Llewellyn King: A shrug when it comes to mass murder with guns

AR-15-style assault rifle made by Southport, Conn.-based Sturm, Ruger & Co.

A Smith & Wesson AR-15-style assault rifle, designed to tear apart as many people as possible as fast as possible.

In Maryville, Tenn., where long -Springfield, Mass.-based gun maker Smith & Wesson’s is moving its headquarters. The company makes assault rifles beloved by mass murderers. That has bothered folks in Massachusetts but makes the company popular in gun-cult-dominated Tennessee and other violent Red States.

— Photo by Brian Stansberry

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Murder most foul,” cries the ghost of Hamlet’s father to explain his own killing in Shakespeare’s play.

We shudder in the United States when yet more children are slain by deranged shooters. Yet we are determined to keep a ready supply of AR-15-type assault rifles on hand to facilitate the crazy when the insanity seizes them.

The murder in Nashville of three nine-year-olds and three adults should have us at the barricades, yelling bloody murder. Enough! Never again!

But we have mustered a national shrug, concluding that nothing can be done.

Clearly, something can be done; something like reviving the assault rifle ban, which expired after 10 years of statistically proven success.

We are culpable. We think that our invented entitlement to own these weapons, designed for war, is a divine right, outdistancing reason, compassion, and any possible form of control.

The blame rests primarily on something in American exceptionalism that loves guns. I mostly understand that; I like them myself, as I write from time to time. I also like fast cars, small airplanes, strong drink, and other hair-raising things.

But society has said these need controls — from speed limits to flying instruction — and has severe penalties for mixing the first two with the last. Those controls make sense. We abide by them.

When it comes to that other great national indulgence, guns, society has said safety doesn’t count. So far this year, more than 10,000 people have been killed in gun violence. If that were the number of fatalities from disease, we would again be in lockdown.

We have concocted this scared right to keep and use guns. To ensure this, the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been manhandled by lawyers into being a justification for putting something deadly out of the reach of social control or even rudimentary discipline.

The latest school shooting has raised our hackles, but not our capacity to act. This national shrug at something which can be fixed is a stain on the body politic.

Most of the conservative wing of the establishment, represented by the Republican Party, has dismissed it as one might a natural disaster.

But the routine murder of innocents in school shootings is a man-made disaster. Worse, it is sanctified by a particular interpretation of the Second Amendment.

It is an interpretation which has demanded, and continues to demand, legal contortionism. This is used to justify the citizenry owning and using weapons of war.

This latest school shooting, which happened in this young year, was shocking, but what was more shocking was the political reaction.

President Biden wrung his hands and said nothing could be done without the support of Congress — thus endorsing a national fatalism.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina suggested more policemen in schools, and Rep. Thomas Massie (R.-Tenn.) said teachers needed to be armed. His children are homeschooled.

In personal life and in national life perceived impossibility is hugely debilitating.

Imagine if the Founding Fathers had said the British Empire was too strong to challenge, if FDR had said America couldn’t rise against the forces of the economic chaos of the 1930s, or if Margaret Thatcher had said British trade unions were too strong to be opposed?

These are incidents where perceived reality was, with struggle, trounced for the general good.

Guns along with drugs are the largest killer of young people. They aren’t unrelated. Unregulated guns find their way to the drug gangs of Central America, facilitating the flow of drugs.

On the Senate floor, the chamber’s longtime chaplain, retired Rear Adm. Barry C. Black, took on the pusillanimous members of his flock after the Nashville murders, quoting the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s admonition, “The only thing needed for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.” Indubitably.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Nyla Samee, Khury Petersen: Past time to go after the gun makers

Springfield, Mass.-based Smith & Wesson’s M&P15-22 semiautomatic rifle

Via OtherWords.org

There is a familiar pattern after the mass shootings that have become a well-known feature of American life.

The initial shock and grief gives way to demands for greater regulation of gun ownership by Democrats, while Republicans dismiss such measures and blame mental illness instead. But if we actually want to do something about it, we need to have new conversations.

We often talk about where and how weapons are purchased — but rarely where and how they are manufactured. These realities challenge the conventional way we talk about guns in terms of a “culture war” between red and blue states.

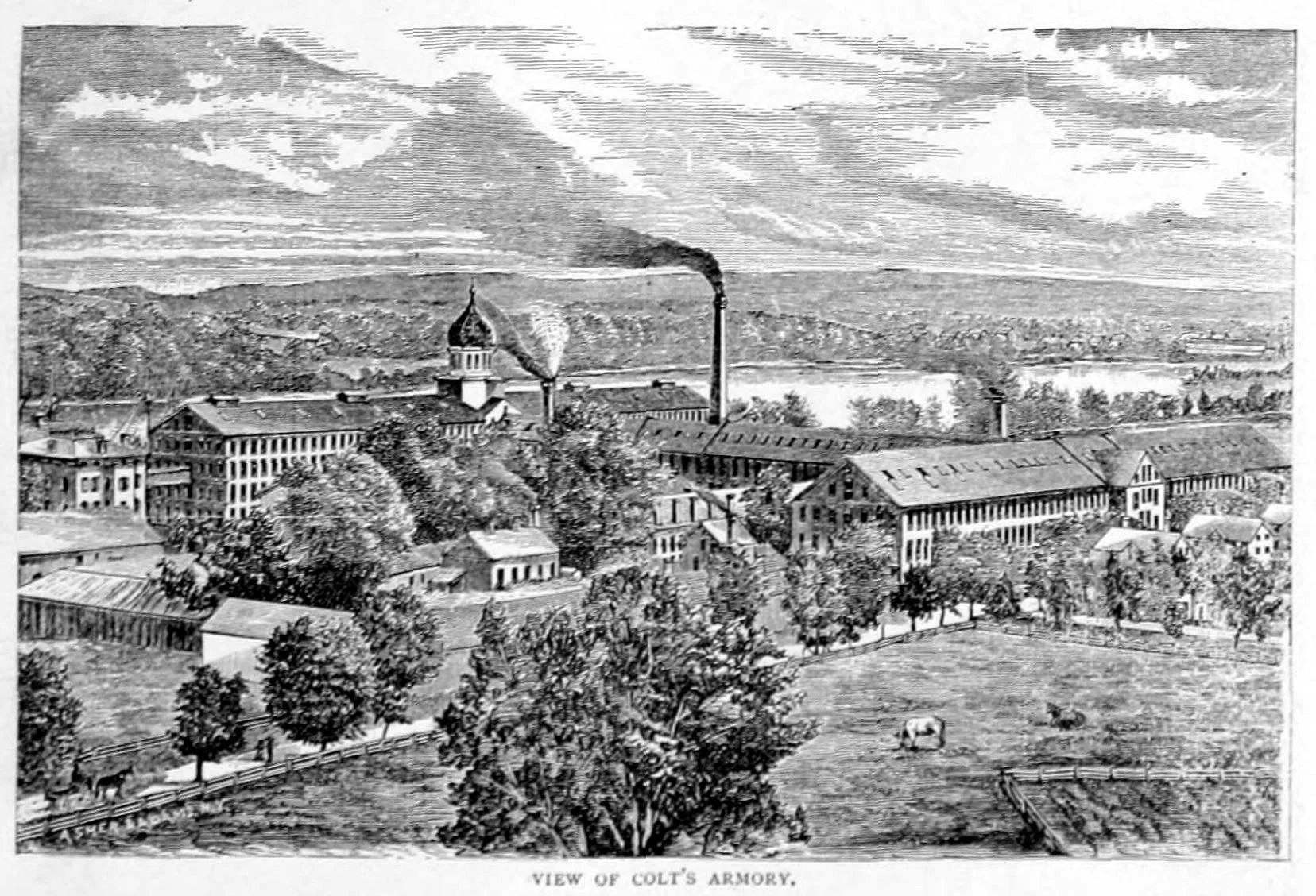

1896 lithograph of Colt’s Manufacturing Co.’s factory and headquarters, in Hartford. The company is now based in West Hartford.

For example, the Blue states of Massachusetts and Connecticut have some of the strictest regulations on firearms carrying and possession. But they are also major sites of gun manufacturing in this country. The weapons used in the 2018 Parkland shooting, for example, were manufactured by Smith and Wesson, a gun manufacturer based in Springfield, Mass.

The deeper and bigger point is that the U.S. is the world’s principal supplier of weapons.

The U.S. weapons industry makes both heavy weapons, such as military aircraft, bombs, and missiles, and small arms like rifles and handguns. As of 2021, over 40 percent of the world’s exported arms came from the United States — many of them manufactured in deep blue states.

Blue states with strict gun laws often suffer gun violence when weapons are trafficked in from Red states with looser gun laws. Similarly, many countries surrounding the U.S. with high rates of gun violence, such as Mexico, obtain guns both legally and illegally from this country.

With no system to effectively control and track who ends up with those guns, these weapons are often obtained by military units or police that have committed human rights abuses or who work with criminal groups.

For example, in September 2014, local police in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, were responsible for the disappearance and murder some 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College. The police were armed with rifles that were supplied legally from Colt, a prominent U.S. gun manufacturer based in Connecticut.

Most Americans, including most gun owners, support some level of gun control or background checks. But gun lobbies such as the NRA, which are so influential in Red states, don’t really represent gun owners — they represent gun manufacturers. In fact, of the NRA’s corporate partners, several are gun manufacturers based in Blue states.

As long as these corporations flood the U.S. and the world with guns, debate over who accesses these guns won’t get us very far.

So our current conversation serves the status quo. It further divides people in this country according to a “culture war” narrative, where politicians clash in rhetoric, but everyone knows that the actual situation will not change.

From the perspective of ending bloodshed, this isn’t working. We need to try something different, and it will mean some deeper interrogation about where these weapons come from.

This could mean reviewing the practices and impacts of gun manufacturers, demanding greater regulation, and — as with any product that causes far reaching harm — having a public conversation about whether companies should be allowed to make these weapons at all.

The mass production of guns has been a disaster — one that has dire consequences not only for U.S. communities, but for those all over the world. New ways of thinking will help us fulfill our responsibility to protect vulnerable people not just in the U.S., but people everywhere.]

Nyla Samee is a Next Leader at the Institute for Policy Studies, where Khury Petersen is an fellow.