Thomas C. Jorling: How to use the highway system, new building codes to address climate change

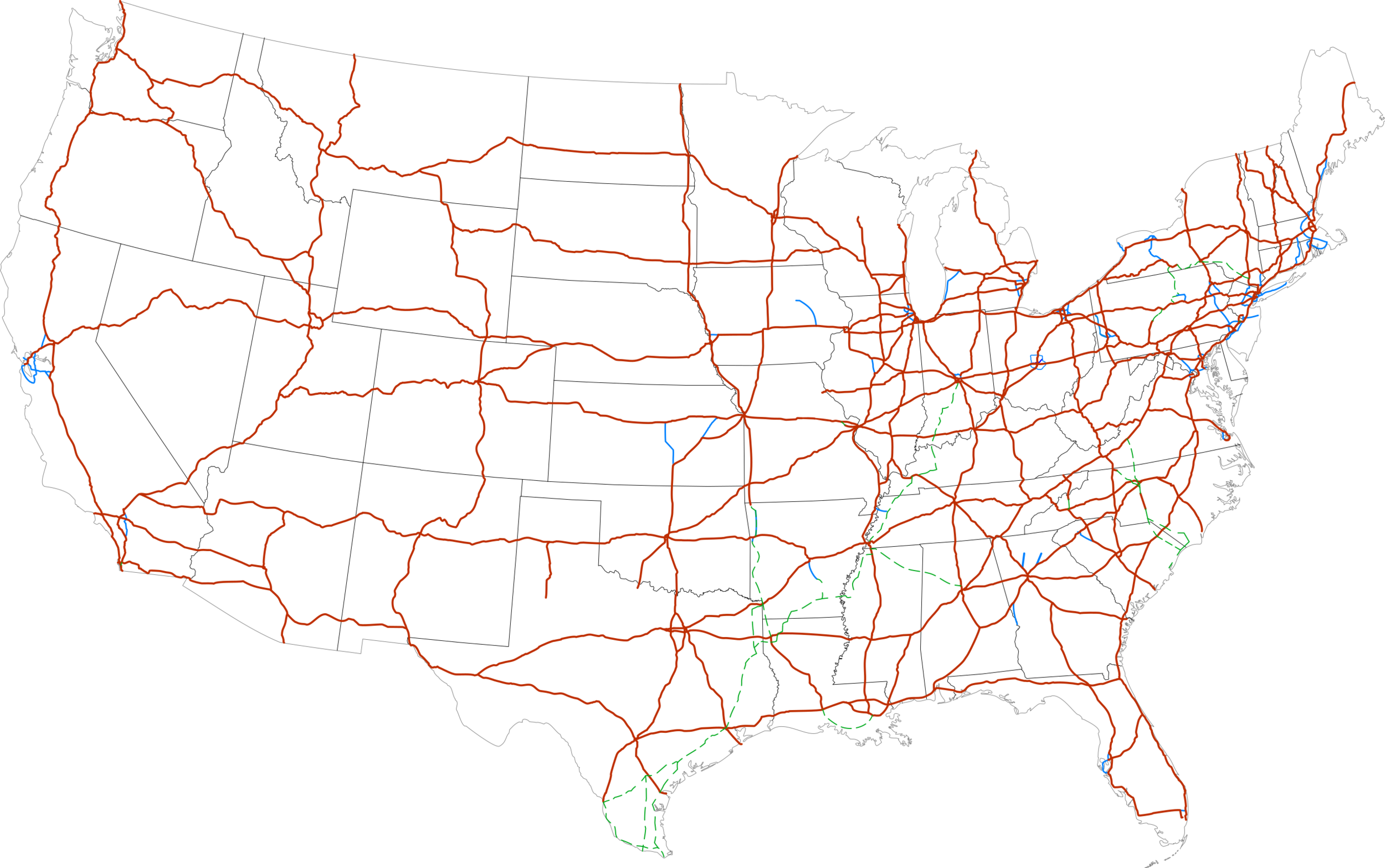

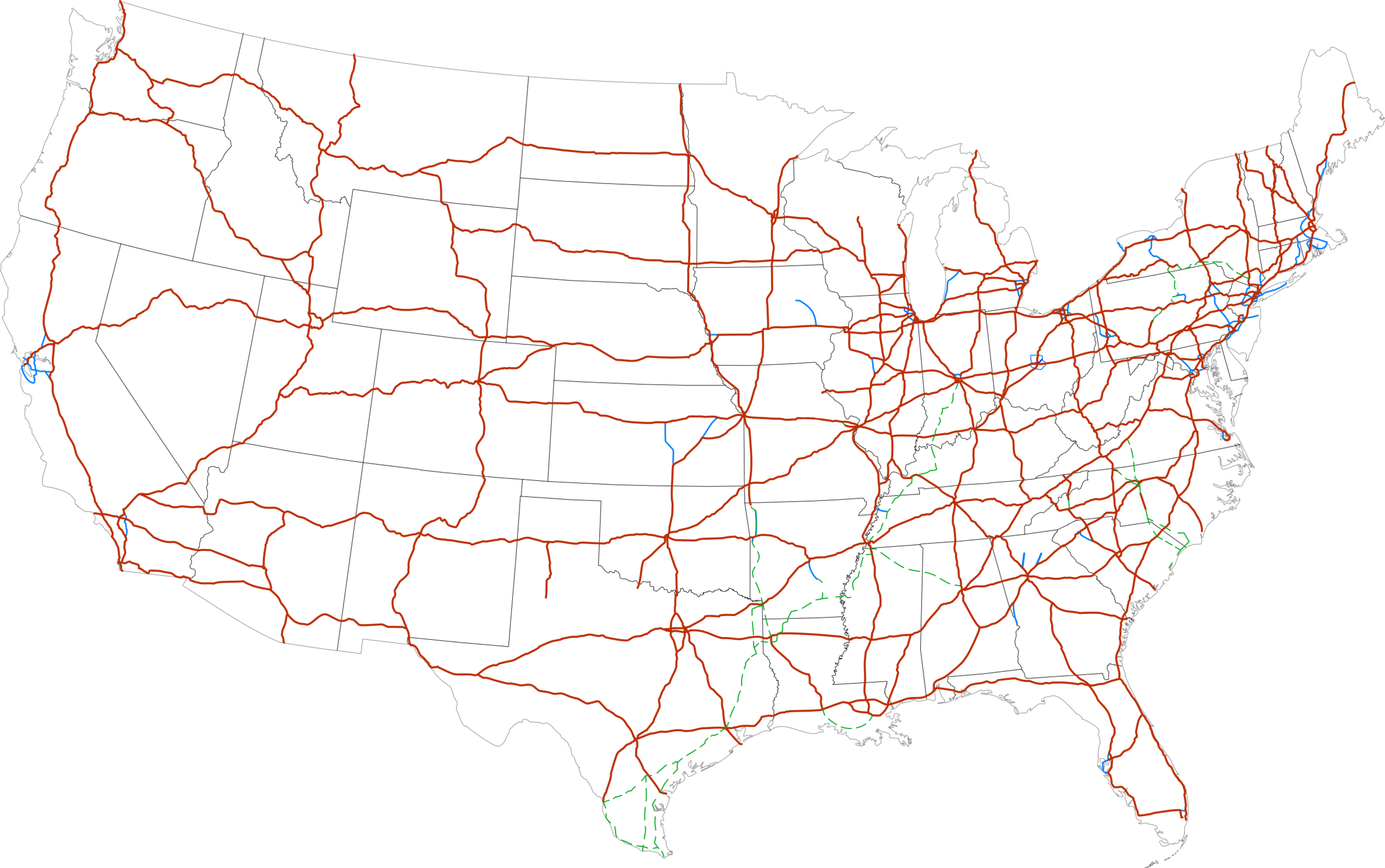

Map of the current Interstate Highway System in the 48 contiguous states

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Climate change is real and accelerating. It requires an urgent response that focuses all the strategies and tactics necessary to stabilize the Earth’s temperature regime.

The objective to guide research, development and implementation is straightforward: Achieve an all-electric economy. Simply put, all sectors of energy use—agriculture, transportation, industrial, residential, business, etc.—must transition to electricity. Where liquid fuels are necessary, such as aviation, they must be produced from biological processes.

This objective, however, can be satisfied only by transforming electricity generation to alternative—non-combustion—sources that convert into electricity the energy from the inexhaustible clean supply provided by the sun and ecosystem, primarily wind and solar.

As the transition occurs, existing fossil-fuel energy will be replaced and future growth will be accommodated. It is a transition that has historical examples and precedents: wood to coal, oil and gas; horses to automobiles; hard lines to cell phones, among many other examples of progress. Dislocations associated with these transitions have occurred, but they were quickly overcome by innovation and adaption. This has been the story of human progress.

While some elements of the transition require intervention at the national level such as the Clean Air Act addressing health-damaging air pollution, the need now is for federal and state legislation and policy to discipline and make fair the transition from coal, oil and gas.

Needed: A smart grid

There is no question the nation needs a “smart grid” to facilitate the delivery of alternatively generated electricity across geography and time zones. This raises the question: Can such a grid be created without defiling the countryside and disrupting ecosystems? The answer is yes.

A significant portion of the cost of the Interstate Highway System was incurred securing rights-of-way. As a transportation system, it has been highly successful. One consequence, which is greatly unappreciated, is that these rights-of-way represent a tremendously valuable federal and state asset that shouldn’t be limited to concrete and asphalt.

Even a quick look at a national map of the Interstate Highway System reveals a network connecting rural America and urban America. The highway network can also be a connection between and among the same areas for electricity generation, management and distribution. Buried, reinforced conduit along the rights-of-way of the system can connect—and make smart—the grid, enabling electricity to be moved and delivered efficiently and effectively. This will allow electricity, from generation to user, to be managed back and forth across the country as needed in response to changing seasons, weather and time of day.

More than transportation

We need to change these rights-of-way from single-use to multiple-use. This network, already invested in by the public, can accommodate not only an electric grid, but also pipelines and even elevated high-speed rail. Letting the asset represented by this extensive right-of-way network be underutilized is a travesty. It can and should be used for multiple national needs. All of which can help address climate change.

The development of a multiuse right-of-way based on the Interstate Highway System to accommodate a smart electrical grid, expansion of broadband and other networks presents opportunities and challenges for higher education. Among opportunities, use of the highway network can enable rapid expansion and availability of broadband, not just to institutions but to communities all across the country. This would enable all citizens, families and communities to benefit from full access to the internet and overcome the disparities of access to make higher education more available to everyone. Among challenges, using the Interstate Highway System as a multiuse asset will require the innovation of higher-education institutions (HEIs). Ways to stimulate that innovation could include, for instance, a competition among HEIs, especially those with technically oriented capability, to design easily and rapidly installed, low-cost conduit structures on or in the ground for the electric grid on the interstate highway network. HEIs should become centers of innovation and excitement for the societal transformations that are going to occur as the U.S., indeed the world, addresses the challenges of climate change and the sustainability of communities and infrastructure in the quest for a better future.

We do not need to establish new rights of way across the American landscape taking any more forest or agricultural land that plays so important a role in capturing and storing carbon in wood, fiber and soil.

Another grossly underutilized resource is the extensive areas of roofs on structures, especially flat-roofed structures and the parking areas adjacent to the structures, that now cover extensive areas of our landscape. Before human settlement and the expansion of built-up land, these areas captured the energy of the sun in what ecologists call primary productivity: that is, plant photosynthesis converting sunlight into biomass in complex ecosystems. These areas can once again be used to capture the sun’s energy and convert it to electricity.

To this end, the country needs to adopt national building codes to require:

New building structures to be physically oriented and designed, to the extent possible, for maximum use of sunlight, both passive and through photovoltaic systems.

Every flat-roofed structure newly constructed that has a surface area greater than half an acre should be required to install rooftop solar photovoltaic panels.

All current flat-roofed structures greater than an acre should be required to retrofit the roof with solar panels within five years. Creative partnerships between owners, utilities and solar investors and installers could flourish in this effort.

All parking lots greater than an acre should be required to install elevated solar panels. This can be done by the parking lot owner or leased for a nominal or no charge to a solar panel installer.

All forms of federal assistance (such as loans, guarantees, grants or tax benefits) for housing and economic development, should be conditioned on financially support measures to achieve energy efficiency and install solar electric-generation opportunities.

These achievable, cost-effective steps can result in the production of large amounts of electricity and contribute significantly to achieving an economy without fossil fuels. These widely distributed systems, connected through a smart grid, in protected conduits (rather than vulnerable suspended wire systems), could assist in making our economy sustainable and the people supported by resilient and reliable electric power.

Thomas C. Jorling is the former commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and former director of the Center for Environmental Studies at Williams College among other key posts.

The average insolation in Massachusetts is about 4 sun hours per day, and ranges from less than 2 in the winter to over 5 in the summer.

Charles Desmond/Thomas C. Jorling/Kier Wachterhauser: How Harvard and other rich institutions can help save our planet

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Nonprofit institutions with large endowments have been facing challenges from various stakeholders contesting the management of their investment portfolios. While these challenges are most commonly associated with institutions of higher education, pension funds and private foundations will increasingly face similar challenges regarding how the management of their endowments affects socially important policies. Together, these endowments represent hundreds of billions of dollars, and the market power they possess is very substantial.

In the case of higher education, students, faculty and some alumni are pressing these institutions to divest of their holdings in fossil fuel-based companies. These include coal, petroleum and, in some cases, natural gas companies. This advocacy is based upon an overall societal objective to decarbonize our energy system in order to hold greenhouse gas emissions at levels believed to be necessary to prevent an increase in global temperatures above 1.5°C. For above this level, there is widespread consensus in the scientific community that the climate will change in ways that will threaten the ability of the life-supporting biosphere to sustain the human population, which that will grow to something on the order of 10 billion by 2050. The threats from climate change are wide-ranging, from droughts and extreme storms to sea level rise and ocean acidification to migration of infectious diseases and rapid species extinction.

The challenge of climate change is real and the nonprofit institutions that manage vast portfolios must examine how their substantial investments affect the social, economic and environmental well-being of the human community. Simply put, the trustees of these major nonprofit endowments must examine the contribution to human well-being they make with the explicit choices in the composition of their portfolios.

Certainly divesting in carbon-based corporations is one avenue to consider. It is, however, our proposal that a positive investment strategy is a much more effective way to drive the message that climate change is real and requires action by nonprofit organizations who sit on large amounts of capital.

Thus, we propose, as a start, that nonprofit organizations with endowments greater than $1 billion commit to investing 10% of their endowment in corporations whose primary business activity is building and operating alternative energy systems based upon the endless supply of the sun’s energy and the wind. These alternative energy systems would include photovoltaic electric generation and associated energy storage technology, especially batteries.

The power of this investment strategy is immense. Consider the impact of a 10% investment from 100 institutions with endowments greater than a billion. At a minimum, this would produce $10 billion. Harvard alone would produce more than $4 billion. Investments of this scale would take this nation a long way toward decarbonization. More specifically, these investments would replace fossil fuel generation of electricity with the concomitant result that portfolio managers would cease to make any investments in fossil fuel companies. Thus, the proposed strategy would also accomplish the objectives of divestment.

And these investments are competitive. Investments in wind and solar projects are now returning 6% to 10%, which is fully in line with the range of investment objectives that trustees of nonprofits instruct portfolio managers to achieve.

Climate change represents a serious threat to the well-being of the human community. Leaders of nonprofit organizations cannot in good conscience watch this threat unfold as if it is someone else’s responsibility. It is also our hope that the managers of nonprofit funds in this country will set the example for all to follow, regardless of industry. It is the responsibility of all of us.

If you are managing massive amounts of capital and can achieve competitive rates of return by investing in alternative energy technologies that will help protect the life-supporting biosphere, the choice appears clear: Act Now!

Charles Desmond is CEO of Inversant, the largest parent-centered children’s saving account initiative in Massachusetts. He is past chair of the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education and was a higher education policy adviser to former Gov. Deval Patrick. Since 2011, he has served as a NEBHE senior fellow. Thomas C. Jorling is former CEO of the ecosystem nonprofit NEON Inc., former VP for Environmental Affairs at International Paper Co., former commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, and former professor and director of the Center for Environmental Studies at Williams College. Kier Wachterhauser is a partner at the law firm of Murphy, Hesse, Toomey & Lehane, LLP, in Quincy, Mass., where he specializes in labor and employment law, legal compliance and governance, and litigation.