Llewellyn King: AI and our robotic future

The robot Maria from the 1927 German expressionist film Metropolis

Editor’s Note: Visit the fabulous MIT Museum, in Cambridge, Mass., to check robotic-related stuff.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The next big thing is robots. They are, you might say, on the move.

Within five years, robots will be doing a lot of things that people now do. Simple repetitive work, for example, is doomed.

Already, robots weld, bolt and paint cars and trucks. The factory of the future will have very few human workers. Amazon distribution centers are almost entirely robot domains. Robots search the shelves, grab items, pack and send them to you — often seconds after you have placed your order.

Of course, these orders will be delivered in vans, which must be loaded carefully, even scientifically. The first out must be the last in; small items must nestle with large ones. Space is at a premium, so robotic brains will do the sorting and packing swiftly, efficiently and inexpensively.

Very soon, the van will be self-driving: a robot capable of navigating the traffic and finding your home. At first, it may not get further in the delivery chain than calling you to say that your package has arrived. Eventually, humanoid robots may ride in the vans and, yes, hand your package to you. No tipping, please.

When we think about robots, we tend to think of the robots that look like us. The internet is full of clips of them climbing stairs, playing sports and doing backflips.

There are reasons for humanoid robots: They are less intimidating with their humanlike heads, two arms with hands and two legs with feet than a machine with many arms or legs. Also, most of the tasks the robot is taking over are done by humans. The tasks are fitted to people, such as pumping gas, preparing vegetables or painting a wall.

The first big incursion may be robotaxis. Waymo taxis are already operating in five cities, and the company has plans to roll them out in 19 cities. Several cities are concerned about safety, including Houston and Seattle, and want to ban them. But there are state-city jurisdictional issues about implementing bans.

A likely scenario, as with other bans, is that the development will go elsewhere. Travelers tend to eschew places where Uber and Lyft aren’t allowed to operate in favor of those where they are.

You are already dealing with robots when you talk to a digital assistant at an airline, a bank, a credit card or insurance company, or any business where you call a helpline. That soothing, friendly voice that comes on immediately and asks practical questions may be a robot: the unseen voice of artificial intelligence.

In the years I have been writing about AI and its impact on society, I have consistently heard the AI revolution and its impact on jobs compared with the Industrial Revolution and automation. The one led to the other and in the end, many new jobs and whole new ecosystems flourished.

It isn’t clear that this will happen again and if so on what timetable. A lot of jobs are already in danger, from file clerks to delivery and taxi drivers, from warehouse workers to longshoremen.

AI is also changing the tech world. A whole new tier of companies is emerging to carry forward the AI-robot revolution. These are companies that make robots; companies that write software, which will give robots brainpower; and companies that will have a workforce that maintains robots.

These emerging companies will need a workforce with a different set of skills — skills that will keep the new AI economy humming.

What is missing is any sense that the political class has grasped the tsunami of change that is about to break over the nation. In just a few years, you may be riding in a robotaxi, watching a humanoid robot doing yard work or lying on a couch and chatting with your robot psychiatrist.

Our species is adaptable, and we have adapted everything from the wheel to the steam engine to electricity to the internet. And we have prospered.

Time to think about how to prosper with AI and its robots.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, as well as an international energy-sector consultant. He’s also a former publisher and editor.

Llewellyn King: Journalism is a business of serial judgment under pressure

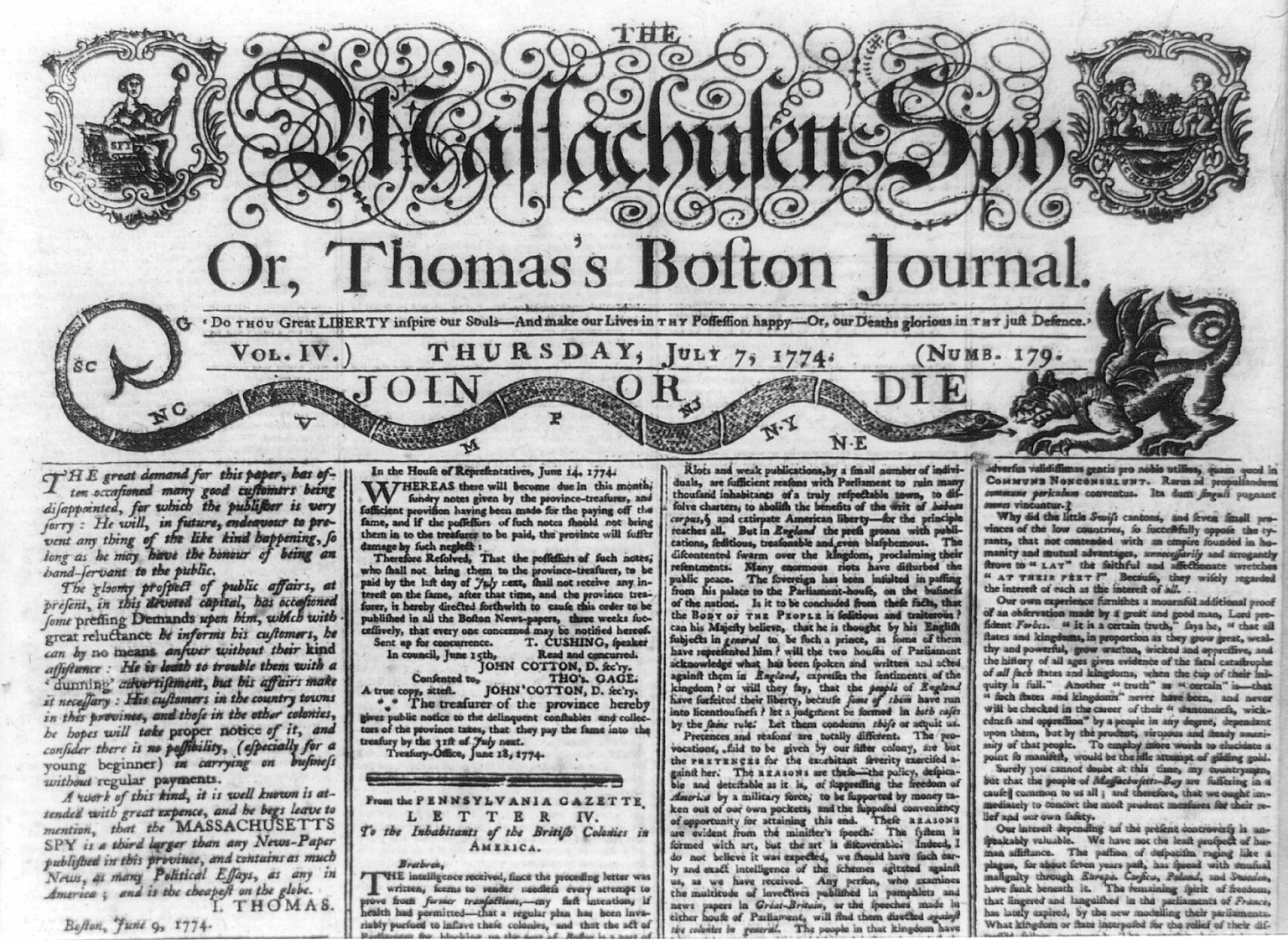

An example of the nonobjective newspapers that dominated American journalism until ideals of objective rep0rting slowly started to take hold around the turn of the 20th Century in larger cities.

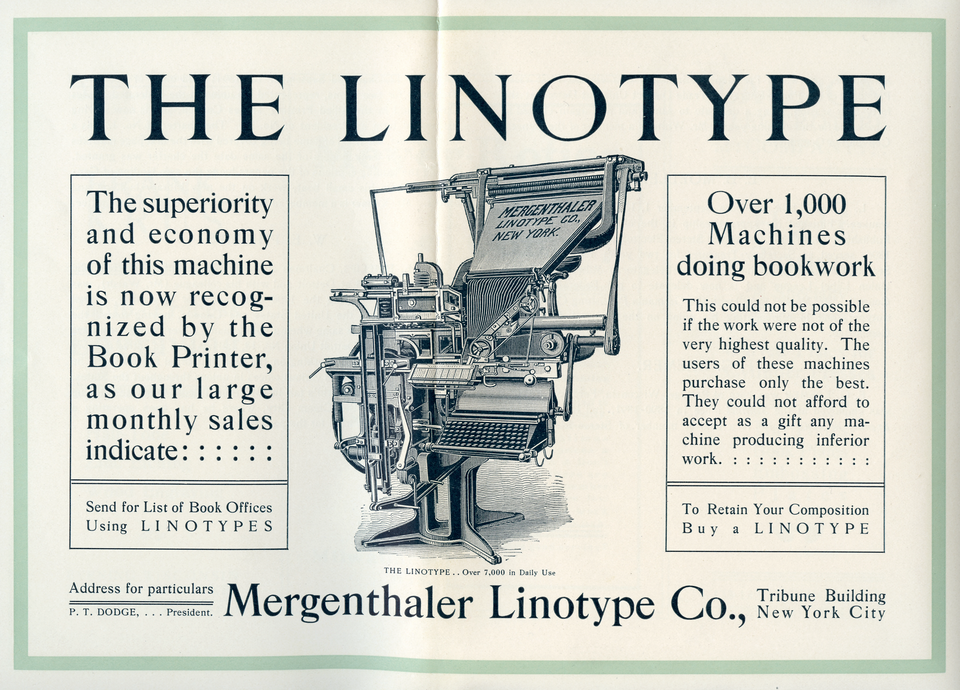

The Linotype machine was very important in newspaper printing until computerization doomed it.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The BBC has fallen on its sword. The director general has resigned and so has the head of news over the splicing of tape of President Trump's rambling speech on Jan. 6, 2021, which preceded the sacking of the Capitol by his fanatical followers.

The editor and the technician who did the deed for the esteemed BBC program Panorama haven't been publicly identified.

Agreed, they shouldn't have done what they did. But was there malice?

Journalism is a business of serial judgment. It is replete with mistakes — things that we who practice the craft wish we hadn't done.

I have worked as an editor in film, with tape and on newspapers, and I have seen how the paranoia of politicians can cast a whole news organization as a biased enemy when that wasn't the case.

Before a single sentence or an article appears in a newspaper or a video appears on television, dozens of judgments have been made — not by teams of academics or by ethicists or by juries, but by individuals responding to time pressure and what they judge to be newsworthy.

The unsaid pressure to keep it interesting, to have news worth something, is always there. The reader has to be kept reading or the viewer watching.

After something is published or broadcast, it can be beacon-clear what should have been done or corrected, but in the moment, those defects are opaque.

Let me take you behind the veil.

It is a hot night in 1972. There is a presidential election brewing and among those running for the Democratic nomination is Henry “Scoop" Jackson, the well-known Democratic senator from the state of Washington.

I am working in the composing room of The Washington Post as the editor in charge of liaising between the printers and the editors. The job is sometimes called a stone editor after the “stone’’ — big metal tables that held the pages and where the newspaper was assembled in the days of hot type via Linotype machines.

It was a busy news night, and it was when David Broder was the political reporter without rival. He was industrious and thorough, dedicated and prolific. As the night wore on, Broder would often add new stuff to his story, and it would grow in length.

In desperation when things got tough and deadlines were pressing, we would cut back the size of the photos, which had run in the first edition. The editor on duty would just ask the printers to do this: It was known as “whacking the cut."

In short, the photo would be reduced in size by cutting it down physically. The engraving would be put in a guillotine and some of it would be cut off, whacked.

That night, we had a large photo of Jackson addressing a large crowd.

But as the night wore on and different editions and mini editions, known as replates, were assembled, I ordered the cut whacked and whacked again. The result was that by the time the main edition went to press, the good senator was talking to a much smaller audience — although it did suggest that many more were there but not seen.

Jackson thought that this was a deliberate bias by The Post to suggest that he couldn't draw a large audience, and he called the legendary executive editor Ben Bradlee.

Bradlee asked the national editor, Ben Bagdikian, who was to become an authority on newspaper ethics, what happened. When they came to me, I explained how we trimmed the pictures.

While Bradlee was amused, Bagdikian added it to his concern about newspaper ethics.

Journalism is executed by individuals under pressure, much of it intense. It is a business of multiple judgments made sequentially, often without a lot of contemplation.

I once worked at the BBC in London, and the same pressures were present. I was scriptwriter and editor on the evening news. You made decisions all the time: This frame in, those 20 frames out. An outsider might imagine prejudice and foul intent in the way one clip was used and others were not.

In the news trade, judgments can trip you up, but making judgments is essential. Later the judge is judged, as at the BBC.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based mostly in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He was a long-time publisher and remains an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: The biggest sources of stress for air-traffic controllers

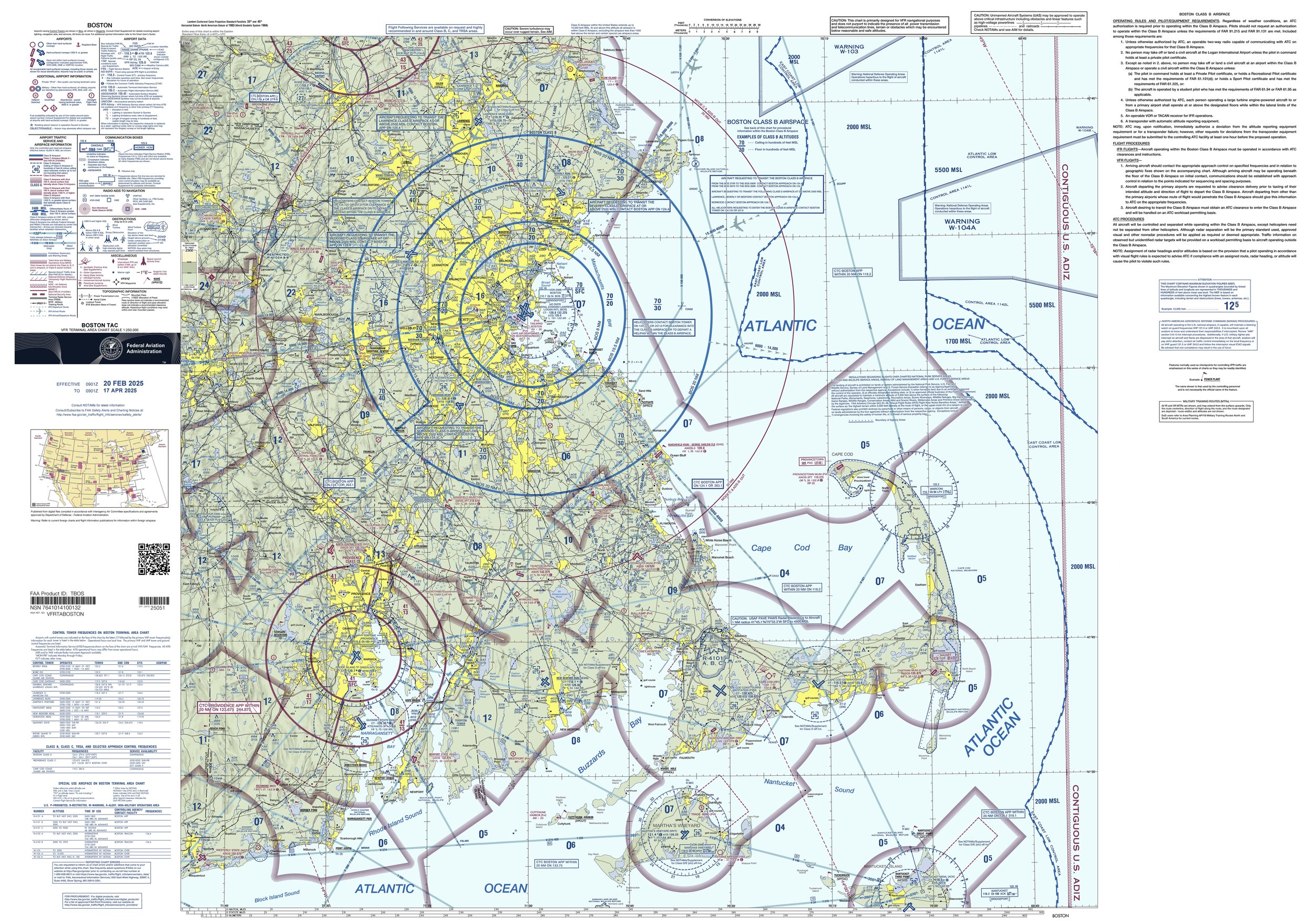

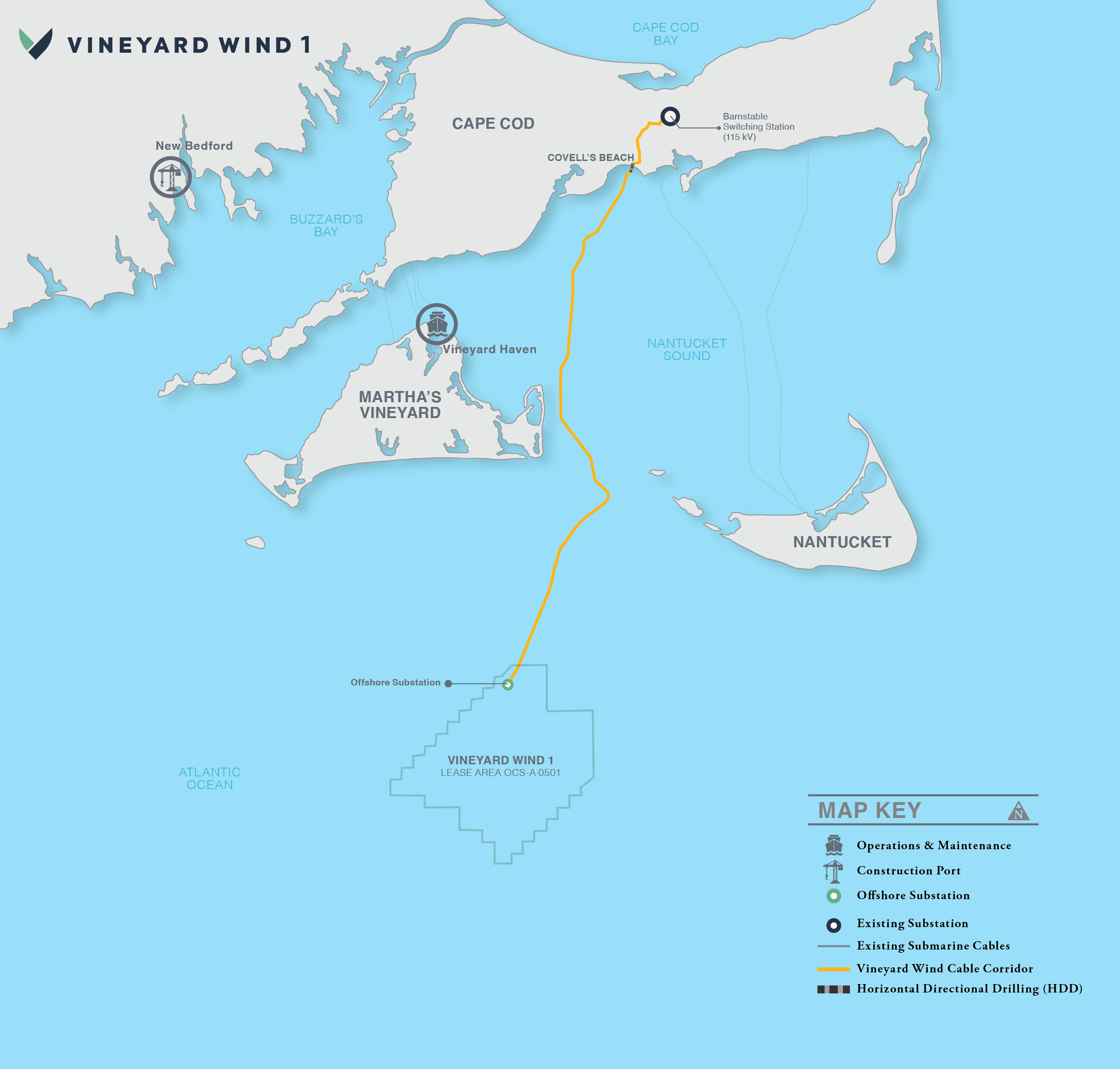

Air-traffic-control zones in the southeast corner of New England.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If you don't know about the stress that air-traffic controllers are reportedly under, then maybe you are an air-traffic controller.

The fact is that air-traffic controllers love what they do — love it and wouldn't do anything else.

The stress comes with long hours, Federal Aviation Administration bureaucracy and a general lack of recognition, not with moving airplanes safely about the sky.

Of course, I haven't interviewed every controller, but I have talked to a lot of them over the years and have been in many control towers.

Controllers love the essentiality of it. They love aviation in all its forms.

They love the man-and-machine interface, which is at the heart of modern aviation. They love the sense of being part of a great system — the power, the language, the satisfaction.

They love the trust that every pilot puts in them. It is rewarding to be trusted in anything, but more so when the price of failure is known.

Nearly everything that is true of pilots is true of controllers. At its heart, the job is about flight, arguably the greatest achievement of mankind, the fulfillment of millennia of yearning.

There is a saying often attributed to Winston Churchill that was actually said by a pilot and insurance executive in the 1930s: “Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

That is true both of pilots and those at the consoles on the ground, who co-fly with them.

After President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking controllers in 1981, some of the saddest people I knew were air-traffic controllers.

They were denied the right to do the work that they loved and suffered immeasurably for that. A few were able to get work overseas, but mostly it was a light that went out and stayed out.

I ran into one former controller, working as a baggage handler. He said he just wanted to be near the action even if he couldn't go into the tower anymore and do his dream job.

My only major criticism of Reagan in this case has always been that he didn't rehire the strikers after he had won, proving that they were wrong in striking illegally and that they weren't above the law.

Reagan was often a compassionate man, but he showed the controllers no compassion. I think that if he had understood the psychological pain he had inflicted, he would have relented.

Controllers have explained to me that if a controller finds the job stressful, then he or she shouldn't be a controller.

About one-third of the candidates for controllers' school, most of whom are trained at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, flunk out.

It takes longer to train a controller than a pilot — maybe not to work in the cockpit of a passenger jet, but certainly to fly an aircraft, including jets. It takes at least four years of schooling, simulator and then supervised controlling to qualify to be an FAA controller. Some controllers come from the military.

There is just one movie about air-traffic control, released in 1999, Pushing Tin. It flopped at the box office but has a cult following among pilots and controllers. It is funny and accurate. Pushing tin is controllers' jargon for what they do: push airplanes around the sky.

The fabled stress, in my mind, is the adrenaline factor. It is present in air-traffic control, and it is present in the cockpit of everything that leaves the ground, from single-engine Cessnas to Boeing 777s — and in ATC facilities.

It interests me that pilots rarely mention stress. It is, however, always mentioned by people writing about or talking about air-traffic control. I would venture that the most stress that controllers deal with is the stress imposed on them by the FAA.

I will aver that in the recent and record-long government shutdown, the largest source of stress for controllers was how they were going to put food on the table and pay their bills, not the stress that they feel at the console, pushing tin and keeping flying safe. Now they are stressed about back pay.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: The agony of statelessness

Stateless children at at the Schauenstein, Germany, displaced-persons camp in about 1946. There were millions of displaced and stateless people in Europe as World War II ended.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have only known one stateless person. You don't get a medal for it or wear a lapel pin.

The stateless are the hapless who live in the shadows, in fear.

They don't know where the next misadventure will come from: It could be deportation, imprisonment or an enslavement of the kind the late Johnny Prokov suffered as a shipboard stowaway for seven years.

His story ended well, but few do.

When I knew Johnny, he was a revered bartender at the National Press Club in Washington. By then, he had American citizenship, was married and lived a normal life.

It hadn't always been that way. He told me that he had come from Dalmatia, when that area was so poor people took their clothes to a specialist who would kill the lice in the seams with a little wooden mallet, which wouldn't damage the cloth.

To escape that extreme poverty, Prokov became a stowaway on a ship.

So began his seven-year odyssey of exploitation and fear of violence. The captains took advantage of the free labor and total servitude of the stowaways.

Eventually, Prokov jumped ship in Mexico. He made his way to the United States, where a life worth living was available.

I don't know the details of how he became a citizen, but he dreamed the American dream — and it came true for him.

An odd legacy of his years at sea was that Prokov had become a brilliant chess player. He would often have as many as a dozen chess games going along the bar in the National Press Club. He always won. He had had time to practice.

The United Nations says there are 4 million stateless people in the world, but that is a massive undercount. Many of those who are stateless are refugees and have no idea if they are entitled to claim citizenship of the countries they are desperate to escape from. Citizenship in Gaza?

Now the Trump administration wants to add to the number of stateless people by denying birthright citizenship to children born of illegal immigrants in the United States.

It wants to deny people — who are in all ways Americans — their constitutional right of citizenship. Their lives will be lived on a lower rung than their friends and contemporaries. They will be denied passports, maybe education, possibly medical care, and the ability to emigrate to any country that otherwise might have received them.

Instead, they will live their lives in the shadows, children of a lesser God, probably destined to have children of their own who might also be deemed noncitizens. They didn't choose the womb that bore them, nor did they sanction the actions of their parents.

The world is awash in refugees fleeing war, crime and violence, and environmental collapse. Those desperate people will seek refuge in countries which can't absorb them and will take strong actions to keep them out, as have the United States and, increasingly, countries in Europe.

There is a point, particularly in Europe, where the culture, including established religion, is threatened by different cultures and clashing religions.

But when it comes to children born in America to mothers who live in America, why mint a new class of stateless people, condemned to a second-class life here, or deport them to some country, such as Rwanda or Uganda, where its own people are already living in abject poverty?

All immigrants can't be accommodated, but the cruelty that now passes for policy is hurtful to those who have worked hard and dared to seek a better life for themselves and their children.

It is bad enough that millions of people are seeking somewhere to live and perchance a better life, due to war or crime or drought or political follies.

To extend the numbers by denying citizenship to the children of parents who live and work here isn't good policy. It is also unconstitutional.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the administration, it will add social instability of haunting proportions.

Children are proud of their native lands. What will the new second class be proud of — the home that denied them?

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Will AI launch a shadow government that can catch Trump, et al., trying to cook the books?

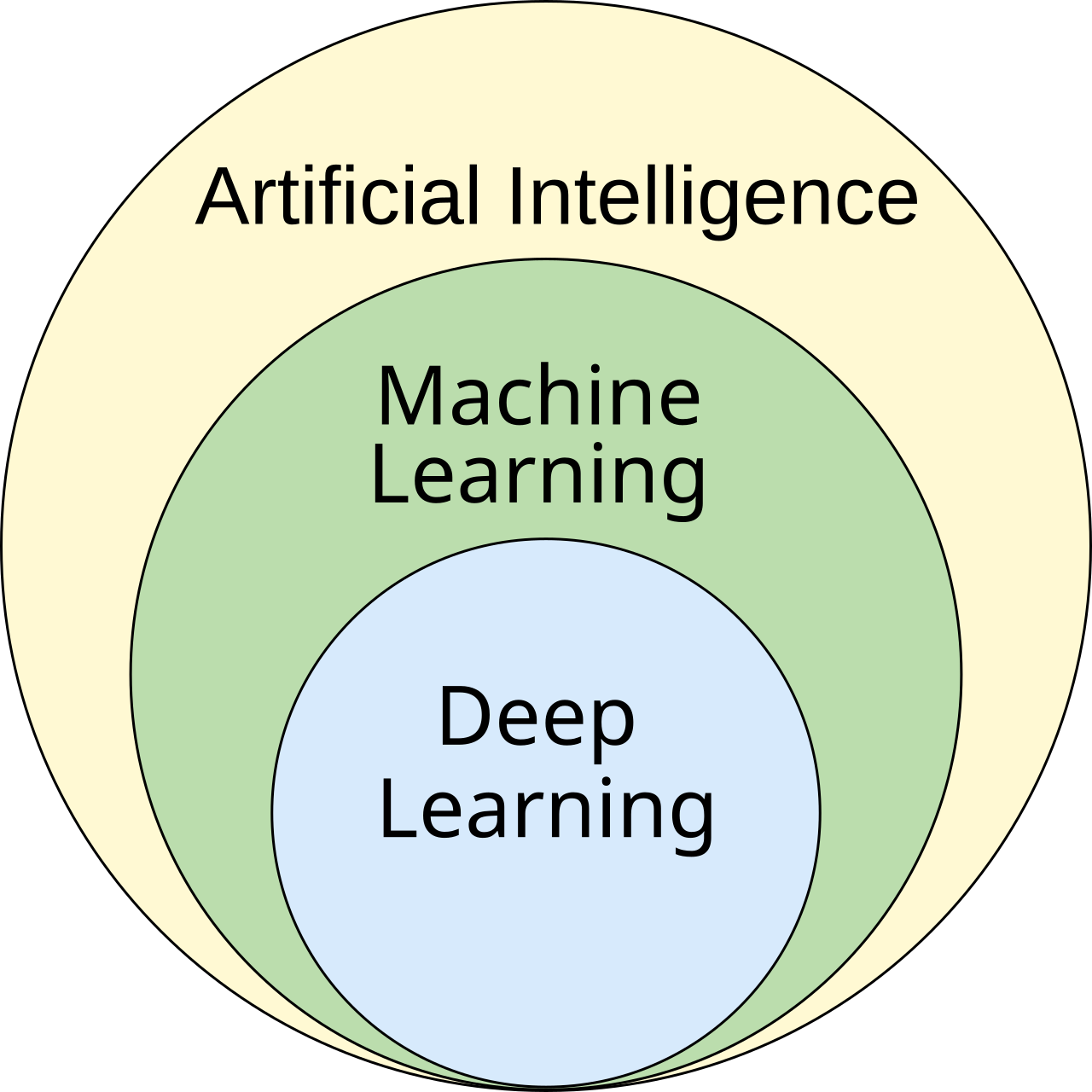

Read about a meeting of the minds at a summer workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956 that helped launch artificial intelligence as a discipline and gave it a name.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

This Time It’s Different is the title of a book by Omar Hatamleh on the impact of artificial intelligence on everything.

By this Hatamleh, who is NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s chief artificial intelligence officer, means that we shouldn’t look to previous technological revolutions to understand the scope and the totality of the AI revolution. It is, he believes, bigger and more transformative than anything that has yet happened.

He says AI is exponential and human thinking is linear. I think that means we can’t get our minds around it.

Jeffrey Cole, director of the Center For the Digital Future at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, echoes Hatamleh.

Cole believes that AI will be as impactful as the printing press, the internet and COVID-19. He also believes 2027 will be a seminal year: a year in which AI will batter the workforce, particularly white-collar workers.

For journalists, AI presents two challenges: jobs lost to AI writing and editing, and the loss of truth. How can we identify AI-generated misinformation? The New York Times said simply: We can’t.

But I am more optimistic.

I have been reporting on AI since well before ChatGPT launched in November 2022. Eventually, I think AI will be able to control itself, to red flag its own excesses and those who are abusing it with fake information.

I base this rather outlandish conclusion on the idea that AI has a near-human dimension which it gets from absorbing all published human knowledge and that knowledge is full of discipline, morals and strictures. Surely, these are also absorbed in the neural networks.

I have tested this concept on AI savants across the spectrum for several years. They all had the same response: It is a great question.

Besides its trumpeted use in advancing medicine at warp speed, AI could become more useful in providing truth where it has been concealed by political skullduggery or phony research.

Consider the general apprehension that President Trump may order the Bureau of Labor Statistics to cook the books.

Well, aficionados in the world of national security and AI tell me that AI could easily scour all available data on employment, job vacancies and inflation and presto: reliable numbers. The key, USC’s Cole emphasizes, is inputting complete prompts.

In other words, AI could check the data put out by the government. Which leads to the possibility of a kind of AI shadow government, revealing falsehoods and correcting speculation.

If AI poses a huge possibility for misinformation, it also must have within it the ability to verify truth, to set the record straight, to be a gargantuan fact checker.

A truth central for the government, immune to insults, out of the reach of the FBI, ICE or the Justice Department —and, above all, a truth-speaking force that won’t be primaried.

The idea of shadow government isn’t confined to what might be done by AI, but is already taking shape where DOGEing has left missions shattered, people distraught and sometimes an agency unable to perform. So, networks of resolute civil servants inside and outside government are working to preserve data, hide critical discoveries and to keep vital research alive. This kind of shadow activity is taking place at the Agriculture, Commerce, Energy and Defense departments, the National Institutes of Health and those who interface with them in the research community.

In the wider world, job loss to AI, or if you want to be optimistic, job adjustment has already begun. It will accelerate but can be absorbed once we recognize the need to reshape the workforce. Is it time to pick a new career or at least think about it?

The political class, all of it, is out to lunch. Instead of wrangling about social issues, it should be looking to the future, a future which has a new force, much as automation was a force to be accommodated, this revolution can’t be legislated or regulated into submission, but it can be managed and prepared for. Like all great changes, it is redolent with possibility and fear.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Llewellyn King: Sorry, Trump, solar and wind power will keep growing in U.S.; utilities urgently need them

BlueWave's 5.74 MW DC, 4 MW community solar project in Orrington, Maine. It’s one of the largest such facilities in New England.

—Courtesy: BlueWave

The small wind farm off Block Island.

Vineyard Wind 1 is partly operating.

This commentary was originally published in Forbes.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Trump reiterated his hostility to wind generation when he recently arrived in Scotland for what was ostensibly a private visit. “Stop the windmills,” he said.

But the world isn’t stopping its windmill development and neither is the United States, although it has become more difficult and has put U.S. electric utilities in an awkward position: It is a love that dare not speak its name, one might say.

Utilities love that wind and solar can provide inexpensive electricity, offsetting the high expense of battery storage.

It is believed that Trump’s well-documented animus to wind turbines is rooted in his golf resort in Balmedie, near Aberdeen, Scotland. In 2013, Trump attempted to prevent the construction of a small offshore wind farm — just 11 turbines — roughly 2.2 miles from his Trump International Golf Links, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He argued that the wind farm would spoil views from his golf course and hurt tourism in the area.

Trump seemingly didn’t just take against the local authorities, but against wind in general and offshore wind in particular.

Yet fair winds are blowing in the world for renewables.

Francesco La Camera, director general of the International Renewable Energy Agency, an official United Nations observer, told me that in 2024, an astounding 92 percent of new global generation was from wind and solar, with solar leading wind in new generation. We spoke recently when La Camera was in New York.

My informal survey of U.S. utilities reveals they are pleased with the Trump administration’s efforts to simplify licensing and its push to natural gas, but they are also keen advocates of wind and solar.

Simply, wind is cheap and as battery storage improves, so does its usefulness. Likewise, solar. However, without the tax advantages that were in President Joe Biden’s signature climate bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, the numbers will change, but not enough to rule out renewables, the utilities tell me.

China leads the world in installed wind capacity of 561 gigawatts, followed by the United States with less than half that at 154 GW. The same goes for solar installations: China had 887 GW of solar capacity in 2024 and the United States had 239 GW.

China is also the largest manufacturer of electric vehicles. This gives it market advantage globally and environmental bragging rights, even though it is still building coal-fired plants.

While utilities applaud Trump’s easing of restrictions, which might speed the use of fossil fuels, they aren’t enthusiastic about installing new coal plants or encouraging new coal mines to open. Both, they believe, would become stranded assets.

Utilities and their trade associations have been slow to criticize the administration’s hostility to wind and solar, but they have been publicly cheering gas turbines.

However, gas isn’t an immediate solution to the urgent need for more power: There is a global shortage of gas turbines with waiting lists of five years and longer. So no matter how favorably utilities look on gas, new turbines, unless they are already on hand or have set delivery dates, may not arrive for many years.

Another problem for utilities is those states that have scheduled phasing out fossil fuels in a given number of years. That issue – a clash between federal policy and state law — hasn’t been settled.

In this environment, utilities are either biding their time or cautiously seeking alternatives.

For example, facing a virtual ban on new offshore wind farms, veteran journalist Robert Whitcomb wrote in his New England Diary that the New England utilities are looking to wind power from Canada, delivered by undersea cable. Whitcomb co-wrote (with Wendy Williams) a book, Cape Wind: Money, Celebrity, Energy, Class, Politics and the Battle for Our Energy Future, about offshore wind, published in 2007.

New England is starved of gas as there isn’t enough pipeline capacity to bring in more, so even if gas turbines were readily available, they wouldn’t be an option. New pipelines take financing, licensing in many jurisdictions, and face public hostility.

Emily Fisher, a former general counsel for the Edison Electric Institute, told me, “Five years is just a blink of an eye in utility planning.”

On July 7, Trump signed an executive order which states: “For too long the Federal Government has forced American taxpayers to subsidize expensive and unreliable sources like wind and solar.

“The proliferation of these projects displaces affordable, reliable, dispatchable domestic energy resources, compromises our electric grid, and denigrates the beauty of our Nation’s natural landscape.”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration puts electricity consumption growth at 2 percent nationwide. In parts of the nation, as in some Texas cities, it is 3 percent.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island

Llewellyn King: The joy of friendship; a very dark Fourth; ‘customer service’ oxymoron; AI in medicine

Masked people wearing this badge made it a less than Glorious Fourth. It’s our new secret police.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I treasure the friends who share their friends. One of those friends, Virginia “Ginny” Hamill, has died.

I met Ginny at The Washington Post in 1969, and we became forever-friends.

Ginny had an admirable ascent from a teleprinter operator to an editor in The Washington Post/Los Angeles Times News Service. She was promoted again to the enviable job as the editor of the news service in London, where she bloomed — and met her future husband, John McCaughey.

Ginny brought wealth into my life — and later to that of my wife, Linda Gasparello — through the introductions to her friends from that London period. They included David Fishlock, science editor of the Financial Times; Roy Hodson, also of the FT; Deborah Waroff, an American journalist; and Guy Hawtin, a rakish newspaperman on his way to the New York Post.

They constituted what I called “The Set.” In London, New York and Washington, we worked at the journalism trade on many projects from newsletters to conferences and broadcasts.

We also partied; it went with the territory.

I once wrote to Ginny and told her how instrumental she had been in all our lives through sharing her friends. I am glad I didn’t wait until obituary time to thank her for her generosity in friend-sharing.

******

I think that for many, myself among them, it was a somber July 4. There are dark clouds crossing America’s sun. There are things aplenty going on that seem at odds with the American ideal, and the America we have known.

To me, the most egregious excess of the present is the way masked agents of the state grab men, women and children and deport them without due process, without observance of a cornerstone of law: habeas corpus. None are given a chance to show their legality, call family or, if they have one, a lawyer.

This war against the defenseless is wanton and cruel.

The advocates of this activity, this snatch-and-deport policy, say, and have said it to me, “What do these people not understand about ‘illegal’?”

I say to these advocates, “What don’t you understand about want, need, fear, family, marriage, children and hope?”

The repression many fled from has reentered their luckless lives: terror at the hands of masked enforcers.

I have always advocated for controlled immigration. But the fact that it has been poorly managed shouldn’t be corrected post facto, often years after the offense of seeking a better life and without the consideration of contributions to society.

Meanwhile, the media remain under attack, the universities are being coerced, and the courts are diminished.

America has always had blots on its history, but it has also stood for justice, for the rule of law, for freedom of the press, freedom of speech. Violations of these values dimmed the Fourth.

America deserves better: Think of the Constitution, one of the all-time great documents of history, a straight-line descendant of the Magna Carta of 1215. That was when the noblemen of England told King John, “Cut it out!”

A few noblemen in Washington wouldn’t go amiss.

I was fortunate on my syndicated television show, White House Chronicle, along with my co-host, Adam Clayton Powell III, to recently interview Harvey Castro, an emergency room doctor. Castro, from a base in Dallas, has seized on artificial intelligence as the next frontier in health care.

He has written several books and given TEDx talks on the future of AI-driven health care. I have talked to several doctors in this field, but never one who sees the application of AI in as many ways from diagnosing ailments through a patient's speech, to having an AI -controlled robot assist a nurse to gently transfer a patient from a gurney to a bed.

A man with infectious ebullience, Castro says his frustration in emergency rooms was that he got there too late: after a heart attack, stroke or seizure. He expects AI to change that through predictive medicine and early treatment.

His work has caught the attention of the government of Singapore, and he is advising them on how to build AI into their medical system.

******

Like everyone else, I spend a lot of time in frustration-agony on the phone when I need to talk to a bank or insurance company and many other firms that have “customer service.” That phrase might loosely be translated as “Get rid of the suckers!”

I don’t know whether the arrival of AI agents will hugely improve customer service, but maybe you can banter with them, get them to deride their masters, even to tell you stuff about the president of the bank.

It might be easier talking to an AI agent than talking to someone with a script in another country before they inevitably, but oh, so nicely, tell you to get lost, as happened to me recently.

You could enjoy a little hallucinatory fun with a virtual comedic friend, before it tells you to have a nice day, and hangs up.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Low-lying wind turbines could be revolutionary

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Jimmy Dean, the country musician, actor and entrepreneur, famously said: “I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.”

A new wind turbine from a California startup, Wind Harvest, takes Dean’s maxim to heart and applies it to windpower generation. It goes after untapped, abundant wind.

Wind Harvest is bringing to market a possibly revolutionary but well-tested vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) that operates on ungathered wind resources near the ground, thriving in turbulence and shifting wind directions.

The founders and investors – many of them recruited through a crowd-funding mechanism — believe that wind near the ground is a great underused resource that can go a long way to helping utilities in the United States and around the world with rising electricity demand.

The Wind Harvest turbines would not be used to replace nor compete with the horizontal axis wind turbines (HAWT), which are the dominant propeller-type turbines seen everywhere. These operate at heights from 200 feet to 500 feet above ground.

Instead, these vertical turbines are at the most 90 feet above the ground and, ideally, can operate beneath large turbines, complementing the tall, horizontal turbines and potentially doubling the output from a wind farm.

The wind disturbance from conventional tall, horizontal turbines is additional wind fuel for vertical turbines sited below.

Studies and modeling from CalTech and other universities predict that the vortices of wind shed by the verticals will draw faster-moving wind from higher altitude into the rotors of the horizontals.

For optimum performance, their machines should be located in pairs just about 3 feet apart and that causes the airflow between the two turbines to accelerate, enhancing electricity production.

Kevin Wolf, CEO and co-founder of Wind Harvest, told me that they used code from the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratory to engineer and evaluate their designs. They believe they have eliminated known weaknesses in vertical turbines and have a durable and easy-to-make design, which they call Wind Harvester 4.0.

This confidence is reflected in the first commercial installation of the Wind Harvest turbines on St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean. Some 100 turbines are being proposed for construction on a peninsula made from dredge spoils. This 5-megawatt project would produce 15,000 megawatt hours of power annually.

All the off-take from this pilot project will go to a local oil refinery for its operations, reducing its propane generation.

Wolf said the Wind Harvester will be modified to withstand Category 5 hurricanes; can be built entirely in the United States of steel and aluminum; and are engineered to last 70-plus years with some refurbishing along the way. Future turbines will avoid dependence on rare earths by using ferrite magnets in the generators.

Recently, there have been various breakthroughs in small wind turbines designed for urban use. But Wind Harvest is squarely aimed at the utility market, at scale. The company has been working solidly to complete the commercialization process and spread VAWTs around the world.

“You don’t have to install them on wind farms, but their highest use should be doubling or more the power yield from those farms with a great wind resource under their tall turbines,” Wolf said.

Horizontal wind turbines, so named because the drive shaft is aligned horizontally to the ground, compared to vertical turbines where the drive shaft and generator are vertically aligned and much closer to the ground, facilitating installation, maintenance and access.

Wolf believes that his engineering team has eliminated the normal concerns associated with VAWTs, like resonance and the problem of the forces of 15 million revolutions per year on the blade-arm connections. The company has been granted two hinge patents and four others. Three more are pending.

Wind turbines have a long history. The famous eggbeater-shaped VAWT was patented by a French engineer, Georges Jean Marie Darrieus, in 1926, but had significant limitations on efficiency and cost-effectiveness. It has always been more of a dream machine than an operational one.

Wind turbines became serious as a concept in the United States as a result of the energy crisis that broke in the fall of 1973. At that time, Sandia began studying windmills and leaned toward vertical designs. But when the National Renewable Energy Laboratory assumed responsibility for renewables, turbine design and engineering moved there; horizontal was the design of choice at the lab.

In pursuing the horizontal turbine, DOE fit in with a world trend that made offshore wind generation possible but not a technology that could use the turbulent wind near the ground.

Now, Wind Harvest believes, the time has come to take advantage of that untouched resource.

Wolf said this can be done without committing to new wind farms. These additions, he said, would have a long-projected life and some other advantages: Birds and bats seem to be more adept at avoiding the three-dimensional, vertical turbines closer to the surface. Agricultural uses can continue between rows of closely spaced VAWTs that can align fields, he added.

Some vertical turbines will use simple, highly durable lattice towers, especially in hurricane-prone areas. But Wolf believes the future will be in wooden, monopole towers that reduce the amount of embodied carbon in their projects.

One way or another, the battle for more electricity to accommodate rising demand is joined close to the ground.

This article was originally published on Forbes.com

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

Llewellyn King: Europeans fear what will happen as Putin asset Trump abandons them

Murderous tyrant and a fan at G20 meeting on June 28, 2019, in Osaka, Japan.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Europe is naked and afraid.

That was the message at a recent meeting of the U.K. Section of the Association of European Journalists (AEJ), at which I was an invited speaker.

It preceded a stark warning just over a week later from NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, also speaking in London, who said the danger from Vladimir Putin’s Russia won’t recede even if there is peace in Ukraine.

Rutte said defense spending must increase across Europe and recommended that it should reach 5 percent of GDP. Singling out Britain, he said if the Brits don’t do so, they should learn to speak Russian. He said Russia could overwhelm NATO by 2030.

The British journalists’ session reflected fear of Russia and astonishment at the United States. There was fear that Russia would invade the weaker states and that NATO had been neutered. Fear that the world’s most effective defense alliance, NATO, is no longer operational.

There was astonishment that America had abandoned its longstanding policies of support for Europe and preparedness to keep Russia in check. And there was disillusionment that President Trump would turn away from Ukraine in its war against Russian aggression.

The tone in Europe toward the United States isn’t one simply of anger or sorrow, but anger tinged with sorrow. Europeans see themselves as vulnerable in a way that hasn’t been true since the end of World War II.

They also are shattered by the change in America under Trump; his hostility to Europe, his tariffs and his preparedness to side with Russia. “How can this happen to America?” the British AEJ members asked me.

In many conversations, I found disbelief that America could do this to Europe, and that Trump should lean so far toward Putin. In Europe, where Putin has been an existential threat and where he invaded Ukraine, there is general amazement that Trump seems to crave the approbation of the Russian president.

Speaking to the journalists’ meeting via video from Romania, Edward Lucas, a former senior editor of The Economist, and now a columnist for The Times of London and a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy, said, “Donald Trump has turned the transatlantic relationship on its head. He wants to be friends with Vladimir Putin. We are in a bad mess.”

He said he saw no realistic possibility of a ceasefire in Ukraine in the near future, and he said Trump had made it clear that he was prepared to walk away from trying to bring peace “if it proved too hard.”

Lucas suggested that if European nations continue to back Ukraine after a Russian-dictated peace offer endorsed by America, Trump will punish them. He might do this by withdrawing U.S. assets from Europe, pulling back large numbers of troops from the 80,000 stationed there, and refusing to replace the American supreme commander of Europe.

“Then we will see how defenseless Europe is,” he said.

In Washington, it seems there is little understanding of the true weakness of Europe. No understanding that money alone won’t buy security for Europe.

Europe doesn’t have stand-off capacity, heavy airlift capacity, ultra-sophisticated electronic intelligence or anything approaching a defense infrastructure.

Trump has equated defense simply with money. But in Europe (although 27 of its nations are part of the European Union), there is no cohesive structure in place that could replace the role played by the United States.

Within the EU there are disagreements and there is the spoiler in the case of Hungary. Its pro-Russia ruler, Victor Orban, would like to try to block any concerted European action against Russia. The new right-wing Polish president’s hopes for good relations with Orban are a worry for most EU members.

I have long believed that there are three mutually exclusive views of Europe in the United States.

The first, favored by Trump and his MAGA allies, is that Europe is ripping off America in defense and through non-tariff trade barriers and is awash in expensive socialist systems embracing health, transportation and state nannying.

The second, favored by vacationers, is that Europe is a sort of Disney World for adults, as portrayed on PBS by Rick Steves’s travelogues: Watch the quaint people making wine or drinking beer.

The third is that Europe has been encouraged by successive administrations to accept the U.S. defense umbrella, as that favored America and its concerns, first about Soviet expansion and more recently about expansion under Putin.

Now Europe is alone in defense terms, naked and very afraid -- afraid of Trump’s pivot to Putin.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Trump Regime heavily Uses fear as its most potent Weapon

WARWICK, R.I.

Something new has entered American consciousness: fear of the state.

Not since the Red Scares (the first one followed the Russian Revolution and World War I, and the second followed World War II and the outbreak of the Cold War) has the state taken such an active role in political intervention.

The state under Donald Trump has an especial interest in political speech and action, singling out lawyers and law firms, universities and student activists, and journalists and their employers. It is certain that the undocumented live in fear night and day.

Fear of the state has entered the political process.

Presidents before Trump had their enemies. Nixon was famous for his “list” of mostly journalists. But his political paranoia was always there and it finally brought him down with the Watergate scandal,

Even John Kennedy, who had a soft spot for the Fourth Estate, took umbrage at the New York Herald Tribune and had that newspaper banned for a while from the White House.

Lyndon Johnson played games with and manipulated Congress to reward his allies and punish his enemies. With reporters it was an endless reward-and-punishment game, mostly achieved with information given or withheld.

The Trump administration is relentless in its desire to root out what it sees as state enemies, or those who simply disagree with it. They include the judicial system and all its components: judges, law firms and advocates for those whom it has disapproved of. If an individual lawyer so much as defends an opponent of the administration, that individual will be “investigated” which, in this climate, is a euphemism for persecuted.

If you are investigated, you face the full force of the state and its agencies. If you can find a lawyer of stature to defend you, you will be buried in debt, probably out of work and ruined without the “investigation” turning up any impropriety.

One mighty law firm, Paul, Weiss, faced with losing huge government contracts, bowed to Trump. It was a bad day for judicial independence.

The courts and individual judges are under attack, threatened with impeachment, even as the state seeks to evade their rulings.

Others are under threat and practice law cautiously when contentious matters arise. The price is known: Offend and be punished by loss of government work, by fear of investigation and by public humiliation by derision and accusation.

The boot of the state is poised above the neck of the universities.

If they allow free speech that doesn’t accord with the administration’s definition of that constitutional right, the boot will descend, as it did on Columbia.

Shamefully, to try to salvage $400 million in research funds, Columbia University caved. Speech on that campus is now circumscribed. Worse, the state is likely emboldened by its success.

Linda McMahon, the education secretary, has promised that with or without a Department of Education the administration will go after the universities and what they allow and what they teach, if it is antisemitic, as defined by the state, or if they are practicing diversity, equality and inclusion, a Trump irritant.

One notes that another university, Georgetown, is standing up to the pressure. Bravo!

At the White House, Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt has decided to usurp the White House Correspondents’ Association and determine herself who will cover the president in the reporters’ pool -- critical reporting in the Oval Office and on Air Force One.

Traveling with the president is important. That is how a reporter gets to know the chief executive up close and personal. A pool report from a MAGA blogger doesn’t cut it.

Trump has threatened to sue media outlets. If they are small and poor, as most of the new ones are, they can’t withstand the cost of defending themselves.

ABC, which is owned by Disney, caved to Trump even though its employees longed for the case to be settled in court. But corporate interests dictated accommodation with the state.

Accommodate they have and they will. Watch what happens with Trump’s $20 billion lawsuit against CBS’s 60Minutes. The truth is obvious, the result may be a tip of the hat to Trump.

Nowhere is fear more redolent, the state more pernicious and ruthless than in the deportation of immigrants without due process, without charges and without evidence. ICE says you are guilty and you go. Men wearing masks double you over, handcuff you behind your back and take you away, maybe to a prison in El Salvador.

Fear has arrived in America and can be felt in the marbled halls of the giant law firms, in newsrooms and executive offices, all the way to the crying children who see a parent dragged off by men in black, wearing balaclavas, presumably for the purpose of extra intimidation.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, as well as an international energy-sector consultant and speaker/ His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: Immigrants’ buoyancy, including success in science

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have been exploring the heights of scientific endeavor in reporting on artificial intelligence, from its use in medical research (especially promising) to its use in utilities and transportation. It is notable that many of the high achievers weren’t born here.

They have come here from everywhere, but the number of Asians is notable — and in that group, the number of women stands out.

As an immigrant, originally from what was called Rhodesia and is now called Zimbabwe, I am interested in why immigrants are so buoyant, so upwardly mobile in their adopted countries. I can distill it to two things: They came to succeed, and they mostly aren’t encumbered with the social limits of their upbringing and molded expectations. America is a clean slate when you first get here.

A friend from Serbia, who ascended the heights of academe and lectured at Tulane University, said his father told him, “Don’t go to America unless you want to succeed.”

A Korean mechanical engineer, who studied at American universities and now heads an engineering company that seeks to ease the electricity crisis, told me, “I want to try harder and do something for America. I chose to come here. I want to succeed, and I want America to succeed.”

When I sat at lunch in New York with an AI startup’s senior staff, we noticed that none of us was born an American. Two of the developers were born in India, one in Spain and me in Zimbabwe.

We started to talk about what made America a haven for good minds in science and engineering and we decided it was the magnet of opportunity, Ronald Reagan’s “shining city upon a hill.”

There was agreement from the startup scientists-engineers — I like the British word “boffins” for scientists and engineers taken together — that if that ever changes, if the anti-immigrant sentiment overwhelms good judgment, then the flow will stop, and the talented won’t come to America to pursue their dreams. They will go elsewhere or stay at home.

In the last several years, I have visited AI companies, interviewed many in that industry and at the great universities, such as Brown, UC Berkeley, MIT and Stanford, and companies such as Google and Nvidia. The one thing that stands out is how many of those at the forefront weren’t born in America or are first generation.

They come from all over the globe. But Asians are clearly a major force in the higher reaches of U.S. research.

At a AI conference, organized by the MIT Technology Review, the whole story of what is happening at the cutting-edge of AI was on view: faces from all over the world, new American faces. The number immigrants was awesome, notably from Asia. They were people from the upper tier of U.S. science and engineering confidently adding to the sum of the nation’s knowledge and wealth,

Consider the leaders of top U.S. tech companies who are immigrants: Microsoft, Satya Nadella (India); Google, Sundar Pichai (India); Tesla, Elon Musk (South Africa); and Nvidia, Jensen Huang (Taiwan). Of the top seven, only Apple’s Tim Cook, Facebook’s Jeff Zuckerberg and Amazon’s Andy Jassy can be said to be traditional Americans.

A cautionary tale: A talented computer engineer from Mexico with a family that might have been plucked from the cover of the Saturday Evening Post lived in the same building as I do. During the Trump administration, they went back to Mexico.

There had been some clerical error in his paperwork. But the humiliation of being treated as a criminal was such that rather than fight immigration bureaucracy, he and his family returned voluntarily to Mexico. America’s loss.

Every country that has had a large influx of migrants knows that they can bring with them much that is undesirable. From Britain to Germany to Australia, immigration has had a downside: drugs, crime and religions that make assimilation difficult.

But waves of immigrants have built America, from the Scandinavian and German wheat farmers that turned the prairies into a vast larder to Jews from Europe who moved to Hollywood in the 1930s and made America pre-eminent in entertainment, to today’s global wave that is redefining Yankee know-how in the world of neural networks and quantum computing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: What might happen if Google is broken up?

Google headquarters, in Mountain View, Calif.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google has few peers in the world of success. Founded on Sept. 4, 1998, it has a market capitalization of $1.98 trillion today.

It is global, envied, admired, and relied upon as the premier search engine. It is also hated. According to Google (yes, I googled it), it has 92 percent of the search business. Its name has entered English as a noun (google) and a verb (to google).

It has also swallowed so much of world’s advertising that it has been one of the chief instruments in the humbling and partial destruction of advertising-supported media, from local papers to the great names of publishing and television; all of which are suffering and many of which have failed, especially local radio and newspapers.

Google was the brainchild of two Stanford graduate students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. In the course of its short history, it has changed the world.

When it arrived, it began to sweep away existing search engines quite simply because it was better, more flexible, amazingly easy to use, and it could produce an answer from a few words of inquiry.

There were seven major search engines fighting for market share back then: Yahoo, Alta Vista, Excite, Lycos, WebCrawler, Ask Jeeves and Netscape. A dozen others were in the market.

Since its initial success, Google, like Amazon, its giant tech compatriot, has grown beyond all imagination.

Google has continued its expansion by relentlessly buying other tech companies. According to its own search engine, Google has bought 256 smaller high-tech companies.

The question is: Is this a good thing? Is Google’s strategy to find talent and great, new businesses or to squelch potential rivals?

My guess is some of each. It has acquired a lot of talent through acquisition, but a lot of promising companies and their nascent products and services may never reach their potential under Google. They will be lost in the corporate weeds.

In the course of its acquisition binge, Google has changed the nature of tech startups. When Google itself launched, it was a time when startup companies made people rich when they went public, once they proved their mettle in the market.

Now, there is a new financing dynamic for tech startups: Venture capitalists ask if Google will buy the startup. The public doesn’t get a chance for a killing. Innovators have become farm teams for the biggies.

Europe has been seething about Google for a long time, and there are ongoing moves to break up Google there. Here, things were quiescent until the Department of Justice and a bipartisan group of attorneys general brought suit against the company for monopolizing the advertising market. If the U.S. efforts to bring Microsoft to heal is any guide, the case will drag on for years and finally die.

History doesn’t offer much guidance as to what would happen if Google were to be broken up; the best example and biggest since the Standard Oil breakup in 1911 is AT&T in 1992.

In both cases, the constituent parts grew faster than the parent. The AT&T breakup fostered the Baby Bells — some, like Verizon, have grown enormously. Standard Oil was the same: The parts were bigger than the sum had been.

When companies have merged with the government’s approval, the results have seldom been the corporate nirvana prophesied by those urging the merger, usually bankers and lawyers.

Case in point: the 1997 merger of McDonnell Douglas and Boeing. Overnight the nation went from having two large airframe manufacturers to having just one, Boeing. The price of that is now in the headlines as Boeing, without domestic competition, has fallen into the slothful ways of a monopoly.

Antitrust action against Google has few lessons to be learned from the past. Computer-related technology is just too dynamic; it moves too fast for the past to illustrate the future. That would have been true at any time in the past 20 years (the years of Google’s ascent), but it is more so now with the arrival of artificial intelligence.

If the Justice Department succeeds, and Google is broken up after many years of litigation and possible legislation, it may be unrecognizable as the Google of today.

It is reasonable to speculate that Google at the time of a breakup may be many times its current size. Artificial intelligence is expected to bring a new surge of growth to the big tech companies, which may change search engines altogether.

Am I assuming that the mighty ship Google is too big to sink? It hasn’t been a leader to date in AI and is reportedly playing catch up.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: The wild and fabulous medical frontier with predictive AI

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When is a workplace at its happiest? I would submit that it is during the early stages of a project that is succeeding, whether it is a restaurant, an Internet startup or a laboratory that is making phenomenal progress in its field of inquiry.

There is a sustained ebullience in a lab when the researchers know that they are pushing back the frontiers of science, opening vistas of human possibility and reaping the extraordinary rewards that accompany just learning something big. There has been a special euphoria in science ever since Archimedes jumped out of his bath in ancient Greece, supposedly shouting, “Eureka!”

I had a sense of this excitement when interviewing two exceptional scientists, Marina Sirota and Alice Tang, at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), for the independent PBS television program White House Chronicle.

Sirota and Tang have published a seminal paper on the early detection of Alzheimer’s Disease — as much as 10 years before onset — with machine learning and artificial intelligence. The researchers were hugely excited by their findings and what their line of research will do for the early detection and avoidance of complex diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and many more.

It excited me — as someone who has been worried about the impact of AI on everything, from the integrity of elections to the loss of jobs — because the research at UCSF offers a clear example of the strides in medicine that are unfolding through computational science. “This time it’s different,” said Omar Hatamleh, who heads up AI for NASA at the Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Md.

In laboratories such as the one in San Francisco, human expectations are being revolutionized.

Sirota said, “At my lab …. the idea is to use both molecular data and clinical data [which is what you generate when you visit your doctor] and apply machine learning and artificial intelligence.”

Tang, who has just finished her PhD and is studying to be a medical doctor, explained, “It is the combination of diseases that allows our model to predict onset.”

In their study, Sirota and Tang found that osteoporosis is predictive of Alzheimer’s in women, highlighting the interplay between bone health and dementia risk.

The UCSF researchers used this approach to find predictive patterns from 5 million clinical patient records held by the university in its database. From these, there emerged a relationship between osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s, especially in women. This is important as two-thirds of Alzheimer’s sufferers are women.

The researchers cautioned that it isn’t axiomatic that osteoporosis leads to Alzheimer’s, but it is true in about 70 percent of cases. Also, they said they are critically aware of historical bias in available data — for example, that most of it is from white people in a particular social-economic class.

There are, Sirota and Tang said, contributory factors they found in Alzheimer’s. These include hypertension, vitamin D deficiency and heightened cholesterol. In men, erectile dysfunction and enlarged prostate are also predictive. These findings were published in “Nature Aging” early this year.

Predictive analysis has potential applications for many diseases. It will be possible to detect them well in advance of onset and, therefore, to develop therapies.

This kind of predictive analysis has been used to anticipate homelessness so that intervention – like rent assistance — can be applied before a family is thrown out on the street. Institutional charity is normally slow and often identifies at-risk people after a catastrophe has occurred.

AI is beginning to influence many aspects of the way we live, from telephoning a banker to utilities’ efforts to spot and control at-risk vegetation before a spark ignites a wildfire.

While the challenges of AI, from its wrongful use by authoritarian rulers and its menace in war and social control, are real, the uses just in medicine are awesome. In medicine, it is the beginning of a new time in human health, as the frontiers of disease are understood and pushed back as never before. Eureka! Eureka! Eureka!

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Dr. Yukie Nagai's predictive learning architecture for predicting sensorimotor signals.

— Dr. Yukie Nagai - https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2018.0030

Llewellyn King: How the move to a MAGA-style Britain flopped

Areas of the world that were part of the British Empire, with current British Overseas Territories underlined in red.

— Photo by RedStorm1368

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Make America Great Again.” Those words have been gently haunting me not because of their political-loading, but because they have been reminding me of something, like the snatches of a tune or a poem which isn’t fully remembered, but which drifts into your consciousness from time to time.

Then it came to me: It wasn’t the words, but the meaning; or, more precisely, the reasoning behind the meaning.

I grew up among the last embers of the British Empire, in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). I am often asked what it was like there.

All I can tell you is that it was like growing up in Britain, maybe in one of the nicer places in the Home Counties (those adjacent to London), but with some very African aspects and, of course, with the Africans themselves, whose land it was until Cecil John Rhodes and his British South Africa Company decided that it should be British; part of a dream that Britain would rule from Cape Town to Cairo.

Evelyn Waugh, the British author, said of Southern Rhodesia in 1937 that the settlers had a “morbid lack of curiosity” about the indigenous people. Although it was less heinous than it sounds, there was a lot of truth to that. They were there and now we were there; and it was how it was with two very different peoples on the same piece of land.

But by the 1950s, change was in the air. Britain came out of World War II less interested in its empire than it had ever been. In 1947, under the Labor government of Clement Attlee, which came to power after the wartime government of Winston Churchill, it relinquished control of the Indian subcontinent — now comprising India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

It was set to gradually withdraw from the rest of the world. The empire was to be renamed the Commonwealth and was to be a club of former possessions, often more semantically connected than united in other ways.

But the end of the empire wasn’t universally accepted, and it wasn’t accepted in the African colonies that had attracted British settlers, always referred to not as “whites” but as “Europeans.”

I can remember the mutterings and a widespread belief that the greatness that had put “Great” into the name Great Britain would return. The world map would remain with Britain's incredible holdings in Asia and Africa, colored for all time in red. People said things like the “British lion will awake, just you see.”

It was a hope that there would be a return to what were regarded as the glory days of the empire when Britain led the world militarily, politically, culturally, scientifically, and with what was deeply believed to be British exceptionalism.

That feeling, while nearly universal among colonials, wasn’t shared by the citizens back home in Britain. They differed from those in the colonies in that they were sick of war and were delighted by the social services which the Labor government had introduced, like universal healthcare, and weren’t rescinded by the second Churchill administration, which took power in 1951.

The empire was on its last legs and the declaration by Churchill in 1942, “I did not become the king’s first minister to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire,” was long forgotten. But not in the colonies and certainly not where I was. Our fathers had served in the war and were super-patriotic.

While in Britain they were experimenting with socialism and the trade unions were amassing power, and migration from the West indies had begun changing attitudes, in the colonies, belief flourished in what might now be called a movement to make Britain great again.

In London in 1954, it got an organization, the League of Empire Loyalists, which was more warmly embraced in the dwindling empire than it was in Britain. It was founded by an extreme conservative, Arthur K. Chesterton, who had had fascist sympathies before the war.

In Britain, the league attracted some extreme right-wing Conservative members of parliament but little public support. Where I was, it was quite simply the organization that was going to Make Britain Great Again.

It fizzled after a Conservative prime minister, Harold MacMillan, put an end to dreaming of the past. He said in a speech in South Africa that “winds of change” were blowing through Africa, though most settlers still believed in the return of empire.

It took the war of independence in Rhodesia to bring home MacMillan’s message. We weren’t going to Make Britain Great Again.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he based in Rhode Island.

whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: Three out-of-step environmental groups

Rachel Carson researching with Robert Hines on the New England coast in 1952. Her book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Greedy men and women are conspiring to wreck the environment just to enrich themselves.

It has been an unshakable left-wing belief for a long time. It has gained new vigor since The Washington Post revealed that Donald Trump has been trawling Big Oil for big money.

At a meeting at Mar-a-Lago, Trump is reported to have promised oil industry executives a free hand to drill willy-nilly across the country and up and down the coasts, and to roll back the Biden administration’s environmental policies. All this for $1 billion in contributions to his presidential campaign, according to The Post article.

Trump may believe that there is a vast constituency of energy company executives yearning to push pollution up the smokestack, to disturb the permafrost and to drain the wetlands, but he has gotten it wrong.

Someone should tell Trump that times have changed and very few American energy executives believe — as he has said he does — that global warming is a hoax.

Trump has set himself not only against a plethora of laws, but also against an ethic, an American ethic: the environmental ethic.

This ethic slowly entered the consciousness of the nation after the seminal publication of Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, in 1962.

Over time, concern for the environment has become an 11th Commandment. The cornerstone of a vast edifice of environmental law and regulation was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. It was promoted and signed by President Richard Nixon, hardly a wild-eyed lefty.

Some 30 years ago, Barry Worthington, the late executive director of the United States Energy Association, told me that the important thing to know about the energy-versus-environment debate was that a new generation of executives in oil companies and electric utilities were environmentalists; that the world had changed and the old arguments were losing their advocates.

“Not only are they very concerned about the environment, but they also have children who are very concerned,” Worthington told me.

Quite so then, more so now. The aberrant weather alone keeps the environment front-and-center.

This doesn’t mean that old-fashioned profit-lust has been replaced in corporate accommodation with the Green New Deal, or that the milk of human kindness is seeping from C-suites. But it does mean that the environment is an important part of corporate thinking and planning today. There is pressure both outside and within companies for that.

The days when oil companies played hardball by lavishing money on climate deniers on Capitol Hill and utilities employed consultants to find data that, they asserted, proved that coal use didn’t affect the environment are over. I was witness to the energy-versus-climate-and-environment struggle going back half a century. Things are absolutely different now.

Trump has promised to slash regulation, but industry doesn’t necessarily favor wholesale repeal of many laws. Often the very shape of the industries that Trump would seek to help has been determined by those regulations. For example, because of the fracking boom, the gas industry could reverse the flow of liquified-natural-gas at terminals, making us a net exporter not importer.

The United States is now, with or without regulation, the world’s largest oil producer. The electricity industry is well along in moving to renewables and making inroads on new storage technologies like advanced batteries. Electric utilities don’t want to be lured back to coal. Carbon capture and storage draws nearer.

Similarly, automakers are gearing up to produce more electric vehicles. They don’t want to exhume past business models. Laws and taxes favoring EVs are now assets to Detroit, building blocks to a new future.

As the climate crisis has evolved so have corporate attitudes. Yet there are those who either don’t or don’t want to believe that there has been a change of heart in energy industries. But there has.

Three organizations stand out as pushing old arguments, shibboleths from when coal was king, and oil was emperor.

These groups are:

The Sunrise Movement, a dedicated organization of young people that believes the old myths about big, bad oil and that American production is evil, drilling should stop, and the industry should be shut down. It fully embraces the Green New Deal — an impractical environmental agenda — and calls for a social utopia.

The 350 Organization is similar to the Sunrise Movement and has made much of what it sees as the environmental failures of the Biden administration — in particular, it feels that the administration has been soft on natural gas.

Finally, there is a throwback to the 1970s and 1980s: an anti-nuclear organization called Beyond Nuclear. It opposes everything to do with nuclear power even in the midst of the environmental crisis, highlighted by Sunrise Movement and the 350 Organization.

Beyond Nuclear is at war with Holtec International for its work in interim waste storage and in bringing the Palisades plant along Lake Michigan back to life. Its arguments are those of another time, hysterical and alarmist. The group doesn’t get that most old-time environmentalists are endorsing nuclear power.

As Barry Worthington told me: “We all wake up under the same sky.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: The trials of celebrity love, from Taylor-Burton to Swift-Kelce

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963)

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I wouldn’t know Taylor Swift if she sat next to me on an airplane, which is unlikely because she travels by private jet. If she were to take a commercial flight, she wouldn’t be sitting in the economy seats, which the airlines politely call coach.

Swift (who lives in Watch Hill, R.I., part of the time) needs to go by private jet these days: She is dating Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce, and that is a problem. Love needs candle-lightin,g not floodlighting.

Being in love when you are famous, especially if both the lovers are famous, is tough. The normal, simple joys of that happy state are a problem: There is no privacy, precious few places outside of gated homes where the lovers can be themselves.

They can’t do any of the things unfamous lovers take for granted, like catching a movie, holding hands or stealing a kiss in public without it being caught on video and transmitted on social media to billions of fans. Dinner for two in a cozy restaurant and what each orders is flashed around the world. “Oysters for you, sir?”

Worse, if the lovers are caught in public not doing any of those things and, say, staring into the middle distance looking glum, the same social media will erupt with speculation about the end of the affair.

If you are a single celebrity, you are gossip-bait, catnip for the paparazzi. If a couple, the speculation is whether it will be wedding bells or splitsville.

The world at large is convinced that celebrity lovers are somehow in a different place from the rest of us. It isn’t true, of course, but there we are: We think their highs are higher and lows are lower.

That is doubtful, but it is why we yearn to hear about the ups and downs of their romances; Swift’s more than most because they are the raw material of her lyrics. Break up with Swift and wait for the album.

When I was a young reporter in London in the 1960s, I did my share of celebrity chasing. Mostly, I found, the hunters were encouraged by their prey. But not when Cupid was afoot. Celebrity is narcotic except when the addiction is inconvenient because of a significant other.

In those days, the most famous woman in the world, and seen as the most beautiful, was Elizabeth Taylor. I was employed by a London newspaper to follow her and her lover, Richard Burton, around London. They were engaged in what was then, and maybe still is, the most famous love affair in the world.

The great beauty and the great Shakespearian actor were the stuff of legends. It also was a scandal because when they met in Rome, on the set of Cleopatra, they were both married to other people. She to the singer Eddie Fisher and he to his first wife, the Welsh actress and theater director Sybil Williams.

Social rules were tighter then and scandal had a real impact. This scandal, like most scandals of a sexual nature, raised consternation along with prurient curiosity.

My role at The Daily Sketch was to stake out the lovers where they were staying at the luxury Dorchester Hotel, on Park Lane.

I never saw Taylor and Burton. Day after day I would be sidetracked by the hotel’s public-relations officer with champagne and tidbits of gossip, while they escaped by a back entrance.

Then, one Sunday in East Dulwich, a leafy part of South London where I lived with my first wife, Doreen, one of the great London newspaper writers, I happened upon them.

Every Sunday, we went to the local pub for lunch, which included traditional English roast beef or lamb. It was a good pub — which today might be called a gastropub, but back then it was just a pub with a dining room. An enticing place.

One Sunday, we went as usual to the pub and were seated right next to my targets: the most famous lovers in the world, Taylor and Burton. The elusive lovers, the scandalous stars were there next to me: a gift to a celebrity reporter.

I had never seen before, nor in the many years since, two people so in love, so aglow, so entranced with each other, so oblivious to the rest of the room. No movie that they were to star in ever captured love as palpable as the aura that enwrapped Taylor and Burton. You could warm your hands on it. Doreen whispered from behind her hand, “Are you going to call the office?”

I looked at the lovers and shook my head. They were so happy, so beautiful, so in love I didn’t have the heart to break the spell.

I wasn’t sorry I didn’t call in a story then and I haven’t changed my mind.

Love in a gilded cage is tough. If Swift and Kelce are at the next table — unlikely -- in a restaurant, I will keep mum. Love conquers all.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Web site: whchronicle.co

Llewellyn King: The case for ‘hotter’ nuclear power in dealing with the electricity crunch