Llewellyn King: Tech giants want in on electricity

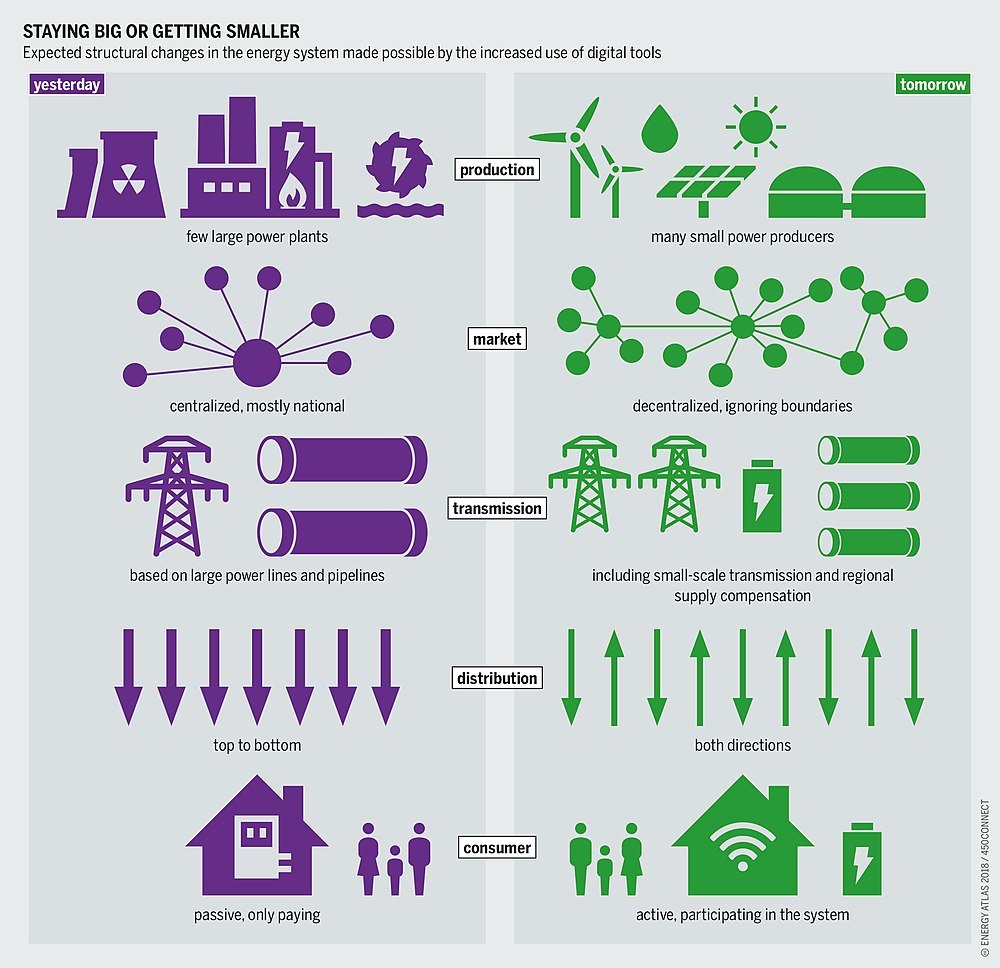

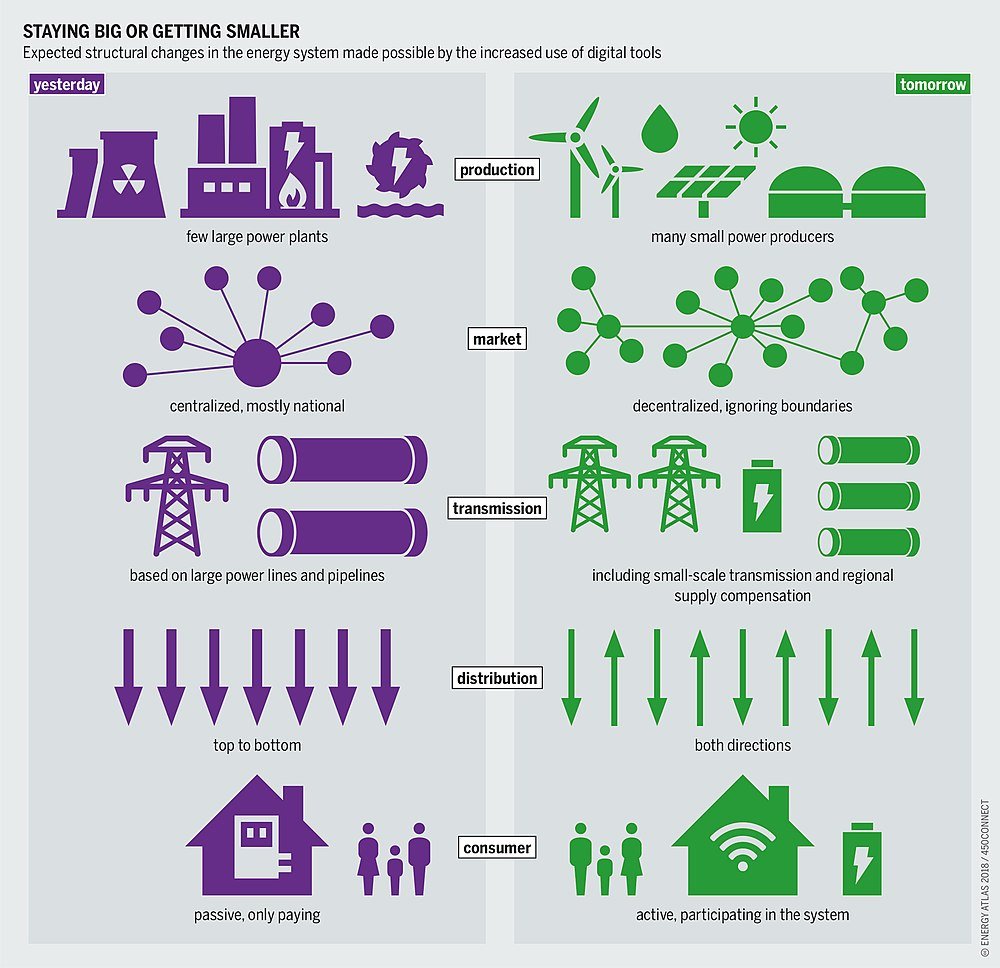

Centralized (left) vs. distributed electricity systems

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

During the desperate days of the energy crisis in the 1970s, it looked as though the shortage was permanent and we would have to change the way we lived, worked and played to allow for that.

In the end, technology solved the crisis.

For fossil fuels, it was 3D seismic, horizontal drilling and fracking. For electricity, it was wind and solar and better technology for making electricity with natural gas — a swing from burning it under boilers to burning it in aeroderivative turbines, essentially airplane engines on the ground.

A new energy shortage — this time confined to electricity — is in the making and there are a lot of people who think that, magically, the big tech companies, headed by Alphabet’s Google, will jump in and use their tech muscle to solve the crisis.

The fact is that the tech giants, including Google but also Amazon, Microsoft, Apple and Meta, are extremely interested in electricity because they depend on it supplies of it to their voracious data centers. The demand for electricity will increase exponentially as AI takes hold, according to many experts.

The tech giants are well aware of this and have been busy as collaborators and at times innovators in the electric space. They want to ensure an adequate supply of electricity, but also they insist that it be green and carbon-free.

Google has been a player in the energy field for some time with its Nest Renew service. This year, it stepped up its participation by merging with OhmConnect to form Renew Home. It is what its president, Ben Brown, and others call a virtual power plant (VPP). These are favored by environmentalists and utilities.

A VPP collects or saves energy from the system without requiring additional generation. It can be hooking up solar panels and domestic batteries, or plugging in and reversing the flow from an electric vehicle (EV) at night.

For Renew Home, the emphasis is definitely in the home, Brown told me in an interview.

Participants, for cash or other incentives (like rebates), cut their home consumption, managed by a smart meter, so that air conditioning can be put up a few notches, washing machines are turned off, and an EV can be reversed to feed the grid.

At present, Brown said, Renew Home controls about 3 gigawatts of residential energy use — a gigawatt is sometimes described as enough electricity to power San Francisco — and plans to expand that to 50 GW by 2030. All of it is already in the system and doesn't require new lines, power plants or infrastructure.

“We are hooking up millions of customers,” he said, adding that Renew Home is cooperating with 100 utilities.

Fortunately, peak demand and the ability to save on home consumption coincide between 5 p.m. and 9 p.m.

There is no question that more electricity will be needed as the nation electrifies its transportation and its manufacturing — and especially as AI takes hold across the board.

Todd Snitchler, president of the Electric Power Supply Association, told the annual meeting of the United States Energy Association that a web search using ChatGPT uses nine times as much power as a routine Google search.

Google, and the other four tech giants, are in the electricity-supply space, but not in the way people expect. Renew Home is an example; although Google’s name isn’t directly connected, it is the driving force behind Renew Home.

Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners (SIP), a development fund, financed largely by Google, has invested $100 million in Renew Home. Brown is a former Google executive as is Jonathan Winer, co-CEO and cofounder of SIP.

As Jim Robb, president of the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, the congressionally mandated, not-for-profit supply watchdog, told me recently on the TV show White House Chronicle, the expectation that Google will go out and build power plants is silly as they would face the same hurdles that electric utilities already face.

But Google is keenly interested in power supply, as are the other tech behemoths. The Economist reports they are talking to utilities and plant operators about partnering on new capacity.

Also, they are showing an interest in small modular reactors and are working with entrepreneurial power providers on building new capacity with the tech company taking the risk. Microsoft has signed a power-purchase agreement with Helion Energy, a fusion power developer.

Big tech is on the move in the electric space. It may even pull nuclear across the finish line.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Llewellyn King: As the electricity sector is reinvented, there's an urgent need for engineers and technicians to support them

At the new (founded 1997) but already highly prestigious Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have a soft spot for engineers and engineering. It started with my father. He called himself an engineer, even though he left school at 13 in a remote corner of Zimbabwe (then called Southern Rhodesia) and went to work in an auto repair shop.

By the time I remember his work clearly, in the 1950s, he was amazingly competent at everything he did, which was about everything that he could get to do. He could work a lathe, arc weld and acetylene weld, cut, rig, and screw.

My father used his imagination to solve problems, from finding a lost pump down a well to building a stand for a water tank that could supply several homes. He worked in steel: African termites wouldn’t allow wood to be used for external structures.

Electricity was a critical part of his sphere; installing and repairing electrical-power equipment was in his self-written brief.

Maybe that is why, for more than 50 years, I have found myself covering the electric-power industry. I have watched it struggle through the energy crisis and swing away from nuclear to coal, driven by popular feeling. I have watched natural gas, dismissed by the Carter administration as a “depleted resource,’’ roar back in the 1990s with new turbines, diminished regulation, and the vastly improved fracking technology.

Now, electricity is again a place of excitement. I have been to four important electricity conferences lately, and the word I hear everywhere about the challenges of the electricity future is “exciting.”

James Amato, vice president of Burns & McDonnell, a Kansas City, Mo.-based engineering, construction, and architecture firm that is heavily involved in all phases of the electric infrastructure, told me during an interview for the television program White House Chronicle that this is the most exciting time in supplying electricity since Thomas Edison set the whole thing in motion.

The industry, Amato explained, was in a state of complete reinvention. It must move off coal into renewables and prepare for a doubling or more of electricity demand by mid-century.

However, he also told me, “There is a major supply problem with engineers.” The colleges and universities aren’t producing enough of them, and not enough quality engineers — and he emphasized quality — are looking toward the ongoing electric revolution, which, to those involved in it, is so exhilarating and the place to be.

This problem is compounded by a wave of age retirements that is hitting the industry.

I believe that the electricity-supply system became a taken-for-granted undertaking and that talented engineers sought the glamor of the computer and defense industries.

Now, the big engineering companies are out to tell engineering school graduates that the big excitement is working on the world’s biggest machine: the U.S. electric supply system.

My late friend Ben Wattenberg, demographer, essayist, presidential speechwriter, television personality, and strategic thinker, hosted an important PBS documentary film and co-wrote a companion book, The First Measured Century: The Other Way of Looking at American History. He showed how our ability to measure changed public policy as we learned exactly about the distribution of people and who they were. Also, how we could measure things down to parts per billion in, say, water.

In my view, this is set to be the first engineered century, in tandem with being the first fully electric century. We are moving toward a new level of dependence on electricity and the myriad systems that support it. From the moment we wake, we are using electricity, and even as we sleep, electricity controls the temperature and time for us.

The new need to reduce carbon entering the atmosphere is to electrify almost everything else, primary transportation — from cars to commercial vehicles and eventually trains — but also heavy industrial uses, such as making steel and cement.

Amato said there is not only a shortage of college-educated engineers needed on the frontlines of the electric revolution but also a shortage of competent technicians or those trained in the crafts that support engineering. These are people who wield the tools, artisans across the board. In the electric utilities, there is also a need for line workers, a job that offers security, retirement, and esprit.

In the 1960s, the big engineering adventure was the space race. Today, it is the stuff that powers your coffeemaker in the morning, your cup of joe, or, you might say, your jolt of electrons.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: Readers should read about this Massachusetts-based company.

Llewellyn King: Get ready for blackouts and brownouts in the great energy transition

Electricity-transmission line in western Connecticut — a common scene in New England’s wooded areas.

Pole transformer. There’s a shortage of these things.

A perfect storm is gathering over the electric utility industry in the United States. It may break this year, next year or the year after, but break it will.

That is the consensus from utility executives I have been talking to over the past month. Several issues together amount to a clear danger of widespread blackouts and brownouts in the coming years. They come under the rubric of “transition.”

There are, in fact, two transitions stretching the electric utility industry. One is the climate imperative to turn from fossil fuels, primarily coal and natural gas with a smidgeon of oil, to renewables, almost totally wind and solar.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reckons that electricity from solar and wind will rise this year to 26 percent from 24 percent of national electricity, and that natural gas, the workhorse of the generation mix, will fall to 36 percent from 38 percent.The balance is dwindling coal use at 19 percent, and nuclear, hydro and geothermal generation making up the rest.

That leaves a significant need for new renewable generation: That is the first transition. It isn’t going as fast as the environmental lobby, or the Biden administration, would like, nor even as fast as the utilities would like. It has been substantially crimped by the supply chain tangle.

The American Public Power Association and the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association have been vocal about the shortage of pole transformers. The supply has dried up. Without transformers, new hookups are impossible and old ones are threatened if the transformers fail. The waiting list for something as simple as a bucket truck is three years.

Recent legislation has poured money at an unprecedented rate into the development of renewables, but none of it will help in the short term. It is a case of trying to force more of something into a bladder that is expanding too slowly and that can’t expand faster because of multiple restraints. A utility executive told me that the money is, if anything, making matters worse.

One of the things most concerning to the utilities is the fate of natural gas, both for its availability and price. Gas remains the principal go-to fuel for utilities. Many regard gas as a storage system even if they aren’t burning it to generate power daily.

Gas is special because it is relatively clean, it can be stored, and it can be installed in a short time at many locations. It doesn’t require trains, as does coal, and it works in any weather if the plants have been properly weatherized. Also, gas is very efficient to burn, so more of it can be transformed into electricity through so-called combined-cycle plants. It beats coal and nuclear hands down on the simplicity of the infrastructure it needs. Its efficiency is rated at about 64 percent versus 32 percent, or thereabouts, for coal.

Many utility executives believe that gas should be the primary way we store energy. They advocate maintaining a robust gas infrastructure so that it can come online quickly when needed and can run for as long as needed, unlike batteries.

But national gas policy is confusing. We want gas to be sent to Europe but not piped to New England, which may have an electricity deficit this winter, if not the next.

The second transition, working in tandem with the first, is electrification.

The United States is already headed toward a totally electrified transportation system, but heavy industry, like steel and cement, is also switching to electricity. Demand is showing the first signs of explosive growth. By 2050, demand will have more than doubled, according to many surveys.

While that alone is destabilizing, there is a wild card: the new unpredictable weather behavior.

This winter so far, we have had floods in California, freezing in Texas, tornadoes in the Midwest, and record snowfall in Buffalo. Add this to the other variables in electricity delivery, and you have a very troubling picture with such things as attacks on substations, cyberattacks and that pesky supply chain.

My advice: Keep spare batteries handy and a good supply of canned food. If you are sitting in the dark, you don’t want to be hungry.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Prepare for a messy electric revolution

An experimental Firefly electric helicopter, developed by famed Sikorsky Aircraft, based in Stratford, Conn.

In 2016, Solar Impulse 2 was the first solar-powered electric aircraft to complete a circumnavigation of the world.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The 21st Century is set to be The Electric Century. We are in the middle of a profound electrification binge that will leave its mark on every aspect of human endeavor.

I believed this before I attended the Edison Electric Institute annual meeting and convention in Orlando. Now I believe it more than ever. The institute is the trade association of the investor-owned utilities.

Civilization already has been running on electricity, but it will do so in a more complete way in future. In simple terms, what will happen is what hasn’t been electrified will be electrified. Manufacturing, mining, farming and the processing of everything, from grains to making concrete, will be electrified.

The first big shift -- the one we can all see and participate in -- is the electrification of transportation, total electrification. That will include aircraft in time, but light aircraft are already in the experimental phase.

You can see it with the plethora of electric vehicles coming to market from old marques but, more exciting, from new companies making everything from huge tractor-trailer trucks to snazzy new pickups and sedans.

Three of these were among a lineup of all-electric vehicles on display outside the JW Marriott, Grand Lakes, Orlando hotel:

· 2022 Lucid Air: A stunning beautiful sedan, and the MotorTrend Car of the Year, with an impressive range of 530 miles, and an equally impressive price of about $139,000.

· Rivian pickup: One of a range of all-electric pickup trucks; this one designed for lighter loads, but still boasting a towing capacity of 11,000 pounds.

· Freightliner eCascadia: A semi-truck with a load capacity of 82,000 pounds, but a range of only 230 miles.

The significant thing here is the number of new manufacturers. These mean new ideas, new visions, new materials, and new horizons.

Each huge advance in transportation has required new entrepreneurs -- otherwise, the car companies would have built the aircraft. It wasn’t Chrysler, General Motors and Ford that rose into the skies, but new names like Boeing, Douglas and Sikorsky.

Ultimately markets will decide, and markets aren’t welfare organizations. They are cruel judges and executioners as well as supremely generous patrons.

The driver for this revolution is climate change. Twenty years ago, you could still with some credibility debate its reality. Today, the evidence is in every weather forecast. Things are getting hotter and, as any science student will tell you, when stuff heats up, things happen.

The utility industry has embraced the rationale of change to modify and one day reverse climate change through curbing the volume of greenhouse gases going into the air. It starts with their own generation, and soon will embrace all the carbon that spews from boilers and tailpipes.

Revolutions are messy things. Once underway they get a life of their own. There is confusion and mistakes are made at the barricades. But once underway, they can’t be turned back; yesterday can’t be summoned rule tomorrow.

The utilities I spoke to feel they will be able to meet the new electric load demand with a mixture of leveling out the power from intermittent renewables. This is called DSM (demand side management) and uses data from smart-metering to manage the demand in collaboration with their customers. For example, incentivizing commercial firms to agree to shut down some operations during peak demand, and even to enter into agreements with homeowners to operate dishwashers and other appliances late at night.

Then there is using the transport fleet as a big battery. The theory is your new electric vehicle can feed back into the grid as needed when it is fully charged. But there are those who doubt that this will be enough to bridge the gap between generation and future demand. Andres Carvallo, one of the fathers of the smart grid, and a polymath who runs numbers on the future from his perch at Texas State University and his company, CMG Consulting, believes a lot more actual generation will be needed to meet the growth in electrification.

Presumably, much of this would come from the new small modular reactors. Here is a paradox. Utility executives say, to a person, that nuclear is needed, but none say how it will be bought, sited and built. When nuclear is talked up by utilities these days, there is a dream quality about it.

The great goal of the industry, or the revolution if you will, is zero emissions by mid-century. All embrace the electrification surge. Many utilities have plans to eliminate their own emissions, but none is ready for a huge, nationwide surge in demand, nor is there a national plan to deal with pressing impediments like a lack of transmission.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Don't burn it for electricity!

In Beartown State Forest, in The Berkshires

The Sandwich Range, in the White Mountain National Forest

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I like to sit by a crackling log fire as much as the next person. Indeed, we recently bought a backyard fire pit as a way to expand our winter living space in these times of pandemic claustrophobia. Even a lot of people burning logs in fire pits or fireplaces produce relatively minor pollution. It’s a compact, sensual, aesthetic experience.

Of course, with most fireplaces, having a fire loses your house more warmth than it gains, as it draws heat from the house up the chimney. Still, it’s very pleasant, if you can sit close enough to it.

In any event, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration is wrong to let wood-burning electric-power plants that now don’t meet state environmental standards get subsidies from rate payers. Yes, New England has lots of wood, but burning it in large quantities to generate electricity would mean much higher carbon emissions in the region, worsening global warning. Cutting down a lot more trees would obviously reduce forests’ ability to absorb carbon dioxide and emit oxygen, as well as harm wildlife and increase erosion by water.

Such clean-energy sources as solar, wind and geothermal are becoming cheaper and more efficient by the year. They’re the way to go. Burning wood to generate electricity is a terrible idea.

By the way, I remember that back in the days before Jiffy Pop and microwave stoves, how much fun it was to pop corn by putting the seeds in a screened frame over the fire and constantly shaking and flipping it. It took close attention but the popcorn you got seemed tastier than what you get now, or maybe that’s just misleading nostalgia. Of course, we soaked the product in butter and sprinkled on lots of salt: a slow-motion heart-disease developer.

xxx

Another sign that Massachusetts will continue to be a very rich state: Despite the pandemic and the national recession, it caused state tax revenues rose 8.8 percent in December from the year-earlier, pre-COVID month!