John O. Harney: N.E.’s changing ethnic demographics; shrinking police forces; honorary degrees and culture wars

1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Population studies. The U.S. Census Bureau released new population counts to use in “redistricting” congressional and state legislative districts. Delayed by the pandemic, the counts came close to the legal deadlines for redistricting in some states, raising concerns about whether there would be enough time for public input.

The U.S. population grew 7.4% in 2010-2020, the slowest growth since the 1930s, according to the bureau. The national growth of about 23 million people occurred entirely of people who identified as Hispanic, Asian, Black or more than one race.

The Associated Press reported:

The population under age 18 dropped from 74.2 million in 2010 to 73.1 million in 2020.

The Asian population increased by one-third over the decade, to stand at 24 million, while the Hispanic population grew by almost a quarter, to top 62 million.

White people made up their smallest-ever share of the U.S. population, dropping from 63.7% in 2010 to 57.8% in 2020. The number of non-Hispanic white people dropped to 191 million in 2020.

The number of people identifying as “two or more races” soared from 9 million in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020, accounting for about 10% of the U.S. population.

A few New England snippets

Maine remains the nation’s oldest and whitest state, even though it saw a 64% increase in the number of Blacks from 2010 to 2020, as well as large increases in the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Connecticut’s population crawled up 0.9% over the decade from 2010 to 2020 to 3,605,944 residents. The number of residents who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) increased from 29% of the population in 2010 to 37% in 2020. Connecticut’s number of congressional seats won’t change, but district borders will.

The total population of the only city on Boston’s South Shore, Quincy, Mass., topped 100,000 (at 101,636), as its Asian population grew to represent nearly 31% of all residents. Further south, the city of Brockton’s population increased by nearly 13% as the white population dropped by 29%, and the Black population increased by 26%.

Amazon jungle. Amazon last week announced it will pay full college tuition for its 750,000 U.S. hourly employees, as well as the cost of earning high school diplomas, GEDs, English as a Second Language (ESL) and other certifications. While collecting praise for its educational goodwill, stories of dire conditions in the e-commerce giant’s workplace also triggered a new California law that would ban all warehouses from imposing penalties for “time off-task” (which reportedly discouraged workers from using the bathroom) and prohibit retaliation against workers who complain.

Police shrink. Police forces in New England have recently felt new recruitment and retention pressures. In August 2021, The Providence Journal ran a piece headlined “Promises made, promises delivered? A look at reforms to New England police departments.” GoLocal reported that month that Providence policing staff levels stood at 403, down from 500 or so in the 1980s under then-Mayor David Cicilline. The number of officers employed by Maine’s city and town police departments and county sheriffs’ offices shrank by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2020, according to the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Reporter Lia Russell of the Bangor Daily News noted, “It’s also a challenge that police in Maine are far from alone in facing, especially following a year during which police practices across the nation were called into question following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin.” The Burlington, Vt., City Council in August defeated efforts to reverse a steep cut in city police ranks. The police department currently has 75 sworn officers, down from 90 in June 2020. A survey by the police officers’ union found that roughly half of Burlington cops were actively seeking employment elsewhere.

Honor roll. Honorary degrees are becoming something of a frontline in the culture wars. Springfield College alumnus Donald Brown, who recently coauthored a piece for NEJHE, tells of his alma mater revoking the honorary master of physical education degree it had bestowed on U.S. Olympic Committee Chair Avery Brundage in 1940. In 1968, Brundage pressured the U.S. to take action against two Olympic athletes who gave the Black Power salute after finishing first and second in the 200 meters. That event was only the tip of the iceberg. Brundage had a history of anti-semitism, sexism and racism. Springfield President Mary-Beth Cooper met with the trustees and others and decided to take back the honor. Meanwhile, the University of Rhode Island has been tying itself in knots over the honorary degree it bestowed on Michael Flynn in 2014, before he was appointed Trump’s national security adviser and accused of sedition.

Refugees. After the U.S. ended its longest war (so far) in Afghanistan and the capital of Kabul fell, the question arose of where Afghan refugees would resettle. New England cities, including Worcester, Providence and New Haven, are among those that have readied plans to welcome Afghan refugees. In higher education, Goddard College President Dan Hocoy said it was a “no-brainer” to offer to house Afghan refugees at its Plainfield, Vt., campus for at least two months this upcoming fall. Back in 2004, NEJHE (then Connection) featured an interview with Roger Williams University President Roy J. Nirschel, who died in 2018, and his former wife Paula Nirschel on the university’s role in its community as well as their pioneering initiative to educate Afghan women.

Sunshine state. Before Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took his most recent stand against fighting COVID, he displayed a narrow-mindedness that seems to always be in fashion. As Inside Higher Ed reported, after expressing concerns about faculty members “indoctrinating” students, DeSantis signed a law requiring that public institutions survey students, faculty and staff members about their viewpoint diversity and sense of intellectual freedom. The Miami Herald reported that DeSantis and state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, the original bill’s Republican sponsor, suggested that the results could inform budget cuts at some institutions. Faculty members have opposed the bill, which also allows students to record their professors teaching in order to file free speech complaints against them.

New colleges in a time of contraction. The nonprofit Norwalk (Conn.) Conservatory of the Arts announced plans to open a new performing-arts college and welcome its first class in August 2022. It’s unusual news amid the stream of college mergers and closures only widened by the pandemic. Among the challenges, many of the faculty members don’t have master of fine arts degrees that accrediting agencies require and, without accreditation, the college’s students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or Pell Grants.

The Conservatory says the college will consolidate a traditional four-year undergraduate program into two years of intense training and a two-year graduate program into one year. Meanwhile, up the coast, the (Fall River, Mass.) Herald News reports that Denmark-based Maersk Training and Bristol Community College will work together to turn an old seafood packaging plant in New Bedford, Mass., into a National Offshore Wind Institute training facility to train offshore wind workers, complete with classrooms and a deepwater pool to train and recertify workers. (NEJHE has reported on the need to train talent for the burgeoning industry and the coastal economy’s special role in New England.)

Other higher-ed institutions are shapeshifting. After months of discussions and lawsuits, Northeastern University and Mills College reached agreement to establish Mills College at Northeastern University. Founded in 1852, Mills is renowned for its pre-eminence in women’s leadership, access, equity and social justice. Also, billionaire investor Gerald Chan and his family’s Morningside Foundation gave $175 million to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which will be renamed the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. That’s the largest-ever gift to the UMass system.

Land deals. I was recently struck by a report titled We Need to Focus on the Damn Land: Land Grant Universities and Indigenous Nations in the Northeast. The report was born of a partnership between Smith College students and the nonprofit Farm to Institution New England (FINE) to look at how land grant universities view their historic relationships with local Indigenous tribes and how food can play a role in repairing those relationships. It grabbed my attention, partly because NEJHE has published some interesting stories about Native Americans and New England higher education. (See Native Tribal Scholars: Building an Academic Community and A Different Path Forward, both by J. Cedric Woods and The Dark Ages of Education and a New Hope, by Donna Loring.) And partly because two NEBHE Faculty Diversity Fellows, professors Tatiana M.F. Cruz of Simmons University and Kamille Gentles-Peart of Roger Williams University, are spearheading a fascinating Reparative Justice initiative. Among other things, Cruz and Gentles-Peart have had the courage to remind us that land grant universities in New England occupy the land of Indigenous communities. The Smith-FINE work offered sensible recommendations: Financially support Native and Indigenous faculty, activists, programs on campuses and beyond; offer free tuition for Native American students; hire Indigenous people, and fund their research.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Donald Brown/Sherry Earle: Springfield College’s Legacy Alumni of Color

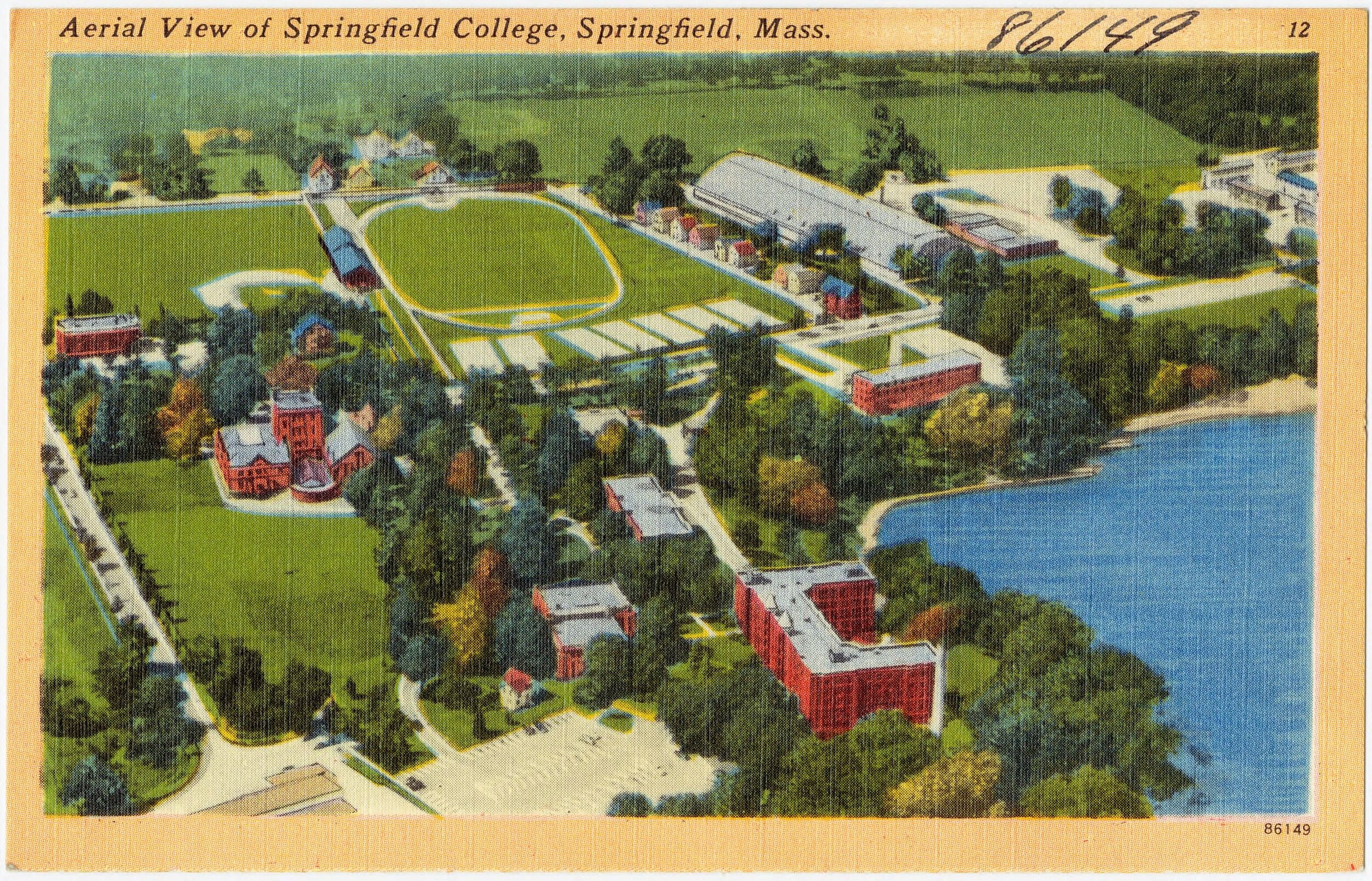

Old postcard

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

In 1966, Jimmy Ruffin sang “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted?” This song resonates with us and many of our colleagues whose hearts were broken 55 years ago at our alma mater, Springfield College …

Virtually every Black student at the college in those days felt unwelcomed. Not only was there a dearth of Black faculty, but there were also virtually no administrators of color and no support services to address the needs of the dozen Black students on campus.

This was a time when Muhammad Ali refused the military draft. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. John Carlos and Tommy Smith raised their fists in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics. Students of color throughout the country were demonstrating for equality and fair treatment on their campuses.

These epochal events were not lost on Black students at Springfield College. In 1969, we took over the administration building and the following year occupied a dormitory. As a result, virtually all of those who participated in the dormitory takeover were suspended from the college. Brokenhearted, most of them walked away from Springfield College not to be heard from again for 50 years.

A half-century later, I observed the racial tumult of 2020 and reflected on our experience in the 1960s. For it was then that I had an idea. I would check with a few of my sisters and brothers with whom I had shared this undergraduate experience. I began making calls asking if they would reach out to others to see if there was any interest in a Zoom conference call to generally catch up on their life journeys and to ask them how they felt about today’s Springfield College. To my surprise, everyone who was called wanted to meet. I was ecstatic.

Through the process of making calls about a possible reconnect, I and others learned that while Springfield College now has more than 300 Black and Brown full-time undergraduates, these students still have issues that demand attention from the college. These are issues that have frustrated Black students dating back to the days when there were only a handful of Black students, and virtually no Brown students at all on campus. So, in March 2020, my brother and sister alumni began meeting with current leaders of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) students. We decided that to support BIPOC students and influence change at the college, we needed to create a formal group. Hence, the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College was born.

Out of a burning concern to ensure a better experience for Springfield College BIPOC students, our group decided to set up five committees focused on: Mentoring, Public Safety/Student Relations, Coaching/Faculty, Day of Diversity, and Distinguished Alumni. Each committee developed a plan of action in their respective areas. Based on committee input, the Legacy Alumni, in turn, crafted an 18-page report entitled: “Legacy Alumni of Color: A Blueprint for Change” and sent it to the president of the college, Mary-Beth A. Cooper. Responses to all of our recommendations were soon forthcoming. Overwhelmingly, the Legacy Alumni were pleased with the college’s responses to our recommendations.

Listed below are just a few of the recommendations made by the Legacy Alumni of Color.

1. Increase ethnic diversity on the senior leadership team to set an example for the college.

2. Build a pipeline to develop BIPOC students for positions in administration, teaching and coaching.

A. Begin with programs for middle school and high school BIPOC students.

B. Conduct a college-sponsored summer institute to develop BIPOC candidates.

C. Continue the mentorship work begun by the Alumni Office.

D. Continue work with NCAA initiatives on diversity and inclusion.

• Have coaches review the 2020 NCAA Inclusion Summer Series and past Equity and Inclusion Forums.

• Have the college sign the Eddie Robinson Rule to ensure that departments of athletics pledge to “interview at least one, preferably, more than one, qualified racial and ethnic minority candidate” for open head coaching jobs.

• Continue participation in the NCAA Ethnic Minority and Women’s Internship program.

• Participate in upcoming NCAA programs to advance racial equity.

3. Improve recruitment of BIPOC students by increasing the diversity of staff in the Office of Undergraduate Admissions.

4. Increase staff and provide adequate funding for the Office of Multicultural Affairs in order to continue the important work of the office to create an inclusive campus, support BIPOC students and address issues of social justice.

5. Include the Office of Multicultural Affairs on tours when prospective students visit the campus.

6. Ensure that members of underrepresented groups are included on all hiring committees.

7. Hire a person of BIPOC descent in the Counseling Center.

8. Hire a person of BIPOC descent in the Office of Spiritual Life.

9. Continue to archive oral histories of BIPOC student experiences at Springfield College.

10. Strengthen ties with the off-campus community by sponsoring and hosting activities and events.

A. Support community service currently conducted by student-run organization such as Women of Power’s supply drive for the YWCA.

B. Increase ties to Springfield’s very active Black religious community.

C. Recruit BIPOC students from Springfield’s middle and high school for on-campus events.

D. Continue to send college staff to provide technical assistance to off-campus community groups.

11. Conduct an annual climate-of-life survey to learn what the experience has been for BIPOC students.

12. Require all entering students take the newly created course in ethnic studies beginning in the fall 2021.

13. Increase funding for existing student-run associations that support BIPOC students. Provide seed money to launch new student-generated associations.

A. Adequately fund the Men of Excellence program to empower men through development of leadership skill, pride and humility

B. Support the Student Society for Bridging Diversity, originally created as the African American Club in the 1980s, to recognize and accept all members of the human race.

C. Support women on campus and in the community through Women of Power group.

14. Make A Day to Confront Racism an annual event to address power, privilege and prejudice. Allocate sufficient funds to engage a speaker with standing equal to that of Ibram X. Kendi, this year’s speaker.

15. Continue the work of the Committee on Public Safety to reduce tension and misunderstanding in interactions between BIPOC students and Public Safety Staff (PSS).

A. Provide name badges for all PSS.

B. Conduct twice yearly dialog groups between BIPOC students and PSS.

C. Complete evaluation sheets following these dialogs to set the agenda for further work.

D. Continue anti-bias training for PPS staff.

16. Prominently display recognition of distinguished BIPOC alumni.

17. Ensure continued progress by issuing a twice annual scorecard on measurable progress made on these and other recommendations emanating from the “Legacy Alumni of Color: A Blueprint for Action” report and continuing feedback.

We believe that the Legacy Alumni of Color has done something at Springfield College that no other school in the nation has done. We returned to our alma mater to help fashion a welcoming, inclusive environment for students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

So, that’s what became of these brokenhearted. Not a bad outcome, not a bad start.

Donald Brown is the former chair of the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College and the president & CEO of Brown and Associates Education and Diversity Consulting and former director of the Office of AHANA Student Programs at Boston College. Sherry Earle is a member of the Legacy Alumni of Color of Springfield College and a teacher of gifted children in Newtown, Conn.

Editor’s Note: Donald Brown wrote “What Really Makes a Student Qualified for College? How BC Promotes Academic Success for AHANA Students” for the Spring 2002 edition of NEJHE‘s predecessor, Connection: The Journal of the New England Board of Higher Education.

The indoor sport invented in response to New England winters

The first basketball court, at what became Springfield College

“The invention of basketball was not an accident. It was developed to meet a need. Those boys would not simply play ‘Drop the Handkerchief.’’’

James Naismith, the inventor of basketball, on his time at Springfield College

In December 1891, Naismith, a Canadian-American physical-education professor at the International Young Men's Christian Association Training School (today, Springfield College) in Springfield, Mass., sought to create a vigorous indoor game to help keep his students occupied and fit during the long New England winters. After rejecting other ideas as either too rough or poorly suited to gymnasiums, he wrote the basic rules and put up a peach basket.

The Basketball Hall of Fame, in Springfield