Chris Powell: Sanctimony city and state milk grim history for patronage

A 1743 copy of the Treaty of Hartford of 1638, which sought to eradicate the Pequot cultural identity by prohibiting the Pequots from returning to their lands, speaking their tribal language, or referring to themselves as Pequots.

The nave of Trinity Church, on the New Haven Green. The Gothic Revival building was constructed in 1814-1816.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Two more tedious but true tales from the Sanctimony City and the Sanctimony State have unfolded.

In New Haven dozens of people gathered at Trinity Church on the city's green on March 8 to mark the 200th anniversary of the last recorded sale of slaves in the city and Connecticut -- two women who were paraded to the green and purchased by an abolitionist who eventually set them free. Last week's gathering called itself a “service of lamentation and healing."

Meanwhile, at the state Capitol, a legislative committee considered a resolution to condemn the Treaty of Hartford of 1638, which marked the end of the war between the Pequot Indian tribe and its adversaries -- the English, Mohegan and Narragansett tribes. The war killed most of the Pequots and the treaty sought to nullify the few who were left, bestowing them on their adversaries as slaves and prohibiting the tribe's reconstitution.

The events implied that modern society bears some enduring guilt for the abominations of centuries past. Indeed, establishing this guilt seems to have been the political objective. This was mistaken and ironic.

Americans like to believe in their country's exceptionalism, but slavery was and remains a worldwide phenomenon going back millennia and transcending nations and races. The slaves brought to the United States and delivered to white masters had been sold first in west Africa by other Black people. To some extent slavery continues today in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

So in the larger context Connecticut's connection to slavery may be more remarkable for the efforts to overthrow it than to sustain it. In any case in no country was there a more devastating war to destroy slavery than what happened in the United States.

But even as New Haveners gathered to “lament" and “heal" from the wrongs of two centuries ago, the city remained the scene of a devastating wrong for which no sanctimonious services of lamentation and healing are ever held. That is, most of the city's children -- members of racial and ethnic minorities, far more numerous than there were ever slaves in the state -- lack parents, live in poverty, and fail in school.

New Haven's schools have the worst chronic absenteeism in the state and many of those schools are in terrible repair. Many of their students, undereducated and demoralized, graduate to a more subtle but far more prevalent form of slavery.

As for the Indian wars of almost four centuries ago, they were full of atrocities, though today it is politically correct to remember only those of the winning side.

The massacre of the Pequots in May 1637 in what is now Groton was the most horrible thing ever to happen in Connecticut. But the Pequots started the war. The tribe's very name meant “destroyers" and they already had made deadly enemies of the Mohegans and Narragansetts long before attacking the English settlement in Wethersfield in April 1637, killing nine unarmed people, including three women, kidnapping two women, and killing the settlement's cattle.

So a month later the English, Mohegans and Narragansetts united in a conclusive slaughter.

While the Treaty of Hartford fairly can be called genocidal, it was itself a response to genocide in an era when genocide was common.

No morality is taught by the sanctimony that evoked these horrors last week. Slavery has had no constituency in Connecticut since those last slaves were sold in 1825. Nor is there any constituency here for genocide, though in modern war civilians are often killed.

But there is a selfish political constituency for mobilizing the horrors of the past.

Sanctimoniously reminding people of slavery can intimidate them out of opposing the claims of racial minorities for more government patronage, though that patronage isn't righting any wrongs.

And sanctimoniously reminding people of the Treaty of Hartford may insulate the absurd patronage enshrined in state law whereby the ultra-distant descendants of the ancient Pequots, the victims of genocide, share a casino duopoly with the ultra-distant descendants of the ancient Mohegans, that genocide's co-perpetrators.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Chris Powell: Native Americans could be pretty nasty, too

A man displaying himself as a Pequot warrior at the Pequot Museum at the Foxwoods casino in Connecticut

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Replacing Columbus Day with "Indigenous Peoples Day" on its school calendar, Manchester's Board of Education has concluded that the Italian navigator sailing for Spain should not be considered such a hero after all, since, in discovering the New World, he began the colonial subjugation of its natives.

This is fair criticism, and people are always free to change their minds about who should be honored with holidays, statues, and such. But the school board does not seem to have explained why "indigenous peoples" are any more deserving of special honor than Columbus himself. After all, these days nearly everyone in the United States is "indigenous," and back in Columbus' time and throughout the colonial era in the Western Hemisphere "indigenous" people weren't the noble savages of romantic myth but carried the same character and cultural flaws as the rest of humanity.

The "indigenous peoples" of old warred against each other as much as the European settlers warred against them. They even made alliances with the Europeans against other aborginals. Though it does not seem to be taught in many schools in Connecticut, this is precisely the state's own story. Indian tribes living here invited the Europeans in Massachusetts to settle among them as allies against the Pequots, an aggressive tribe that had moved into the area and was preying on the other tribes and whose very name is said to have meant "destroyers."

Before long the Pequots were destroyed themselves, nearly all of them exterminated, including noncombatant women and children, in what was essentially genocide committed by the warriors of an alliance of the Europeans and the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes.

Of course tribal wars go back through the Bible to the beginning of human history. There have always been aggressors and victims, and being "indigenous" never automatically conveyed virtue any more than it does today. So while there is a case for demoting Columbus and leaving his day unmarked, the only purpose of putting "indigenous peoples" in his place on the calendar is to advance the politically correct proposition that all of American history has been dishonorable and thereby to induce guilt to intimidate the public in the face of the PC agenda generally.

This political correctness contaminates public education throughout the county and now, with Indigenous Peoples Day, reigns in Manchester's schools as well as Bridgeport's, New London's, and West Hartford's.

But despite its many ugly aspects, American history on the whole exemplifies what used to be called the Ascent of Man, the gradual but steady extension of liberty and democracy and the improvement of living standards. The sacrifices made in pursuit of these objectives are profound though not always well-taught.

There is another reason Manchester's school board has not just erased Columbus Day from its calendar but declared it a different holiday to honor a whole class of people good and bad. That is, Columbus Day remains by law a state holiday for which government employees must be paid without working.

The board can call this paid day off whatever it wants, but until the General Assembly and the governor erase him, Connecticut is still honoring Columbus, and politically incorrect as he may have become, crossing the government employee unions is considered worse than politically incorrect -- politically fatal.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn,

Chris Powell: Income-tax fantasies; a colonial-era hero or mass murderer?

Connecticut Republican gubernatorial candidate Bob Stefanowski’s objective of eliminating the state income tax is ridiculous but not for the reason commonly offered -- that the tax produces half state government’s revenue and cutting spending that much never would be practical, not even over the eight years of Stefanowski’s "plan."

Instead Stefanowski’s "plan" is ridiculous because the Democrats probably will retain the state House of Representatives in the coming election and well might recover a clear majority in the Senate, now tied at 18. Any budget will require the General Assembly’s approval and no house controlled by Democrats will ever agree to even modest spending cuts.

A Democratic majority in just one house would let Stefanowski off the hook -- along with Republican legislators, who may be glad if they stay in the minority and thus avoid responsibility for closing next year’s projected state budget deficit of more than $4 billion.

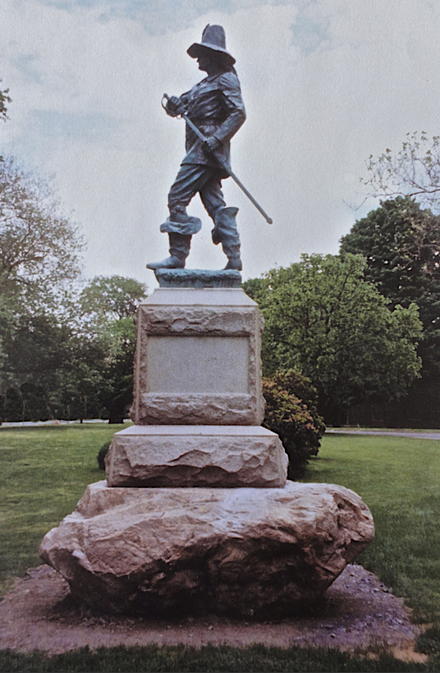

Statue of Captain John Mason in Windsor, Conn. Below, the plaque with it.

— Photo by MoonWaterMan

Students from Central Connecticut State University visited a park in Windsor the other day to contemplate the statue of a hometown hero of sorts, Captain John Mason, a founder of the Connecticut colony and leader of what might be called the European tribe in the Pequot War in 1637. Mason was in command when most of the Pequots, including women and children, were slaughtered by gunshot and fire in their fort in Groton, a genocide celebrated then but not so much now.

Two decades ago Mason’s statue was moved from Groton to Windsor to end celebration of the massacre and diminish its memory.

How far political revisionism should go with monuments is always a fair question. Leaders of the late Southern Confederacy are increasingly out of favor, but even George Washington owned slaves and fought in a war against Indian tribes. For the time being, Washington’s sins remain forgiven, overtaken by his immense service to his country.

So what is to be done with Mason? Whether his statue stays or goes somewhere else, like a museum, it is important to put him in the context of his time. Standards were primitive four centuries ago -- not just for the European colonists, who generally regarded the aboriginals as savages, but also for the Indians. Everyone was tribal.

Indeed, Europeans living in Massachusetts were actually invited to settle in Connecticut because of Indian tribal rivalry and war here. The Pequots, whose name meant "destroyers," were not native to the area, having come from what is now upstate New York, and they preyed on less combative tribes who imagined the Europeans as allies. Such an alliance between the Europeans and the Mohegan tribe indeed exterminated the Pequots. While today the two tribes, reconstituted, are partners in the casino business, back then they were as cutthroat to each other as the Europeans and the Pequots were to each other.

Connecticut has plenty of history to celebrate and less to regret than some states. But Mason would not have a statue except for the massacre of the Pequots. The statue’s placement in the park in Windsor implies that he is still officially regarded as a hero. Since Mason is buried in a cemetery in Norwich, a city he helped found, his statue might better be moved to his grave, where people could regard it without any official suggestion of heroism.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn.