Bravo bottle bill, sort of

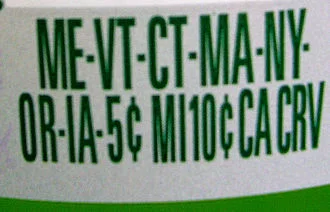

Deposit notice on a bottle sold in continental U.S. indicating the container's deposit value in various states; "CA CRV" means ''Cash Redemption Value.''

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com:

I was reading an article the other day about Connecticut’s ‘’bottle bill,’’ which mandates that when you buy a container of soda, water and beer, etc., you are charged 5 cents on top of the price of the container – a nickel that you get back when you return the container to a redemption center to be recycled. That’s a very effective law (which Rhode Island should have) because it helps reduces litter.

In the Nutmeg State, the bottle bill has become a bonanza for the state because there are so many too-busy or too-lazy people who just toss their containers in the trash or a recycling bin and don’t claim the nickel at redemption centers.

See this story from WNPR: http://wnpr.org/post/has-connecticuts-bottle-bill-changed-environmental-law-cash-cow

If you toss a can into your trash or recycling bin, instead of redeeming it for the 5- cent deposit -- your unclaimed nickel goes to the state with nothing to the private redemption centers that are charged with collecting the stuff in return for a slice of the nickel. That’s been happening more and more. Tough for these small businesses.

I have long wondered about the full environmental efficacy of recycling. How much of the value of recycling plastic, metal and plastic is offset by the energy and water (often hot) used to clean it up a bit before it goes into the recycling bin and to transport and process it? Still, again, recycling and bottle bills, discourage littering. Besides its demoralizing effects on the public, litter, especially the plastic stuff, kills some wildlife.

So bless bottle bills and recycling.

Tim Faulkner: Big money, confusion confront bottle-bill backers

By TIM FAULKNER/ecoRI News staff Expanding Massachusetts' existing bottle-redemption law to include bottled water, juices and other noncarbonated drinks seems like a simple proposition. But interviews with voters and business owners reveal that there is considerable confusion about what Question 2 will and won’t do.

The intent of Question 2 is to expand the 5-cent deposit program to include beverages that weren't around when the state's bottle bill began 32 years ago. This includes bottled water, fruit juices, teas and sports drinks. If approved by voters on Nov. 4, an expanded bottle bill would still exempt all milk containers and wine and liquor bottles. Juice boxes, juice pouches and infant formula also would be exempt.

Every five years, the 5-cent deposit would be indexed to inflation so that the financial incentive remains. A greater share of the deposit (3.5 cents) would go to redemption centers. The fee bottlers pay distributors and dealers for empties would increase to 3.5 cents. These fees would also be reviewed every five years to reflect inflation and the cost of doing business.

The expanded bill would restart the state's Clean Environmental Fund, which supports parks, air, water and forest programs.

What it doesn’t do. Question 2 will not change existing municipal recycling programs. If voters reject Question 2, the bottle bill stays the same.

Who supports the question? If there is an environmental group in the state that doesn’t support Question 2, ecoRI News didn't find it. Of the state's 351 municipalities, 209 have endorsed the referendum. Massachusetts Sierra Club is heavily involved, and MassPIRG is canvassing and making phone calls to voters.

The supporters' main argument is that an expanded bottle bill would reduce litter, send less waste to landfills, and generate funding for parks and clean-up projects. They estimate that 1.25 billion more bottles and cans will be recycled each year.

Proponents are framing the debate as a choice between “lies” from big soda companies and the people of Massachusetts who know better. They note that 80 percent of bottles and cans in the current deposit system get recycled, while only 23 percent of containers without a deposit are recycled, according to the Container Recycling Institute. They point to a Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) study that says an expanded program would save cities and towns $7 million annually in clean-up costs.

Who is against it? The “No” camp includes industry groups, grocery stores and big beverage corporations, all of which typically oppose new environmental regulations. Opponents include 7-Eleven, Coca-Cola, Nestlé Waters, Ocean Spray, Stop & Shop, the makers of Nantucket Nectars, the Retailers Association of Massachusetts, 21 chambers of commerce and 14 craft brewers.

The big money has come from the American Beverage Association, which represents small- and major-brand beverages, as well as bottlers and distributors. The association recently pumped $5 million into TV ads; Stop & Shop donated $300,000 to fight the question.

The opponents' main argument is that costs would go up for the entire beverage industry and the amount of red tape would increase.

Opponents are using antagonistic terms such as "forced deposit” and “forced redemption” to imply that changes would be a financial burden and an inconvenience foisted on them by government. One of the most controversial statements from the No on Question 2 campaign implies that 90 percent of the state already has municipal curbside recycling. Opponents claim an expanded program would be an expensive hassle, requiring new curbside containers at a cost of $60 million to cities and towns.

No on Question 2 didn't respond to repeated inquiries to verify these claims. According to the DEP, 47 percent of cities and towns offer curbside recycling, serving 64 percent of state residents.

Opponents also state that "Question 2 would raise your nickel deposit and additional fees every five years—without your vote." In reality, the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs would review the 5-cent deposit every five years and adjust it to stay current with inflation. Using the current inflation rate, the deposit would reach 10 cents in 2050.

In all, the claims that multinational beverage companies are behind the No on Question 2 initiative appear accurate, as most of the $8 million raised to stop the measure has come from outside the state. Proponents have raised $300,000, most of which came from the Massachusetts Sierra Club.

Mass. bottle use* 3.5 billion beverages are sold annually in Massachusetts.

Of those, 39 percent are non-carbonated and not covered by the bottle bill.

Water bottles account for 72 percent of the noncarbonated bottles.

983 million water bottles are sold in Massachusetts every year.

*Source: Container Recycling Institute.