The wet look

Sunny day flooding in Miami during a “king tide’’.

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 2012.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The stuff below is a heavily edited version of some of the remarks I made in a talk a couple of weeks ago and seem to me particularly resonant as we head into summer coastal vacation season:

Most of us are in denial or oblivious when it comes to sea-level rise caused by global warming. For example, Freddie Mac researchers have found that properties directly exposed to projected sea-level rise have generally gotten no price discount compared to those that aren’t, though that may be changing. And some states don’t require sellers to disclose past coastal floods affecting properties for sale. Politicians often try to block flood-plain designations because they naturally fear that they would depress real-estate values.

So the coast keeps getting more built up, including places that may be underwater in a few decades. It often seems that everyone wants to live along the water.

As the near-certainty of major sea-level rise becomes more integrated into the pricing calculations of the real-estate sector, some people of a certain age can get bargains on property as long as they realize that the property they want to buy might be uninhabitable in 20 years. Younger people, however, should seek higher ground if they want to live near the ocean for a long time.

A tricky thing is that real estate can’t just be abandoned—it must pass from one owner to another. Some local governments’ coastal permits require owners to pay to remove their structures when the average sea level rises to a certain point. Absent such requirements, many local governments’ budgets may not be enough to pay for demolition or the moving costs associated with inundation. There are some interesting liability issues here.

What to do?

Administrative mitigation would include raising federal flood-insurance rates and more frequently updating flood-projection maps. More localities can take stronger steps to ban or sharply limit new structures in flood-prone areas and/or order them removed from those areas. And, as implied above, they should implement flood-experience-and-projection disclosure requirements in sales documents.

As for physical answers to thwarting the worst effects of sea-level rise, especially in urban areas, many experts believe that some form of the Dutch polder approach, which integrates hard stone, concrete or even metal infrastructure, and soft nature-based infrastructure, along with dikes, drainage canals and pumps, may have to be applied in some low places, such as Miami and Boston’s Seaport District. Barrington and Warren, R.I., look like polder country.

Polders are large land-and-water areas, with thick water-absorbent vegetation, surrounded by dikes, where the ground elevation is below mean sea level and engineers control the water table within the polder.

Just hardening the immediate shoreline, and especially beaches, with such structures as stone embankments to try to keep out the water won’t work well. That just makes the water push the sand elsewhere and can dramatically increase shoreline erosion.

On the other hand, creating so-called horizontal levees – with a marshy or other soft buffering area backed with a hard surface -- can be a reasonable approach to reduce the impact of storms’ flooding on top of sea-level rise.

Certainly establishing marshes (and mangrove swamps in tropical and semi-tropical coastal communities) can reduce tidal flooding and the damage from storm waves, but that may be a political nonstarter in some fancy coastal summer- or winter-resort places. Then there’s putting more houses and even stores and other nonresidential buildings on stilts, though that often means keeping buildings where safety considerations would suggest that there shouldn’t be any structures, such as on many barrier beaches. Still, it would be amusing to see entire large towns on stilts. Good water views.

Oyster and other shellfish beds can be developed as (partly edible!) breakwaters. And laying down permeable road and parking lot pavements can help sop up the water that pours onto the land. I got interested in how shellfish beds can act as a brake on flood damage while editing a book about Maine aquaculture last year. Of course, the hilly coast of Maine provides many more opportunities to enjoy a water view even with sea-level rise while staying dry than does, say, South County’s barrier beaches.

In more and more places where sea-level rise has caused increasing ‘’sunny day flooding’’ -- i.e., without storms -- streets are being raised.

I’m afraid that, barring, say, a volcanic eruption that rapidly cools the earth, slowing the sea-level rise, the fact is that we’ll have to simply abandon much of our thickly developed immediate coastline and move our structures to higher ground.

Working-waterfront enterprises -- e.g., fishing and shipping -- must stay as close to the water as possible. But many houses, condos, hotels, resorts and so on can and should be moved in the next few years. If they don’t have to be on a low-lying shoreline, they shouldn’t be there as sea level rises. For that matter, entire large communities may have to be entirely abandoned to the sea even in the lifetime of some people here.

Coastal communities and property owners face hard choices: whether to try to hold back the rising ocean or to move to higher ground. Nothing can prevent this situation from being expensive and disruptive.

Common sense would suggest that we not build where it floods and that we should stop recycling flooded properties. Again, flood risks should be fully disclosed and we need to protect or restore ecologies, such as marshes, shellfish and coral reefs and dune grass, that reduce flooding and coastal erosion.

Nature wins in the end.

Llewellyn King: It was a nice inauguration but is Biden wading in too far, too fast?

At the American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C. It would be good if President Biden addresses income inequality by touting the benefits of education in the trades as opposed to, say, getting degrees in sociology. The trades offer more secure and higher-paying jobs than do the liberal arts.

The college's model is unique in the United States, with its focus on total integration of a liberal arts and science education and the traditional building arts skills. Students choose from among six craft specializations: timber framing, architectural carpentry, plaster, classical architecture, blacksmithing and stone carving.

ACBA's mission is to educate and train artisans in the traditional building arts to foster high craftsmanship and encourage the preservation, enrichment and understanding of the world's architectural heritage through a liberal arts and science education.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It was a good day. Warm in its content. Soft in its delivery. Kindly in its message. Generous in its intentions. Healing in its purpose.

Trying to implement the soaring hopes of President Joe Biden’s inauguration began immediately. Maybe too immediately, too fast, and with actions that were too sweeping. Biden signed 17 executive orders that suggested an underlying philosophy of “bring it on.”

Biden doesn’t need to open hostilities on all possible fronts at once. He needs to pick his wars and shun some battles. I have a feeling that 17 battles are too many to initiate simultaneously and, possibly, some are going to be lost at a cost.

In his inaugural address, Biden did well in laying out six theaters where his administration will prosecute its wars. But some of those wars will go on for decades – maybe forever.

Big ships take a long time to turn around no matter how many tugboats are engaged. Actions have consequences and so do intentions.

The Biden wars:

The pandemic: This is the war that Biden must win. It is the one into which he needs to pour all his efforts, his own time and talent, and to focus the national mind.

Americans are dying at a horrendous pace. He has promised 100 million vaccine doses in the first 100 days. If that effort falters, for whatever reason, it will stain the Biden presidency. It is job one and transcends everything else.

The environment: It will remain a work in progress. Rejoining the Paris Agreement on Climate Change is a diplomatic and political move, not an environmental one. It will help with the Biden goal of better international standing. It will make many in the environmental movement feel better, but it won’t pull carbon out of the air.

There have been dramatic reductions in the amount of carbon the United States puts into the air since 2005. Biden is in danger of picking up too much of the environmentalists’ old narrative.

The environmental movement can get it very wrong and maybe has again in pushing the world too fast toward wind and solar. These aren’t perfect solutions.

The amount of carbon put into the air by electric generation in the United States is partly due to the hostility toward new dams and particularly toward nuclear power. These were features of the environmental narrative in the 1970s and 1980s.

Simple solutions seldom resolve complex problems. I have a feeling that we are going breakneck with solar and wind; making windmills and solar panels is environmentally challenging, as will be disposing of them after their useful life is over.

Canceling the Keystone XL Pipeline -- after nearly two decades of litigation, diplomatic and environmental review in Canada and the United States -- would seem to be a concession to a constituency rather than sound policy with virtuous effect.

Biden has identified three other theaters where he plans to wage war: growing income inequality, racism, and the attack on truth and democracy.

Income inequality is escalating because new technologies are concentrating wealth, workers have lost their union voice, and our broken schools are turning out broken people, who will start at the bottom and stay there. Racial inequality ditto. Many inner-city schools are that in name more than function.

If there was one big omission from Biden’s agenda of things he is prepared to go to war for, it was education. Most of the social inequalities he listed have an educational aspect. Primary and secondary schools are not turning out students ready for the world of work. Too many universities are social-promoting students who should have been held back in high school.

More are going to college when they should get a practical education in a marketable skill. People with such skills as carpentry, stone cutting, plastering, electrical and iron work are more likely to start their own businesses than those with, say, journalism or sociology degrees.

Biden’s continuing challenge is going to be how to handle the left wing of his party, stirred up by the followers of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. They haven’t gone away and are expecting their spoils from the election.

The president’s battle for truth is going to be how we accommodate the new carrier technologies of social media with the need for veracity; how to identify lies without giving into universal censorship. That battle can’t be won until the new dynamics of a technological society are understood.

Go slow and carry a big purpose.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Internet companies and freedom of speech

Google headquarters, in Mountain View, Calif.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

H.L. Mencken, journalist and essayist, wrote in 1940, “Freedom of the press is limited to those who own one.”

Twenty years later, the same thought was reprised by A.J. Liebling, of The New Yorker.

Today, these thoughts can be revived to apply, on a scale inconceivable in 1940 or 1960, to Big Tech, and to the small number of men who control it.

These men -- Jack Dorsey, of Twitter, Mark Zuckerberg, of Facebook, and Sundar Pichai, of Alphabet Inc., and its subsidiary Google -- operate what, in another time, would be known as “common carriers.” Common carriers are, as the term implies, companies that distribute anything from news to parcels to gasoline. They are a means of distributing ideas, news, goods, and services.

Think of the old Western Union, the railroads, the pipeline companies or the telephone companies. Their business was carriage, and they were recognized and regulated in law as such: common carriers.

The controversial Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act recognizes the common carrier nature of Big Tech internet companies by exempting them from libel responsibility. It specifically stated that they shouldn’t be treated as publishers. Conservatives want 230 repealed, but that would only make the companies reluctant to carry anything controversial, hurting free speech.

I think that the possible repeal of 230 should be part of a large examination of the inadvertently acquired but vast power of the Internet-based social-media companies. It should be part of a large discussion embracing all the issues of free speech on social media which could include beefed-up libel statutes -- possibly some form of the equal-time rule which kept network owners from exploiting their power for political purposes in days when there were only three networks.

President Trump deserves censure, which he has gotten: He has been impeached for incitement to insurrection. I take second place to no one in my towering dislike of him, but I am shaken at the ability of Silicon Valley to censor a political figure, let alone a president.

That Silicon Valley should shut out the voice of the president isn’t the issue. It is that a common carrier can dictate the content, even if it is content from a rogue president.

This exercise of censor authority should alarm all free-speech advocates. It is power that exceeds anything ever seen in media.

The heads of Twitter, Facebook and Alphabet are more powerful by incalculable multiples than were Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst and Henry Luce, or is Rupert Murdoch. They can subtract any voice from any debate if they so choose. That is a bell that tolls for all. They have the power to silence any voice by closing an account.

When Edward R. Murrow talked about the awesome power of television, he was right for that time. But now technology has added a multiplier of atomic proportions via the Internet.

The internet-based social media giants didn’t seek power. They are, in that sense, blameless. They pursued technology, then money, and these led them to their awesome power. What they have done, though, is to use their wealth to buy startups which offer competition.

Big Tech has used its financial clout to maintain its de facto monopolies. Yet unlike the newspaper proprietors of old or Murdoch’s multimedia, international endeavors today, they didn’t pursue their dreams to get political power. They were carried along on the wave of new technologies.

It may not be wrong that Twitter, Facebook and others have shut down Trump’s account when they did, at a time of crisis, but what if these companies get politically activated in the future?

We already live in the age of the cancellation culture with its attempt to edit history. If that is extended to free speech on the Internet, even with good intentions, everything begins to wobble.

The tech giants are simply too big for comfort. They have already weakened the general media by scooping up most of the advertising dollars. Will the freedom of speech belong to those who own the algorithms?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Thanks!1940, “Freedom of the press is limited to those who own one.”

Twenty years later, the same thought was reprised by A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker.

Today, these thoughts can be revived to apply, on a scale inconceivable in 1940 or 1960, to Big Tech, and to the small number of men who control it.

These men -- Jack Dorsey of Twitter, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, and Sundar Pichai of Alphabet Inc., and its subsidiary Google -- operate what, in another time, would be known as “common carriers.” Common carriers are, as the term implies, companies which distribute anything from news to parcels to gasoline. They are a means of distributing ideas, news, goods, and services.

Think of the old Western Union, the railroads, the pipeline companies, or the telephone companies. Their business was carriage, and they were recognized and regulated in law as such: common carriers.

The controversial Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act recognizes the common carrier nature of Big Tech internet companies by exempting them from libel responsibility. It specifically stated that they shouldn’t be treated as publishers. Conservatives want 230 repealed, but that would only make the companies reluctant to carry anything controversial, hurting free speech.

I think the possible repeal of 230 should be part of a large examination of the inadvertently acquired but vast power of the internet-based social media companies. It should be part of a large discussion embracing all the issues of free speech on social media which could include beefed-up libel statutes -- possibly some form of the equal-time rule which kept network owners from exploiting their power for political purposes in days when there were only three networks.

President Donald Trump deserves censure, which he has gotten: He has been impeached for incitement to insurrection. I take second place to no one in my towering dislike of him, but I am shaken at the ability of Silicon Valley to censor a political figure, let alone a president.

That Silicon Valley should shut out the voice of the president isn’t the issue. It is that a common carrier can dictate the content, even if it is content from a rogue president.

This exercise of censor authority should alarm all free-speech advocates. It is power that exceeds anything ever seen in media.

The heads of Twitter, Facebook and Alphabet are more powerful by incalculable multiples than were Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst and Henry Luce, or is Rupert Murdoch. They can subtract any voice from any debate if they so choose. That is a bell that tolls for all. They have the power to silence any voice by closing an account.

When Edward Murrow talked about the awesome power of television, he was right for that time. But now technology has added a multiplier of atomic proportions via the internet.

The internet-based social media giants didn’t seek power. They are, in that sense, blameless. They pursued technology, then money, and these led them to their awesome power. What they have done, though, is to use their wealth to buy startups which offer competition.

Big Tech has used its financial clout to maintain its de facto monopolies. Yet unlike the newspaper proprietors of old or Murdoch’s multimedia, international endeavors today, they didn’t pursue their dreams to get political power. They were carried along on the wave of new technologies.

It may not be wrong that Twitter, Facebook, and others have shut down Trump’s account when they did, at a time of crisis, but what if these companies get politically activated in the future?

We already live in the age of the cancellation culture with its attempt to edit history. If that is extended to free speech on the internet, even with good intentions, everything begins to wobble.

The tech giants are simply too big for comfort. They have already weakened the general media by scooping up most of the advertising dollars. Will the freedom of speech belong to those who own the algorithms?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Thanks!

Llewellyn King: Leave Big Tech alone while it’s still innovating

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When it comes to invention, we ain’t seen nothing yet.

The chances are good, and getting better, that in the coming year and the years after it, our world will essentially reinvent itself. That revolution already is underway but, as with most progress, there are political challenges.

Congress needs restraint in dealing with the technological revolution and not to dust off old, antitrust tapes. With the surging inventiveness we are seeing today across the creative spectrum -- inventiveness that has given us Amazon, Tesla, Uber, Zoom, 3D printing and, in short order, a COVID-19 vaccine – you may wonder why the government is using antitrust statutes to try and break up two tech giants.

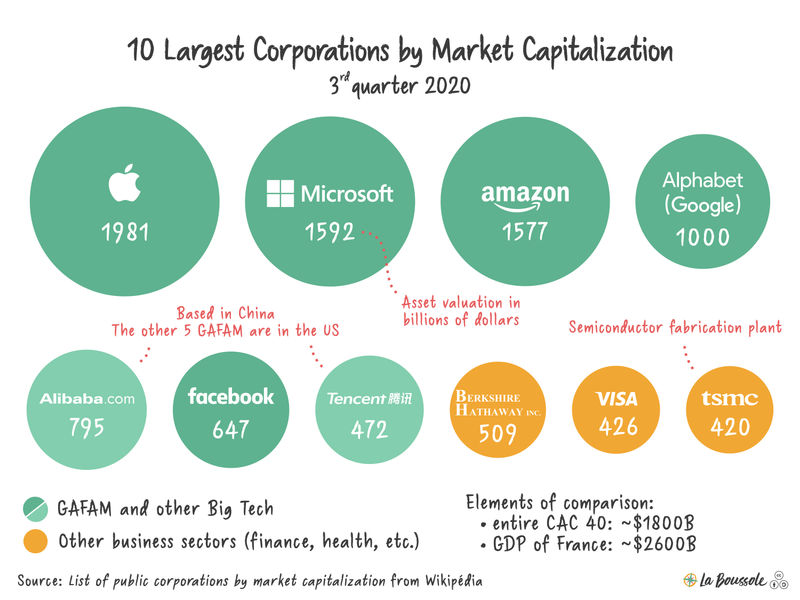

Conservatives think big social media companies are unfair to them. Liberals worry about the financial power of the Big Tech companies: The five largest have a market value of over $7 trillion.

The Justice Department has filed an antitrust suit against Google, and the Federal Trade Commission has filed one against Facebook. The only tools it has are outdated, anti-competition statutes -- some passed over a century ago. Sometime in the future, it may be desirable to disassemble Big Tech companies, but not when they are bringing forward new technologies and whole new concepts such as autonomous vehicles and drone deliveries. These need to happen without government shaking up the creators.

Antitrust laws on the books don’t address the internet age when global monopoly is often an unintended result of success; hugely different from Standard Oil seeking to have absolute control over kerosene.

Policy, though, may want to examine the role of Big Tech in relation to startups: the proven engines of change. When today’s tech giants were in their infancy, it was the beginning of the age of the startup as the driver of change. It went like this: invent, get venture-capital financing, prove the product in the market, and go public. The initial public offering (IP)) was the financial goal.

But the presence of behemoths in Silicon Valley has changed the trajectory for new companies. Rather than hoping for a pot of gold from an IPO, today’s startups are designed to be sold to a big company. Venture capitalists demand that the whole shape of a startup isn’t aimed to public acceptance but rather to whether Google, Apple or Amazon will buy that startup.

The evidence is that acquisitions are doing well in the Big Techs, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t be stifled in time. Conglomerates have a checkered past.

Big companies have a lifespan that begins with white-hot creativity, followed by growth, followed by a leveling of creativity, and the emergence of efficiency and profitability as goals that eclipse creativity. Professional managers take over from the innovators who created the enterprises; risk-taking is expunged from the corporate culture.

That is when government should look at the Big-Tech powerhouses and see whether it is in the national interest to break them up, not on the old antitrust grounds but because they may have become negative forces in the innovation firmament; because whether they are still creative or whether they are just drawing rents on previous creations or acquisitions, they will still be hoovering up engineering talents who might well be better employed in a smaller, more entrepreneurial endeavors or, ideally, as part of a startup.

The issue is simple: While the big companies are still creating, adding to the tech revolution which is reshaping the world, they should be left to do what they are doing well, from creating autonomous, over-the-road trucks to easing city life with smart-city innovation.

The time to move against Big Tech is when it ceases to be an engine of innovation.

Innovation needs an unruly frontier. We have had that, and it should be protected both from government interference and corporate timidity.

Happy and innovative New Year! Hard to believe in this time of plague, but much is changing for the better.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.