David Warsh: The expansion of women’s economic freedom that helped lead to Roe v. Wade

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

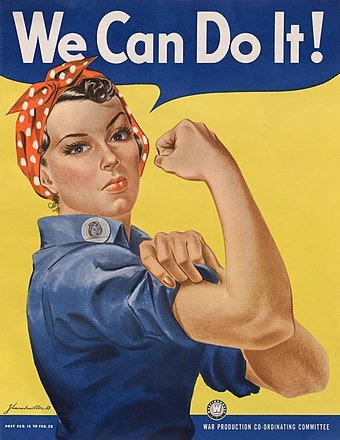

The circumstances that gave rise to the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, to establish physicians’ right to counsel the possibility of medical abortion, are not easy to recall. There was so much turmoil on the surface of things fifty years ago – Vietnam, Watergate, Richard Nixon’s landslide re-election. In retrospect, one skein of developments stands out as more momentous than the rest: the rapidly changing opportunities available to American women.

For that reason, there is no better place to start than with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin’s Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). A distinguished economic historian, Goldin organized her account around the experiences of five roughly defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the 20th Century. Each cohort merits a chapter.

The revolution, Goldin finds, was a technological one: the advent in the Sixties of dependable methods of birth control – the Pill, the IUD and the diaphragm. Women began re-entering the workforce on new terms. After explicating the traditional logic of early marriage – perhaps timeless, evolutionarily speaking – Goldin writes:

Armed with the new secret ingredient, the recipe for success became, “Put marriage aside for now. Add gobs of higher education. Blend with career. Let rise for a decade, and live tour life fully. Fold family in later.” Once this happiness formula was adopted by large numbers of women, the age at first marriage increased, even for college women who did not take the Pill. That reduced the potential cost of long-run cost of marriage delay for any one woman.

With that, the 7-2 majority decision in Roe v. Wade was almost an afterthought. The Supreme Court doesn’t just follow the election returns; they have families, and read the newspapers as well. .

Since 1982, the Federalist Society, conservative legal representatives of that year’s “Silent Majority,” have been working to reverse the decision by fundamentally transforming the judicial interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. You can read historian David Garrow’s triumphant summary of these “originalist” and “textualist” movements here.

Meanwhile, a May 7 Boston Globe story (subscription required) about Sir Matthew Hale, the 17th Century jurist whom Associate Justice Samuel Alito cited more than a dozen times in his 98-page draft opinion, makes equally interesting reading. Reporter Deanna Pan may have surfaced another plausible reason that the draft was leaked.

If experience is any guide, the next twenty-five years will see an avalanche of work on the other side of the argument, produced by legal scholars, historians, economists and other social scientists. Quite apart from whatever the election returns in the coming years might be, a movement to explain changing values and preferences has been underway in economics for years. New views on the joint evolution of institutions and cultures are entering the mainstream.

The Supreme Court is one of those institutions – central banks are another – to which democratic societies have delegated decision-making powers in the hope that in difficult times they will make more far-sighted policy choices than those of the current majority.

The court decided Roe v, Wade correctly in 1973. In all likelihood, it will sooner or later rise to the occasion again, In the meantime, stay calm; plan ahead, and cope with consequences if the expected reversal eventuates. Don’t throw the Supreme Court baby out with the bathwater.

David Warsh a veteran reporter, columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Chris Powell: Liberals extol precedent when it serves them

U.S. Supreme Court Building.

Liberals throughout the country applauded three years ago when, proclaiming that the U.S. Constitution requires states to confer same-sex marriage, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed 44 years of precedent in constitutional law as well as practice going back to the adoption of the Constitution, in 1789.

Liberals in Connecticut also applauded three years ago when the state Supreme Court ruled capital punishment unconstitutional, thereby reversing the state and federal constitutions themselves, which always have explicitly authorized capital punishment and still do.

But a few weeks ago liberals criticized the U.S. Supreme Court for reversing its 41-year-old decision holding that government agencies could require their employees to pay dues to unions they didn't want to join. The precedent should have stood, liberals said, because it was precedent and much policy had grown up around it.

And now that President Trump's nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court is suspected of inviting a challenge to the abortion rights declared in the court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, liberals -- including Connecticut Democratic Senators.Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy -- again are freaking out about possible disrespect for precedent. But Roe itself also reversed precedent going back to 1789, since prior to Roe abortion law always had been left to the states.

Of course when it comes to the Supreme Court these days respect for precedent doesn't really concern liberals or conservatives. Their concerns are only policy and power. If precedent gives them policy and power, they support it. If it doesn't, they oppose it.

With the court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren Court in the 1950s and '60s liberals began elevating their policy desires to constitutional requirements, since constitutionalizing an issue could push democracy out of the way when it became inconvenient. Now that they are in power nationally, conservatives are playing this game too.

As a result the country is being led to believe that the Constitution is just anyone's wish list, requiring whatever one likes and prohibiting whatever one dislikes, led to believe that there is no distinction between what the Constitution says and what policy should be.

But contrary to the suggestion of Connecticut's senators, Gov. Dannel Malloy, and other leading Democrats, there is no danger that the U.S. Supreme Court will criminalize abortion. For the court has no such power. Even if the court reverses Roe, abortion policy would just return to the states and Congress.

Connecticut generally favors legalizing abortion, at least prior to fetal viability, and so state law permitting abortion likely would be preserved. But state law on abortion goes against public opinion by letting minors obtain abortions without the consent of their parents or guardians, even as this policy has concealed the rape of minors. Ironically, while waiving parental consent for minors getting abortions, Connecticut law requires it for minors getting tattoos.

Startling as it might seem in Connecticut, opinion in some states is hostile to abortion and opinion nationally would prohibit late-term abortion, which the Roe decision itself indicated states could do. Further, many legal scholars who support legal abortion acknowledge that, as a matter of law, Roe was mostly judicial contrivance.

But Democrats seem to think that they can win on this issue only by generating enough hysteria to prevent any honest discussion that recognizes distinctions.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.