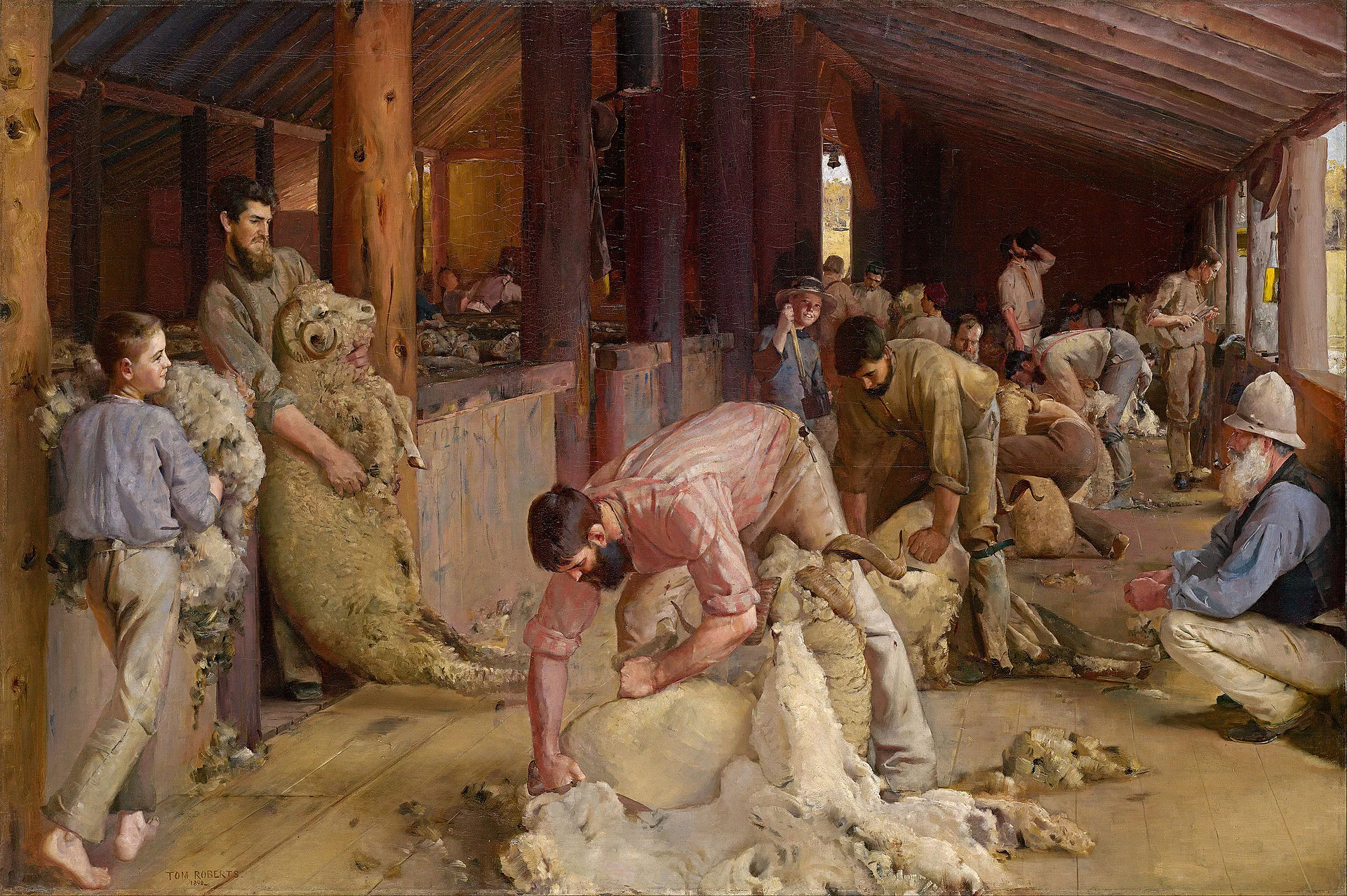

James P. Freeman: Bitcoin suckers ready to be sheared.

"Shearing the Rams,'' by Tom Roberts (1890).

“Faster than a speeding bullet.

More powerful than a locomotive.

Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.

Look! Up in the sky. It's a bird. It's a plane. It's…”

--Introduction to the television series The Adventures of Superman

… Bitcoin.

No stable currency -- digital or fiat -- rises by nearly 2,000 percent in a 12-month period. But that is exactly what bitcoin, the supersonically hyped, so-called digital currency, did in 2017. It opened at $997.69 in January then peaked at $19,343.04 in mid-December. And, within a 24-hour period, on the last trading day of the year, Ripple, another digital currency, rose by a staggering 30 percent. For delirious speculators -- as sound financiers fully comprehend -- cryptocurrency is kryptonite. Buyer and seller, beware. And government too.

Today, there are 1,370 recognized (and mostly unregulated) cryptocurrencies traded over one hundred exchanges with a total market capitalization (total market value) having appreciated to over $604 billion. Japan accounts for between a third and half of all global bitcoin trade, making it today’s biggest player. Bitcoin represents over 41 percent of the crypto market, making it the largest and most popular digital currency. At least today.

When it first began “trading” in July 2010 -- if that is the right description -- it was listed for six cents, according to Coindesk, an information services company for the digital asset and blockchain technology community. But you can now buy a sandwich at Subway or book a trip with expedia.com using bitcoin.

Sensibly, there is more debate about bitcoin than actual commerce.

Conceptually, digital currency or digital cash probably began in the late 1980s. But it wasn’t until Oct. 31, 2008 -- amid the global financial meltdown and The Great Recession -- that a white paper written by still-unknown author or authors, under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, gave the world cryptocurrency’s intellectual underpinning. But it lacked plausible financial underpinning. And still does.

Nonetheless, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” hatched a simple idea: “A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.” Crucially, without Internet technologies and other decentralizing innovations, bitcoin and its dueling alternatives (“alt-coins”) do not function. They are simply protocols. They are not currencies.

What the world needs now is not love. Instead, it needed, Nakamoto believed, “an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust.” A digital string of bits and bytes that supplants human nature. Well.

What emerged are mathematical formulas masquerading as currencies with no intrinsic value and no physical form.

In early 2009, the first bitcoin software was released, employing what is called “blockchain technology.” This allows digital information to be distributed but not copied. Through a web of computers these transactions (“broadcasts”) are ultimately validated and verified and then placed on a cloud ledger. Once verified, a given transaction is combined with other transactions to create a new block of data for the ledger. New blocks are added to the existing blocks in a way that is purportedly permanent and unalterable. All anonymously. And, supposedly, all securely. (Last year, hackers stole bitcoins worth (then) $65 million after attacking a major digital currency exchange (DCE).) In case of trouble you can’t call Interpol. Or Superman.

Theoretically, anything can be digitized, programmed and monitored. And there are obvious practical benefits in the new technology like verifying contracts and other records. But suddenly, like a blue-bolt of lightning appearing on a clear crisp day, without rhyme or reason, currencies were created out of these technical applications. Now, millions of people have created billions of dollars. Out of nothing. How fitting for the Millennial Generation. The Insta Generation. Instagram. Instacash.

Indeed, out of this irrational exuberance, (emphasis on the irrational) bitcoin.com claims that bitcoin is considered the “people’s money” born out of a “complex monetary system,” and based on “valid consent.” It relies upon the “consensus of math.” Furthermore, this nouveau financial utopia is “a stark contrast to the untrustworthy banking system we know of today.” Hence, bitcoin’s fantasy.

Some, with molten irony, call cryptocurrency the “next-gen gold.” The reasons for that analogy are two-fold: Bitcoins are virtually mined (in a computing resource-intensive process; nearly 10 U.S. households can be powered for one day by the electricity consumed for a single bitcoin transaction.) and, as the U.S. dollar replaced gold as the de-facto world’s reserve currency, some predict, likewise, a cryptocurrency will replace the U.S. dollar as the new reserve currency. Last month, Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs, decried the hostility to Bitcoin, saying it’s “not much different than gold.”

Mining bitcoin is difficult and intentional; miners use hard drives, not hardhats. Only 21 million bitcoins can be mined. Approximately 80 percent are already in “circulation.” And barring any unforeseen problems, the last coin to be mined will be in 2140. Then again, what could possibly go wrong with a new all-digital highly unregulated decentralized speculative global currency, where one must be conversant in mempools and satoshis?

Many believe bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are here to stay.

Adding a whiff of greater legitimacy to the whole enterprise, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, (CME) the world’s largest futures exchange, launched its own bitcoin futures contract on Dec. 17. Next June, Goldman Sachs expects to open a trading desk that would “make markets” in the cryptocurrencies.

New York University professor of corporate finance Aswath Damodaran last October argued in a blogpost that bitcoin is not an asset but was, in fact, “a currency, and as such, you cannot value it or invest in it. You can only price it and trade it.” (He also calls it “Gold for Millennials.”)

And tech investor James Altucher recently told CNBC, “This is the greatest tectonic shift in money and wealth that we will see in our lifetimes." Bitcoin, he says, “solves the problem of infinite money printing, forgery, double-spending and anonymity.” But Altucher also acknowledges that 98 percent of cryptocurrencies are scams.

There are, fortunately, healthy skeptics regarding the remaining 2 percent. The adults in the room (digital safe space?) come from academia, financial services and the government. Their thoughts are telling and cautionary.

One is Nobel Laureate and Columbia University Prof Joseph Stiglitz. Last month on Bloomberg TV he said bitcoin “ought to be outlawed.” Additionally, “bitcoin is successful only because of its potential for circumvention, lack of oversight.” Perhaps more damning, Stiglitz concluded, “It doesn’t serve any socially useful purpose.” And when asked if this phenomenon is “smoke and mirrors,” his reply was swift: “precisely.” He did speak, though, of the benefits of a “digital economy.”

The most outspoken critic is JPMorganChase Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon. In September he called bitcoin “a fraud.” He also takes exception with this kind of non-fiat cryptocurrency, but he thinks that a dollar-based cryptocurrency is workable. Recently, he said of cryptocurrency, “Governments are going to crush it one day.” In a statement earlier this month, Dimon said he was open-minded about the uses of cryptocurrencies “if properly controlled and regulated.”

Because of its latent anonymity, criminals can use bitcoin to effect drug trade and other illicit activity (ransomware and money laundering) without easily tracing such activity back to them. As Dimon alluded, it is surprising that there is not greater government oversight with respect to control over and, more importantly, taxation of cryptocurrencies.

Just before bitcoin hit its (for now) all-time high, current Fed Chair Janet Yellen, at a press conference in Washington, cited the financial stability risks from it as “limited.” Thus far, the U.S. banking system does not have “significant exposure” to any potential “threats” from bitcoin, she said. Notably, Yellen said that bitcoin is a “highly speculative asset” and underscored that it “doesn’t constitute legal tender.” Currently, bitcoin and all the other cryptocurrencies are not subject to regulation by the central bank. Last January Yellen, like many not stricken by the mania, did recognize blockchain as an “important technology.”

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan (he coined the phrase “irrational exuberance”) said in early December that bitcoin is “not a rational currency.” He likened bitcoin to the U.S. “Continental Currency,” introduced in 1775. It became worthless by 1782.

As for bitcoin in 2018, it might become the third massive asset bubble in this century, after the dot.com and housing bubbles, to burst in this young, disruptive century.

James P. Freeman is a former New York banker and now New England-based writer. This piece first appeared in New Boston Post, where he's a columnist. He's also a former columnist with The Cape Cod Times, His work has also appeared in The Providence Journal, newenglanddiary.com and the online service of the National Review.

Llewellyn King: A great 20th Century sex scandal; burning coal for bitcoin hoarding

Lewis Morley's 1963 portrait of Christine Keeler

A key player in one of the greatest sex scandals, Christine Keeler, died on Dec. 4.

When it comes to sex scandals, nothing that has been revealed lately has anything on Britain’s Profumo Scandal of the early 1960s. The cast was astounding: two nubile and very sexy young women, Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies; a society osteopath, Dr. Stephen Ward, who organized sex parties for men at the top; including the minister of war, John Profumo; a KGB officer at the Soviet Embassy, Yevgeny Ivanov, and Lord Astor, a leading aristocrat.

The set: Cliveden, Lord Astor’s famous country estate.

The unraveling: Christine’s two earlier lovers got into a fight and shots were fired outside of Ward’s home. Britain’s libel laws were very strict, and the extent of the sex scandal did not break in the newspapers until the rumors were published in the United States. The security services had already warned Profumo that he was sharing Christine with a Soviet spy, and he ended his affair with her.

The unforgivable factor: Profumo lied to the House of Commons and weeks later had to resign. He left the scene for social work in the East End of London, which he did for the rest of his life.

I met Christine and Mandy at the offices of The Sunday Mirror in 1963. My opinion: Christine was one of the most beautiful and intriguing women I have ever laid eyes on. She had a mystical quality, a Mona Lisa.

Mandy was less attractive, but bubbly and exuded fun. She was a good time-girl, who liked parties and sex by her own admission.

Christine averred these were her interests, too. But she was more: a beautiful, tragic child. She was just 19 and hoped to be model.

When it all came tumbling down, Ward was convicted of living off immoral earnings and committed suicide. Mandy married three times, lived in Israel and the United States, and was involved in the London theater. Christine began a huge and tragic slide that two marriages and two children failed to arrest. When she died, she was living in public housing; fat and raddled, all traces of her daunting beauty gone.

Lord Astor left England for the United States while the scandal cooled.

I always wished that Christine would have thrown her head of dark hair back and said, “I did it and I loved it.” Mandy more of less did.

Scandals don’t have happy endings, laced as they are with hypocrisy and betrayal. Everyone betrayed everyone in the Profumo Scandal. Christine was the most betrayed.

Unexpected consequence of bitcoin hoarding

The bitcoin fever — along with all of the other cryptocurrencies that blockchain technology has made possible — has one interesting consequence: a huge new demand for electricity.

Bitcoin miners, the operators who seek to create new entries and to verify the chain and both to make money and to protect from fraud, use staggering amounts of computing and staggering amounts of energy, including to cool the supercomputers.

But the electric bonanza won’t benefit all the electric utilities: The server farms follow the lowest cost for power. Therefore, electric companies with very cheap power, as those in the Northwest with hydropower, are the winners. But all the winners aren’t domestic: Some are likely to be abroad, and Iceland is a strong candidate to host the next rash of server farms.

Environmentalists are calling this a disaster. If cryptocurrency growth continues at its present wild speed, more electricity is likely to be generated with coal, especially outside of the United States.

It is the great growth area for electricity. While natural gas is becoming dominant in the United States, poor countries that want to jump on the high-tech bandwagon, like Poland, could be burning vast quantities of coal.

See it as the real-life consequences of something that only exists in cyberspace, a ghost materializing. The winner maybe Iceland with mega hydro available.

xxx

“Work is much more fun than fun.” — Noel Coward (1899-1973), English playwright, actor and composer.

Llewellyn King, a veteran publisher, columnist and international business consultant, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.