‘From the cellar stairs’

Union Village, in Thetford, Vt: Methodist church and defunct School House.

Photo by EdwardEMeyer

“I was happy, but I am now in possession of knowledge that this is wrong. Happiness isn't so bad for a woman. She gets fatter, she gets older, she could lie down, nuzzling a regiment of men and little kids, she could just die of the pleasure. But men are different, they have to own money, or they have to be famous, or everybody on the block has to look up to them from the cellar stairs.”

— Grace Paley (1922-2007), American writer. A native of New York City, she lived in Thetford, Vt., in her later years.

Thetford in 1912.

William T. Hall: Surviving the swarm

Text and watercolor painting by William T. Hall, a Florida-and-New England-based painter and writer

As we endured one of our family weeding sessions in our vegetable garden in Thetford, Vt., my grandfather said abruptly, and with strong emphasis, the four-letter “S-word”. It was enough of a surprise to lead grandmother to remind him that children were present. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Harold, your language – please!”

We all stared at Gramps as Grandmother looked over her glasses at my mother, who was smiling at her while fighting with a deep-set weed. Mother’s garden glove was full of a dozen or so vanquished weed specimens dropping dust as she looked over to me, rolling her eyes. I could see my reflection in her sunglasses as my little brother, Steve, leaned in and whispered to me , while wagging his index finger at the ground, “Naughty-naughty, Gramps”

“What’s wrong, Dad?” my mother asked. “You okay?”, she asked, as she pulled on another stubborn weed.

He said nothing as he set his jaw and unfolded his tall frame upward from his kneeling position like a camel standing up in the desert. He was looking at the top of his wrist as if to check a watch that wasn’t there. In that hand he held a big red Folger’s coffee can half-filled with kerosene into which he had been dropping hundreds of Japanese Beetles. These he had picked meticulously from the leaves of his potato plants. This sort of thing defined one of his methods for guarding against pests in the modern age of pesticides. “Better to pick’m off and get’m before they get you.”

After he had stood up fully, he looked perplexed, as if he didn’t believe what had just happened. He looked at my grandmother and said one word,

“Bee.”

“Sting?“ My mother asked.

“No he just scratched me a — warning”.

This we all knew from being on the farm. When you work around bees they are busy, too, gathering honey. Unless you create too much commotion around bees or otherwise make them too anxious, a human usually gets a (warning) a scratch before a (sting).

A warning was when a bee dragged his stinger across your skin to give you what felt like a little hot spark. A full “sting” was, of course, much more painful and was delivered with a bee’s ultimate strength, resulting in the hooked end of the stinger deep under the skin with the bee’s abdomen still attached to feed the stinger with venom. This added to your pain immensely. For this one extreme act, the honeybee pays with its life, and for allergic recipients, the sting can cause anaphylactic shock. To that person multiple stings all at once could cause death.

To my grandfather this “scratch” seemed like an unprovoked over-reaction, and he didn’t understand what he had done to deserve it.

Harold had been stung several times in his life but he understood that each time he’d done something provocative. When he saw that there were lots of other bees around us not harming us, it seemed as if nothing menacing had happened, so what was the big deal? Grandpa was insulted. He shook his head. My mother, teasing her father, asked him, “Dad, did you make a mistake? You know the difference between a Japanese beetle and a bee right”?

We all laughed and looked at my grandfather, wanting to gauge his reaction to my mother’s tease. He held the coffee can in one hand and laughed politely at the ribbing. He was always a good sport.

“I’m glad I didn’t sit on him”, he said and got a double-good laugh from all of us.

But as he was looking at us he was still wondering why there seemed to be so many bees everywhere in the air. They swirled like embers from a campfire. It was a busy confusion in orange, black and tan reminding him of when he attended his mother’s beehives at their turkey farm in Walpole, Mass., years before.

“Gramps! What’s is that?” asked my brother Steve he excitedly pointed to the sky above and behind Gramp’s silhouetted upper torso.

“Harold!” My grandmother shouted sharply, my grandfather and the sky above him reflecting in her glasses.…

Gramps looked at her perplexed as he turned to see what she meant. Something amazing and frightening was happening in the sky behind him. He had never seen anything like it before, and nor would he ever again. He looked back in awe at a jet-black roiling cloud in the sky over the Connecticut River. “It’s bees!”Then suddenly,“ SWARM!” he yelled as he set down his coffee can.

“What the heck!?” My mother exclaimed as she stood up, dropping her spade and the weeds from her gloves.

“Gloria, Quick help me up!” my grandmother yelled. My mother said frantically, in a commanding voice, to Steve and me, “Kids, get your grandmother up and head to the house”! As we helped our 200-pound grandmother to her feet, our mother rushed to her father’s side asking. “What should we do? Dad?”

They both looked up at the cloud and now we all could hear the sound of the bees, which mimicked the sound of a breeze blowing through tree leaves.

My grandfather mumbled something unintelligible in Swedish under his breath.

“Pop, in English!”, my mother asked in a slightly panicked tone. “What should we do?”

Without taking his eyes off the swarm, Gramp said, “Yes, get Lillian to the house, but don’t run, Ok? Just walk fast and don’t panic. We must not spook the swarm. Look at them! They look pretty riled alread.”

“Harold, you be careful,’’ my grandmother said.

“We’ll be fine, ’’ he said.

“Somewhere in the middle of the swirling mass is the Queen. Bees will do anything to protect their Queen. They’re looking for a new hive. These other bees down here are the scouts”.

Our farm was on the floor of Vermont’s Upper Connecticut River Valley about a football field’s length from the river and a mile’s south of the village center of Thetford. Our barn was in the middle of our property between two 25-acre fields, with two big shade-maple trees taller than any other trees next to the barn, which was four stories tall, from the basement to the peak of the open hayloft.

The whole barn structure was basically open. It was June, and the barn was empty of hay. There was one window in the peak and an open hay door in the end. The barn was designed to suck air in at the basement pig stalls on the backside of the building and to direct it inward and upward out through the big open barn doors and hay doors in both peaks. Those doors were 16 feet tall and were at the top of the earthen ramp that led to the second story. The ramp was designed for horses pulling full hay-wagons up into the big main hay-storage room. The main room was enormous, about 40 by 60 feet and 45 feet to the peak, where the hay trolley track and unloading-fork still hung covered in cobwebs.

Grandpa knew that the swarm of bees high in the air above our barn probably saw what looked like the perfect place for new beehive — a place with the perfect size and shape to house what seemed like a zillion tired and desperate bees and their queen.

My grandfather could see this in the few moments he had to scope out the problem and he understood that the welcome mat would be out until he could close up the barn to keep out these unwelcome guests.

Gramps now could hear the house windows being slammed down shut and the garage door being closed in the long shed off the main house. The ladies had done their job. The house would be a secure hiding place for the family no matter what happened in the other buildings. Grandpa’s carpentry shop, the hen house, a little stone milk-house and our barn were the only possible manmade homes for the bees.

The area directly above and behind the barn was a jet-black fuzzy moving mass. The swarm covered the whole width of the house, barn and shade trees. The scene reminded Gramps of the sand-and-soil clouds during the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Like those roiling clouds, the cloud of bees had a dark and menacing look.

Like a monster in the sky, the cloud seemed to lurch forward, north up the river, and then roll back on itself down the river as if there was dissension in the cloud of bees.

The air around us was still filled by a blizzard of bees, but even though we were occasionally scratched by the frantic scouting insects, we did not feel in danger. We could see their dilemma. We did not want to make their plight any worse than it was, but they could not have our barn, from which it would have taken months and lots of money to dislodge them. Worse, many bees would die in the removal. Maybe the bees could feel this, or maybe they were totally unaware of us, but they continued to leave us alone.

Gramps knew that with any flood of living things — humans, cattle, turkeys, fish and so on, only so many of them could get through a restricted opening at once without catastrophic results.

They had only their instinct to protect and nurture their queen. Each individual bee was devoted to its queen first, then secondly to the whole hive. Beyond that simple reality they had not evolved.

They were incapable of leaving her but confused about where to take her. At this point they seemed at a crossroads.

“Billy, go to the basement of the barn and close all the pig-pen doors down there,’’ Gramps told me. “Make sure the bees can’t get through any cracks. Throw hay at the bottom of the doors to close up the gap. Then meet me at the front ramp and we’ll close the big doors together. We can get to the windows last. Listen to me.…If this all turns bad, then get to the house and your mother will know what to do”.

“Where are you going, “ I asked.

“I’ll go to my shop and see if I can close it up. It’s wide open”.

“What about the chickens,” I asked.

“I don’t know? They eat bugs. They’ll have to fend for themselves”.

The cloud of bees was hanging over the rear pasture and getting closer to the barn by the minute, casting a dull shadow as when a cloud causes a shadow in the valley. I did get stung when I closed the last pig-pen door and I put my hand right on a bee. It hurt, but I sucked on the spot and kept moving.

When I got to the big doors in the front of the barn, grandfather was there. He’d rolled the burn-barrel up the ramp, saying that would be a last resort. He would start a smudge fire in the barrel to smoke out the incoming bees if it became necessary. The thought of any open fire in our barn made us both sick to think about. “Would you really risk that”, I asked my grandfather.

“No. I don’t think so, but we’ll see”.

As we rolled the barrel into place, something in the changing sky caused a shift on what had been sun-lit ground to scattered shadows there. With that change came a slight drop in temperature.

The moment seemed to signal something within the swarm. The bees moved. They roiled northward, and then suddenly their pace increased and they seemed to rise up farther. There was a bulge in the front of the cloud as it headed up river. The swarm passed over the iron bridge a half mile away at East Thetford and continued headed north, up the river. Where there had been millions of scouting bees at our farm, in a few minutes there were none.

The swarm eventually disappeared into far northwestern New Hampshire, where they were believed to have taken up residence in the stacked-up wrecked automobiles in a large junkyard abandoned years before, and then, finally, in spectacular Franconia Notch.

Little by little, one of those companies that catches and ships bees were able to capture many of the insects and transport them to areas of the U.S. that suffered from a deadly fungus that still endangers bee populations today.

Where the bees came from in such large numbers and why they took flight has never really been determined.

‘A Wintry Mix’

“Would you like to swing on a star?” (collage), by Rich Fedorchak, of Thetford, Vt., in the show “Wintry Mix’,’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., Nov. 19-Dec. 30.

The gallery says: "The holiday exhibition will feature the work of member artists from Vermont and New Hampshire. Works in a variety of media—oil, watercolor, drawing, printmaking, mixed media, photography, ceramics, textiles, sculpture, jewelry, and glasswork—will be on display and available for sale in a wide range of prices."

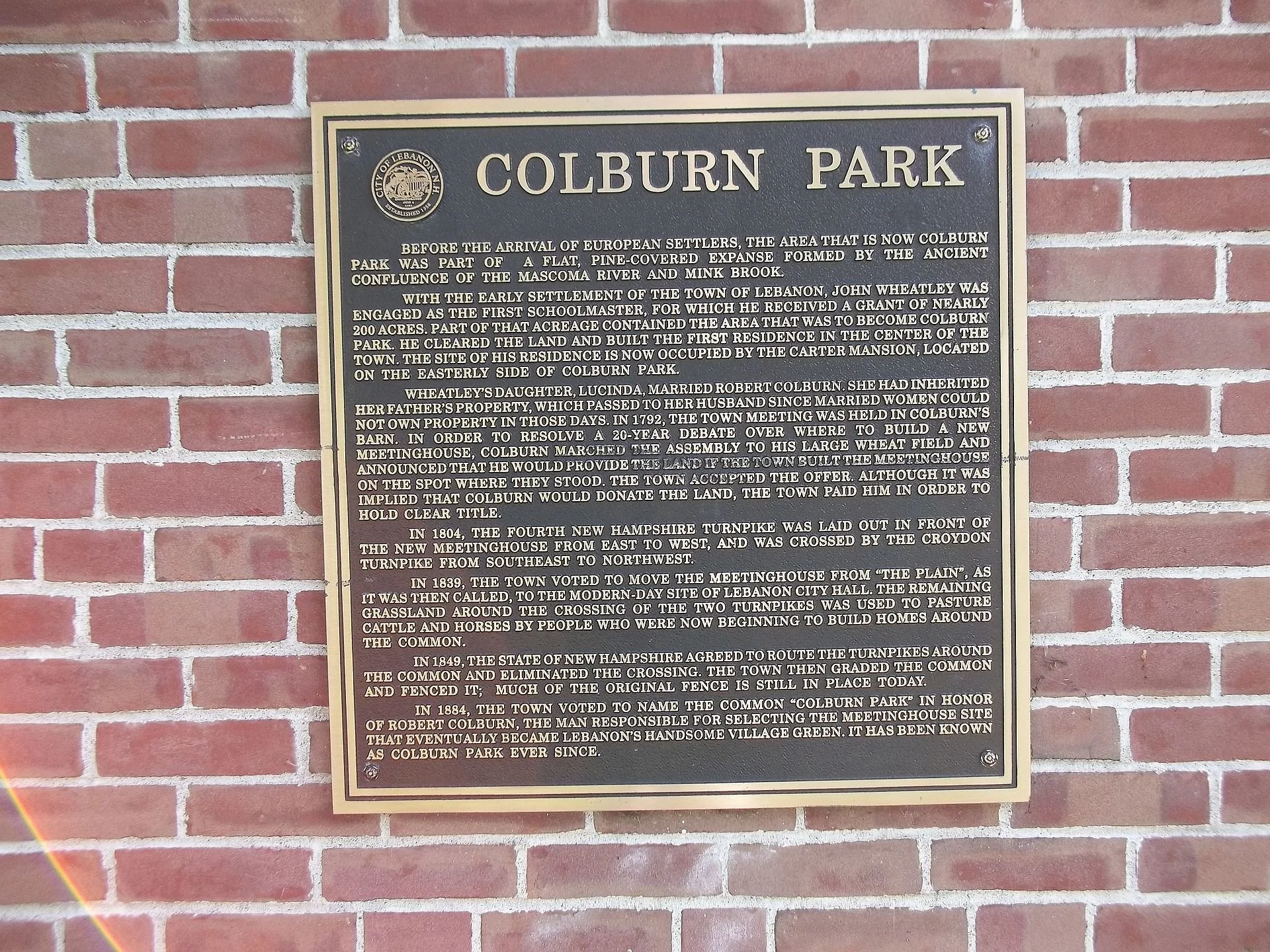

A little local history

— Photo by Artaxerxes

External and internal landscapes

“Connecticut River Valley at Claremont, N.H.,’’ by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902)

Along the Connecticut: Riverbank reconstruction project in Fairlee, Vt.

“There are few things as involuntary as a person’s identification with a landscape.’’

— Terry Osborne, writer and teacher, in his book Sightlines: The View of a Valley Through the Voice of Depression. He died of cancer in 2020 at the age of 60.

From the official summary of the book:

“For twelve years, writer Terry Osborne devoted himself to an intense exploration of the physical environment near his home in the {Upper} Connecticut River Valley {where he lived first in Thetford, Vt., and then in Etna, N.H.} The more he walked the land, the more deeply he came to know its hills and wetlands. But his growing intimacy with the area inspired something unexpected. The valley, formed by colliding and dividing continents, scoured by massive glaciers, and cut by rivers and streams, began to reveal and resonate with Osborne's internal landscape, long shaped from within by an unyielding depressive voice.’’

Two tough New Yorkers transplanted to Vermont

Fall foliage at Lake Willoughby, in northern Vermont

“I was happy, but am now in possession of knowledge that this is wrong. Happiness isn’t so bad for a woman. She gets fatter, she gets older, she could lie down, nuzzling a regiment of men and little kids, she could just die of the pleasure. But men are different, they have to own money, or they have to be famous, or everybody on the block has to look up to them from the cellar stairs.’’

Grace Paley (1922-2007), American writer and teacher and native of the Bronx, in An Interest in Life. In later life, she lived in Thetford, Vt.

“If the environment were a bank, it would have been saved by now.’’

Bernie Sanders (born 1941), a native of Brooklyn who’s now a U.S. senator from Vermont (which has some of the strongest environmental protections in the country). He’s a former mayor Burlington.

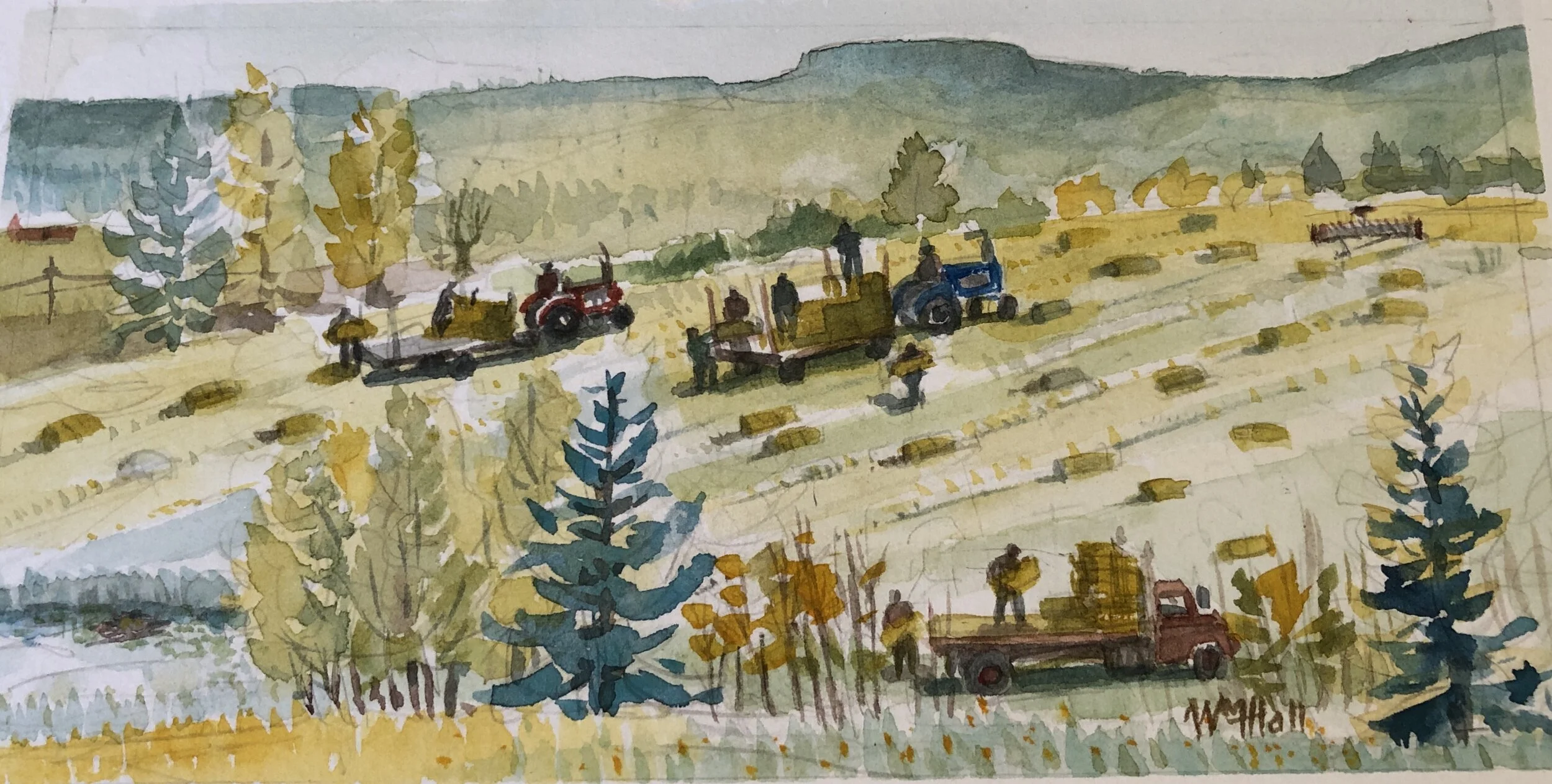

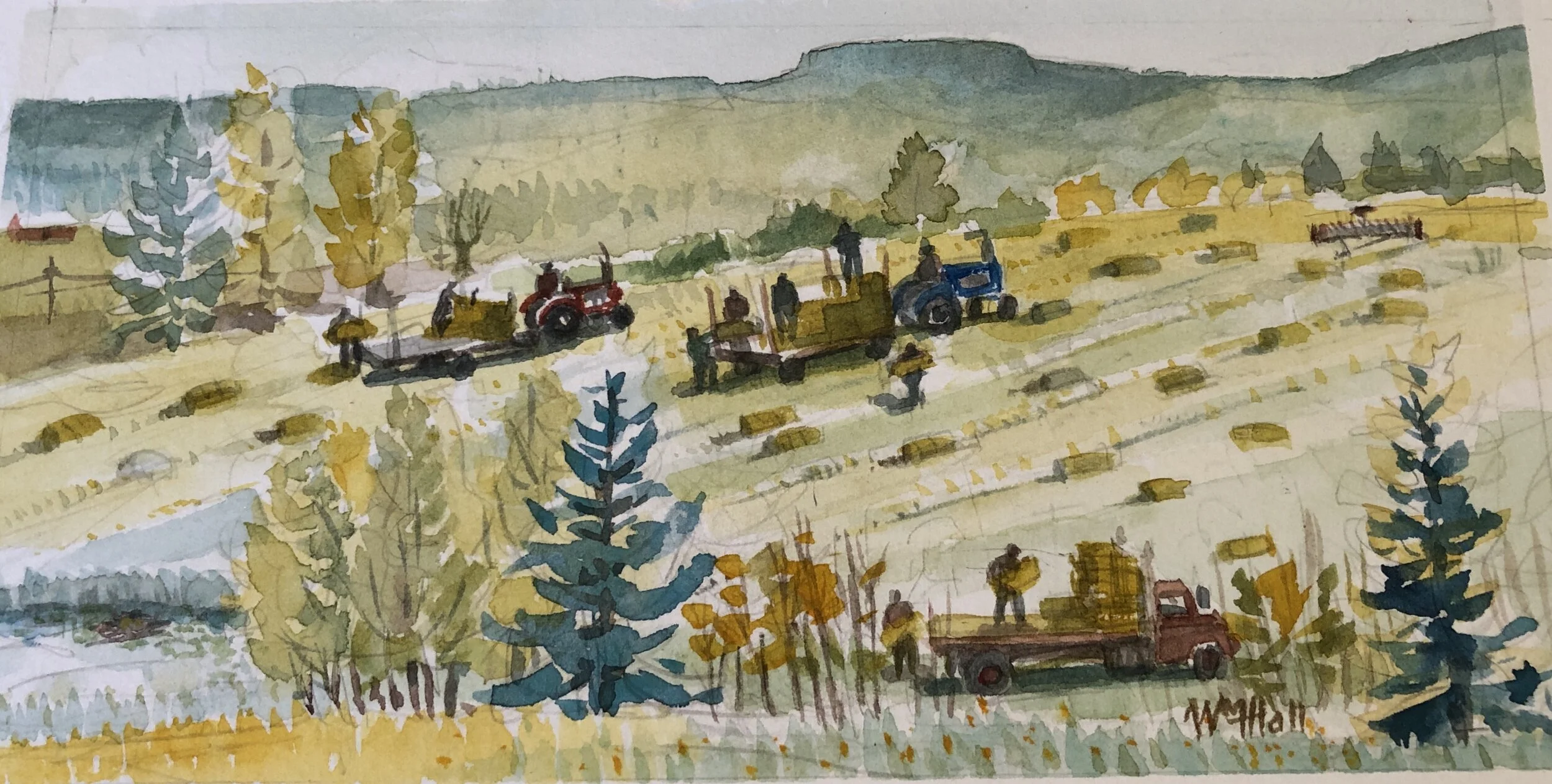

Bill Hall: The big gamble of 'early haying' in Vermont

“Harvesting the Hay Crop on Deadline’’

— Watercolor by Bill Hall

In late May it could get hot in Vermont’s Connecticut River “Upper Valley’’. You shifted slowly from here to there, but you had to move. If you didn’t you’d swear you would suffocate. You weren’t avoiding the oppressive heat as much as you were looking for some air to breath. Shade didn’t help much; it only served to dull the searing brightness. The heat was just there. If you were a farmer you had to get used to it, and get things done anyway. One of those things might have been to get in the early (season’s first) crop of hay: “early hay”.

In that sudden sweltering heat, you had to decide:

“Hay or no hay”?

Once you decided to hay, you had to do it fast. After the brutality of winter and the torrents of “mud season,” after the financial reality of dairy farming sank in once again, you had to get moving. You might put off the question of buying new equipment by fixing the old. Or should you pay down your loan?

Farmers in the Connecticut River Valley had to weigh the costs and rewards of throwing the dice once again. Would they risk an early haying or would they fold and walk away? That was the big gamble.

Early hay or “spring mow” sounds simple enough to a non-farmer. The common question asked, “Is it possible?” The correct answer is, “No, in most cases,” due to weather, which is always uncertain in northern New England. “Then, is it necessary,” you might ask?

In some professions, such as insurance, determining possibilities is a scientific matter, but in farming it’s just called “gambling”. My street-smart father called it “ The Farmers’ Hat-Trick”. He explained it to my brother and me as he shifted three dried butternut half-shells around on the kitchen table in short quick movements, one shell concealing a dried pea seed. You know this game. Which shell hides the pea? This was to demonstrate how, by a game he called “slight-of-hand,” farmers plotted to sneak a full barn of early hay right out from under the nose of a vengeful God.

My brother and I did not realize we were also getting a lesson about my father’s religious beliefs, seasoned by his ironic sense of humor. He was a traveling farm-equipment salesman who served a big territory. He understood farming, but elected to travel in a wider circle of go-getter types. He was also kind and sympathetic. By the end of the lesson he had impressed upon us how daring farmers were for trying to beat the heavy odds against succeeding at a harvest of early hay while it was still mud season. Dad called a career that required dealing with weather “a fool’s guess”. We also learned why we were lucky to be able to watch and understand this unfolding lesson where we could see it, in our own pastures. But we were safe from the financial challenges. My father traded the hay to our neighbors, the Vaughans, just to get our fields hayed, addressing the need to keep out brambles and weeds that cows shouldn’t eat, and to provide us with enough hay for our modest needs, which were for bedding, fodder and scratch hay for my grandfather’s turkeys and chickens (and their eggs)

Quirky local weather is king

Vermont has many microclimates, in part because of its geological history. Small farmers work every inch of that glorious land from the highest pastures of the Green Mountains to the floor of the Connecticut River Valley. Our 50-acre farm lay like a door-mat on the fertile plain of that valley, but the rush to harvest an early hay, or the decision not to attempt it, was happening everywhere in our little state, and all at once.

We would get news from Father’s weekly travels about the haying elsewhere. “They’re still not mowing in the Champlain Valley” maybe he’d report. He had seen bales in a high pasture over in the Vershire Hills, just west of us, but they were covered with snow and so on. Our total focus was on our two flat 25-acre fields, one on each side of our farm house. We knew from the farm kids at school that other farmers were ramping up to mow, rake, flip, dry and bale new hay everywhere around us, as soon as the weather permitted.

My father joked that if God controlled the weather then he was the one who needed to be appeased, fooled, dazzled or distracted. “He can be a practical joker at times,” he said, winking. The question was, if a farmer was going to sneak in such a neat stunt as an early hay harvest shouldn’t the farmer be very careful? If God knew, might he put obstacles in the farmers’ way? As our minister said, “To test him, to test his devotion”? It seemed like there was a, “side bet” between our dad and “Our Father”.

The tension was growing.

It was pre-spring. The days alternated between snow and mud. Most farmers were gun-shy and dazed by the deep dark winter they had just endured. Already skeptical about the benevolence of their God, a farmer could get discouraged from being house-bound and barricaded in their dark barns all winter dealing with rodents, frozen pipes and coughing cows. When the farmers returned to their kitchens, wives were waiting with “payable notices” illustrating the folly of a farming life. They felt vulnerable. The prospect of an early haying seemed further away than ever, but then it did every year.

Mud season was next. It held hands with winter. Those two soulless bullies worked together to test farmers’ resolve. Farmers felt helpless in their grip, and the sun seemed in cahoots with those darker elements of life because it offered only a few short winks in early May. “Was this spring”, they asked? It sleeted in April and froze tight every night for days sometimes, and maybe served up a blizzard for breakfast. Levity and faith were long gone by the time that the spring mud started to shift consistency from stinking brown glue in the barnyard to something more solid. But the fields were still soaking wet.

Wet fields? Were they the death warrant for early hay crops? A wet field normally meant one inaccessible to heavy farm equipment, and therefore useless until dry, but with a little luck and intense sunshine the ground might give rise to the green gold of the grass seeds within. If they could just get enough sunshine those seeds would explode to become a free bonanza of green early hay, but only in a field dry enough to work in. A windfall crop of sweet green hay would feed a farmer’s cows until the second haying season, in July, and would ensure that no hay need be purchased in the upcoming calendar year.

In Vermont the “early hay’’ was originally called “early mow’’. It was not baled. Teams of as few as two and sometimes as many as six work horses or mules hauled a man around who worked with horses, a “teamster,” upon a wood-frame contraption that combined pre- and post-industrial wood and metal embellishments. The wooden frame was as elegant as any stage coach and the iron parts included shiny as well as rusty parts, such as shearing bars, worm gears and iron seats.

The early mowers worked mechanically like a thousand men with sickles to lay the new grass low. Horse-drawn mechanical flippers or men with wooden rakes turned the grass over, on the same day it was mowed. This, done properly, dried out the hay enough to be “put-away”. Horse-drawn wagons were filled to the tops with loosely piled hay, which was lifted up using mechanical pulleys to be placed drooping over drying beams in the tops of barns, where the hay’s sweet perfume cleansed the stale air from the winter just passed. It was said such a barn was made “happy” by new hay. Cows’ eyes bulged upward as they bellowed in the milking level below as if trying to see through the floor above to the new hay they longed for.

This horse-powered equipment provided an advantage in its day. It could be operated in soaked fields before mud season had subsided, allowing access to wet fields without damaging them, as the weight of modern tractors, balers and trucks would have. Waiting for the proper surface conditions in those fields is what made the modern early hay process such a crap shoot .

Hay could be harvested when it was ready without farmers having to wait for equipment and manpower to converge on a field en masse. It could be gradually harvested more times during the season as it grew. The process was more controllable and flexible.

Above all it was a soulful process for both man and beast. There are still a few Vermont farmers who maintain horse and mule teams and the revered equipment that goes with farms with horses. Admiring them are amateur teamsters, purists, history buffs and people who still prefer the music of men’s voices coaxing animals forward to the sound of diesel tractors and metal balers. In some areas, drivers still park their cars along dirt roads in silent observance of this sacred event. But farming with horses has come to be seen as too slow and out of step with the times.

For the modern farmer and his quest for that early hay, he could only hope that his organizational skills and gambling spirit would see him through. These days, there are detailed weather predictions, radar and and satellite maps to show the regional picture, but it’s his personal experience and knowledge of his region that best tell him when to cut his hay. In our case in Thetford everything was temporary and nothing was as it seemed. It’s complicated. It tests your commitment. It leads you on. It dares you.

Is there enough time?

The fog over the valley floor and the heavy moisture it brings almost every day will dissipate by 9 a.m. if the sun is shining. Then will come a breeze. The heat of the sun on the valley floor will cause up-drafts, which will flow west through the hills of Vermont or east toward the hills on the New Hampshire side. In between is some of the most fertile soil in New England. The question is, can you wait for the sun to do its work and can you commit manpower and other resources enough to get the job done in time? If the farmer has his own hay-processing equipment, no matter how advanced, from cutting to storage, he’s in a stronger position; no one can let him down if he does it himself.

When it came to our two fields we aced it, but it was close. When the weather report said “no way” we had it hayed anyway. The Vaughan family, our aforementioned neighbors, made it happen. They arrived en masse when they saw that the rain that had been predicted for that morning did not fall. Sunny skies were forecast. The Vaughans made a commitment to cut both of our fields that day. They’d flip and rake them alternately and move from one field to another with Big-Red, the baler. We could see that there was still standing water near the fire pond (a source of water to put out barn fires) behind the barn. That area would be dry by midsummer and would have to wait.

The intense ‘baling day’

The Vaughans used two cutting tractors to get the hay down fast; both were working simultaneously. The flipper and rake alternated between the two fields.

Then came “baling day”. One year, the sky was overcast and the forecast was for rain by noon. As we had to wait for the morning dew to dry off, we were worried, but committed. The Vaughan family patriarch was unconcerned. Robert Vaughan Sr., who looked like someone in a Vermeer painting, decided that the hay would get baled and then stacked in his big barn by the end of that day, and that was that. Even if some of the last bales got a little wet, “We’re doing it”.

Just in case, he directed a couple of his five sons to go to the Vaughans’ barn and set up drying racks, where they’d be exposed to wind from the two enormous fans they had just installed. These fans were six feet wide and made the ends of the barn resemble an aircraft-test wind tunnel. This flow would ensure that our hay would retain its dryness in case the rain fell on the last day before we got the hay stacked. Mr. Vaughan wanted the new hay treated gingerly because it had a high alfalfa content and a limited tolerance to too much jostling.

Unlike with August haying, the alfalfa would stay in this new hay. When dry that early alfalfa would resemble flaked butterfly wings and if handled roughly would flutter down from the bottoms of the bales. This essence of the “first cut” must be maintained, otherwise why bother? Dryness was dicey for other reasons. The “good moisture” content was tricky to maintain, and “bad or deep moisture” would cause rot that would spread to hay around it.

Every bale in that bountiful harvest was loaded and trucked to the barn. The last three truckloads were stacked with the help of headlights of the other trucks and tractor. If we were lucky, the rain that might have been predicted held off until the last truck was mostly filled. A large tarp was fixed over the top and flapped wildly as we drove to the barn, where it was unloaded in the big alley in the center. Everyone helped and so it took only a few minutes. Then the big fans were turned on for the night. The sound that followed the throwing of the main switch gave the event a science-fiction feel. The fans chilled us as the breeze dried our sweaty, itchy backs. We would all seek relief lying in front of those fans in the sweltering days to come.

My brother and I always remember those times when the early hay was brought in.

Bill Hall is an artist based in Florida and Rhode Island. Hit this link.

Thetford, Vt. in 1912

— Photo by Mike Kirby

'Trying to become the forest'

Thetford, Vt., in 1912. Note the beautiful elm trees, now long gone.

"This hill

crossed with broken pines and maples

lumpy with the burial mounds of

uprooted hemlocks (hurricane

of ’38) out of their

rotting hearts generations rise

trying once more to become

the forest....''

From "A Walk in March,'' by Grace Paley (1922-2007), the famed short-story writer. A native New Yorker, she moved to Thetford, Vt., in later life, where her second husband had a farmhouse. Thetford is a beautiful town on the Connecticut River, whose very fertile bottomlands still sustain some prosperous farmers. The town has drawn many celebrities to buy property there, in part because of the proximity of Dartmouth College, which is a few miles south on the New Hampshire side of the river.