Felice Duffy: Forward or backward with new Title IX regs?

— Photo by Sichow

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

NEW HAVEN, Conn.

On the 50th anniversary of the enactment of Title IX, the U.S. Department of Education released proposed new regulations for Title IX policies. For the most part, these new regulations reverse regulatory changes made during the Trump administration.

The Biden administration insists the new regs will “restore crucial protections” that had been “weakened.” Commenters have their own opinion on the efficacy of the proposed regulations, with over 235,000 formal comments filed during the 60-day comment period.

So, do the proposed regulations represent a step forward or backward?

Overview of changes

The deceptively simple words in Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 have been augmented by numerous regulations and judicial interpretations over the decades. While the aim is to protect students from sex-based discrimination, many worry that the regulatory efforts to right or prevent wrongs go too far and infringe on the due process rights of those accused of Title IX violations.

During the Trump administration, the Office for Civil Rights spent nearly 18 months reviewing less than 125,000 public comments before issuing new final regulations that resulted in significant changes. With almost 90% more comments to review this time around, it will be interesting to see how long it takes the department to issue final rules about key issues they are considering, such as:

How colleges are required to investigate reports of sexual assault.

Whether colleges are required to hold live hearings before issuing decisions.

Protections for LGBTQIA+ students.

The definition of sexual harassment.

While some commenters object that the proposed rule changes go too far in one direction, others insist they do not go far enough.

Live hearings and cross-examination

One of the most significant controversies regarding the proposed regulations centers on the types of proceedings colleges must hold to hear Title IX complaints. The new regulations allow schools to hold separate private meetings with complainants and respondents instead of live hearings with the opportunity for cross-examinations. Supporters of the change assert that the disciplinary hearings required under current rules are too much like adversarial courtroom proceedings. Many say that allowing colleges to establish less formal, non-confrontational processes will save money and encourage victims to proceed without fear of repercussions.

However, other commenters expressed concerns that eliminating live hearings and allowing colleges to use the same body to investigate and judge the validity of complaints violates the due process rights of students accused of violations.

Burden of proof in sex discrimination and misconduct

Controversy continues about how much a complainant must prove to win a case alleging that they have been subjected to sexual discrimination, harassment or assault. The proposed rules would generally establish a “preponderance of evidence” standard in most but not all cases, so a student need only to prove that it was “more likely than not” that the discrimination occurred. The current rules provide a choice between the preponderance of evidence and clear and convincing evidence standards.

Critics of the change say the clear and convincing standard is necessary to protect the respondent’s rights, and they point out that it is still less than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal cases.

Gender identity and sexual orientation

The proposed regulations expand the anti-discrimination protections of Title IX to include gender identity and sexual orientation when it comes to college programs or activities, except athletics. The department has delayed ruling on the highly controversial issues related to participation in sports programs.

Even without addressing athletics, the expansion of protections generated numerous forceful comments. Those in favor assert that the new rules will improve the safety and wellbeing of LGBTQIA+ students and resolve equality issues that are currently being addressed on a costly case-by-case basis in the courts. Opponents of the expansion allege that by requiring schools to allow participation in programs based on gender identity, the new regulations actually violate the Title IX mission of providing equal access to education benefits on the basis of sex. They also argue that the proposed changes exceed the department’s statutory authority and would chill free speech rights on campus. For example, the definition of sexual harassment will be expanded such that students could be investigated for not using certain pronouns or using incorrect pronouns that do not correctly reflect the gender with which a person identifies.

Are we moving forward or backward?

While the new regulations are not yet final, the final regs are expected to track closely with the proposed version. Whether you are a complainant or a respondent regarding any number of explicit proposed provisions in the regulations, each side would argue the provision is either moving toward a brighter future or repressive past—any provision that makes it more difficult to file a complaint (such as requiring a formal complaint under the current regs) makes it harder for complainants (repressive past) and easier for respondents (brighter future); and keeping the standard at the preponderance of evidence versus raising it to clear and convincing, is easier for complainants (repressive past) and more difficult for respondents (brighter future).

The one certainty is that when schools implement the new regulations, those who are unhappy with the results will turn to the courts for clarification and possible nullification. It will be interesting to see how the courts respond.

Felice Duffy is a Title IX lawyer with Duffy Law, based in New Haven, Conn., and a former federal prosecutor.

Thomas A. Barnico: Should Feds dictate rules on campus sexual misconduct? Beware

“My Eyes Clear Away Clouds” (collage), by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Department of Education is poised to reverse Trump-era rules governing claims of sexual misconduct on campus. One could forgive weary college counsel for a case of vertigo: The Trump rules themselves reversed the Obama rules, and Biden’s 2021 nominee to enforce the rules—Catherine Lhamon—held the same office at the Education Department under Obama. In three years, the election of 2024 may bring yet another volte-face at the department. Even those who support the likely Biden changes may wonder: Is this any way to run a government?

As they ponder that question, frustrated counsel should note the primary source of the problem: the desire by serial federal officials to dictate hotly contested standards of student conduct for millions of students in thousands of colleges in a nation of 330 million people.

Some issues are better left to the provincials. As Duke Law professors Margaret Lemos and Ernest Young argue: “Federalism can mitigate the effects of [national] political polarization by offering alternative policymaking venues in which the hope of consensus politics is more plausible.” Delegation to state or local governments or, in education, to private actors, can “operate as an important safety valve in polarized times, lowering the temperature on contentious national policy debates.”

Of course, as Lemos and Young admit, “a federalism-based modus vivendi is unlikely to satisfy devoted partisans on one side or another of any divisive issue.” Such conflicts pit competing and compelling interests against one another.

In the Title IX context, parties fiercely debate the adequacy of protections for complainants and respondents alike: Does the respondent have a right to confront and cross-examine the complainant? Does the respondent have a right to counsel in their meeting with student affairs personnel? Do colleges and universities have to abide by a common definition of “consent” to intimacy in their student conduct manuals?

And, in polarized times, many will be unsatisfied with a patchwork of rules that apply state-by-state or college-by-college. Lost in this good-faith debate is the point that, even for issues with national effects, an oscillating national rule can cause more instability than an entrenched array of differing local rules.

Noted diplomat and scholar George F. Kennan aptly described the problem in Round the Cragged Hill: “The greater a country is, and the more it attempts to solve great social problems from the center by sweeping legislative and judicial norms, the greater the number of inevitable harshnesses and injustices, and the less the intimacy between the rulers and ruled. … The tendency, in great countries, is to take recourse to sweeping solutions, applying across the board to all elements of the population.” Central dictates, Kennan said, often show “diminished sensitivity of … laws and regulations to the particular needs, traditional, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and the like, of individual localities and communities.”

Of course, changes in administrations often bring changes in policy. Elections matter, and victors arrive with fresh ideas and an appetite for change. This is a highly democratic impulse; as U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote: “A change in administration brought about by the people casting their votes is a perfectly reasonable basis for an executive agency’s reappraisal of the costs and benefits of it programs and regulations.”

Sometimes, such reappraisals will follow a reversal in the public current of the times. Where the new current runs strong and fast—and newly elected officials carry a decisive electoral mandate—a sweeping national solution may reflect a consensus view. But when electoral margins are slim, dangers lurk. When national executive and legislative power repeatedly changes hands by slim margins, policy changes may reflect not strong new currents but more of a series of quick, jolting bends.

The shifting procedural rights of the complainants and respondents in the Title IX misconduct hearings more resemble the latter. The abruptness of such changes grows when the commands flow not from a congressional act but by “executive order,” administrative “guidance,” or “Dear Colleague” letters that lack the procedural protections of a statute passed by both houses of Congress. Moreover, too-frequent changes in rules—whatever their procedural sources—have long been seen to create uncertainty, undermine compliance and lessen respect for law.

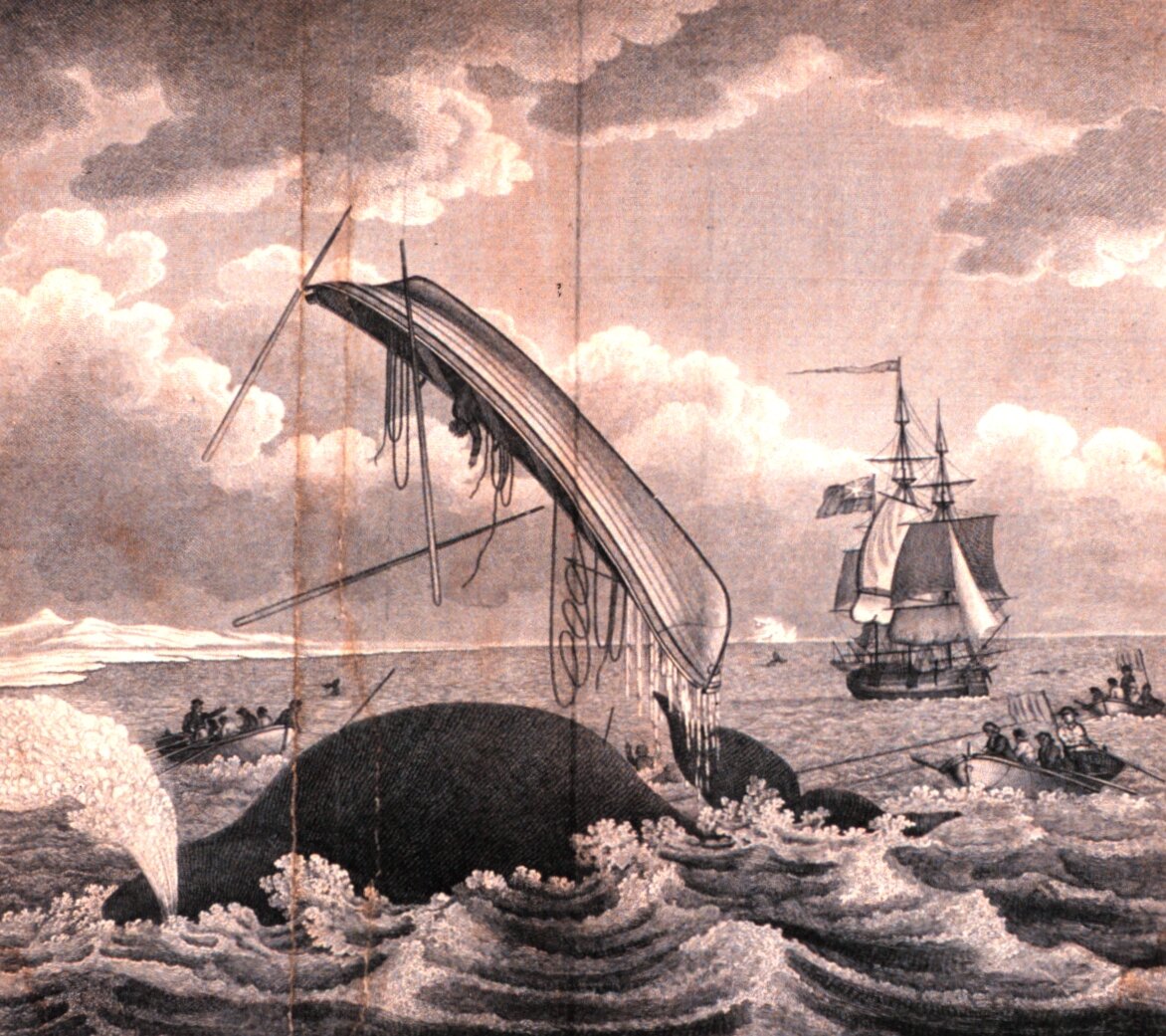

The options for beleaguered college counsel are few. Education Department rules apply to colleges because colleges desire federal funds. Few colleges wish to turn off the spout of the federal Leviathan. The masters they acquire are both the sovereign Leviathan of Hobbes and the whale dreamed by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick: a giant of the deep that pulls colleges to and fro, as if dragging them in a whaleboat on a “Nantucket Sleigh Ride.”

In our modern form of the tale, the whaleboat is the college, and the harpoon is its application for federal funding. The harpoon hits its rich federal target, but the prize brings conditions, represented by the attached rope. “Hemp only can kill me,” Ahab prophesizes. “The harpoon was darted; the stricken whale flew forward; with igniting velocity the line ran through the groove;—ran foul.” The rope—initially coiled neatly in a corner of the whaleboat—runs out smoothly until spent. Then it tangles, converting itself to a weapon more deadly than the harpoon. Bound by the rope—the conditions on federal funding—the college descends into the vortex.

Biden’s likely Title IX rules on student misconduct will pull college administrators to and fro again, whalers on a new, hard ride. The day that the federal government withdraws from the field seems distant; like Ahab, Education Department officials of both parties seem “on rails.” In the meantime, college counsel should brace for the latest chase and hope that they—like Ishmael—will live to tell the tale.

Thomas A. Barnico teaches at Boston College Law School. He is a former Massachusetts assistant attorney general (1981-2010).

“Nantucket Sleigh Ride”: Illustration of the dangers of the "whale fishery" in 1820. Note the taut ropes on the right, lines leading from the open boats to the harpooned animal.

Bret Murray: Possible Title IX changes could boost colleges' exposure, discourage victims from coming forward

Title IX played a major role in expanding women students’ team sports at co-ed institutions

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Title IX, the federal civil rights law passed in 1972, was a landmark piece of legislation that prohibited sexual discrimination in educational institutions across America. It reads, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Enforced by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR), Title IX has helped level the playing field by ensuring that students of all genders receive access to scholarships, funding, sports, academic coursework, and protection from sexual harassment, among other things.

But three recent lawsuits in which male students (John Does) who were accused of and disciplined for sexual misconduct argue that they were denied due process by their universities because of unfair Title IX policies. The men filing suits are from Michigan State, the University of California and California State. While the circumstances of the cases are different, the John Does essentially argue that Title IX policies were administered unfairly at their universities. The accused male students say they were denied their due-process rights, they weren’t allowed to cross-examine their accusers, and they were not given a live hearing before a neutral fact-finder.

Significantly, the plaintiffs in these cases are seeking to have their cases certified as class-action suits.

If any of these cases receive class-action status and prevail, it could reverse the outcomes of numerous sexual violence cases that were adjudicated on college campuses over the years. The effects could be far-reaching and present a host of problems for universities that have sanctioned students after conducting Title IX investigations of sexual-misconduct accusations. This could include any investigation by a college or university of sexual assault, harassment, exploitation, indecent exposure, relationship violence and stalking.

What is the impact of a class-action certification for colleges and universities not named in the suits?

First of all, disciplinary sanctions on students who were previously found guilty on sexual violence charges at these universities could be overturned. And that could open the doors to more lawsuits at more colleges and universities within their federal circuit court jurisdictions. Any John or Jane Doe who was expelled from a school after a sexual misconduct adjudication hearing would only need to prove that they were denied their due-process rights by not having the opportunity to cross-examine their accuser or other witnesses before a neutral fact-finder to make a prima facie case. Universities could face mounting legal defense fees, potential settlement payouts, as well as other costs like hiring outside public relations counsel.

Secondly, class-action status could force universities to change their processes for handling sexual violence cases going forward. Affected schools would have to allow cross-examining opportunities in front of neutral fact-finders and wouldn’t be able to use school adjudication officers as judges. For institutions not utilizing mediators or other third-parties as neutral fact-finders during their Title IX processes, additional funds will need to be budgeted in order to pay for these new expenses.

Lastly, should the cases be certified and rule in favor of the John Does, the courts will base their rationale on due-process fairness to all parties. But such a ruling could have the unintended consequence of discouraging victims from coming forward if they must be cross-examined by a representative of the alleged assailant during the hearing process. Affected colleges and universities will clearly need to incorporate the courts’ holdings into their Title IX policies and processes, but they need to do so in ways that will not discourage victims from reporting acts of sexual violence.

These cases could have implications when it comes to the exposure that colleges and universities face in their Title IX policies and investigations.

How can universities mitigate their exposure if the Title IX cases are certified as class-action suits? Educator Legal Liability (ELL), Directors & Officers Liability and Commercial General Liability insurance policies can offer a layer of protection for both the higher education institutions and their employees. In addition to covering legal defense costs, ELL coverage can assist with fines and potential settlements in these matters as well.

Schools might have an adequate existing insurance program, or they might have to amend their policies and program to ensure coverage for such risk exposures. As these and other similar cases play out, now is a good time for colleges and universities to proactively check in with their risk advisers and brokers.

Bret Murray is higher-education practice leader at Boston-based Risk Strategies.

Ariel Sullivan: Illegal procedure? Title IX and sexual assault

Via our friends at the New England Journal of Higher Education, part of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org) BOSTON Florida State University quarterback and Heisman Trophy winner Jameis Winston was recently cleared of sexual assault charges following the university’s two-day investigative hearing. The high-profile investigation was launched under Title IX, which requires schools to investigate such allegations even in the absence of criminal charges. Winston’s attorney immediately took to his Twitter account to share the news of the outcome—the finality of which is pending any appeal by the complainant—and provide the following emphasized excerpt from the hearing panel’s decision “In sum the preponderance of the evidence has not shown that you are responsible for any of the charged violations of [FSU’s Misconduct] Code.”

While most institutions do not face such intense public interest and ongoing media coverage of their Title IX investigations—typically reserved for cases involving Division I athletes—many are scrutinized by their campus community and the media for the way that they respond, or fail to respond, to allegations of sexual assault. Tack on the fact that nearly 100 colleges and universities are currently under investigation by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) for possible violations of Title IX, and the conclusion is clear: Colleges need to be better prepared to respond immediately and appropriately to complaints of student-on-student sexual violence in accordance with the law and their internal policies.

OCR attempted to provide guidance to help colleges comply with their Title IX obligations through a 45-page guidance document entitled “Questions and Answers on Title IX and Sexual Violence,” published on April 29, 2014. Since then, colleges have been scrambling to ensure compliance with this latest guidance and avoid becoming the subject of an OCR investigation. This one-sided approach leaves colleges vulnerable to claims of negligence and mistreatment by the accused, whose rights are barely recognized by OCR. Moreover, OCR’s guidance does not provide answers to the seemingly endless conundrums that arise in sexual violence cases, nor is it entirely consistent with other recently promulgated federal regulations. It is therefore of paramount importance that those in charge be capable of handling the competing interests that arise in responding to sexual violence complaints.

Best practices for college officials include:

- Be sensitive to the complainant’s emotions, needs and rights, while ensuring that the rights of the respondent are also met. One of the biggest risks colleges face in responding to sexual violence complaints is a subsequent claim or lawsuit by the complainant or the respondent. With regard to the complainant, such claims often stem from her perception that campus officials were not sensitive in the way that they spoke to the complainant throughout the process. OCR states that those in charge of responding to sexual violence complaints have training or experience working with and interviewing persons subjected to sexual violence, including the effects of trauma and associated neurobiological change, appropriate methods to communicate with students subjected to sexual violence, and cultural awareness regarding how sexual violence may impact students differently depending on their cultural backgrounds. By providing such training to those with responsibility for carrying out their Title IX procedures, colleges will help to ensure that appropriate sensitivity is employed in working with complainants. At the same time, they must ensure that their sensitivity toward the complainant does not infringe on the respondent’s right to a fair and impartial investigation, which is often the crux of subsequent claims brought by respondents.

- Employ interim measures to assist the complainant throughout the process, but ensure that the measures taken are reasonable and appropriate under the circumstances. For example, a complainant may ask the college to immediately suspend the respondent or bar the respondent from campus while the investigation is pending. Notably, such interim measures are not suggested in the OCR’s guidance. The practical approach is to employ such severe interim measures only in in the presence of aggravating factors such as the use of a weapon, threats of future violence, a group assault, or multiple claims against the same respondent.

- Be communicative and transparent about the complaint and the process, while remaining confidential and adhering to privacy laws. Like the sensitivity issue addressed above, subsequent claims arise from a perceived lack of communication regarding the process. Therefore, colleges should communicate with the complainant and respondent on a regular basis, and respond to their questions in an equal and impartial manner. At the same time, colleges should develop procedures for addressing concerns and inquiries from parents, students and the media related to Title IX investigations, in accordance with federal privacy laws and consistent with public relations objectives.

- Review and update Title IX policies in accordance with the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act (“VAWA"), despite OCR’s suggestion to the contrary. OCR’s guidance insists that VAWA has no effect on a school’s obligations under Title IX. However, the final VAWA regulations published on Oct. 20, 2014, and effective July 1, 2015, indicate otherwise. Indeed, with regard to the presence of an advisor, the new VAWA regulations require colleges to allow both parties to be accompanied to any proceedings “by the advisor of their choice,” while OCR’s guidance merely states that if the college allows one party to have an advisor at the proceedings, it must do so equally for both parties.

- Develop and implement a memorandum of understanding (“MOU”) with local law enforcement that will allow the college to meet its Title IX obligations to resolve complaints of sexual violence promptly and equitably. The MOU should delineate responsibilities for responding to and investigating incidents and reports of sexual violence on and off campus, as well procedures for sharing information about students and employees who are the victim of, a witness to, or an alleged perpetrator of an offense of sexual violence.

As colleges bear more responsibility and are subjected to greater scrutiny than ever before in carrying out their obligations under Title IX, it is more important than ever for those in charge to follow these and other best practices to guide them in responding immediately and appropriately to reports of student-on-student sexual violence.

Ariel Sullivan is a partner in the Massachusetts law firm Bowditch & Dewey. She concentrates her practice in all aspects of labor and employment law.