said Trump would reduce health costs.

Tim Beauchene, 48, of Hanover, who is a cook at Dartmouth College, said he’s concerned about the rise of prices for medical care, along with other goods and services. His vote for Trump “was more about the economy,” he said. “Prices are so high in the grocery store and for gas.” Prices for regular unleaded in New Hampshire averaged $3.03 a gallon on Tuesday, according to the AAA auto club.

At a coffee shop in Warner, Susan Hencke, 62, said she pays $1,100 a month for health insurance. But she said health care was not among the factors determining how she would vote.

She said having a president who will protect civil rights matters most to her. She was undecided about whom to support.

Both she and her husband, who declined to give his name, said they were concerned about abortion restrictions Trump may impose.

Kathy Franqui of Merrimack voted for Trump because she thinks he will help reduce health costs as well as improve border security.

Sitting outside the coffee shop in the freezing weather was Art Sullivan, 75, of Hooksett, who said immigration was his overriding issue in the election — and why he was voting for Trump.

Asked if he had been personally affected by immigration, he said he was worried his children would have to shoulder the financial burden of people coming into the U.S. without authorization.

“The border is a disgrace,” said Sullivan, who said he’s a registered independent voter and sells swimming pools.

Asked if health care was something he thought about when comparing candidates, he said he had a Medicare Advantage plan that covers his bills and provides access to care.

DJ Annicchiarico, co-owner of United Shoe Repair in downtown Concord, said he is a registered Democrat. But while he prefers Biden on health issues, he is not yet persuaded to vote for him in November.

His main concern is inflation. He said the ACA, which he described as a step in the right direction, had helped lower his insurance premiums but hadn’t controlled health care prices. “Something needs to be done to rein in inflation,” he said.

Annicchiarico said he wants to see health care prices regulated by the federal government and worries Trump would try to repeal the ACA. He noted access is still an issue and said getting a dermatology appointment for his daughter meant waiting eight months.

Ben Gilson of Hanover voted for Biden. “Oh my, yes,” he said when asked if health care was an issue this year in deciding for whom to vote. The retired orthopedic surgeon says he has excellent health coverage but is worried about many people without it. Gilson also worries about GOP efforts to repeal the ACA.

Aalianna Marietta, 21, a college student, said health care was important to her, particularly abortion rights, so she would be voting for Biden. “I am 100% pro-choice, and I cannot see myself voting for someone who is racist and a misogynist,” she said of Trump.

Deb Shope, 57, out walking her dog in Lebanon, said health care is a top issue for her because she works as a clinical social worker and sees how important good health coverage can be. She said she was voting for Biden because she liked how he has tried to help people get coverage and address their mental health care needs.

Shope said it’s hard to look beyond how Trump acts as a person. Asked if she is worried about him getting reelected, she said people shouldn’t worry about things out of their control.

Phil Galewitz is Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter

He had to blast it

Elm Street in Milford, N.H. in 1915

“New Hampshire is called the Granite State, because it is built entirely of granite, covered with a couple of inches of dirt. The New Hampshire farmer does not “till the soil,’’ he blasts it. For nine months of the year he brings in wood, shovels snow, thaws out the pump, and wonders why {Robert} Peary wanted to discover the North Pole. The other three months he blasts, plants, and hopes.’’

— Will M. Cressey (1864-1930), writer, actor and humorist, in his The History of New Hampshire (1920’s)

Depot Square in Bradford, N.H., in 1913

North of the immigration zone?

New Hampshire’s Franconia Range. The state’s, er, rigorous climate is uninviting for some immigrants.

“Immigration, of course, in New Hampshire is - it's not something that you see every day. It's not like talking about it in Texas, where people have a much more explicit sense of it.’’

Evan Osnos (born 1976), American journalist and book author

Climbing Moosilauke: Pride goeth before the fall

On the mountain: From left, college classmates Win Rockwell, Josh Fitzhugh, Chris Buschmann and Bob Harrington.

— Photo by Jane Andrews

Truth be told, I prefer paddling to hiking, and one thing I’ve learned from the former is that sometimes it’s good to go with the flow. So when two classmates from my Dartmouth College days invited me to join them at our 52th reunion (the big 50th, in 2020, was cancelled because of COVID) and hike up to the top of Moosilauke Mountain, in New Hampshire, I said sure, count me in.

I had another, nostalgic reason for going besides friendship and bravado. Thirty three years ago, when my father was 75, he hiked up and down Moosilauke with a little help from his two sons. Both my father and my older brother were also Dartmouth graduates. “If he could do it, so can I,” went the message in my mind. The fact that, at 74, I was a year younger compensated in my mind for the other fact: I have early-stage Parkinson’s disease. (Symptons of Parkinson’s include tremor and instability.)

Now Moosilauke, elevation 4,803 feet, is sometimes called Dartmouth’s Mountain,” partly because the college owns quite a bit of the land surrounding the peak, partly because it used to hold ski races down its flank in the 1920s and 1930s, and partly because it has a timbered lodge at its base that welcomes students, faculty, alumni and sometimes even celebrities alike into what for many is iconic about Dartmouth: its connection to the wilderness of northern New Hampshire. Recently, the lodge has been extensively rebuilt using massive timbers, and, of course, New Hampshire granite.

I met my classmates, Win Rockwell and Bob Harrington, and Bob’s partner, Jane Andrews, at a park-n-ride near my home in Vermont at 7 A.M. and we drove over to the base lodge, arriving at 9.

It was a warm June day, with the sky almost cloudless. I had grabbed a coffee and roll for breakfast on our way, and the lodge had packed us a bag lunch consisting of cheese, tomato, bread, peanut butter and jelly sandwichs and brownies. I had two 8-ounce water bottles. In my knapsack I carried warmer clothing for the top in case I needed it. (In my father’s climb, one obstacle was snow at the top. The temperature in the White Mountains can sometimes rapidly drop 50 degrees at the summits, with wind gusts of 40 miles an hour or more.) It was warm enough for shorts. I had climbing boots but very light socks, which were intended to give my toes more room. (I like the boots but sometimes my toes banged into the leather.) I suffer from peripheral neuropathy in both feet, but the tingling I usually experience had not previously bothered me walking.

After discussion amongst my friends, I also decided to take a pair of bamboo cross-county ski poles to assist in balance and motion if necessary. Many people now hike with poles, some extendable, regardless of age.

We left on the main trail from the lodge at 10 a.m. The straightest route to the summit (the route we took) is about 3.5 miles up the Gorge Brook trail, with an elevation climb of 2,933 feet. Hikers in good condition traveling in dry conditions should be able to make it to the peak and back in about 3 hours, with a 20-minute break at the summit.

As we started our hike, I tried to recall my last outing three and a half decades ago. The trail seemed a bit rockier this time and I didn’t recall hearing the water tumble over rocks in the nearby brook. At first all seemed fine. Gradually, however, I felt more and more as though I was walking in the brook, not because the going was wet but because I was having to step rock to rock rather than walk on soil or gravel. In places the soil had eroded so much that the college (through the Dartmouth Outing Club, I believe) had placed large flat stones in a kind of stairway, with the rises varying from 6 inches to a foot and a half.

We stopped after about a mile to eat some of our provisions and enjoy the view to the north. I felt fine if a bit tired. We were passed periodically by younger hikers, some alone and many with dogs. At about the two-mile mark I began to ask hikers coming down the time to the summit. “Oh, it’s not too far,” was a common response.

At about 2.5 miles in I started having balance issues. Now, though I have Parkinson’s, I had not had before one of the common symptoms, instability. Mostly I have a slight tremor in my right hand and some slurring of speech. I tend to walk slowly with a forward hunch. I’m a former soccer fullback, downhill skier and amateur logger, and I’m still in decent shape. But here on Moosilauke, I found myself losing my balance to the rear. In short, I kept falling backwards! My poles helped a bit, but sometimes I found myself having to take two steps back. Then, in one fall, I slammed my left temple hard into a rock in part of the trail that was mostly boulders.

Now you’ve done it, I said to myself, fearing a subdural hematoma, swelling, loss of consciousness and death. Luckily, my friends came to my rescue, checked my vision and saw no bleeding. I had no headache. We continued, but more slowly, with one classmate walking just behind me. I thought of the old Dartmouth song that refers to its graduates having the granite of New Hampshire “in our muscles and our brains.” It’s a good thing, I thought.

At about the two-mile point of the hike, there is a false summit. You are above the tree line and the view opens up. Solid granite outcroppings replace the big boulders we had been walking on. Thinking that we were close to the top, I exulted until, looking again, I saw another rise ahead. “Is that where we have to go?” I asked wearily. “’Fraid so,” said Win, whose father had hiked all over these mountains as a student at Dartmouth in the 30s. “I think I better turn back,” I responded to the general agreement of my team. It was about 2:30 p.m.

Bob agreed to monitor me down the trail, although that meant he lost his opportunity to reach the summit. The other two, Win and Jane, seemed very fresh and expressed their desire to push on and catch up to us on the way down.

Bob Harrington and Jane Andrews made it to the top.

Now most hikers learn quickly that “down” does not necessarily mean “easier.” While I need to lift 219 pounds (my weight) with each step going up, I need to stop the inertia force of 219 pounds going down. In addition, at least for me, on rocky terrain I fear falling downhill more than I fear falling uphill. Gravity will aggravate the momentum falling downhill, I reason.

For me and Bob, then, the trip to the lodge became slower and slower. My legs were weakening and I was becoming very careful about each step. The routine was the same: Get yourself steady, examine the terrain ahead, identify a landing spot, plant poles, transfer weight to the downhill foot in a kind of leap of faith, say a small prayer when you succeeded, repeat.

At about 4 p.m., Jane and Win caught up with us on their downhill journey. Bob and I were only about a mile into our descent. We were stopping every 100 yards or so to let me rest. The decision was made to send Bob and Jane back to the lodge for possible assistance while Win would try to assist me. (We were joined about then by another Dartmouth graduate and his wife, Rick and Lucie Bourdon, who altered their plans to help both physically and emotionally in what was increasingly becoming an ordeal for all of us.)

It’s worth noting here a word about Moosilauke. When the mountain was first developed, in the early 1900’s, a cabin was built at the peak for overnight lodging. (It burned to the ground in 1942.) To help construct and provision that cabin, a dirt road was constructed to the peak. With the destruction of the cabin, that road got less and less traffic and is now mostly overgrown. You can hike on that road, but it is not much easier than the other trails. You also need to be at the peak or the base lodge to access that “carriage road,” so we had no choice but to go down the way we had come up.

In short, once you climb up on Moosilauke, the only way down is to walk, or be carried. Despite my wish as expressed during the descent, there is no zip line or chair lift for exhausted duffers like me. I stopped and sat on rocks or tree stumps with increasing frequency. (“Josh you are doing fine,” Lucie would say. “You have a team behind you!”) At one point Win and I decided that it was better to bushwack off the trail than struggle rock by rock while on it. At least then when I fell the branches and moss- covered rocks I hit were softer than the rocks in the trail, and saplings sometimes provided handholds to brake my descent.

Thankfully, this was one of the longest days of the year and the weather was clear and mild. Nevertheless, by 7 p.m. it was getting dark and we were still a half mile from the lodge. There was still a steep rocky trail ahead. I stumbled off the trail near the brook that I had heard on the way up. Losing my balance I fell, and could not get up. The muscles in my legs were too tired. After Win (who is probably 60 pounds lighter than me) dragged me to a soft spot off the trail, I remember saying, “You guys will have to figure out what to do. I’m done.” I stretched out, closed my eyes and tried to sleep.

By this point, Lucie and Rick had gone on ahead to report my condition and check on help. It began to rain and Win loaned me a parka. It wasn’t expected to be a cold night, and so I said, “Just get me a tarp and my sleeping bag at the lodge. I’ll just spend the night here!” “No way,’’ said Win.

It was dark by the time that two Dartmouth students, Alex Wells ’22 and Jules Reed ’23, arrived. Both were working in the kitchen at the lodge, but had hiking experience, and they had head-mounted flashlights. After they lifted me by my shoulders, I slung one arm over each of their necks. Then, like some six-legged decrepit spider, or a drunken Rockettes threesome, we inched our day down the trail with each of us simultaneously deciding which rock to step upon. When either of them tired, Win took their place.

Forty minutes later we could see the lights from the lodge, and closer still, the lights from the cabin I was sleeping in. No dinner for me, I told them, just get me to my bunk and bring me a bottle of wine. They did and I collapsed in bed, thankful to have made it down and for the help that made that possible. The next morning I learned that Win had used the lodge’s one telephone (there is no cell service at Moosilauke) to call my wife and leave a message. “First of all, let me tell you that Josh is okay,” he had begun.

Postscript

Decades ago, while in high school, I would occasionally quote Socrates, the Greek philosopher, who had said, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” When I have encountered traumatic moments in my life, I have sought to learn from the experience. This was no different. What caused my collapse on the mountain? Should I ever hope to hike again? Could others learn from my ordeal?

Looking back, I clearly should have prepared more for this hike, by taking some shorter hikes with lesser elevations, by having boots that fit better, by using proper hiking poles rather than old, bamboo cross-country poles, and by having a better breakfast and more robust lunch. I should have taken more water and less cold-weather gear in my backpack.

Maybe with Parkinson’s I should not have gone at all. The stress of the climb certainly exacerbated my instability, and my condition put a big burden on my friends. For them, it turned what could have been a delightful summer hike into a memorable, anxious ordeal. Of course, it also reaffirmed the value of friends and the Dartmouth “family.” I would have stayed on that mountain were it not for my saviors.

I do think that the college shares some responsibility for the episode. While I did not inquire, there were no notices that I saw of trail conditions or warnings that the Gorge Brook trail might be unsuitable for people over the age of 70 or suffering from ambulatory instability. Stating the obvious perhaps would be a caution that climbing the mountain is not the hardest challenge; you still have to get down!

In the years since I last climbed Moosilauke, with my father and brother, the trail to the summit has deteriorated greatly from the flow of rain and melting snow. Rather than relocating the trail, the college has sought to remedy it by making a staircase in many locations This works for those with strong knees, hips and ankles but for those like me, hundreds of 12-inch risers exhaust quite a bit of energy both going up and coming down. A better solution to trail washout might be to deposit 1-or-2-inch crushed stone in the interstices between the larger boulders to create a kind of stone path to the summit. This would be difficult and expensive and certainly change the nature of the hike, but it also would improve accessibility and safety, in my humble opinion. If this is feasible I’d be happy to contribute. I have a debt to repay.

From left, Josh Fitzhugh and Good Samaritans Jules Reed and Alex Wells with me after my misadventure.

John H. (“Josh”) Fitzhugh is a writer, former insurance-company CEO, former newspaper editor and publisher and former legal counsel to two Vermont governors. He lives in Vermont, Florida and on Cape Cod.

Parasite state

Terminal of Manchester-Boston Regional Airport, whose name is aimed at grabbing Greater Boston business.

— Photo by MaxVT

“As part of the regional metro-Boston area, southern New Hampshire offers all the benefits typically associated with major metro areas yet maintains the advantages of being in a truly enterprise-friendly state: access to a world-class workforce, a pro-business, low-tax environment, and a streamlined regulatory environment.’’

— New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu

John O. Harney: Some intriguing N.H. and other indices

“The View from Andrew’s Room Collage Series #8″, by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Monserrat College of Art, Beverly, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Percentage of U.S. counties where more people died than were born in 2021: 73% University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of National Center for Health Statistics data

Number of additional births that would have occurred in the past 14 years had pre-Great Recession fertility rates continued: 8,600,000 University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of National Center for Health Statistics data

Percentage of Americans who told the Annenberg Science Knowledge survey in July 2022 that they have returned to their “normal, pre-COVID-19 life”: 41% Annenberg Public Policy Center

Percentage who said that in January 2022: 16% Annenberg Public Policy Center

Percentage of teenagers who reported that their post-high school graduation plans changed between the March 2020 start of the COVID-19 pandemic and March 2022: 36% EdChoice\

Change during that period in percentage of teenagers who said they planned to enroll in a four-year college: -14% EdChoice

Ranks of “Self Discovery,” “Finances” and “Mental Health” among reasons for change in plans: 1st, 2nd, 3rd EdChoice

Percentage of college students who say they will pay their education expenses completely on their own: 67% Cengage

Percentage who say they have $250 or less left after paying for education costs each month: 46% Cengage

Ranks of “lower tuition,” “more affordable options for course materials” and “lowering on-campus costs, such as housing and meal plan costs” among actions students say their colleges could take to lower education costs: 1st, 2nd, 3rd Cengage

Percentage of Americans who graded their local public schools with an A or a B in 2019: 60% Education Next

Percentage who gave those grades in 2022 after two years of COVID-related disruption: 52% Education Next

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are women: 5% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Black: 4% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Asian: 2% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Hispanic: 6% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Approximate percentage increase in sworn personnel in New Hampshire State Police, from 2001 to 2020: 30% Concord Monitor

Percentage of New Hampshire State Police personnel who are white: 95% Concord Monitor reporting of N.H. Department of Safety data

Percentage of New Hampshire State Police personnel who are men: 91% Concord Monitor reporting of N.H. Department of Safety data

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Too libertarian and irascible?

A Sunday edition of the once much feared and admired Manchester Union-Leader, run for many years by far-right publisher William Loeb (1905-1981). A stepdaughter recently accused him of molesting her.

In high and chilly Dublin, N.H.

“There’s little question that Vermont (particularly Vermont), Maine, Boston, and Cape Cod, are, together, responsible for the New England image. New Hampshire just doesn’t fit in.’’

Judson D. Hale Sr., former long-time editor of Yankee Magazine, in “Vermont vs. New Hampshire,’’ in the April 1992 American Heritage magazine. And yet Yankee has always been based in Dublin, N.H.

Historical coat of arms of New Hampshire, from 1876 — a reminder that the state has a (very short) seacoast.

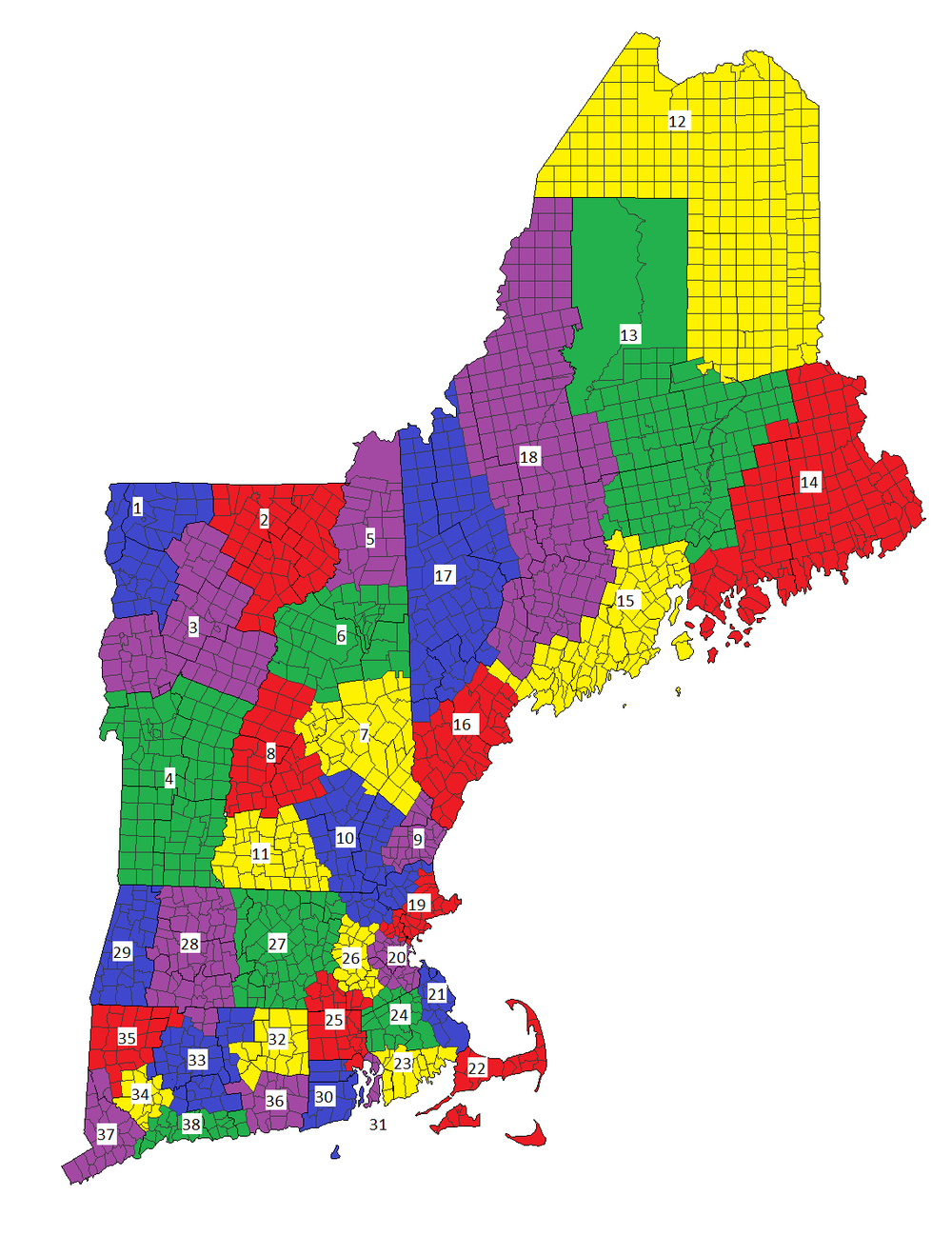

John O. Harney: The state of the New England states as COVID winds down (for now?)

Regions of New England:

1. Northwest Vermont/Champlain Valley

2. Northeast Kingdom

3. Central Vermont

4. Southern Vermont

5. Great North Woods Region

6. White Mountains

7. Lakes Region

8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region

9. Seacoast Region

10. Merrimack Valley

11. Monadnock Region

12. Aroostook

13. Maine Highlands

14. Acadia/Down East

15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay

16. Southern Maine/South Coast

17. Mountain and Lakes Region

18. Kennebec Valley

19. North Shore

20. Metro Boston

21. South Shore

22. Cape Cod and Islands

23. South Coast

24. Southeastern Massachusetts

25. Blackstone River Valley

26. Metrowest/Greater Boston

27. Central Massachusetts

28. Pioneer Valley

29. The Berkshires

30. South County

31. East Bay

32. Quiet Corner

33. Greater Hartford

34. Central Naugatuck Valley

35. Northwest Hills

36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London

37. Western Connecticut

38. Connecticut Shoreline

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

“This Covid-19 pandemic has been part of our lives for nearly two years now. It’s what we talk about at our kitchen tables over breakfast in the morning, and again over dinner at night. It gets brought up in nearly every conversation we have throughout the day, and it’s a topic at nearly every special gathering we attend,” Rhode Island Gov. Daniel McKee noted in his recent 2022 State of the State address.

Indeed, that was a consistent theme among all six New England governors’ 2022 State of the State speeches. As were plugs for innovation in healthcare, especially mental health, housing, workforce development, climate strategies, children’s services, transportation, schools, budgets and, with varying degrees of gratitude, acknowledgement of federal infusions of relief money.

Here are links to the full New England State of the State addresses, highlighting some key points from the beat:

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont’s 2022 State of the State Address

“Our budget invests 10 times more money than ever before in workforce development—with a hyper focus on trade schools, apprentice programs and tuition-free certificate programs where students of all ages can earn an industry-recognized credential in half the time, with a full-time job all but guaranteed.

This investment will train over 10,000 students and job seekers this year in courses designed by businesses around the skills that they need.

This isn’t just about providing people with credentials; this is about changing people’s lives.

A stay-at-home mom whose husband lost his job earned her pharmacy tech certificate in three months and now works at Yale New Haven Hospital.

A man who was homeless was provided housing, transportation, a laptop and training. He’s now a user support specialist for a large tech company.

These are just two examples of opportunities that completely change the course of someone’s life.

We are working with our partners in the trade unions to develop programs for the next generation of laser welders and pipefitters. Building on the amazing partnership between Hartford Hospital and Quinnipiac University, we are also ramping up our next generation of healthcare workers.

I want students and trainees to take a job in Connecticut, and I want Connecticut employers to hire from Connecticut first! To encourage that, we’re expanding a tax credit for small businesses that help repay their employees’ student loans. More reasons for your business to hire in Connecticut, and for graduates to stay in Connecticut—that’s the Connecticut difference.”

Maine Gov. Janet Mills’s 2022 State of the State Address

“It is also our responsibility to ensure that higher education is affordable.

And I’ve got some ideas to tackle that.

First, I am proposing funding in my supplemental budget to stave off tuition hikes across the University of Maine System, to keep university education in Maine affordable.

Secondly, thinking especially about all those young people whose aspirations have been most impacted by the pandemic, I propose making two years of community college free.

To the high school classes of 2020 through 2023—if you enroll full-time in a Maine community college this fall or next, the State of Maine will cover every last dollar of your tuition so you can obtain a one-year certificate or two-year associate degree and graduate unburdened by debt and ready to enter the workforce.

And if you are someone who’s already started a two-year program, we’ve got your back too. We will cover the last dollar of your second year.”

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s 2022 State of the State Address

“We increased public school spending by $1.6 billion, and fully funded the game-changing Student Opportunity Act.

We invested over $100 million in modernizing equipment at our vocational and technical programs, bringing opportunities to thousands of students and young adults.

We dramatically expanded STEM programming, and we helped thousands of high school students from Gateway Cities earn college credits free through our Early College programs.”

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s State of the State Address

“Our way of life here in the 603 is the best of the best.

We didn’t get here by accident—we did it through smart management, prioritizing individuals over government, citizens over systems, and delivering results with the immense responsibility of properly managing our citizens tax dollars.

As other states were forced to buckle down and weather the storm, we took a more proactive approach in 2021. In just the last year, we:

• Cut the statewide property tax by $100 million to provide relief to New Hampshire taxpayers

• Cut the rooms and meals tax

• Cut business taxes—again

• Began permanently phasing out the interest and dividends tax

And while we heard scary stories of how cutting taxes and returning such large amounts of money to citizens and towns would ‘cost too much’, the actual results have played out exactly as we planned, record tax revenue pouring into New Hampshire, exceeding all surplus estimates, allowing us to double the State’s Rainy Day Fund to over $250 million.”

Rhode Island Gov. Daniel McKee’s State of the State Address

“We all know that the economy was changing well before the pandemic. A college degree or credential is a basic qualification for over 70 percent of jobs created since 2008. Although we have made great progress over the last decade, there’s more to do.

Let’s launch Rhode Island’s first Higher Ed Academy, a statewide effort to meet Rhode Islanders where they are and provide access to education and training, that leads to a good-paying job. Through this initiative, which will be run by our Postsecondary Education Commissioner Shannon Gilkey, we expect to support over a thousand Rhode Islanders helping them gain the skills needed to be successful in obtaining a credential or degree.

Having a strong, educated workforce is critical for a strong economy—and Rhode Island’s economy is built on small businesses. Small businesses employ over half of our workforce. As these businesses continue to recover from the pandemic, we know that challenges still persist. That’s why in the first several weeks of my administration, I put millions of unspent CARES Act dollars that we received in 2020 into grants to help more than 3,600 small businesses stay afloat.

My budget will call for key small business supports like more funding for small business grants, especially for severely impacted industries like tourism and hospitality. It will also increase grant funding for Rhode Island’s small farms.

As our businesses deal with workforce challenges, I’ll also propose more funding to forgive student loan debt, especially for health-care professionals, and $40 million to continue the Real Jobs Rhode Island program which has already helped thousands of Rhode Islanders get back to work.”

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott’s State of the State Address

“The hardest part of addressing our workforce shortage is that it is so intertwined with other big challenges, from affordability and education to our economy and recovery. Each problem makes the others harder to solve, creating a vicious cycle that’s been difficult to break.

Specifically, I believe our high cost of living has contributed to a declining workforce and stunted our growth. As we lose Vermonters who cannot afford to live, do business or even retire here, that burden—from taxes and utility rates to healthcare and education costs—falls on fewer and fewer of us, making life even less affordable.

With fewer working families comes fewer kids in our schools. But lower enrollment hasn’t meant lower costs and from district to district, kids are not offered the same opportunities, like foreign languages, AP courses or electives. And with fewer school offerings, it is hard to attract families, workers and jobs to those communities.

Fewer workers and fewer students mean our businesses struggle to fill the jobs they need to survive, deepening the economic divide from region to region.

And for years, state budgets and policies failed to adapt to this reality. …

Let’s start with the people already here and do more to connect them with great jobs.

First, our internship, returnship and apprenticeship programs have been incredibly successful, not only giving workers job experience, but also building ties to local employers. To improve on this work, the Department of Labor assists employers to fill and manage internships statewide and we’ll invest more to help cover interns’ wages.

And let’s not forget about retired Vermonters who want to go back to work and have a lot to offer. I look forward to working with Representative Marcotte and the House Commerce Committee on this issue and may others.

Next, let’s put a greater focus on trades training. And here’s why:

We all know we need more nurses and healthcare workers. And as I previewed with {state} Senator Sanders and {state} Senator Balint earlier this week, I will propose investments in this area. But if we don’t have enough CDL drivers, mechanics and technicians, hospital staff won’t get to work; there will be issues getting the life-saving equipment and supplies we need; and we will see fewer EMTs available to get patients to emergency rooms. If we don’t have enough carpenters, plumbers and electricians, or heating, ventilation, air handling and refrigeration techs, there are fewer to construct and maintain the facilities in our health-care system or build homes for the workers we are trying to attract.”

John O. Harney is the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Specimens of New Hampshire

The New Hampshire State House, built between 1816 and 1819 and designed by architect Stuart Park.

The building was built in the Greek Revival style with smooth granite (natch!) blocks.

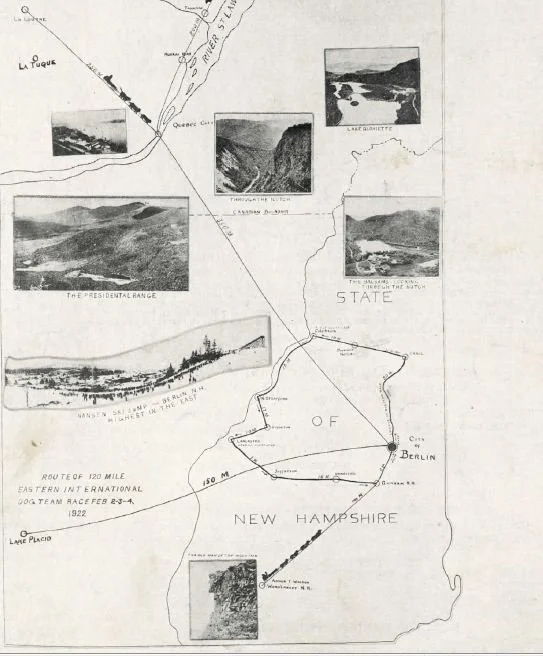

1922 map of New Hampshire published in the bulletin of the Brown {paper} Company in Berlin, N.H.

“I like your nickname, ‘The Granite State.’ It shows the strength of character, firmness of principle and restraint that have characterized New Hampshire.’’

President Gerald R. Ford, in a speech in Concord, New Hampshire’s capital, on April 17, 1975

xxx

“Just specimens is all New Hampshire has,

One each of everything as in a show-case

Which naturally she doesn't care to sell.’’

— From the 1923 poem “New Hampshire,’’ by Robert Frost

The lilac is New Hampshire’s state flower.

Wood for paper and WPA in New Hampshire

“Pulpwood Logging” (oil on canvas, 1941), by Philip Guston (Canadian-American, 1913-1980), in the show “WPA in NH: Philip Guston and Musa McKim,’’ through Jan. 30 at the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, N.H. Pulpwood was used to make paper — a once-large, and heavily polluting (of air and water), industry in the Granite State.

The museum explains:

“In 1941, the famed artist Philip Guston and the {American} poet/painter Musa McKim painted a pair of monumental murals for what at the time was the Federal (aka Forestry) Building in Laconia, N.H. Each measuring 14 feet, the expansive paintings depict sustainable logging and the restoration of New Hampshire forests around the White Mountains. The images were commissioned by the Works Progress Administration to carry out public projects and support artists under the New Deal.

“Although these magnificent murals are of great artistic significance, they have long been forgotten as the original building in Laconia was repurposed. The paintings have been carefully restored by the federal General Services Administration and are back in New Hampshire, where they can now be seen at the Currier Museum of Art….

“The paintings mark important points in the careers of the two artists, who were married to each other. Shortly after completing this mural, Philip Guston gave up realistic painting to focus on Abstract Expressionism; he became a leader of the New York School. Musa McKim focused her career on poetry and writing; her collection Alone with the Moon was published in 1994.”

"Wildlife in the White Mountains” (1941, oil on canvas), by Musa McKim (1908-1992)

Former Federal Building in Laconia, N.H. It now houses a local social-service agency.

Circa 1912

‘The refined grandeur’

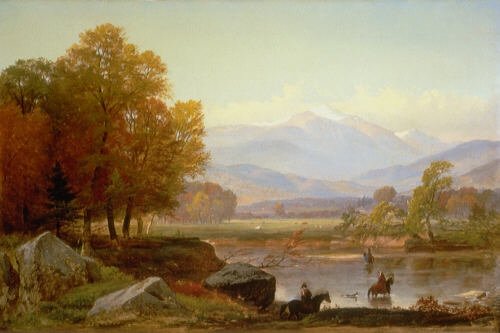

“Mount Washington,’’ by Samuel Lancaster Gerry (1813-1891)

“A visit to New Hampshire supplies the most resources to a traveler, and confers the most benefit on the mind and taste, when it lifts him above mere appetite for wildness, ruggedness, and the feeling of mass and precipitous elevation, into a perception and love of the refined grandeur, the chaste sublimity, the airy majesty overlaid with tender and polished bloom, in which the landscape splendor of a noble mountain lies.”

— Thomas Starr King (1824-1864), an American Universalist/Unitarian minister.

He was influential in California politics during the Civil War, and pressed to keep California rather than splitting off as a separate country.

He vacationed in New Hampshire’s White Mountains in the 1850’s while a minister in Boston and in 1859 published a book entitled The White Hills {Mountains}; their Legends, Landscapes, & Poetry.

Circling makes sense

Rotary sign at a Lowell, Mass., traffic circle. Note the ‘Yield’’ sign.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

like too many other commentators on the $1.1 trillion physical-infrastructure law, have too often failed to note three very important things about, in addition, most famously, to the transportation-related stuff: It would help improve water-supply systems, which are dangerously corroded and outdated in many places and strengthen the electric grid and Internet, including their security, which are all too vulnerable to attacks by the Russians, Chinese, North Koreans and other enemies as well as those extortionists just in it for the money.

We need fewer road intersections with lights and more traffic circles, with landscaping in the middle. The latter have fewer accidents, in part because they slow down drivers where they should be slowed down.\

The Federal Highway Administration reports that traffic circles reduce injury and fatal crashes by 78-82 percent compared to conventional intersections. A typical intersection has 32 conflict points, compared to only 8 at a roundabout.

And, as I discovered last week driving up Route 10 in New Hampshire, they can be quite attractive.

Something for states and localities to consider when it comes to spending federal infrastructure money.

Todd McLeish: Small rodents play important roles in maintaining woodland ecosystems in N.E.

Female White-Footed mouse on sumac bush.

— Photo by Peterwchen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When University of Rhode Island teaching professor Christian Floyd brought students in his mammalogy class to a nearby forest in September to set 50 box traps to capture mice and other small mammals, he was surprised the next morning when more than half of the traps contained a live white-footed mouse.

“I usually expect to catch three or four, and on a good year we’ll get about 12, but you never get 50 percent trap success,” URI’s rodent expert said. “White-Footed Mouse populations fluctuate in boom and bust years, and this year seems to be a boom year.”

Floyd speculated that abundant acorns, recent mild winters and healthy growth of concealing vegetation were probably factors in the unusual numbers of mice captured this year. But whatever the reason for their abundance, healthy mouse populations are a good sign for local forests.

A new study by scientists at the University of New Hampshire concluded that small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks play a vital role in keeping forests healthy by eating and dispersing the spores of mushrooms, truffles, and other fungi to new areas.

According to Ryan Stephens, the post-doctoral researcher at UNH who led the study, all trees form a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Healthy forests are dependent on hundreds of thousands of miles of fungal threads called hyphae that gather water and nutrients and supply it to the trees’ roots. In return, the trees provide the fungi with sugars they produce in their leaves. Without this symbiotic relationship, called mycorrhizae, forests would cease to exist as we know them.

Different fungal species enhance plant growth and fitness during different seasons and under different environmental conditions, so maintaining diverse fungal communities is vital for forest composition and drought resistance, according to Stephens.

But fungal diversity declines when trees die because of insect infestations, fires and timber harvests. That is why the role of small mammals in dispersing mushroom spores is so critical to forest ecology.

To effectively support healthy forests, Stephens said these animals must scatter spores of the right kind of fungi in sufficient quantities and to appropriate locations where tree seedlings are growing. But not every kind of small mammal disperses all kinds of spores, so it’s imperative that forest managers support a diversity of mammal species in forest ecosystems.

“By using management strategies that retain downed woody material and existing patches of vegetation, which are important habitat for small mammals, forest managers can help maintain small mammals as important dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi following timber harvesting” and other disturbances, Stephens said. “Ultimately, such practices may help maintain healthy regenerating forests.”

Distributing mushroom spores isn’t the only important role played by mice and voles in the forest environment. They are also tree planters.

“Almost all rodents cache food — they have a cache of acorns, seeds, maybe truffles, little bits of mushrooms,” Floyd said. “Our oak forests are probably all planted by rodents. They scurry around and dig holes and bury things.”

White-Footed Mice, which Floyd said are the most abundant mammal in Rhode Island, are also voracious consumers of the pupae of gypsy moths.

“For a mouse, gypsy moth pupae are like little jelly donuts; they’re a delicacy,” he said. “The theory is that when mouse numbers are high, they can regulate gypsy moth populations.”

Mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks are also the primary prey of most of the carnivores in the forest, from hawks and owls to foxes, weasels, fishers, and coyotes. These small mammals are a vital link in the food chain between the plant matter they eat and the larger animals that eat them.

Are these small mammals the most important players in maintaining healthy forests? Probably not. Floyd believes that accolade probably goes to the numerous invertebrates in the soil. But this new research on the dispersal of mushroom spores by mice and voles may move them up a notch in importance.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Bill Minter: The United States of places to hide corrupt foreigners' piles of money

For foreign crooks, The Granite State is a place to live free and thrive.

Via OtherWords.org

{Editor’s note: New Hampshire is also a major place to hide ill-gotten gains. Hit this link.}

There are many ways in which the United States is not one country.

I’m not referring to red states versus blue states, or racial or ethnic divisions. What I mean is that the United States, where countless corrupt billionaires and dictators have stashed their loot, is not a single tax haven, but many separate tax havens.

The Pandora Papers, released in October, show that the United States is second only to the Cayman Islands in facilitating illicit financial flows. But it’s not a simple picture.

Each state and territory has its own laws and regulations about financial transactions used for tax evasion or money laundering. And both red states and blue states are destinations for those who seek to hide their money from tax collectors and public scrutiny.

President Biden’s home state of Delaware has long been renowned for its use as a tax haven, beginning in the late 19th Century. Reliably Democratic in national politics, Delaware still ranks at the top among U.S. states providing secrecy for corporations and ultra-high-wealth individuals, both domestic and foreign.

But the Pandora Papers cite ruby-red South Dakota as an attractive destination for billionaires and others seeking to avoid estate taxes.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which led the Pandora Papers investigation, obtained access to the records of the Sioux Falls office of Trident Trust. Among its clients were the family of Carlos Morales Troncoso, former president of Central Romana, the largest sugar plantation in the Dominican Republic — which is notorious for its exploitation of Haitian workers.

South Dakota led the way in providing such trusts, as reported in detail even before the current revelations. But other states, including Alaska, Florida, Delaware, Texas, and Nevada, have followed suit.

The Pandora Papers also document the luxury real estate holdings of Jordan’s King Abdullah. Like many other politicians and oligarchs around the world, King Abdullah owns real estate in many places outside his country. The ICIJ found records of his purchases in London and Washington, D.C., among other cities, as well as three side-by-side mansions in a luxury enclave in Malibu, California.

Bottom line: those seeking to track down the hidden wealth that dictators, criminals, or jet-setting billionaires have lodged in the United States must not limit their efforts to supporting changes in national legislation in Washington, D.C. They must also turn the spotlight on state and local communities around the country.

In February 2017, for example, The Washington Post called attention to the fact that U.S. relations with Gambia and Equatorial Guinea were not just “foreign policy” but also a local story in Potomac, Md.

Ousted Gambian dictator Yahya Jammeh lived at 9908 Bentcross Drive in the D.C. suburb. His counterpart Teodoro Obiang Nguema, who has ruled Equatorial Guinea since his successful coup in 1979, still owns the house at nearby 9909 Bentcross Drive.

The effects of these mechanisms to hide assets from taxation and siphon money to the rich are felt at all levels — from the failure to address global crises such as climate change and the pandemic to gross inequality in housing and other essential needs.

Exposing those mechanisms and building the political will to curb illicit financial flows requires action not only in national capitals and global institutions, but also in all the jurisdictions where wealth is hidden. Nowhere is this more true than for the United States.

In Washington, this message from the Panama Papers is beginning to be heard if not yet followed.

A recent Washington Post editorial read “States must stop letting the ultrawealthy dodge taxes — and the law.” Despite the limited progress on national legislation, that fight can begin in states across the country — probably including yours.

William Minter is the editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin and an advisor to the U.S.-Africa Bridge Building Project. This op-ed was adapted from Africa Is a Country.

Go back where you came from

Junction signage in Newfields, N.H., as seen in 2005 (left) and 2019. It’s a beautiful small town to find yourself in, even if you’re lost. See below.

"We don't enjoy giving directions in New Hampshire. We tend to think if you don't know where you're going, you don't belong where you are."

— John Irving (born 1942), novelist who was born and raised in Exeter, N.H.

Squamscott Street in Newfields

“Newfields, New Hampshire ‘‘(1917), by Childe Hassam, at the Princeton University Art Museum

Sara Jean-Francois: Attacks on Critical Race Theory suppress racial liberation and free speech

Rally on the Boston Common on May 31, 2020 after the murder of George Floyd

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

When I was in elementary school, history happened like this: The world was fighting, the Civil War happened, Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves and then everything was happy and free, and the U.S. was the place to be. Now obviously that is a gross exaggeration of the facts. But it’s not untrue about what we as role models, educators, parents and guardians chose to disclose to children about the historical legacy of race and, thus racism, in the U.S.

As a Black girl growing up in a wide variety of neighborhoods, but almost always attending a predominantly Black and ethnically diverse school, it strikes me as inherently odd that even as K-12 schools and higher education begin to educate an increasingly diverse set of students, we can simultaneously remain complicit in the concealment of history as it is, not as we have decided to rewrite it.

Last year, shortly after the murder of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and so many others, it seemed as if the world had finally opened their eyes to the everyday reality and fears of Black America. And yet, just after the anniversary of these murders, we see state legislation in the headlines of various news sites attacking Critical Race Theory (CRT) and actually proposing legislation that would ban teaching history, as it is commonly accepted to be true. We cannot deny that woven into the narrative of U.S history is the history of systemic racism and other oppressions.

“Divisive” concepts?

Many have coined the term “divisive teaching” to describe teaching from what would be considered a culturally relevant and historically accurate account of race and racism in the U.S.

In Iowa, legislation has been passed that would explicitly forbid teaching of systemic racism or sexism. And Iowa is not alone. Earlier this year, Oklahoma banned CRT, causing a chain reaction of lost course offerings for students who want to learn about the true history of race in the U.S. In New England, the New Hampshire legislators approved a bill that would ban the teaching of “divisive concepts,” including topics of inherent racism, sexism or oppression, whether consciously or unconsciously. (Similar bills have been introduced in Maine and Rhode Island.)

The Iowa, New Hampshire and Oklahoma legislation attack the discussion of systemic racism head-on, leaving the potential for an entire generation of young people to grow up with the same implicit bias, bigotry and stereotypes that have led to the death of so many Black Bodies already, including George Floyd. They are just three examples of how legislative attacks on Critical Race Theory are directly trying to use politics to attack racial progression. It raises the question, will there ever be a post-racial society?

For the past year, as so much of the world shouted “Black Lives Matter,” whether at protests, through statements of solidarity, posting little black boxes on Instagram, T-shirts, or supporting Black-owned businesses, we all felt the weight of racism in the air. We saw how racism breeds real-life consequences, and for Black people, that can mean death.

Yet here we are, concerned with the state of academic freedom, rather than about what it means for the future generation of Black bodies in the U.S. Somewhat ironically, news reports about these pieces of legislation follow the official national recognition of Juneteenth as a federal holiday. This irony begs the question: Is America moving forward toward a more racially equitable society or is performative politics the new norm as we face yet another inflection point in history?

What about antiracism?

If states are allowed to ban an entire body of research, theories and the models and pedagogy that come from this work (already left out of everyday teachings) how can the U.S. claim we learned anything about “antiracism” in the past year?

How can higher claim to care about Black life, when academic freedom is considered far more sacred? The anti-CRT legislation undoubtedly will uphold the inherently white-centric teachings that have been established as our common educational standard. The historical and present relationship that the U.S has with racism, and other oppressions within and outside higher education, seems to be more protected and guarded than the Black lives that are constantly being attacked and killed.

Bell hooks posits that “education is a practice of freedom” and yet education and, thus the freedom it gives everyone, not just Black people, is also being attacked. Who will suffer the most? And so I ask, Why did George Floyd become martyr to a cause nobody is listening to anymore?

If you ask me, the aforementioned anti-CRT legislation is not only an attack on academia and free speech, but also a direct suppression of racial liberation and consequently any racial progression moving forward. It is time that politicians, activists and educators alike take a divisive and definitive stance and decide whether the academy, and whether this democracy, will follow a path of antiracism or continue to be passively racist.

Sara Jean-Francois is assistant director of NEBHE’s Regional Student Program, Tuition Break. She recently earned her master’s degree in public policy from Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, where she conducted significant research on race-conscious campuses and issues of equity and inclusion within higher-education policy.

Phil Galewitz: Biden seems in no hurry to allow import of Canadian drugs

U.S. and Canadian customs officers

The Biden administration said Friday it has no timeline on whether it will allow states to import drugs from Canada, an effort that was approved under former President Trump as a key strategy to control costs. {Many New Englanders, especially those in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, have long sought to be able to easily get pharmaceuticals from Canada for obvious reasons of price and proximity.}

Six states have passed laws to start such programs, and Florida, Colorado and New Mexico are the furthest along in plans to get federal approval.

The Biden administration said states still have several hurdles to get through, including a review by the Food and Drug Administration, and such efforts may face pressures from the Canadian government, which has warned its drug industry not to do anything that could cause drug shortages in that country.

The Biden administration said the lawsuit was moot because it’s unclear when or if any states would get an importation plan approved.

Drug importation has been hotly debated for decades, with many states and advocates believing it would help lower the prices Americans pay while the drug industry contends it would undercut the safety of the U.S. drug supply. Critics note most brand-name drugs sold in the U.S. are manufactured abroad.

Friday’s court filing had been eagerly anticipated, as it was the first time the Biden administration weighed in on the issue. Promises to curb high drug prices have been a standard sound bite of political campaigns, and importation enjoys broad public support. Supporters of importation range the political spectrum from progressive Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) to Florida’s conservative Republican governor, Ron DeSantis. They argue Americans should not pay more for drugs than consumers in other countries.

Rachel Sachs, a health law expert at Washington University, in St. Louis, said the rhetoric in the court filing is probably “disheartening” to DeSantis and other supporters hoping that states’ importation programs would be approved soon. “They are laying out that there is no time limit on the FDA and there are many steps that states have to undergo before approval,” she said.

Supporters of drug importation say they still have hope, especially if the court agrees to the administration’s effort to throw out the suit.

“While articulating possible hurdles that may prevent state drug importation programs from moving forward, the Biden administration’s motion to dismiss PhRMA’s lawsuit keeps alive opportunities for more Americans to benefit from drug importation,” said Gabriel Levitt, president of Pharmacychecker.com, which verifies online foreign pharmacies for customers.

Importing drugs from Canada, where government controls keep prices lower, has been debated for decades in the U.S. A 2003 federal law gave the executive branch permission to do it, but only if certified as safe and cost-effective by the HHS secretary. Then-HHS Secretary Alex Azar announced in September that he would become the first to do that, and the department issued its rule in October.

Florida, Colorado, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico and Vermont are pursuing efforts to import drugs.

PhRMA filed its suit in November in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. In the court filing late Friday, the Biden administration said the FDA could reject state importation plans for many reasons, including safety concerns and lack of significant savings for consumers.

In an e-mailed statement, PhRMa spokesperson Nicole Longo said: “We continue to believe the Trump Administration violated federal law when it finalized its rule permitting state-sponsored drug importation from Canada without proper certification and, in doing so, putting the health and safety of Americans in jeopardy.”

Canada has opposed efforts to send its drugs to the United States, fearing that it could exacerbate shortages there. Last year, Canadian health regulators warned companies against exporting any drugs that could lead to shortages.

During the presidential campaign, Joe Biden supported drug importation. His HHS secretary, Xavier Becerra, voted for the 2003 Canadian drug importation law as a member of Congress.

In most circumstances, the FDA says it’s illegal for individuals to import drugs for personal use.

Yet, for nearly 20 years, storefronts in Florida have helped people buy drugs online from pharmacies in Canada and other nations at typically half the U.S. price. The FDA has periodically cracked down on the operators but has allowed the stores to stay open.

The Florida legislature in 2019 approved the state drug importation program, and the state submitted its proposal to the federal government last year. While DeSantis has boasted of the strategy at news conferences in the retiree-heavy community of The Villages, the state program would have little direct effect on most Floridians.

That’s because the state effort is geared to getting lower-cost drugs to state agencies for prison health programs and other needs and for Medicaid, the state-federal health program for the poor. Medicaid enrollees already pay little or nothing for medications.

Florida has identified about 150 drugs — many of them expensive HIV/AIDS, diabetes and mental health medicines — that it plans to import. Insulin, one of the most expensive widely used drugs, is not included in the program.

DeSantis said the importation plan would save the state between $80 million and $150 million. The state has a $96 billion budget, he said.

“It’s been under review enough,” DeSantis said Friday, hours before the Biden administration’s court filing. “We have followed every regulation. We’ve met every requirement that we were asked to meet, and we want now to be able to get this final approval so that we can finally move forward.”

Christina Pushaw, a spokesperson for DeSantis, said the governor was disappointed by the Biden court filing.

“Governor DeSantis calls on the Biden Administration to step out of the way of innovation and act immediately to approve Florida’s plan that provides safe and effective drugs to drive down prescription costs,” she said in an email to KHN.

The governor appeared at LifeScience Logistics in Lakeland, Florida, where state regulators worked with the company to construct an FDA-compliant warehouse to process pharmaceuticals from Canada.

“We’re ready, willing and able, and I think that this could be really, really significant,” DeSantis said.

He said the warehouse could begin receiving drugs from Canada within 90 days if the state were to get approval from Washington.

LifeScience Logistics officials said they are working with Methapharm Specialty Pharmaceuticals, which has offices near Toronto and Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to act as its Canadian wholesaler. Quality checks would be done on the drugs in Canada and again in Florida, said Richard Beeny, CEO of LifeScience Logistics.

LifeScience has begun early talks on negotiating prices with drug manufacturers that would deliver medications to Methapharm, which in turn would send drugs to the Lakeland warehouse. “There is broad interest in the program,” Beeny said about drug companies wanting to participate. “But the pending suit is a bit of a roadblock, so we have to wait and see how that pans out.”

Unlike Florida’s plan, Colorado’s Canadian importation program would help individuals buy the medicines at their local pharmacy. Colorado also would give health insurance plans the option to include imported drugs in their benefit designs.

Mara Baer, a health consultant who has worked with Colorado on its proposal, said the Biden decision leaves open the question of whether state importation plans might eventually be approved. “HHS could have let the rule fall and they did not, which is important given the challenges facing Congress in moving major drug pricing reform in the short term,” she said.

Phil Galewitz is a journalist for Kaiser Health News

Campobello Island is an exclave of Canada’s Province of New Brunswick , but with land access to the mainland being only to Maine.

Llewellyn King: America’s rare-earth vulnerability

Refined rare-earth oxides are heavy gritty powders usually brown or black, but can be lighter colors as shown here

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A world commodities rebalancing is underway, and China is in a position of dominance. Take lithium, where China is a major processor and battery manufacturer; cobalt, where China has dominated the supply chains; and rare earths, where China has an almost total monopoly. Taken together, these three commodities are key to the future of alternative energy, electric vehicles, mobile phones, and even headphones.

Having stated that he was “fervently Sinophile,” British Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the House of Commons recently called lithium deposits in England’s rugged southwestern county of Cornwall “the Klondike” of lithium. Johnson is known for his grandiloquence, but he knows about the importance of lithium in the age of the lithium-ion battery, and a big lithium mine will open in Cornwall in 2026.

This kind of economic activity points to the re-evaluation and rebalancing of the world’s vital, non-agricultural commodities, reflecting the need for new raw materials for national survival as the demands of technology have changed.

The rare earth elements — there are 17 of them but only four are in demand — are the great multipliers of the modern electronic age. I have seen how this works with the equivalent of a refrigerator magnet. A traditional magnet has a slight pull toward the metal surface. Try it with a magnet that has been enhanced with one of the rare earths, neodymium, and you will find the attraction to the metal of the refrigerator so strong that the magnet will fly out of your hand — and it will take a muscular tug to remove it.

Enhanced magnetism is what makes wind turbines economically feasible. Wind turbines wouldn’t produce enough electricity to make them economical without that multiplier.

The problem is that 95 percent of the rare earths now mined and processed come from China.

This gives the Chinese the ability to choke off the West’s economies while the struggle to produce the vital elements elsewhere (and they are well distributed throughout the Earth’s crust) is mounted.

David Zaikin, a Ukrainian-born Canadian citizen working in London, knows as much about the world resource line-up and China’s influence as anyone. He is the CEO of Key Elements Group, and an alumnus and founder of the Mining Club at the London Business School.

“China is out there and is trying to win every race globally. The West must do everything it can to subvert its efforts and find alternative nations to work with,” Zaikin says.

“The good news is that there are friendly nations like Canada, Australia, and India that are naturally very rich in rare earths. They are well-positioned to bridge the gap in potential rare earths shortages, or in the event those are weaponized by the PRC,” he says, “The bad news is that it takes a long time to begin commercial production, and the right time to start was yesterday.”

The Mountain Pass mine, in the Mojave Desert in California, is in production after a hiatus. But that doesn’t mean much in terms of our Chinese dependence. The production from California is shipped to China for processing and then shipped back to the United States. The mine has also been financed by the Chinese.

The inhibition to mining for rare earths, as John Kutsch, executive director of the Thorium Energy Alliance, explains, is thorium, which isn’t a rare earth element, but which is found in conjunction with rare earths, especially in the United States.

Thorium is a fertile nuclear material and is classified as such by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the International Atomic Energy Agency, so miners have to account for it, and it has to be stored and disposed of as nuclear waste.

Until a national thorium bank is established, as supported by Kutsch and his group, we will be looking elsewhere.

Zaikin says, “As the West pursues green policies and becomes more independent of imported oil, it will reduce the influence that the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] and other oil-producing nations have on domestic and international policies.”

He adds, “However, by moving from oil into renewable energy, the West increasingly finds itself at the mercy of China. This is why it is crucial that the West includes nuclear power in its green vision of the future, in order to avoid the weaponization of energy by hostile powers.”

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: The technique used to purify rare-earth minerals was developed at the beginning of the 20th Century by chemist Charles James (above) at the University of New Hampshire.

New England, especially New Hampshire, has rocks with rare earth elements

Todd J. Leach: Colleges must figure out how to survive after the pandemic

At the Keene (N.H.)State College campus, left to right: President's House, Morrison Hall, Parker Hall

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Colleges and universities were hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis. The American Council on Education (ACE) estimated a total impact of $120 billion in a recent letter to legislators. That number reflects both direct expenses and lost revenues. It is easy to identify the direct expenses associated with testing, cleaning, PPE, remote learning technology and improved ventilation systems. But the lost revenues, while harder to measure, were just as impactful.

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reports a 22% drop in students going directly from high school to college. With an estimated 30 million people out of work, part-time enrollments and lower-priced community colleges were affected sharply. Four-year institutions may have experienced smaller overall enrollment drops than the community colleges, but the combination of fewer students in residence halls and significantly higher costs associated with those students who did choose to live on campus, had a dramatic negative impact on auxiliary revenues.

Given the gloomy financial realities of both 2019 and 2020 it may be somewhat surprising how few colleges permanently closed their doors as a result. It might be tempting to believe the worst of the financial woes for higher education will soon be over once the vaccine brings an end to the pandemic, but that sigh of relief would be premature.

The federal relief provided to higher education was ultimately less than a third of what the ACE was requesting. Many states augmented that aid further with state-allocated CARES funding, but there remains a financial gap that institutions have to address in other ways. Many of the approaches used to cover that gap will have lasting impact and make the future for many colleges more challenging than it already was.

Tapping into reserves or endowments, furloughs and layoffs, increases in deferred maintenance, salary cuts and freezes, and other short-term fixes may have helped institutions manage through the crisis but they will have to be made up for at some point. It may turn out that COVID has a delayed impact on the survivability of many institutions that relied on these short-term measures as opposed to addressing more substantially those structural costs that better support long-term sustainability in the face of continuing demographic declines and intensifying competition.

Already squeezed

Higher education was already in the midst of challenging times and COVID’s biggest impact may be how it accelerates the need for structural change and the rethinking of the student experience. The long-term demographic picture, as forecast by Nathan Grawe among others, shows many years of declining enrollments ahead, capped off at the end of the 2020s by, what Grawe himself described in a January 2018 interview with Inside Higher Ed, as a “free fall.” For those of us in the Northeast, the predicted loss in four-year college going students is about 4,000 per year for the next decade.

Institutions that thought they could weather the predicted 1% to 2% annual demographic decline as they incrementally rethought and restructured over the course of several years may no longer have the luxury of time. In fact, those institutions that solely focused on the short-term challenge of COVID may have weakened their ability to respond to the long-term threats. The loss (or disenfranchising) of key talent, the spending of strategic reserves, and the increased backlog of deferred maintenance will all make it much more challenging to make the bold strategic changes and investments it will take to compete in a post-COVID environment.

It may be many years before families fully recover economically, and it is highly likely that states will have fewer funds available for higher education going forward, at least without federal level support. These financial constraints will make it highly unlikely that institutions will be able to make up for the COVID impacts by raising tuition or advocating for higher levels of state support. In fact, the discounting wars can be expected to accelerate, rather than cease, as institutions compete more heavily over a smaller pool students simultaneously facing deeper financial challenges.

Some leaders may find comfort in the fact that many of their peer institutions will be in the same situation and that some shakeout may help address the supply side of the equation, but that is not likely to provide any immediate post-COVID relief. It might also be tempting to believe that the massive migration to remote learning that was necessitated by the pandemic has now jumpstarted a new revenue stream that will carry institutions into the future. The reality is that very few institutions that served a residential population with remote technology have attracted a truly online audience, and they are not likely to, without substantial investment in marketing, extended-hour support services and instructional design. The “Field of Dreams” approach no longer works in a saturated online market and it will take more than streaming lectures or putting classes on the latest LMS to be competitive in online markets.

While higher education may be facing precarious times, the value and need for it has never been greater, and surely, there will be institutions that thrive post-COVID. According to Grawe’s demographic analysis, we can expect highly selective institutions to continue to attract students, and even experience higher demand. I don’t believe the COVID crisis has any particular impact on this prediction. For small and regional institutions, however, I believe the COVID crisis has brought an imminent shakeout closer to the forefront for all the reasons identified above. Nonetheless, post-COVID will also be a period of opportunity for those institutions that have either incorporated long-term plans into their COVID decisions or are prepared to move beyond incremental change and move rapidly towards a rethink of both costs and the student experience.

Short-term cutting vs long-term investment

In an ideal situation, institutions would have already begun planning for long-term cost restructuring prior to the pandemic and, therefore, have simply accelerated those plans, rather than needing to take short-term cost-cutting measures that hinder long-term investment and success. However, for those institutions that had not begun addressing their cost structures, the urgency to do so should be strategic and immediate. Not all the competitors that emerge from the pandemic are going to be in the same place, and those that address their actual cost structure will have the ability to further lower price or, just as importantly, redirect dollars to initiatives that will have an impact on retention and enrollment.