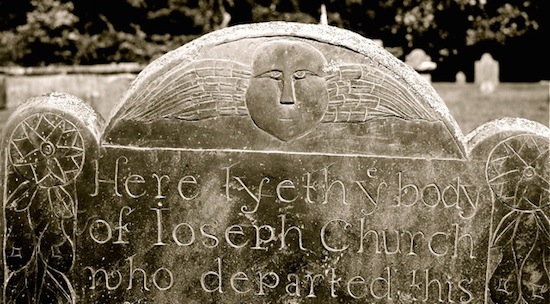

‘From sea’s slime’

The town on Nantucket Island, when it was still called Sherburne, in 1775.

“Here in Nantucket, and cast up the time

When the Lord God formed man from the sea's slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung'd combers lumbered to the kill.’’

— From “The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

The real Puritans

Quaker Mary Dyer led to execution on Boston Common, on June 1, 1660, by an unknown 19th Century artist. The Puritans denounced Quakerism from the start.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Sarah Vowell’s chatty (and sometimes a tad vaudevillian and snarky) and well-researched book The Wordy Shipmates is a remarkable combination of drollery and serious, if popular, historical writing. She gets into the heads of the New England Puritans, some of whom were brilliant, such as John Winthrop, Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, and virtually all of whom were literate and wrote a lot, and analyzes how their actions and beliefs help lay the religious, civic and political foundation of what became the United States. Indeed, as the late Anglo-American journalist Alistair Cooke once observed, “New England invented America.’’

She says in the book that “the most important reason I am concentrating on {Massachusetts Bay Colony leader John} Winthrop and his shipmates in the 1630’s is that the country I live in is haunted by the Puritans’ vision of themselves as God’s chosen people, as a beacon of righteousness that all others are to admire.’’

But in Winthrop’s famous and sometimes misquoted and misunderstood line, the colony would be "as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us,’’ he was warning that its members would be judged for how they lived there. And he never called that city “shining.’’

Her book is a very entertaining place to start to learn about the creation of New England and the myths and facts around it. Then you can go and read the much more scholarly work of such academic historians of the region as Harvard’s brilliant Perry Miller (1905-1963).

My father’s ancestors were Massachusetts Bay Puritans, though some fairly early on became Quakers and then were advised to get out of town fast. My only physical things from 17th Century New England and Olde England are some musty religious tracts, which those characters cranked out in large numbers. Worth little but useful reminders of how far away, and near, those people were.

Interior of the Old Ship Church, built in 1681 as a Puritan meetinghouse in Hingham, Mass. Puritans were Calvinists, so their churches were unadorned and plain. It is the oldest building in continuous ecclesiastical use in the United States and today serves a congregation of Unitarian Universalists, whose theology Puritans would have condemned. But Unitarianism evolved from the Puritans via Congregationalism.

My Cape Cod -- from rural to suburban

The Bourne Bridge, over the Cape Cod Canal, with the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge in the distance.

From Robert Whitcombs's "Digital Diary','' in GoLocal24com

We went down to the Cape the other day to stay with a cousin in a house on a harbor on Buzzards Bay. I thought of how much the Cape had changed since my boyhood, in the ‘50s. Then, much of it was truly rural, with small farms and many cranberry bogs. There were no superhighways. Approaching from Boston’s southeastern suburbs, you’d go down Route 3A, which would become increasingly rustic as you headed south, with farm stands and general stores. The closer we got to the Cape Cod Canal, the more the air smelled like pine, as we entered a state forest.

Then the excitement of crossing the Sagamore Bridge onto an island/peninsula then devoid of big box stores, malls and gated retirement communities and on to my paternal grandparents’ gray-shingled house in the village of West Falmouth, the land of which some of my Quaker ancestors had bought from the Indians in the 1600’s. Then, if there were still time, to the beach, where the water was much cleaner and warmer than in Massachusetts Bay, and where the private bathhouse would get destroyed from time to time in hurricanes, to whichBuzzards Bay is particularly vulnerable.

After that, getting some ice cream from the village’s one and only general store. Then maybe a trip to Woods Hole the next day to see the aquarium of the world-famous Oceanographic Institution there. Woods Hole was where some of my ancestors built boats and partnered in the Pacific Guano Co., where bird excrement from Pacific Islands was processed with fish meal to make what was considered in the 19th Century the best fertilizer. Nowadays, it’s hard to think of Woods Hole as a factory town. Rather, it’s now in effect a college town.

As for West Falmouth, while it’s still almost as pretty as it was 60 years, it’s a ghost town to me since virtually everyone I knew there has died or otherwise gone elsewhere.

Or we occasionally approached the Cape from the west, on Route 6, with its strips of clam shacks, cheap motels and kitschy tourist-oriented gift stores. Ugly, but delightful to young children. Now, of course, you miss the local and often tacky texture on the boring big divided highways. And these highways draw in so much out-of-region traffic that the traffic jams on the two road bridges (there’s also the beautiful railroad bridge) mean driving to the Cape can take considerably longer now than in the ‘50s.

Because of that and because too much of this glacial moraine now looks like exurbia or suburbia, we don’t makemany visits anymore to Olde Cape Cod. Still, the air down there still has a certain luminosity.

Amidst kitsch and the drive to show off, a Quaker aesthetic still survives in the prepster Brigadoon

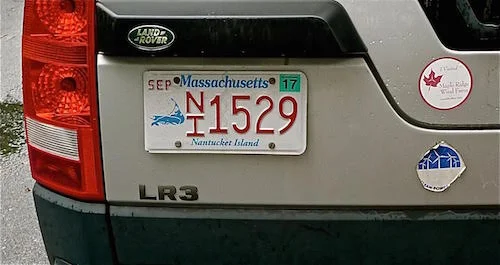

The Nantucket Island license plate appropriately displayed on a Land Rover, a classic off-road SUV for navigating Nantucket's cobblestone streets.

Can the precious island made wealthy by Quaker ship owners and whalers, but now the purview of Ralph Lauren-clad hedge-funders, stand any more cuteness? Would that the hauntingly beautiful island rebel against yet more trite merchandising of this demi-paradise of cedar shingles and windswept moors. Once, the ultimate status symbol was an over-the-sand permit for the bumper of a Jeep, or better yet, an old Land Rover. Now the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has offered another bit of snobbery with a special license plate.

Even so, the new plate is not nearly as exclusive as the various out-of-state vanity plates that are seen on the island. Imagine the pride of the Mr and Mrs Gottrocks, summer residents from somewhere near the horse country of Morristown, N.J., constantly announcing their second domicile on their Audi "Afrika Korps" urban assault vehicle.

Clearly the appeal is for more than the 10,000 or so locals, and anyone across the state can get a Nantucket Island plate for their car. It is a desirable trinket for those who regard the Far Away Land as nirvana – a place of Nantucket baskets, Nantucket red khakis, red brick sidewalks, and more take offs and landings at the airport in the summer than Boston's Logan. $28 of the island plate's $40 fee does go to non-profits that help children, but one wonders if there were not another way to raise charitable contributions than a design that pimps the island's history

Massachusetts paid a Boston brand consulting firm in Boston to glop up a license plate with several fonts. Thank goodness, the identifying NI and numbers are embossed – other states would have offered a tableau of Moby Dick in full-on Nantucket sleigh-ride mode. But no kudos should go to Nantucket artist David Lazarus for his confusing and complicated logo of a sperm whale superimposed on a detailed map of the island.

Such silliness makes a mockery of the centuries-old Quaker aesthetic that gave Nantucket such a strong design identity,as in the house below.

William Morgan is a contributing editor at Design New England magazine and is the author of such books as Yankee Modern and The Abrams Guide to American House Styles.

William Morgan: The Quaker Coast

Photos (below) and commentary by WILLIAM MORGAN

It has been almost a decade since I published a book of photographs on the Cape Cod cottage. Since, then, I have been looking for another suitable topic.

My (more successful) photographer friends tell me no one is underwriting black and white photos taken with film. And my favorite publisher nixed the idea for a photographic study of what I call the Quaker Coast (the towns of Dartmouth and Westport in Massachusetts, and Little Compton, just over the border in Rhode Island), declaring that there would be no market for such a book.

Yet there is something special – and not yet ruined – about those three towns. Fishing and agriculture still survive, if not actually thrive, there. And the mostly unspoiled landscape and the prevalence of a plain vernacular architecture, mostly wrapped in cedar shingles.

In lieu of the fantasy book, I offer the readers of New England Diary three images from the book proposal.

Addendum: Much of Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket were also Quaker. I went to a few family memorial services in the Quaker meeting house in West Falmouth, on the Cape.

Many whalers were of Quaker background -- but that didn't make them gentle at all. Rather, many were tough and rapacious. Many became very successful capitalists whose investments spanned the world.

-- Robert Whitcomb