David Warsh: Eating Instagram; McKinsey and OxyContin scandal

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

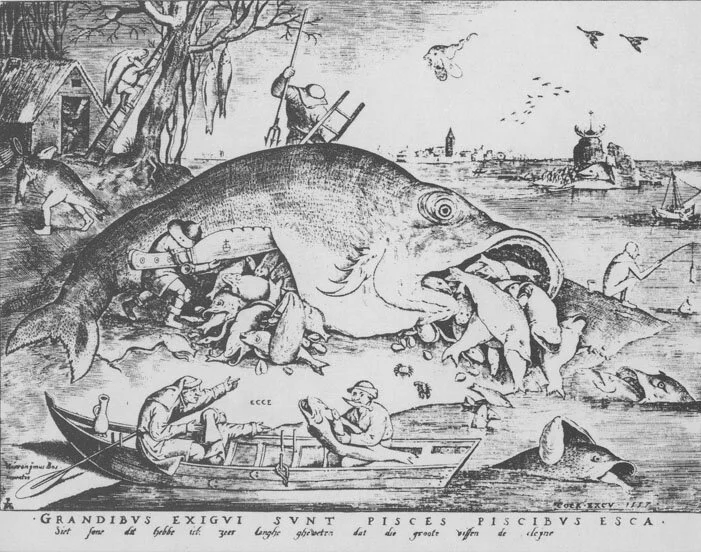

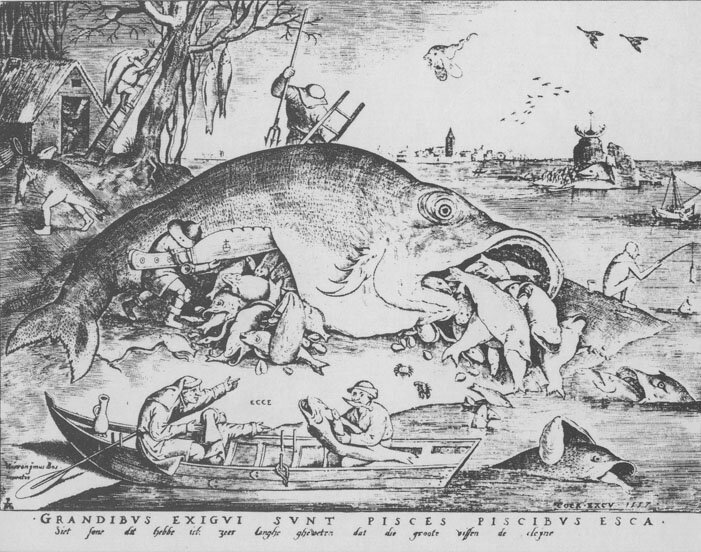

I was as surprised as anyone when a panel of prominent judges earlier this month chose No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sara Frier, of Bloomberg News, as the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year, so I ordered it. The publisher, Simon & Shuster, was surprised, too: the book has not yet arrived. So I re-read FT staffer Hannah Murphy’s review from last April.

The book sounds absorbing enough: how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom agreed to sell his start-up for $1 billion over a backyard barbecue at Mark Zuckerberg’s house and then watched in distress as Facebook bent the inventive photography app to purposes of its own. He finally walked away from the company he started, an enterprise that Frier called “a modern cultural phenomenon in an age of perpetual self-broadcasting” brought low by Facebook’s quest for global domination.

FT editor Roula Khalaf praised the book for tackling “two vital issues of our age: how Big Tech treats smaller rivals and how social-media companies are shaping the lives of a new generation.” In a beguiling online profile last summer, Frier explained how “everything changed” for technology reporters covering social media after the 2016 presidential election. Remembering the embrace-extend-extinguish tactics pioneered by Microsoft, antitrust authorities will also want to take a look.

There is, however, a larger issue about the contest itself. Given the temper of the times, I had thought either Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, or Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, by Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School, powerful books of unusual gravity, might capture the blue ribbon. Both specifically criticize a major McKinsey client, Purdue Pharma, and both vigorously reject the market fundamentalism that often has been imputed to the values of the secretive firm in recent decades – “shareholder value” as the only legitimate compass of corporate conduct and all that.

Granted, the prize is said by its sponsors to reward “the most compelling and enjoyable insight into modern business issues” of a given year. Previous panels have interpreted their instructions in a wide variety of ways. A McKinsey executive last year joined the judging panel. I wondered if the other members, none of them strangers to McKinsey’s lofty circles, had successfully argued to include the two critical books on the short list, before selecting a title more narrowly about “modern business issues” to avoid embarrassment to the sponsor. The awarding of literary prizes as it actually works on the inside is sometimes said to be very different from how it may look from the outside.

An OxyContin pill

Whatever the case, the judges could not have known about the news that broke the day before their decision was announced. The New York Times reported that documents released in a federal bankruptcy court had revealed that McKinsey & Co. was the previously unidentified-management consulting firm that has played a key role in driving sales of Purdue’s OxyContin “even as public outrage grew over widespread overdoses” that had already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In 2017, McKinsey partners proposed several options to “turbocharge” sales of Purdue’s addictive painkiller. One was to give distributors rebates of $14,810 for every OxyContin overdose attributed to pills they had sold. Purdue executives embraced the plan, though some expresses reservations. (Read The New York Times story: the McKinsey team’s conduct was abhorrent.) Spokesmen for CVS and Anthem, themselves two of McKinsey’s biggest clients, have denied receiving overdose rebates from Purdue, according to reporters Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe.

Moreover, after Massachusetts’s attorney general sued Purdue, Martin Elling, a senior partner in McKinsey’s North American pharmaceutical practice, wrote to another senior partner, “It probably makes sense to have a quick conversation with the risk committee to see if we should be doing anything” other than “eliminating all our documents and emails. Suspect not but as things get tougher there someone might turn to us.” Came the reply: “Thanks for the heads-up. Will do.” Elling has apparently relocated his practice from New Jersey to McKinsey’s Bangkok office, The Times’s reporters write.

Last week The Times reported that McKinsey & Co. issued an unusual apology for its role in OxyContin sales and vowed a full internal review. Sen. Josh Hawley (R.- Mo.) wrote the firm asking if documents had been destroyed. “You should not expect this to be the last time McKinsey’s work is referenced,” the firm wrote in an internal memo to employees. “While we can’t change the past we can learn from it.”

Another rethink is for the FT. The newspaper started its award in 2005, with Goldman Sachs as its co-sponsor. Tarnished by the 2008 financial crisis and the aftermath, the financial-services giant bowed out after 2013 and McKinsey took over. The enormous consulting firm is famous mainly for the anonymity on which it insists, but the Purdue Pharma scandal isn’t the first time that McKinsey has been in the news recently, especially for its engagements abroad, in Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. A thorough audit of its practices, reinforced by outside institutions, is overdue. In an age of mixed economies and transparency, McKinsey’s business model of mutually-contracted secrecy between the firm and the client seems outdated

Why the need for sponsorship? It would seem to be mainly a form of cooperative advertising. The cash awards to authors are lavish: £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 to each of five finalists, undisclosed sums to the judges, publicists and for advertising. That makes McKinsey’s investment a spectacular bargain, but it is something of a poisoned chalice for the FT.

The prize’s reputation as recognizing entertaining writing about important business topics is well established. Why not dispense with the money and influence? Who knows what McKinsey does and for whom? Isn’t trustworthy filtering of information the very essence of the newspaper’s business?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

Chris Powell: Plenty of voter fraud in Bridgeport; piling on Purdue Pharma

Iranistan, the residence of P.T. Barnum, in 1848

According to Connecticut Secretary of the State Denise Merrill, the Nutmeg State has too little voter fraud to worry about. But she doesn't really know, because until last week few people had ever seriously looked.

But last week Connecticut's Hearst newspapers looked into the extraordinary level of absentee voting in Bridgeport's recent Democratic mayoral primary election, in which the challenger, state Sen. Marilyn Moore, won on the voting machines but was defeated as Mayor Joe Ganim overwhelmingly carried the absentee ballots.

The Hearst investigation found that fraud was extensive among its limited sample of voters. Ineligible people -- including people who were not registered to vote, people who were not Democrats, and felons and parolees -- received and cast absentee votes. Elderly people were coerced or pressured to complete absentee ballots for the mayor by Ganim supporters who came to their homes. Absentee ballots were sent to people who did not request them. Record-keeping by Bridgeport election officials is sloppy, maintaining incorrect birthdates for some voters and mistaken receipt dates for absentee ballots.

Secretary Merrill has forwarded the Hearst report to the state Elections Enforcement Commission and asked it to investigate because her office lacks the commission's powers. But the secretary should be chastened by what already has come out, for she has been advocating legislation to deny public access to voter registration data

With her legislation Merrill claims to be supporting individual privacy. But voters are not entirely private citizens, for they hold the most basic public office -- elector -- an office established by the state Constitution. Nobody has to become an elector. You volunteer, and election fraud cannot be detected by the public or news organizations unless the names, addresses, and birthdates of electors are as public as they long have been in Connecticut.

Since, as her legislation signifies, the secretary denies the possibility of voter fraud, the law should not hinder the press and public in detecting it as the Hearst papers have just done.

* * *

PILING ON PURDUE PHARMA: If there was an award for piling on, Connecticut Atty. Gen. William Tong would be a leading contender. Practically every day he announces a lawsuit his office is joining to challenge some policy of the Trump administration.

Those policies may be questionable but it is also questionable how much Tong's office is really doing with the lawsuits beyond providing pro-forma endorsements that get publicity for him.

Tong has worked up his greatest indignation for the lawsuit he has joined with many states against Stamford-based Purdue Pharma, manufacturer of the painkiller OxyContin, to which many people have gotten addicted, many of them dying from their addiction. Tong wants the company liquidated and the proceeds somehow distributed to the drug's supposed victims.

But the country's worsening addiction problem long preceded OxyContin, and nobody could have gotten addicted to it if the U.S. Food and Drug Administration hadn't approved it 24 years ago and if thousands of doctors had not prescribed it too heavily to their patients. The FDA and those doctors bear the immediate responsibility for abuse of the drug, not the manufacturer, since from the beginning OxyContin has been a controlled substance.

Of course suing those who uncontrolled the drug would be a tougher and fairer fight for any attorney general who enjoys piling on.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Mass. lawsuit unveils aspects of how the Sackler family reaped a vast fortune off OxyContin

The Sackler family, famously obsessed with raising their social status, have given most of their charitable gifts to already rich elite institutions. Here, for example, is the Sackler Building at Harvard.

By Christine Willmsen, WBUR and Martha Bebinger, WBUR

BOSTON

The first nine months of 2013 started off as a banner year for the Sackler family, owners of the pharmaceutical company that produces OxyContin, the addictive opioid pain medication. Stamford, Conn.-based Purdue Pharma paid the family $400 million from its profits during that time, claims a lawsuit filed by the Massachusetts attorney general.

However, when profits dropped in the fourth quarter, the family allegedly supported the company’s intense push to increase sales representatives’ visits to doctors and other prescribers.

Purdue had hired a consulting firm to help reps target “high-prescribing” doctors, including several in Massachusetts. One physician in a town south of Boston wrote an additional 167 prescriptions for OxyContin after sales representatives increased their visits, according to the latest version of the lawsuit filed Thursday in Suffolk County Superior Court in Boston.

The lawsuit claims Purdue paid members of the Sackler family more than $4 billion between 2008 and 2016. Eight members of the family who served on the board or as executives as well as several directors and officers with Purdue are named in the lawsuit. This is the first lawsuit among hundreds of others that were previously filed across the country to charge the Sacklers with personally profiting from the harm and death of people taking the company’s opioids.

WBUR along with several other media sued Purdue Pharma to force the release of previously redacted information that was filed in the Massachusetts Superior Court case. When a judge ordered the records to be released with few, if any, redactions this week, Purdue filed two appeals and lost.

The complaint filed by Massachusetts Atty. Gen. Maura Healey says that former Purdue Pharma CEO Richard Sackler allegedly suggested the family sell the company or, if they weren’t able to find a buyer, to milk the drugmaker’s profits and “distribute more free cash flow” to themselves.

That was in 2008, one year after Purdue pleaded guilty to a felony and agreed to stop misrepresenting the addictive potential of its highly profitable painkiller, OxyContin.

At a board meeting in June 2008, the complaint says, the Sacklers voted to pay themselves $250 million. Another payment in September totaled $199 million.

The company continued to receive complaints about OxyContin similar to those that led to the 2007 guilty plea, according to unredacted documents filed in the case.

While the company settled lawsuits in 2009 totaling $2.7 million brought by family members of those who had been harmed by OxyContin throughout the country, the company amped up its marketing of the drug to physicians by spending $121.6 million on sales reps for the coming year. The Sacklers paid themselves $335 million that year.

The lawsuit claims that Sackler family members directed efforts to boost sales. An attorney for the family and other board directors is challenging the authority to make that claim in Massachusetts. A motion on jurisdiction in the case hasn’t been heard. That attorney hasn’t responded to a request for comment on the most recent allegations.

Purdue Pharma, in a statement, said the complaint filed by Healey is “part of a continuing effort to single out Purdue, blame it for the entire opioid crisis, and try the case in the court of public opinion rather than the justice system.”

Purdue went on to charge Healey with attempting to “vilify” Purdue in a complaint “riddled with demonstrably inaccurate allegations.” Purdue said it has more than 65 initiatives aimed at reducing the misuse of prescription opioids. The company says Healey fails to acknowledge that most opioid overdose deaths are currently the result of fentanyl.

Purdue fought the release of many sections of the 274-page complaint. Attorneys for the company said at a hearing on Jan. 25 that they had agreed to release much more information in Massachusetts than has been cleared by a judge overseeing hundreds of cases consolidated in Ohio. Purdue filed both state and federal appeals this week to block release of the compensation figures and other information about Purdue’s plan to expand into drugs to treat opioid addiction.

The attorney general’s complaint says that in a ploy to distance themselves from the emerging statistics and studies that showed OxyContin’s addictive characteristics, the Sacklers approved public marketing plans that labeled people hurt by opioids as “junkies” and “criminals.”

Richard Sackler allegedly wrote that Purdue should “hammer” them in every way possible.

While Purdue Pharma publicly denied its opioids were addictive, internally company officials were acknowledging it and devising a plan to profit off them even more, the complaint states.

Kathe Sackler, a board member, pitched “Project Tango,” a secret plan to grow Purdue beyond providing painkillers by also providing a drug, Suboxone, to treat those addicted.

“Addictive opioids and opioid addiction are ‘naturally linked,'” she allegedly wrote in September 2014.

According to the lawsuit, Purdue staff wrote: “It is an attractive market. Large unmet need for vulnerable, underserved and stigmatized patient population suffering from substance abuse, dependence and addiction.”

They predicted that 40-60 percent of the patients buying Suboxone for the first time would relapse and have to take it again, which meant more revenue.

Purdue never went through with it, but Attorney General Healey contends that this and other internal documents show the family’s greed and disregard for the welfare of patients.

This story is part of a reporting partnership between WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

A version of this story first ran on WBUR’s CommonHealth. You can follow @mbebinger on Twitter.

Victoria Knight: The more opioid marketing, the more overdose deaths

By VICTORIA KNIGHT

Researchers sketched a vivid line on Jan. 18 linking the dollars spent by drugmakers to woo doctors around the country to a vast opioid epidemic that has led to tens of thousands of deaths.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, looked at county-specific federal data and found that the more opioid-related marketing dollars were spent in a county, the higher the rates of doctors who prescribed those drugs and, ultimately, the more overdose deaths occurred in that county.

For each three additional payments made to physicians per 100,000 people in a county, opioid overdose deaths were up 18 percent, according to the study. The researchers said their findings suggest that “amid a national opioid overdose crisis, reexamining the influence of the pharmaceutical industry may be warranted.”

And the researchers noted that marketing could be subtle or low-key. The most common type: meals provided to doctors.

Dr. Scott Hadland, the study’s lead author and an addiction specialist at Boston Medical Center’s Grayken Center for Addiction, has conducted previous studies connecting opioid marketing and opioid prescribing habits.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to link opioid marketing to a potential increase in prescription opioid overdose deaths, and how this looks different across counties and areas of the country,” said Hadland, who is also a pediatrician.

Nearly 48,000 people died of opioid overdoses in 2017, about 68 percent of the total overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2000, the rate of fatal overdoses involving opioids has increased 200 percent. The study notes that opioid prescribing has declined since 2010, but it is still three times higher than in 1999.

The researchers linked three data sets: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database that shows drugmakers’ payments to doctors; a database from the CDC that shows opioid prescribing rates; and another CDC set that provides mortality numbers from opioid overdoses.

They found that drugmakers spent nearly $40 million from Aug. 1, 2013, until the end of 2015 on marketing to 67,500 doctors across the country.

Opioid marketing to doctors can take various forms, although the study found that the widespread practice of providing meals for physicians might have the greatest influence. According to Hadland, prior research shows that meals make up nine of the 10 opioid-related marketing payments to doctors in the study.

“When you have one extra meal here or there, it doesn’t seem like a lot,” he said. “But when you apply this to all the doctors in this country, that could add up to more people being prescribed opioids, and ultimately more people dying.”

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, said these meals may happen at conferences or industry-sponsored symposiums.

“There are also doctors who take money to do little small-dinner talks, which are in theory, supposed to educate colleagues about medications over dinner,” said Kolodny, who was not involved in the study. “In reality this means doctors are getting paid to show up at a fancy dinner with their wives or husbands, and it’s a way to incentivize prescribing.”

And those meals may add up.

“Counties where doctors receive more low-value payments is where you see the greatest increases in overdose rates,” said Magdalena Cerdá, a study co-author and director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at the New York University School of Medicine. The amount of the payments “doesn’t seem to matter so much,” she said, “but rather the opioid manufacturer’s frequent interactions with physicians.”

Dr. , who is the co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness and was not affiliated with the study, said that the findings about the influence of meals aligns with social science research.

“Studies have found that it may not be the value of the promotional expenditures that matters, but rather that they took place at all,” he said. “Another way to put it, is giving someone a pen and pad of paper may be as effective as paying for dinner at a steakhouse.”

The study says lawmakers should consider limits on drugmakers’ marketing “as part of a robust, evidence-based response to the opioid overdose epidemic.” But they also point out that efforts to put a high-dollar cap on marketing might not be effective since meals are relatively cheap.

In 2018, the New Jersey attorney general implemented a rule limiting contracts and payments between physicians and pharmaceutical companies to $10,000 per year.

The California Senate also passed similar legislation in 2017, but the bill was eventually stripped of the health care language.

The extent to which opioid marketing by pharmaceutical companies fueled the national opioid epidemic is at the center of more than 1,500 civil lawsuitsaround the country. The cases have mostly been brought by local and state governments. U.S. District Judge Dan Polster, who is overseeing hundreds of the cases, has scheduled the first trials for March.

In 2018, Kaiser Health News published a cache of Purdue Pharma’s marketing documents that displayed how the company marketed OxyContin to doctors beginning in 1995. Purdue Pharma announced it would stop marketing OxyContin last February.

Priscilla VanderVeer, a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, said that doctors treating patients with opioids need education about benefits and risks. She added that it is “critically important that health care providers have the appropriate training to offer safer and more effective pain management.”

Cerdá said it is also important to consider that the study is not saying doctors change their prescribing practices intentionally.

“Our results suggest that this finding is subtle, and might not be recognizable to doctors that they’re actually changing their behavior,” said Cerdá. “It could be more of a subconscious thing after increased exposure to opioid marketing.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Victoria Knight: vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

Purdue Pharma played down OxyContin addiction danger

Side-effects of oxycodone, the generic name for OxyContin, the brand name of a controversial Purdue Pharma product.

By FRED SCHULTE

Two decades ago, Purdue Pharma, based in Stamford, Conn. {see headquarters below}, produced thousands of brochures and videos that urged patients with chronic pain to ask their physicians for opioids such as OxyContin, arguing that concerns over addiction and other dangers from the drugs were overblown, company records reveal.

Kaiser Health News earlier this year posted a cache of Purdue marketing documents that show how the pharmaceutical company sought to boost sales of the prescription painkiller, starting in the mid-1990s.

Purdue turned the records over to the Florida attorney general’s office in 2002 during its investigation of the company. Additional Purdue documents from the Florida investigation detail how the company targeted patients and allayed addiction worries.

“Fear should not stand in the way of relief of your pain,” a pivotal marketing brochure said.

Purdue said it handed out thousands of copies of the brochure, which emphasized consumer power in treating pain, as well as a videotape. “The single most important thing for you to remember is that you are the authority on your pain. Nobody else feels it for you so nobody else can describe how much it hurts, or when it feels better,” the pamphlet states.

More than 1,500 pending civil lawsuits, filed mostly by state and local governments, allege that deceptive marketing claims helped fuel a national epidemic of opioid addiction and thousands of overdose deaths.

Last week, the New York attorney general’s office filed another suit that accuses Purdue of operating a “public nuisance” in it sales tactics and marketing of opioids. Like many others, the suit demands compensation for addiction treatment costs and other problems. Purdue and other drugmakers have denied all allegations.

President Trump said last Thursday he wants the federal government to sue drugmakers in response to the addiction epidemic.

The Purdue brochure from the late 1990s spurred recent criticism from drug safety experts. Dr. G. Caleb Alexander, a physician at the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said the sales pitch was “simply not true” and called it “a smoking gun.”

“We have learned the hard way that many patients develop opioid [addiction] when using these medicines as prescribed,” he said.

Alexander said other drugmakers also appealed to patients hoping to influence their doctors — a tactic that was relatively new in the late 1990s. But Alexander said he was “shocked” to hear that Purdue did so with OxyContin, given the risks posed by long-term use of the morphine-like narcotic.

“These drugs [opioids] are in a class of their own when it comes to the harms that they have caused,” Alexander said.

The internal Purdue documents, dating from 1996 to 2002, show that the company began marketing OxyContin to doctors in late 1995 for treating moderate to severe cancer pain. With modest sales of $49.4 million in 1996, Purdue posted a loss of $452,000 on the drug. In 1997, sales reached $146.5 million for a pretax profit of $16.5 million, the company records show.

In 1998, as Purdue hawked OxyContin for conditions such as arthritis and back pain, it decided to “increase communications” with patients, company records show.

The goal: “convince patients and their families to actively pursue effective pain treatment. The importance of the patient assessing their own pain and communicating the status to the health care giver will be stressed.”

Purdue’s six-page pamphlet for patients, provided to the Florida attorney general, was titled “OxyContin: A Guide to Your New Pain Medicine.” “Your health care team is there to help, but they need your help, too,” the pamphlet says. It says OxyContin is for treating “pain like yours that is moderate to severe and lasting for more than a few days.”

To patients or family members worried about addiction, Purdue’s pamphlet said: “Drug addiction means using a drug to get ‘high’ rather than to relieve pain. You are taking opioid pain medication for medical purposes. The medical purposes are clear and the effects are beneficial, not harmful.”

Asked to comment this week, Purdue spokesman Robert Josephson said the company “discontinued the use of this piece many years ago.”

Dr. Michael Barnett, a physician and assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said that some of Purdue’s early marketing claims may have seemed reasonable to many doctors 20 years ago.

But he faulted the medical profession for not demanding scientific evidence that opioids were in fact safe and prudent for widespread use.

“I think a lot of physicians are coming to the realization that a lot of what we were taught about pain management was pure conjecture,” he said. “I feel foolish for believing it.”

In hindsight, he said, Purdue’s sales tactics seem “almost a satire of an unscrupulous corporation that really has no interest in understanding the implications and complications of people using their drugs.”

Dr. Art Van Zee, a physician in southwestern Virginia who was among the first to recognize the ravages of OxyContin misuse, said that some people who became addicted were already drug abusers.

But he added: “There clearly are people that I’ve taken care of who took it as directed orally and became opioid-addicted.”

Purdue also paid a New York City production company to shoot a videotape called “From One Pain Patient to Another,” featuring testimonials by seven patients from the Raleigh, N.C., area under the care of pain doctor Alan Spanos. Filming took place at the patients’ homes, places of work and other area locations on July 17, 1997, according to the documents.

Purdue did not pay the patients, though Spanos received $3,400 as a “physician spokesman” on that video and another, the company records state. Contacted recently by phone, Spanos would not comment. In the documents, Purdue said that the patients “participated willingly, wishing to speak out regarding the importance to them of being able to receive effective therapy for their chronic pain.”

Between January 1998 and June 2001, Purdue distributed 16,000 copies of the video to doctors, who showed them to selected patients.

The video did not mention OxyContin directly, but the Food and Drug Administration did balk at a claim in the video that fewer than 1 percent of people taking opioids became addicted. The FDA said that claim was not substantiated, according to a December 2003 General Accountability Office audit.

Purdue destroyed remaining copies of the video in July 2001, including 4,434 Spanish-language versions, according to the company records.

By then, annual OxyContin sales had topped $1 billion as Purdue pushed to “attach an emotional aspect to non-cancer pain so physicians treat it more seriously and aggressively,” according to the company’s marketing reports.

Asked about the video, Purdue spokesman Josephson said the drugmaker has not made that claim — regarding 1 percent addiction — “in more than 15 years.”

Purdue submitted the marketing records to the Florida attorney general’s office during its investigation of the company. The state settled the case in 2002 when Purdue agreed to pay $2 million to help set up an electronic prescription-tracking program.

Florida officials released the records to two Florida newspapers in 2003 after Purdue lost a court battle to keep them confidential. KHN posted some of those documents earlier this year for readers to review on its website.

Purdue's headquarters is in this building in downtown Stamford.

David Warsh: The sleazy Sacklers' lethal painkiller promotions and the need for a 'Health Fed'

President Trump has declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, rather than a national emergency, since the Federal Emergency Management Agency is over-extended in dealing with storm relief. Unfortunately, the Hospital Preparedness and Public Health Emergency Funds are equally strapped for cash, running respectively at 50 percent and 30 percent below their peak levels of a decade ago. Congress will have to act.

It was, therefore, an especially good time for “The Family that Built an Empire of Pain,” to appear last week in The New Yorker. You can read Patrick Radden Keefe’s remarkable story about the wellsprings of the crisis for free online, more easily, if less pleasurably, than in the magazine itself. The sub-head states, “The Sackler dynasty’s ruthless marketing of painkillers has generated billions of dollars – and millions of addicts.”

Others have worked on the Sackler family story over the years, documenting its leading role in producing the opioid epidemic, including Barry Meier, of The New York Times, who first uncovered the extensive marketing efforts for OxyContin, and the Los Angeles Times team that documented the "12-Hour Problem '' that Keefe describes. But none has achieved anything like the rhetorical force of Keefe’s article. Once it is reworked as a book, I expect that “Empire of Pain” will eventually attain the status of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and other classics of social criticism. It is an astonishing story. You might as well read it now.

The three brothers of the Sackler family — Arthur (1913-87), Mortimer (1916-2010), and Raymond (1920-2017) – are far better known as philanthropists than as pharmaceutical entrepreneurs. All three attended medical school and subsequently worked together at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, in Queens, N.Y. Arthur put himself through medical school working for William Douglas McAdams, a small advertising agency specializing in medical markets, then bought the business. In 1952, the three physicians bought Purdue Frederick, a little manufacturer of patent medicines in Greenwich Village (and no relation to the famous university). Each owned a third.

While Mortimer and Raymond built the company, Arthur took a more distant role, concentrating on medicine as editor in chief of the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Psychopathology from 1950-1962. In 1960, he founded a biweekly newspaper, Medical Tribune, which eventually reached 600,000 subscribers.

The Sackler family grew tolerably rich on the sale of Valium, which between 1969 and 1982 was the top-selling pharmaceutical drug in the United States. When Sen. Estes Kefauver (D.-Tenn.) investigated the rapidly growing pharmaceutical industry in the early 1960s, a staff member prepared a memo that read, in part,

"The Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation in that it can devise a new drug in its drug development enterprise, have the drug clinically tested and secure favorable reports on the drug from various hospitals with which they have connections, conceive the advertising approach and prepare the actual advertising copy with which to promote the drug, have the clinical articles as well as the advertising copy published in their own medical journals, [and] prepare and plant articles in newspapers and magazines.''

Enter Raymond’s son Richard Sackler (b. 1945), in 1971, fresh out of medical school. Starting as assistant to his father, during the next 30 years he presided over efforts to develop OxyContin and turn it into the best-selling pain medicine in the world. How the company, re-named Purdue Pharma, managed that forms the bulk of Keefe’s 13,000-word account.

Simply put, thanks to massive marketing efforts, the long-lasting narcotic came to be widely prescribed, not just for severe pain associated with surgery or cancer, but for almost any discomfort, including arthritis, back pain and sports injuries – despite its obviously addictive properties. Early versions turned out to be ruinously easy to abuse; later editions turned out to be a gateway to the use of cheaper heroin. More than 300,000 lives have been lost to overdoses of opioid drugs since 2000; perhaps 10 times as many have been shattered.

Arthur’s heirs sold their father’s share of the company to his brothers sometime after 1987. Mortimer moved to Europe to spend and save his dividends Raymond ran the company day-to day for many years, and died only last July. Nine family members are among the directors of the private company. Past president Richard Sackler was deposed last year, as part of Kentucky’s complaint that many of Purdue’s marketing methods were illegal. A battle to unseal his testimony has ensued. Many more lawsuits are in train; their tactics resemble the campaign to rein in the use of tobacco. Congress can be expected to again hold hearings.

The editorial board of The Wall Street Journal also addressed the topic, uncharacteristically ignoring the supply side in favor of demand factors, in a piece headlined "The Opioid Puzzle'' (subscription required). The editorial board’s interest was piqued by “the government’s role is allowing too-easy access to painkillers, particularly among society’s poor and vulnerable.”

Medicaid recipients receive prescriptions for twice as much pain medication as those not covered by the government’s low-income plan, the editors wrote, citing government figures. And one out of every three Medicare beneficiaries received opioid prescriptions last year, half a million of them in extravagant doses. “The only way to explain this cascade of pills is an epidemic of fraud,” the editors concluded.

Better to put the two analyses together. OxyContin sales are estimated to have been around $35 billion over the last 20 years. An enormous portion of that was surely paid by the government as insurance subsidies. Only when you see the two programs unfolding together do you begin to comprehend the nature of the problem – the entrepreneurial genius of the Sackler family on the one hand, developing and marketing popular mood-altering and painkilling drugs since the 1950s; on the other, the rise of government medical insurance since 1966, when the Medicare program went into effect.

Throw in the mostly unrecognized extent to which big pharmaceutical manufacturers have discouraged all manner of research on the painkilling applications of medical marijuana, and you have a real witches’ brew.

The U.S . health-care industry may be, in certain respects, the best in the world; certainly it is the most expensive. As the opioid epidemic demonstrates, it offers a colossal field for mischief. The editorial board of the WSJ is right about this much: innovation is the answer, to the opioid crisis, and much else among the medical sector’s many other ills. In this case the desideratum is regulation – not Pentagon-style hierarchy, but rather the decentralized and consensual decision-making represented by the Federal Reserve System.

The blueprint developed 10 years ago by former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle (D.-South Dakota) in his run-up to a presidential campaign that was ultimately overtaken by that of the junior senator from Illinois, Barack Obama, is still the only model that make sense. Daschle imagined a dozen or so regional health-care authorities, sharing power among regulators, physicians, hospitals, insurers, device and pharmaceutical providers, governed by a federal board of governors insulated as much as possible from politics.

A Health Care Fed eventually will deliver efficiency – and diminish freebooting – in the enormous sector, in much the same way the Federal Reserve Board stabilized the similarly turbulent banking industry a hundred years ago. It’s just going to take more time – another generation or two, I would guess.

David Warsh, a long time financial columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economic principals. com, where this first appeared.

The Sacklers' deadly drug peddling

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal2.com

The Sackler drug-fortune family, whose total wealth is estimated at around $15 billion, recalls the over-the-top Balzac line that “behind every great fortune is a great crime.’’ Theirs was to help create the opioid epidemic.

The Sacklers are the status-obsessed clan that puts its name in large letters on bronze and other fancy signs announcing members’ gifts to already rich museums and colleges and universities (including New England Ivy League schools) to affirm their membership in the social/mercantile aristocracy. Most of their money comes from their closely held company Purdue Pharma, which hugely hyped their painkiller OyxContin to physicians and patients. Purdue lied that the opiate was remarkably safe. No. It's a menace.

The company’s outrageous marketing of OxyContin has led to massive addiction and the overdose deaths of many thousands of people.

Even before OxyContin, Arthur Sackler, one of the three brothers who bought then tiny Purdue Pharma in 1952 and then built it up in a vastly profitable behemoth, heavily and misleadingly promoted the glories of the benzodiazepine Valium when he was an ad man. Valium is also very addictive and potentially lethally dangerous. What an innovative family!

From the start, the family-held firm’s secrets to success have included (as with some members of Big Pharma) its relentless pushing of its products to physicians, with junkets to fancy places, paying doctors big fees to give very short speeches and other perks that some might simply call bribes in the world’s most avaricious health “system.’’

Instead of showing off its money with well-advertised contributions to institutions catering to the elite, the Sacklers would do far better to set up a nonprofit chain of drug-rehabilitation clinics to address the vast damage that they have done.

In a weird way, New Englanders have seen this sort of money-laundering before, when the “China Trade’’ of the late 18th and early 19th centuries earned fortunes from opium sales. Some of it ended up in (what are now called) Ivy League colleges and other prestigious institutions. Opiates forever!