Sam Pizzigati: UAW victory’s global significance; next stop Tesla?

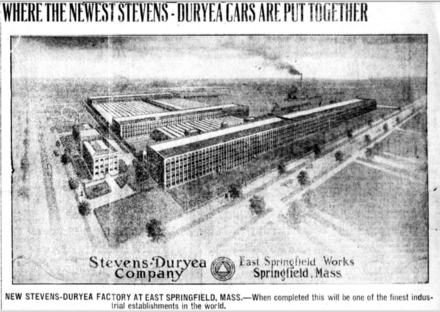

On Sept. 20, 1893, Charles and Frank Duryea of Springfield, Mass., built and then road-tested, in that city, the first American gasoline-powered car. During the early years of automobiles, several independent manufacturers built cars in the state. In 1900, Springfield gained Skene American Automobile Co. (based in Springfield but with its factory in Lewiston, Maine) and Knox Automobile. In 1905, Knox produced America's first motorized fire engines, for the Springfield Fire Department. Stevens-Duryea built cars in East Springfield from 1901 to 1915, and again from 1919 to 1927.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

‘Working people the world over have celebrated the first of May as “International Labor Day” since 1886, when workers in the United States struggling for an eight-hour day staged a May 1 national protest.

Thanks to the new deal America’s auto workers have signed with Detroit’s Big Three — Ford, GM and Stellantis — that day could have new global significance. Their watershed new contracts all set April 30, 2028 as their expiration date.

If May 1, 2028 arrives without signed contracts for America’s unionized auto workers, UAW president Shawn Fain has made plain, these workers don’t plan on walking out alone.

“We invite unions around the country to align your contract expirations with our own so that together we can begin to flex our collective muscles,” says Fain. “If we’re going to truly take on the billionaire class and rebuild the economy so that it starts to work for the benefit of the many and not the few, then it’s important that we not only strike but that we strike together.”

But that May 1 day is clearly inviting coordination beyond the national level.

The May Day that workers worldwide have so long honored, Fain notes, has always been “more than just a day of commemoration, it’s a call to action.” And the labor movement worldwide is showing real signs of acting more in strategic concert.

Within the global auto industry, no corporation more embodies the inequality of our corporate world than the non-union Tesla. Under CEO Elon Musk, the world’s richest individual, Tesla pays wages that run substantially below those of Detroit’s Big Three, and that gap will only widen after the new UAW contracts go into effect.

The new UAW contracts, predicts German Bender of the Swedish think-tank Arena, could well “boost union interest among Tesla workers.”

That interest already seems to be growing. On the final Friday of the UAW walkout in the United States, workers at Tesla-owned servicing shops in Sweden went out on strike — after five years of fruitless attempts to get Tesla’s Swedish subsidiary to reach a bargaining agreement. That strike has now spread to all auto shops in Sweden that do work on Tesla cars.

This Swedish walkout represents the first formal strike against Tesla anywhere in the world. And the challenge to Tesla may be spreading. Germany’s largest union, Bloomberg reports, is hoping to organize a 12,000-worker Tesla plant near Berlin.

Tesla’s over 120,000 workers worldwide will see plenty to like in the new UAW contracts in the United States. At Ford, workers who started as temps making $16.67 an hour will automatically move to permanent status and an hourly wage rate of at least $24.91. That rate will hit $40.82 by the contract’s end, and any inflation between now and then will kick that rate higher.

Workers in major American industries haven’t seen gains that stunning since the middle of the 20th century, a time when the chief executives of America’s largest corporations averaged only just over 20 times the compensation of their workers. That gap today, the Economic Policy Institute calculates, is now running nearly 350 times.

But the greatest significance of the new UAW auto industry contracts may be the impact these bargaining triumphs will have on the future. These agreements could become the single most important step to a more equal world that any of us have ever seen.

The giants of American auto manufacturing, as Fain puts it, “underestimated” their own workers’ capacity to unite and fight together.

“We have shown the companies, the American public, and the whole world that the working class is not done fighting,” he adds. “In fact, we’re just getting started.”

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Tom Conway: OT rules put lives at risk and strain families

The paper mill town of Madawaska, Maine

—Photo by P199

Via OtherWords.org

She only wanted a few hours at her dying mother’s bedside. But her bosses at Twin Rivers Paper, in Madawaska, Maine, forced her to work overtime on her day off. About an hour and a half into the mandatory shift, the woman’s mother died.

Workers are battling harder than ever to end this appalling mistreatment. They’re fighting back against mandatory overtime requirements that strain families to the breaking point and put lives at risk.

“It’s definitely caused a lot of heartache,” said David Hebert, financial officer and former president of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 291, one of three USW locals collectively representing about 360 workers at Twin Rivers.

USW members have long warned paper companies about the need to increase hiring and training to keep facilities operating safely. Yet some employers prefer to work people to the bone. Workers at Twin Rivers work a base shift of 12 hours — and each can be drafted for an additional 12-hour shift every month.

Even worse, a 12-hour shift can be extended with six hours of mandatory overtime without warning. Workers are often forced to pull multiple 18-hour days a week, especially when winter cold and flu season exacerbates the company’s intentional understaffing.

“People really hold their breath at the end of their shift,” explained Hebert. The coworker who lost her mother, for example, learned at the end of an 18-hour shift that she’d have to report the following day for overtime.

Other workers experience their own heartaches when unpredictable schedules leave them unable to make plans with their families or force them to miss graduations, anniversaries, birthday parties, or holiday gatherings.

“Family is the only reason we go into these places. I want to spend time with them, too,” said Justin Shaw, president of USW Local 9, which represents workers at Sappi’s Somerset Mill, in Skowhegan, Maine.

“You’ve got many people who work seven days a week,” with some required to log 24 hours at a stretch, Shaw said. “If we had better staffing levels, we wouldn’t have people working outrageous hours.”

Besides the toll it takes on family life, excessive overtime compounds risk in an industry that exposes workers to hazardous chemicals, fast-moving machinery, super-hot liquids and huge rolls of paper.

“It only takes a split second to lose a finger, an arm, or a life,” Shaw said, warning that extreme fatigue also puts workers at risk while commuting. “I’ve had many drives home that I can’t recall over half the ride. We have had many individuals in the ditch or wreck vehicles trying to keep up with the demands.”

A bill in Maine would limit mandatory overtime to no more than two hours a day and require employers to provide a week’s notice before mandating extra hours or changing a worker’s schedule.

The legislation places no caps on voluntary overtime, nor would it apply to true emergencies when a mill needs extra hands to avert “immediate danger to life or property.” But it would end the capricious usurping of workers’ lives that now occurs because the industry refuses to hire enough people.

Union members also continue to drive change at the bargaining table. Some workers are pushing to create “share pools” of workers whose role is to fill in where needed on a given shift.

“Share pools” virtually eliminated mandatory overtime at the Huhtamaki facility in Waterville, Maine, where workers once had to put in so many hours that some slept in their cars rather than commute home, said Lee Drouin, president of USW Local 449.

Drouin said other paper companies also need to realize that change is essential for workers but benefits them as well. “The mills have to understand, this is not going to go away,” he said. “To me, it makes a lot more sense to have happy workers and safe workers.”

Tom Conway is the international president of the United Steelworkers Union (USW). This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute and adapted for syndication by OtherWords.org.