Llewellyn King: A soldier of fortune’s plan to hook up Puerto Rico and beyond

Adam Rousselle

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Some men go to war and come back broken. Others come back and black out that experience. Some are never whole again.

But some leave active duty inspired to help, to change things they can for the better. Adam Rousselle is such a man.

Rousselle saw service fighting with the Contras in Honduras and later was on active duty in Iraq, fighting in Operation Desert Storm. He left the U.S. Army with a disability, having ascended from private to officer, and set out to be an entrepreneur. His aim was to do good as well as provide a life for himself and his young bride.

Returning to Honduras, he founded a mahogany-exporting company. It was a smashing success until he ran afoul of the government and shady operators.

Suddenly, Rousselle was accused of taking mahogany trees illegally, although he said he was scrupulous in cutting only trees identified for removal by the Honduran government.

His staff and his father were imprisoned. His father died in prison — an open-air enclosure without shelter. But Rousselle still had to get his staff released and his name cleared.

His solution: Identify and inventory the trees in the Honduran rainforest. Call in science, can-do thinking and a new satellite application.

Working with NASA images from space, Rousselle was able to put every mahogany tree into a database and to identify the maturity and health of each tree through the signature of the crown. Millions of trees were identified, and Rousselle was able to prove that the trees he was supposed to have cut illegally were alive and well in the rainforest.

Rousselle was exonerated and his staff was freed, after three and a half years in detention, with help from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). With the new science of tree identification, Rousselle helped Boise Cascade Co. to inventory its entire timberland holdings, and electric utilities have been able to identify and remove dead trees in high wildfire-risk areas.

Another of Rousselle’s innovations was an energy-storage system, using abandoned quarries as micropump storage sites. “These are all over every country, close to the highest energy demand centers,” Rousselle said. He got many of these permitted and others are being examined.

As I write, a quarter of Puerto Rico’s 3.22 million people are without electricity after Hurricane Ernesto swept through their island. Ernesto has left slightly less damage than Hurricane Maria in 2017. In that hurricane, more than a third of the island was plunged into darkness and some communities were without power for nine months.

For several years, Rousselle has been working on a plan to help Puerto Rico by supplying electricity via cable from the U.S. mainland.

It is a grand engineering project that would, Rousselle said, cut the cost of electricity on the island in half and ensure hurricane-proof supply. While it wouldn’t deal with the problem of the Puerto Rican grid’s fragility, it would solve the generation problem on the island, which is outdated and based on imported diesel and coal, both very polluting. Also, it would help solve the bulk transmission problem.

The Biden administration and a swathe of the U.S. energy establishment would like to replace that electricity generation with renewables, such as wind and solar.

But Rousselle pointed out that on-island wind and solar would both be highly vulnerable in future hurricanes. Green electricity is well and good, but generated securely on the U.S. mainland is best, Rousselle said.

He said that his 1,850-mile, undersea cable project would deliver 2,000 megawatts of electricity from a substation in South Carolina to a substation in Puerto Rico. That would leave the Puerto Rico electric supply system free to concentrate on upgrading the fragile island grid.

Worldwide, there is a lot of activity in undersea electricity transmission. All are aimed at bringing renewable electricity from where there is an abundant wind and solar resource to where it is needed. The two most ambitious plans: One to link Australia and Singapore (2,610 miles) and another to link Morocco to the United Kingdom (2,360 miles). There is also a plan to hookup Greece, Cyprus and Israel via undersea cable.

The longest cable of this type (447 miles) went into operation last year, bringing Danish wind power to the UK.

One way or another, undersea electricity transmission is here and it is the future.

After Puerto Rico, Rousselle, ever the soldier of fortune, hopes to hook up the entire Caribbean Basin in an undersea grid, moving green energy out of the reach of tropical storms.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Longing for an outbreak of American civility

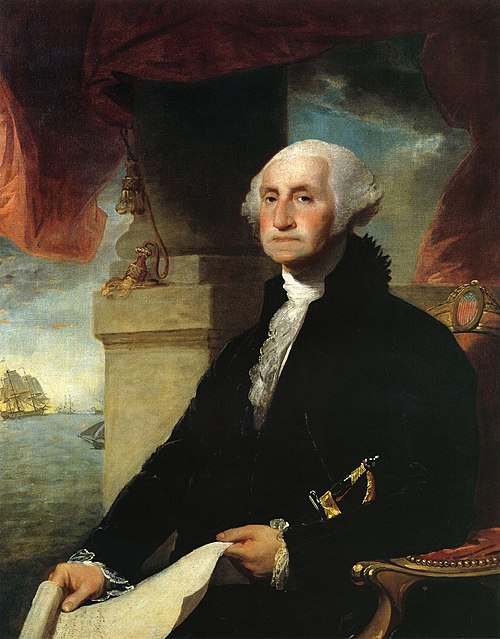

George Washington published a book called Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour In Company and Conversation.

Little things mean a lot and manners mean a great deal. Fifty years after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, our national manners about race seems to be fraying.

After King was fatally shot, I was in the thick of the riots in Washington. The one thing I recall with great clarity is — even as shops were being looted and fires set — the rioters paused to be polite to me. Several times men, who were out to destroy or steal as much as they could, ushered me to safety and inquired if I was all right.

In those race riots, there were outbreaks of manners; of people seeing each other as people. Richard Harwood of The Washington Post noticed the same outbreak of politeness and wrote about it.

That is why it is distressing to see socially considerate language deteriorate. It means a deterioration in manners.

In these 50 years, we have come both a long way and not far enough. How we talk about things does matter.

Twenty years ago, while I was hanging out with some Irish television journalists in a bar in Dublin, they began attacking a local newscaster. Nothing unusual there: The writers and producers who write the words spoken on air often resent the newscasters who read them.

They are invariably paid much more than the people who prepare the broadcasts, reap the rewards of celebrity and can be a pain. Remember Ted Baxter in “The Mary Tyler Moore Show”?

In a final comment, one of the most senior of the journalists declared, “Let’s face it, he’s just a Protestant prick!” This remark gave me a start and made me glad that I was naturalized American. We might call someone names in America, but we would not drag in religious affiliation.

In Washington, at the venerable National Press Club, another little shocker. A Malaysian publisher, discussing the dominant position of the Chinese minority in his country, said in a voice so loud that other guests looked around, “The only straight thing about a Chinaman is his hair.” We would neither say nor think that.

A small thing, words and the related manners they codify, but they set the tone. We scatter the words and they grow into attitude and policy.

In my own negotiations — business negotiations, labor negotiations and news-story negotiations — manners have been an essential part of them. If you have publicly denigrated your opponent before you sit down, you will have traded a position on the high ground for one in the swamp.

So why is President Trump, who fancies himself the deal-maker in chief, the denigrator in chief? Dissing others is like lying; no one will believe anything that comes out of your mouth later. A veracity gap has a permanence about it.

The Bad, Sad News from Puerto Rico

I have had a lifelong interest in electricity. As a kid in Africa, I learned the difference between having it and not. It is the difference between living and subsisting, hope and hopelessness.

I read an alarming story in The Intercept, an online news publication, which says that despite more than 1,500 highly experienced emergency workers from the mainland in Puerto Rico, crews are sitting idle while the supplies, which would enable them to get on with the job of restoring power to about 1 million American citizens, are locked away in warehouses.

Yankee can-do is apparently not doing, owing to local incompetence and maybe corruption.

The Debate over Embassies: Don’t Lose Track of the Facts

Amid all the outrage and some endorsement of Trump’s moving the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the fact that the two cities are close to each other got lost. It is a distance of 50 miles and I have traveled it several times in, as I remember, about 40 minutes or less by taxi.

As for the new London embassy, it is on the London Underground in Nine Elms, an up-and-coming area in a dynamic and changing city.

It is not Ye Olde London: Just look at the skyline and marvel.

The Things They Say

“It’s not tyranny we desire; it’s just, limited, federal government.” — Alexander Hamilton.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking@gmail.com), host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, is a veteran publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant.

Statehood for Puerto Rico

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

About 80 percent of Holyoke, Mass., public school students are of Puerto Rican background. Now district officials are preparing for a flood of new students as a result of the ravages of hurricanes Irma and, especially, Maria, in that U.S. commonwealth. Other urban school districts in southern New England, especially in Massachusetts and Connecticut, that have lots of Puerto Ricans, are making similar arrangements.

What will immediately help the ravaged island is suspension of the Jones Act, which requires goods shipped between American ports to only be carried on ships built primarily in the United States and with U.S. citizens as their owners and crews. Happily, President Trump last week suspended the law. But it may be time to get rid of it for good.

The idea behind this 1920 law was to protect the American shipping business.

But the Jones Act dramatically raises the prices of goods brought into the island. Puerto Ricans must absorb extra shipping costs of items that could be shipped directly and much more cheaply from a nearby island, such as Hispaniola or Jamaica. The Jones Act forces shippers to route through an American port, in Puerto Rico’s case most likely from Jacksonville and Miami.

Puerto Rico desperately needs supplies to start to recover from these terrible storms.

For the longer term, Daniel W. Drezner, of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts wrote:

“This is not just about recovering from Hurricane Maria. It is also about Puerto Rico’s long-term future. If the Jones Act were suspended, consumer prices would drop by 15 percent to 20 percent and energy costs would plummet. A post-Jones Puerto Rico could modernize its infrastructure and develop its own island-based shipping industry. Indeed, the island could become a shipping hub between South America, the Caribbean and the rest of the world. This industry would generate thousands of jobs and opportunities for skilled laborers and small businesses. On an island with official unemployment over 10 percent (but actually closer to 25 percent), this would energize their entire workforce.’’

Meanwhile, it continues to be perverse that residents of Puerto Rico and the nearby U.S. Virgin Islands, while American citizens who can serve in our armed forces, can’t vote in U.S. elections. But that, of course, goes back to the fact that Puerto Rico is not a state. Out of fairness and for national-security concerns, the island, perhaps combining with the U.S. Virgin Islands, should become one.

If it had been a state, it probably wouldn’t have suffered thelethal delays in receiving aid after the hurricanes. Statehood would mean that Puerto Ricans would have to pay federal taxes but that the respect and assistance that they’d get as full parts of the United States would make that well worth it.