Charles Colgan: Warming seas are slamming coastal economies

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

Ocean-related tourism and recreation supports more than 320,000 jobs and US$13.5 billion in goods and services in Florida. But a swim in the ocean became much less attractive in the summer of 2023, when the water temperatures off Miami reached as high as 101 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 Celsius).

The future of some jobs and businesses across the ocean economy have also become less secure as the ocean warms and damage from storms, sea-level rise and marine heat waves increases.

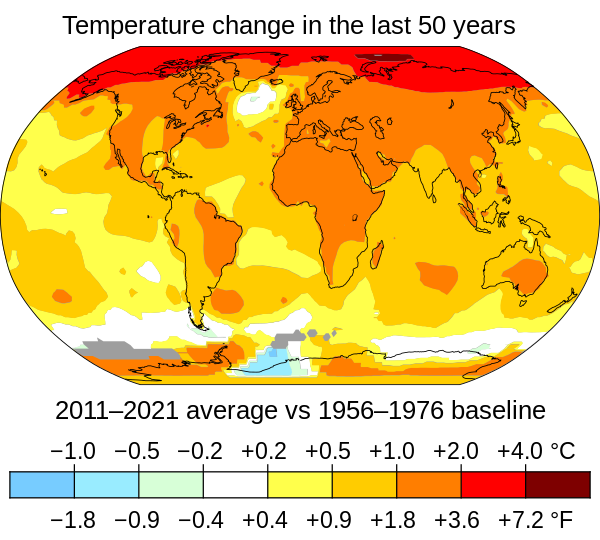

Ocean temperatures have been heating up over the past century, and hitting record highs for much of the past year, driven primarily by the rise in greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels. Scientists estimate that more than 90% of the excess heat produced by human activities has been taken up by the ocean.

That warming, hidden for years in data of interest only to oceanographers, is now having profound consequences for coastal economies around the world.

Understanding the role of the ocean in the economy is something I have been working on for more than 40 years, currently at the Center for the Blue Economy of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Mostly, I study the positive contributions of the ocean, but this has begun to change, sometimes dramatically. Climate change has made the ocean a threat to the economy in multiple ways.

The dangers of sea-level rise

One of the big threats to economies from ocean warming is sea-level rise. As water warms, it expands. Along with meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets, thermal expansion of the water has increased flooding in low-lying coastal areas and put the future of island nations at risk.

In the U.S., rising sea levels will soon overwhelm Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana and Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay.

Flooding at high tide, even on sunny days, is becoming increasingly common in places such as Miami Beach; Annapolis, Maryland; Norfolk, Virginia; and San Francisco. High-tide flooding has more than doubled since 2000 and is on track to triple by 2050 along the country’s coasts.

Satellite and tide gauge data show sea-level change from 1993 to 2020. National Climate Assessment 2023

Rising sea levels also push salt water into freshwater aquifers, from which water is drawn to support agriculture. The strawberry crop in coastal California is already being affected.

These effects are still small and highly localized. Much larger effects come with storms enhanced by sea level.

Higher sea level can worsen storm damage

Warmer ocean water fuels tropical storms. It’s one reason forecasters are warning of a busy 2024 hurricane season.

Tropical storms pick up moisture over warm water and transfer it to cooler areas. The warmer the water, the faster the storm can form, the quicker it can intensify and the longer it can last, resulting in destructive storms and heavy downpours that can flood cities even far from the coasts.

When these storms now come in on top of already higher sea levels, the waves and storm surge can dramatically increase coastal flooding.

What Hurricane Hugo’s flooding would look like in Charleston, S.C., with today’s higher sea levels.

Tropical cyclones caused more than $1.3 trillion in damage in the U.S. from 1980 to 2023, with an average cost of $22.8 billion per storm. Much of that cost has been absorbed by federal taxpayers.

It is not just tropical storms. Maine saw what can happen when a winter storm in January 2024 generated tides 5 feet above normal that filled coastal streets with seawater.

A winter storm that hit at high tide sent water rushing into streets in Portland, Maine, in January 2024.

What does that mean for the economy?

The possible future economic damages from sea-level rise are not known because the pace and extent of rising sea levels are unknown.

One estimate puts the costs from sea-level rise and storm surge alone at over $990 billion this century, with adaptation measures able to reduce this by only $100 billion. These estimates include direct property damage and damage to infrastructure such as transportation, water systems and ports. Not included are impacts on agriculture from saltwater intrusion into aquifers that support agriculture.

Marine heat waves leave fisheries in trouble

Rising ocean temperatures are also affecting marine life through extreme events, known as marine heat waves, and more gradual long-term shifts in temperature.

In spring 2024, one third of the global ocean was experiencing heat waves. Corals are struggling through their fourth global bleaching event on record as warm ocean temperatures cause them to expel the algae that live in their shells and give the corals color and provide food. While corals sometimes recover from bleaching, about half of the world’s coral reefs have died since 1950, and their future beyond the middle of this century is bleak.

Healthy coral reefs serve as fish nurseries and habitat. These schoolmaster snappers were spotted on Davey Crocker Reef near Islamorada in the Florida Keys. Jstuby/wikimedia, CC BY

Losing coral reefs is about more than their beauty. Coral reefs serve as nurseries and feeding grounds for thousands of species of fish. By NOAA’s estimate, about half of all federally managed fisheries, including snapper and grouper, rely on reefs at some point in their life cycle.

Warmer waters cause fish to migrate to cooler areas. This is particularly notable with species that like cold water, such as lobsters, which have been steadily migrating north to flee warming seas. Once-robust lobstering in southern New England has declined significantly.

How three fish and shellfish species migrated between 1974 and 2019 off the U.S. Atlantic Coast. Dots shows the annual average location. NOAA

In the Gulf of Alaska, rising temperatures almost wiped out the snow crabs, and a $270 million fishery had to be completely closed for two years. A major heat wave off the Pacific coast extended over several years in the 2010s and disrupted fishing from Alaska to Oregon.

This won’t turn around soon

The accumulated ocean heat and greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will continue to affect ocean temperatures for centuries, even if countries cut their greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 as hoped. So, while ocean temperatures fluctuate year to year, the overall trend is likely to continue upward for at least a century.

There is no cold-water tap that we can simply turn on to quickly return ocean temperatures to “normal,” so communities will have to adapt while the entire planet works to slow greenhouse gas emissions to protect ocean economies for the future.

Charles Colgan is director of Research for the Center for the Blue Economy at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Middlebury (Vt.)

Charles Colgan receives funding from several sources including NOAA and Lloyds of London. He was an author of the 5th National Climate Assessment chapter on oceans and the 4th California Climate Assessment chapter on coasts and oceans.

Llewellyn King: Why this is our decade of anxiety

“Anxiety” (1894), by Edvard Munch

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

They say that Generation Z is a generation of anxiety. Prima facie, I say they should get a grip. They are self-indulgent, self-absorbed and spoiled — just like every other generation.

Yet they reflect a much wider societal anxiety. It isn’t confined to those who are on the threshold of their lives.

I would highlight five causes of this anxiety:

The presidential election.

Global warming

Fear of wider war in Europe and the Middle East.

The impact of AI from job losses to the difficulty of knowing real from fake in everything.

The worsening housing shortage.

The election bears on all these issues. There is a feeling that the nation is headed for a train wreck no matter who wins.

Both President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump are known quantities. And there’s the rub.

Biden is an old man who has failed to convey strength either against Israeli Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu or the pro-Russian President Vladimir Putin movement in Congress.

He has led on climate change but failed to tell the story.

He has been unable to use the bully pulpit of his presidency and lay out, with clear and convincing rhetoric, where the nation should be headed and how he will lead it there.

And if his health should further deteriorate, there is the prospect of Vice President Kamala Harris taking over. She has distinguished herself by walking away from every assignment Biden has given her, in a cloud of giggles. She has no base, just Biden’s support.

Trump inspires that part of the electorate that makes up his base, many of them working people who have a sense of loss and disgruntlement. They really believe that this, the most unlikely man ever to climb the ramparts of American politics, will miraculously mend their world. More reprehensible are those members of the Republican Party who are scared of Trump, who have hitched their wagon to his star because they fear him, and love holding on to power at any price.

You will know them by their refusal to admit that the last election was honest and or to commit to accepting the result of the next election. In doing this, they are supporting a silent platform of insurrection.

The heat of summer has arrived early, and it is not the summer of our memories, of gentle winds, warm sun and wondrous beaches.

The sunshine of summer has turned into an ugly, frightening harbinger of a future climate that won’t support the life we have known. Before May was over, heat and related tornados took lives and spread destruction across Texas, the Mideast and the South.

I wonder about children who have to stay indoors all summer in parts of Texas, the South and West, where you can get burned by touching an automobile and where sports have to be played at dawn or after dusk. That should make us all anxious about climate change and about the strength and security of the electric grid as we depend more and more on 24/7 air conditioning.

The wars in Europe and the Middle East are troubling in new ways, ways beyond the carnage, the incalculable suffering, the buildings and homes fallen to bombs and shells.

Our belief that peace had come to Europe for all time has fallen. Surely as the Russians marched into Ukraine, they will march on unless they are stopped. Who will stop them? Isolation has a U.S. constituency it hasn’t had for 90 years.

In the Middle East, a war goes on, suffering is industrial and relentless in its awful volume, and the dangers of a wider conflict have grown exponentially. Will there ever be a durable peace?

Artificial intelligence is undermining our ability to contemplate the future. It is so vast in its possibilities, so unknown even to its aficionados and such a threat to jobs and veracity that it is like a frontier of old where people feared there were demons living. Employment will change, and the battle for the truth against the fake will be epic.

Finally, there is housing: the quiet crisis that saps expectations. There aren’t enough places to live in.

A nation that can’t house itself isn’t fulfilled. But the political class is so busy with its own housekeeping that it has lost sight of the need for housing solutions.

There are economic consequences that will be felt in time, the largest of which might be a loss of labor mobility — always one of the great U.S. strengths. We followed the jobs. Now we stay put, worried about shelter should we move.

This is ultimately the decade of anxiety, mostly because it is a decade in which we feel we are losing what we had. Time for us to get a grip.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

David Warsh: Why I hope that Biden decides, after all, not to run again

Confronting global warming is our greatest challenge.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What are the chances that Joe Biden will take himself out of the 2024 presidential campaign, perhaps with a Labor Day speech? Not good, based on what I read in the newspapers. Yet I have begun hoping that Biden just might drop out of the race. Here’s why.

It is not because Biden would fail to win re-election if he sticks to his plan to run. He promised to serve as a bridge and he has done that. His takeover of Donald Trump’s Big Talk platform of 2016 seems nearly complete. “Bidenomics,” which boils down to strategic rivalry with China, is the right road for American industry and trade for many years to come.

The problem is that a second term would almost certainly end in disaster, for both Biden and for the United States. The dismal war in Ukraine; the threat of another in Taiwan; the impending fiscal crises of America’s Social Security and medical-insurance programs: these are not problems for a good-hearted 82-year-old man of diminishing mental capacity, much less his fractious team of advisers.

Most of all, there is the challenge of global warming. It seems safe to say that there can no longer be doubt in any quarter that the problem is real. Perhaps this year’s strong demonstration effects were required to galvanize public opinion for action. But what action to take?

With respect to climate change, I’d written many times that the best introduction available is Spencer Weart’s 200-page book, The Discovery of Global Warming (Harvard, 2008.) Weart maintains a much more extensive hypertext version of the book on site of the Center for the History of Physics, which he founded in 1974. The digital edition was most recently updated in May 2023.

A distinguished historian of science, author of several books on other topics, including governance, Weart is a man of balanced and temperate views. Here is what he wrote in his book’s sobering “Conclusions: A Personal Statement:”

Policies put in place in recent decades to reduce emissions have made a real difference, bringing estimates of future temperatures down to a point where the risk of utterly catastrophic heating is now low. If we are lucky, and the planet responds at the lower limit of what seems possible, we might be able to halt the rise with less than another 1°C of warming, putting us a bit under 2°C above 19th-century temperatures. That would be a world with widespread devastation, but survivable as a civilization….

Yet the world’s scientists have explained that we need to get the emissions into a steep decline by the year 2030. Yes, that soon. What if we fail to turn this around? The greenhouse gases lingering in the atmosphere would lock in the warming. The policies we put in place in this decade will determine the state of the climate for the next 10,000 years….

If we do not make big changes in our economy and society, in how we live and how we govern ourselves, global warming will force far more radical changes upon us. In particular, we must restrain the influence of amoral corporations and extremely wealthy people, who have played a despicable role in blocking essential policies. To allow ever worse climate disruption would give those who already hold too much power opportunities to seize even more amid the chaos….

So, what to do about global warming? Negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine. Avoid war in Taiwan. Put the military-industrial complex on pause. Send Biden home to Wilmington, to nurture his family.

Throw open the race. Let other newspapers start writing stories like this one. Trust in the election to produce a young leader. American democracy has done it before. We don’t have four years to wait.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com

Llewellyn King: Rich nations must lead the way on the bumpy road to a green future

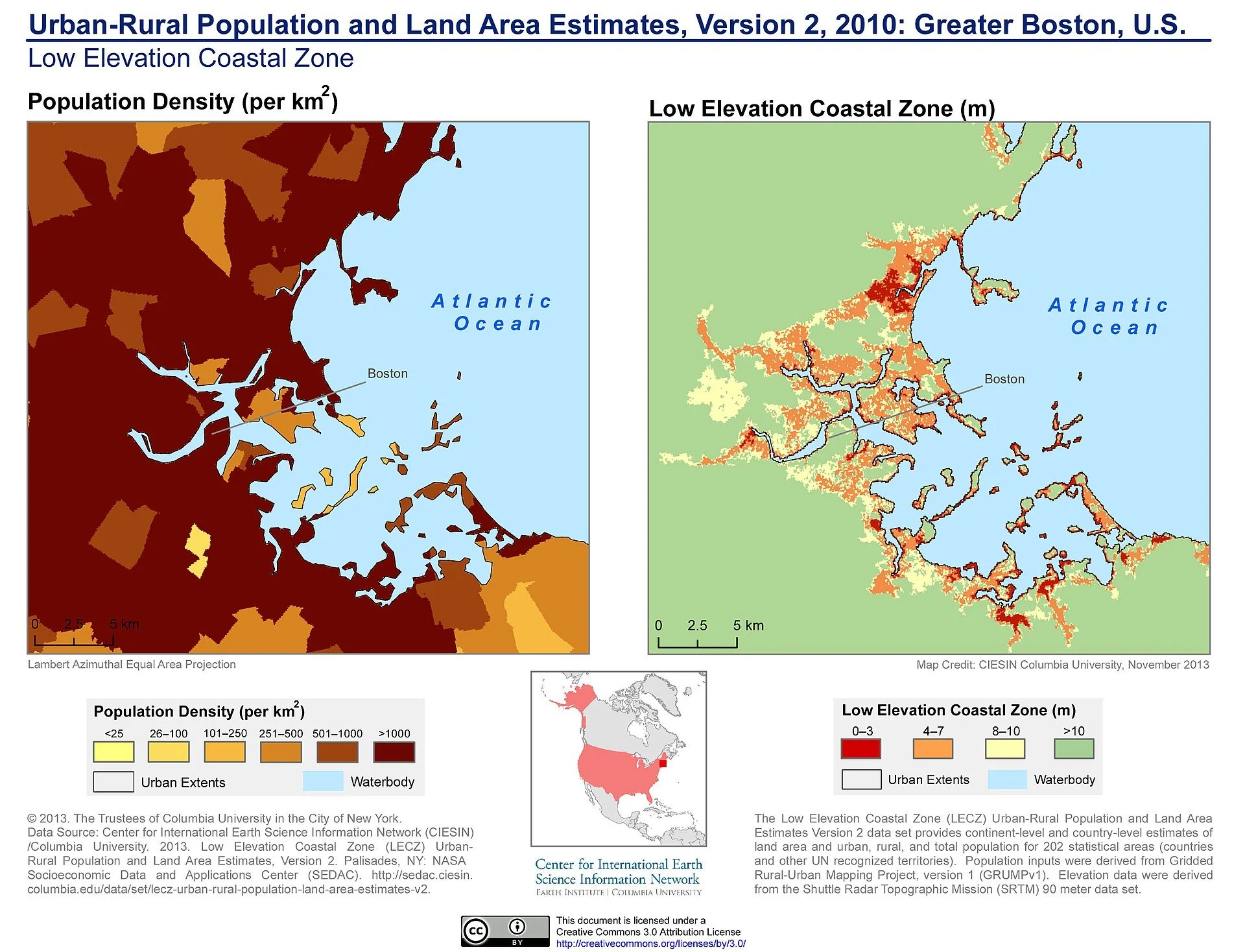

Rising seas caused by global warming threaten Greater Boston.

SEDACMaps - Urban-Rural Population and Land Area Estimates, v2, 2010: Greater Boston, U.S.

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates

I first heard about global warming being attributable to human activity about 50 years ago. Back then, it was just a curiosity, a matter of academic discussion. It didn’t engage the environmental movement, which marshaled opposition to nuclear and firmly advocated coal as an alternative.

Twenty years on, there was concern about global warming. I heard competing arguments about the threat at many locations, from Columbia University to the Aspen Institute. There was conflicting data from NASA and other federal entities. No action was proposed.

The issue might have crystallized earlier if it hadn’t been that between 1973 and 1989, the great concern was energy supply. The threat to humanity wasn’t the abundance of fossil fuels. It was the fear that there weren’t enough of them.

The solar and wind industries grew not as an alternative but rather as a substitution. Today, they are the alternative.

Now, the world faces a more fearsome future: global warming and all of its consequences. These are on view: sea-level rise, droughts, floods, extreme cold, excessive heat, severe out-of-season storms, fires, water shortages, and crop failures.

Sea-level rise affects the very existence of many small island nations, as the prime minister of Tonga, Siaosi Slavonia, made clear here at the annual assembly of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), an intergovernmental group with 167 member nations.

It also affects such densely populated countries as Bangladesh, where large, low-lying areas may be flooded, driving off people and destroying agricultural land. Salt works on food, not on food crops.

Sea-level rise threatens the U.S. coasts — the problem is most acute for such cities as Boston, New York, Miami, Charleston, Galveston and San Mateo. Flooding first, then submergence.

How does human catastrophe begin? Sometimes it is sudden and explosive, like an earthquake. Sometimes it advertises its arrival ahead of time. So it is with the Earth’s warming.

Delegates at the IRENA assembly felt that the bell of climate catastrophe tolls for their countries and their families. There was none of the disputations that normally attend climate discussions. Unity was a feature of this one.

The challenge was framed articulately and succinctly by John Kerry, U.S. special presidential envoy for climate. Kerry’s points:

—Global warming is real, and the evidence is everywhere.

—The world can’t reach its Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030 or the ultimate one of net-zero carbon by 2050 unless drastic action is taken.

—Warming won’t be reversed by economically weak countries but rather by rich ones, which are most responsible for it. Kerry said 120 less-developed countries produce only 1 percent of the greenhouse gases while the 20 richest produce 80 percent.

—Kerry, notably, declared that the technologies for climate remediation must come from the private sector. He wants business and private investment mobilized.

The emphasis at this assembly has been on wind, solar and green hydrogen. Wave power and geothermal have been mentioned mostly in passing. Nuclear got no hearing. This may be because it isn’t renewable technically. But it does offer the possibility for vast amounts of carbon-free electricity. It is classed as a “green” source by many government institutions and is now embraced by many environmentalists.

The fact that this conference has been held here is of more than passing interest. Prima facie, Abu Dhabi is striving to go green. It has made a huge solar commitment to the Al Dhafra project. When finished, it will be the world’s largest single solar facility. Abu Dhabi is also installing a few wind turbines.

Abu Dhabi has a four-unit nuclear power-plant at Barakah, with two 1,400-megawatt units online, one in testing and one under construction. Yet, the emirate is a major oil producer and is planning to expand its production from more than 3 million barrels daily to 5 million barrels.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has made oil more valuable, and even states preparing for a day when oil demand will drop are responding. Abu Dhabi isn’t alone in this seeming contradiction between purpose and practice. Green-conscious Britain is opening a new coal mine.

The energy transition has its challenges — even in the face of commitment and palpable need. The delegates who attended this all-round excellent conference will find that when they get home.

In the United States, utilities are grappling with the challenge of not destabilizing the grid while pressing ahead with renewables. Lights on, carbon out, is tricky.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. And he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

InsideSources

The wet look

Sunny day flooding in Miami during a “king tide’’.

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 2012.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The stuff below is a heavily edited version of some of the remarks I made in a talk a couple of weeks ago and seem to me particularly resonant as we head into summer coastal vacation season:

Most of us are in denial or oblivious when it comes to sea-level rise caused by global warming. For example, Freddie Mac researchers have found that properties directly exposed to projected sea-level rise have generally gotten no price discount compared to those that aren’t, though that may be changing. And some states don’t require sellers to disclose past coastal floods affecting properties for sale. Politicians often try to block flood-plain designations because they naturally fear that they would depress real-estate values.

So the coast keeps getting more built up, including places that may be underwater in a few decades. It often seems that everyone wants to live along the water.

As the near-certainty of major sea-level rise becomes more integrated into the pricing calculations of the real-estate sector, some people of a certain age can get bargains on property as long as they realize that the property they want to buy might be uninhabitable in 20 years. Younger people, however, should seek higher ground if they want to live near the ocean for a long time.

A tricky thing is that real estate can’t just be abandoned—it must pass from one owner to another. Some local governments’ coastal permits require owners to pay to remove their structures when the average sea level rises to a certain point. Absent such requirements, many local governments’ budgets may not be enough to pay for demolition or the moving costs associated with inundation. There are some interesting liability issues here.

What to do?

Administrative mitigation would include raising federal flood-insurance rates and more frequently updating flood-projection maps. More localities can take stronger steps to ban or sharply limit new structures in flood-prone areas and/or order them removed from those areas. And, as implied above, they should implement flood-experience-and-projection disclosure requirements in sales documents.

As for physical answers to thwarting the worst effects of sea-level rise, especially in urban areas, many experts believe that some form of the Dutch polder approach, which integrates hard stone, concrete or even metal infrastructure, and soft nature-based infrastructure, along with dikes, drainage canals and pumps, may have to be applied in some low places, such as Miami and Boston’s Seaport District. Barrington and Warren, R.I., look like polder country.

Polders are large land-and-water areas, with thick water-absorbent vegetation, surrounded by dikes, where the ground elevation is below mean sea level and engineers control the water table within the polder.

Just hardening the immediate shoreline, and especially beaches, with such structures as stone embankments to try to keep out the water won’t work well. That just makes the water push the sand elsewhere and can dramatically increase shoreline erosion.

On the other hand, creating so-called horizontal levees – with a marshy or other soft buffering area backed with a hard surface -- can be a reasonable approach to reduce the impact of storms’ flooding on top of sea-level rise.

Certainly establishing marshes (and mangrove swamps in tropical and semi-tropical coastal communities) can reduce tidal flooding and the damage from storm waves, but that may be a political nonstarter in some fancy coastal summer- or winter-resort places. Then there’s putting more houses and even stores and other nonresidential buildings on stilts, though that often means keeping buildings where safety considerations would suggest that there shouldn’t be any structures, such as on many barrier beaches. Still, it would be amusing to see entire large towns on stilts. Good water views.

Oyster and other shellfish beds can be developed as (partly edible!) breakwaters. And laying down permeable road and parking lot pavements can help sop up the water that pours onto the land. I got interested in how shellfish beds can act as a brake on flood damage while editing a book about Maine aquaculture last year. Of course, the hilly coast of Maine provides many more opportunities to enjoy a water view even with sea-level rise while staying dry than does, say, South County’s barrier beaches.

In more and more places where sea-level rise has caused increasing ‘’sunny day flooding’’ -- i.e., without storms -- streets are being raised.

I’m afraid that, barring, say, a volcanic eruption that rapidly cools the earth, slowing the sea-level rise, the fact is that we’ll have to simply abandon much of our thickly developed immediate coastline and move our structures to higher ground.

Working-waterfront enterprises -- e.g., fishing and shipping -- must stay as close to the water as possible. But many houses, condos, hotels, resorts and so on can and should be moved in the next few years. If they don’t have to be on a low-lying shoreline, they shouldn’t be there as sea level rises. For that matter, entire large communities may have to be entirely abandoned to the sea even in the lifetime of some people here.

Coastal communities and property owners face hard choices: whether to try to hold back the rising ocean or to move to higher ground. Nothing can prevent this situation from being expensive and disruptive.

Common sense would suggest that we not build where it floods and that we should stop recycling flooded properties. Again, flood risks should be fully disclosed and we need to protect or restore ecologies, such as marshes, shellfish and coral reefs and dune grass, that reduce flooding and coastal erosion.

Nature wins in the end.

Higher and higher

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Shoreline access continues to be a stormy issue in Rhode Island and some other coastal states. There’s constant conflict that pits beach walkers, swimmers and sitters from the general public against generally affluent shoreline house owners, who have taken over more and more of the New England coast, with many striving mightily to keep the public as far away from their houses as they can. Understandable!

There’s a measure in the Rhode Island House that attempts to end the old confusions about how high on a beach the public can go without being legally kicked off by irritated owners. (“We paid a lot of money for this place!”) It states that folks can go 10 feet landward beyond a “recognizable high tide line.’’ That’s defined as the mark left “upon tide flats, beaches, or along shore objects that indicates the intersection of the land with the water’s surface level at the maximum height reached by a rising tide.’’ (Lawyerly poetry!) That would often, but presumably not always, mean a line of seaweed, oil, shells or other debris.

None of this means that you could legally climb up the wall in front of someone’s house, whatever passes for the high-water mark.

A not very helpful 1982 state Supreme Court ruling said that the mean high-water mark is the appropriate boundary between the shoreline to which the public has access and private property, but the court said that determining the line requires “special surveying equipment and expertise.’’ What with the changes wrought by waves and storms, it can be mighty hard to find the high-tide mark in any case. Confused and/or nervous beach visitors would thus tend to move down to the low-tide mark (also not always easy to define). The new legislation doesn’t seem on the face of it to make things much easier for beach walkers to follow. And where can beach strollers sit down without being yelled at?

Inevitably, a shadowy group, with the windy title of “Shoreline Taxpayers for Respectful Traverse, Environmental Responsibility and Safety,’’ representing affluent owners, plans to fight the measure with lawsuits. Since the rich generally run America, I’d bet they’ll win; and I suspect that most of the group’s clients are from out of state.

(Some members of this same crowd also try to stop the sand from washing away in front of their houses by putting up hard barriers to catch and hold it. But that just ends up depriving the shores further down the shore of sand. Indeed, it worsens erosion.)

But wait! Rising seas caused by manmade global warming may make this issue more wrought. Estimates are that sea level will rise by almost a foot between now and 2050, and there will be more and worse hurricanes and other storms. That would push the high-tide mark (or marks), and the strolling public, further landward, toward those beach houses.

For that matter, it will also force some landowners to eventually abandon their houses, many of which shouldn’t have been put there in the first place, let alone subsidized by taxpayers through federal flood insurance and frequent repairs to beach roads by states and municipalities. Indeed, permanently removing structures from stretches of the immediate shore will be a rapidly increasing phenomenon in the next few decades. Sad. Most people love being close to the water, as real-estate prices suggest.

Will the Feds be buying out a lot of these properties through the Federal Emergency Management Agency?

Before the rise of the shoreline summer house, spawned by the money from the Industrial Revolution, few people in New England coastal communities built houses right along the shore. It was considered too insecure in the face of storms and flooding. Houses were built much higher up. So you can see that the oldest buildings in New England coastal towns are in village centers or associated with now mostly gone farms.

Part of my family has long lived in Falmouth, on Cape Cod. Some of their 18th and 19th Century houses are still standing near the town green. These people were in farming, boat building, fishing and assorted other trades. On the other hand, most of the houses around the harbors and along the beaches of the town date from the 1870’s and later, when they were built as summer places after the extension of the railroad brought affluent people, including some of my other ancestors, from the Boston area to summer on the Cape. This sort of movement was replicated on coasts, including the Great Lakes, around America.

Occasionally hurricanes or other big storms would damage or destroy the houses, but the owners would usually have enough money and/or insurance (including in the past few decades federal flood insurance) to rebuild in exactly the same insecure places.

In any event, with rapidly rising seas, that can’t go on. Let the great trek inland begin (if only a few dozen yards).

Melissa Bailey: West Nile Virus loves global warming

Global distribution of the West Nile Virus. There have been many cases in southern New England.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health.

—Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public health school.

Michael Keasling, of Lakewood, Colo., was an electrician who loved big trucks, fast cars and Harley-Davidsons. He’d struggled with diabetes since he was a teenager, needing a kidney transplant from his sister to stay alive. He was already quite sick in August when he contracted West Nile Virus after being bitten by an infected mosquito.

Keasling spent three months in hospitals and rehab, then died on Nov. 11 at age 57 from complications of West Nile Virus and diabetes, according to his mother, Karen Freeman. She said she misses him terribly.

“I don’t think I can bear this,” Freeman said shortly after he died.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread West Nile through Colorado last year, experts said. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections — those linked to serious illness such as meningitis or encephalitis — in Colorado in 2021, the highest numbers in 18 years.

The rise in cases may be a sign of what’s to come: As climate change brings more drought and pushes temperatures toward what is termed the “Goldilocks zone” for mosquitoes — not too hot, not too cold — scientists expect West Nile transmission to increase across the country.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health, said Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public-health school.

Although most West Nile infections are mild, the virus is neuroinvasive in about 1 in 150 cases, causing serious illness that can lead to swelling in the brain or spinal cord, paralysis, or death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People older than 50 and transplant patients like Keasling are at higher risk.

Over the past decade, the U.S. has seen an average of about 1,300 neuroinvasive West Nile cases each year. Basu saw his first one in Massachusetts several years ago, a 71-year-old patient who had swelling in his brain and severe cognitive impairment.

“That really brought home for me the human toll of mosquito-borne illnesses and made me reflect a lot upon the ways in which a warming planet will redistribute infectious diseases,” Basu said.

A rise in emerging infectious diseases “is one of our greatest challenges” globally, the result of increased human interaction with wildlife and “climatic changes creating new disease transmission patterns,” said a major United Nations climate report released Feb. 28. Changes in climate have already been identified as drivers of West Nile infections in southeastern Europe, the report noted.

The relationship between lack of rainfall and West Nile Virus is counterintuitive, said Sara Paull, a disease ecologist at the National Ecological Observatory Network in Boulder, Colo., who studied connections between climate factors and West Nile in the U.S. as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of California-Santa Cruz.

“The thing that was most important across the nation was drought,” she said. As drought intensifies, the percentage of infected mosquitoes goes up, she found in a 2017 study.

Why does drought matter? It has to do with birds, Paull said, since mosquitoes pick up the virus from infected birds before spreading it to humans. When the water supply is limited, birds congregate in greater numbers around water sources, making them easier targets for mosquitoes. Drought also may reduce bird reproduction, increasing the ratio of mosquitoes to birds and making each bird more vulnerable to bites and infection, Paull said. And research shows that when their stress hormones are elevated, birds are more likely to get infectious viral loads of West Nile.

A single year’s rise in cases can’t be attributed to climate change, since cases naturally fluctuate by year, in part due to cycles of immunity in humans and birds, Paull said. But we can expect cases to rise with climate change, she found.

Increased drought could nearly double the number of annual neuroinvasive West Nile cases across the country by the mid-21st Century, and triple it in areas of low human immunity, Paull’s research projected, compared with averages from 1999 to 2013.

Drought has become a major problem in the West. The Southwest endured an “unyielding, unprecedented, and costly drought” from January 2020 through August 2021, with the lowest precipitation on record since 1895 and the third-hottest daily average temperatures in that period, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report found.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread the West Nile virus throughout Colorado last year. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections in Colorado ― the highest numbers in 18 years.

“Exceptionally warm temperatures from human-caused warming” have made the Southwest more arid, and warm temperatures and drought will continue and increase without serious reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the report said.

Ecologist Marta Shocket has studied how climate change may affect another important factor: the Goldilocks temperature. That’s the sweet spot at which it’s easiest for mosquitoes to spread a virus. For the three species of Culex mosquitoes that spread West Nile in North America, the Goldilocks temperature is 75 degrees Fahrenheit, Shocket found in her post-doctoral research at Stanford University and UCLA. It’s measured by the average temperature over the course of one day.

“Temperature has a really big impact on the way that mosquito-transmitted diseases are spread because mosquitoes are cold-blooded,” Shocket said. The outdoor temperature affects their metabolic rate, which “changes how fast they grow, how long they live, how frequently they bite people to get a meal. And all of those things impact the rate at which the disease is transmitted,” she said.

In a 2020 paper, Shocket found that 70 percent of people in the U.S. live in places where average summer temperatures are below the Goldilocks temperature, based on averages from 2001 to 2016. Climate change is expected to change that.

“We would expect West Nile transmission to increase in those areas as temperatures rise,” she said. “Overall, the effect of climate change on temperature should increase West Nile transmission across the U.S. even though it’s decreasing it in some places and increasing it and others.”

Janet McAllister, a research entomologist with the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, in Fort Collins, Colo., said climate change-influenced factors like drought could put people at greater risk for West Nile, but she cautioned against making firm predictions, since many factors are at play, including bird immunity.

Birds, mosquitoes, humans and the virus itself may adapt over time, she said. For instance, hotter temperatures may drive humans to spend more time indoors with air conditioning and less time outside getting bitten by insects, she said.

Climate factors like rainfall are complex, McAllister added: While mosquitoes do need water to breed, heavy rain can flush out breeding sites. And because the Culex mosquitoes that spread the virus live close to humans, they can usually get enough water from humans’ sprinklers and birdbaths to breed, even during a dry spring.

West Nile is preventable, she noted: The CDC suggests limiting outdoor activity during dusk and dawn, wearing long sleeves and bug repellent, repairing window screens, and draining standing water from places like birdbaths and discarded tires. Some local authorities also spray larvicide and insecticide.

“People have a role to play in protecting themselves from West Nile Virus,” McAllister said.

In the Denver suburbs, Freeman, 75, said she doesn’t know where her son got infected.

“The only thing I can think of, he has a house, they have a little baby swimming pool for the dogs to drink out of,” she said. “So maybe the mosquitoes were around that, I don’t know.”

Melissa Bailey is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Roger Warburton: Nearby ocean warming a climate-change warning for New England

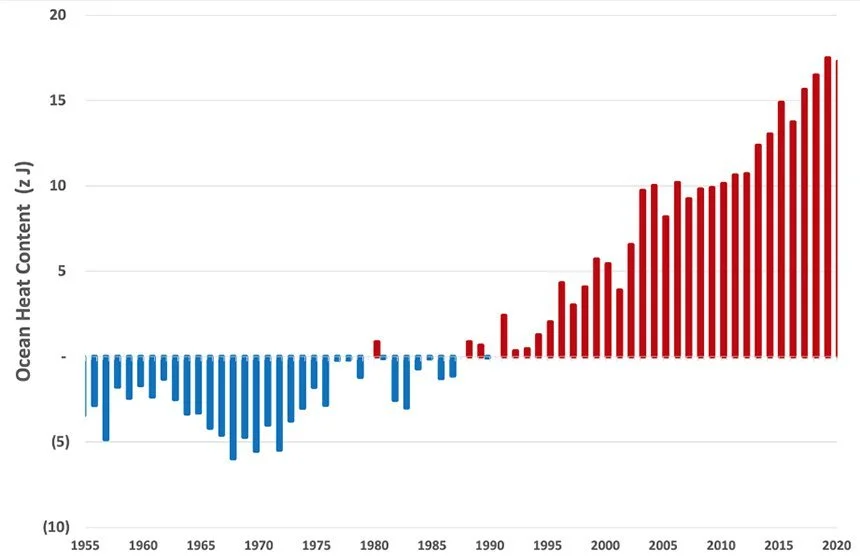

The changes in heat content of the top 700 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2020.

— Chart by Roger Warburton/NCEI and NOAA

New England’s historical and cultural identity is inextricably linked to the ocean that laps at nearly 6,200 miles of coastline. And the region’s ocean waters are warming, and not just a little.

The above chart shows just how much the ocean has warmed over the past 65 years and, due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases, the heat dumped into the ocean has doubled since 1993. It is even more concerning that ocean warming has accelerated since 2010.

The world’s oceans, in 2021, were the hottest ever recorded by humans.

The findings of the data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), have been confirmed by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

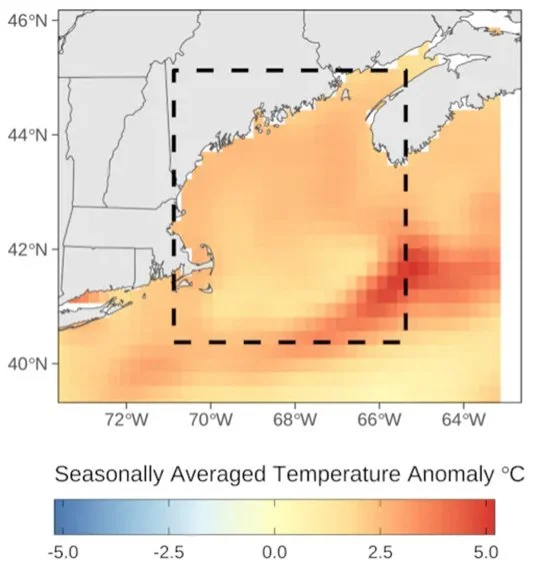

The news for New England is worse, as the ocean here is heating up faster than that of the rest of the world.

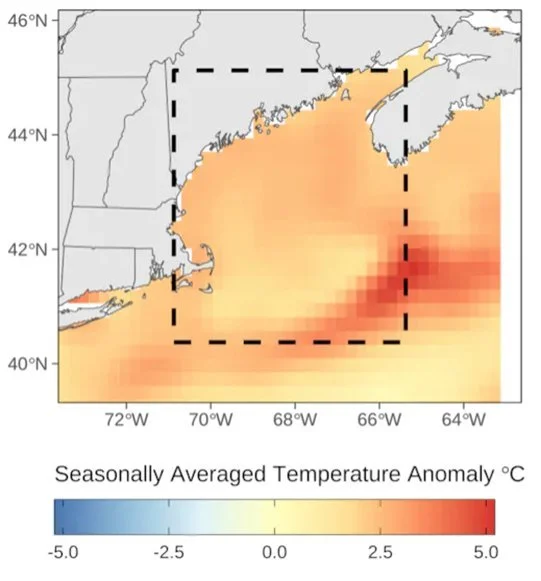

This map illustrates the seasonally averaged sea-surface temperature anomaly in the Gulf of Maine.

—Gulf of Maine Research Institute

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced that between September and November of last year, the warmth of inlet waters adjacent to Maine and northern Massachusetts was the highest on record.

“This year [the Gulf of Maine] was exceptionally warm,” said Kathy Mills, who runs the Integrated Systems Ecology laboratory at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. “I was very surprised.”

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 96 percent of the world’s oceans, increasing at a rate of 0.1 degrees Celsius (0.18 degrees Fahrenheit) annually over the past four decades.

The increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere traps heat in the air. The air in contact with the ocean transfers heat to the ocean, increasing what is called the ocean heat content (OHC).

The first measurements of ocean data were taken on Capt. James Cook’s second voyage (1772-1775). Although not very accurate, those measurements were among the first instances of oceanographic data recorded and preserved.

Today, ocean measurements are taken by a variety of modern instruments deployed from ships, airplanes, satellites and, more recently, underwater robots. A 2013 study by John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, contains an interesting historical overview of ocean measurements.

Abraham’s study used data from new instruments, such as expendable bathythermographs and Argo floats. The Argo program is an array of more than 3,000 autonomous floats that return oceanic climate data and has advanced the breadth, quality and distribution of oceanographic data.

As heat accumulates in the Earth’s oceans, they expand in volume, making this expansion one of the largest contributors to sea-level rise.

Although concentrations of greenhouse gases have risen steadily, the change in ocean-heat content varies from year to year, as the chart above shows. Year-to-year changes are influenced by events, such as volcanic eruptions and recurring patterns such as El Niño. In fact, in the chart one can detect short-term cooling from major volcanic eruptions of Mounts Agung (1963), El Chichón (1982) and Pinatubo (1991).

The ocean’s temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate crisis because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and influences weather patterns.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022, “Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Abraham, J. P., et al. (2013), “A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change,” Rev. Geophys.,51, 450–483, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rog.20022.

David Warsh: Spence Weart sums up the global-warming crisis that's upon us

Average surface air temperatures from 2011 to 2020 compared to a baseline average from 1951 to 1980 (Source: NASA)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Every April since I first read it, in 2004, I take down and re-read some portions of my copy of The Discovery of Global Warming (Harvard), by Spence Weart. (The author revised and expanded his book in 2008.) I never fail to be moved by the details of the story: not so much his identification of various major players among the scientists – Arrhenius, Milankovitch, Keeling, Bryson, Bolin – but by the account of the countless ways in which the hypothesis that greenhouse-gas emissions might lead to climate change was broached, investigated, turned back on itself (more than once), debated and, eventually, confirmed.

In the Sixties, Weart trained as an astrophysicist. After teaching for three years at Caltech, he re-tooled as a historian of science at the University of California at Berkeley. Retired since 2009, he was for 35 years director of the Center for the History of Physics of the American Institute of Physics, in College Park, Md.

This year, too, I looked at the hypertext site with which Weart supports his much shorter book, updating it annually in February, incorporating all matter of new material. It includes recent scientific findings, policy developments, material from other histories that are beginning to appear. The enormous amount of material is daunting. Several dozen new references were added this year, ranging from 1956 to 2021, bringing the total to more than 3,000 references in all. Then again, all that is also reassuring, exemplifying in one place the warp and woof of discussion taking pace among scientists, of all sorts, that produces the current consensus on all manner of questions, whatever it happens to be. Check out the essay on rapid climate change, for example.

Mainly I was struck by the entirely rewritten Conclusions-Personal Note, reflecting what he describes as “the widely shared understanding that we have reached the crisis years.”

Global warming is upon us. It is too late to avoid damage — the annual cost is already many billions of dollars and countless human lives, with worse to come. It is not too late to avoid catastrophe. But we have delayed so long that it will take a great effort, comparable to the effort of fighting a world war— only without the cost in lives and treasure. On the contrary, reducing greenhouse gas pollution will bring gains in prosperity and health. At present the world actually subsidizes fossil fuel and other emissions, costing taxpayers some half a trillion dollars a year in direct payments and perhaps five trillion in indirect expenses. Ending these payments would more than cover the cost of protecting our civilization.

Plenty else is going on in climate policy. President Biden is hosting a virtual Leaders Summit on Climate on Thursday, April 22 (Earth Day) and Friday, April 23. Nobel laureate William Nordhaus pushes next month The Spirit of Green: The Economics of Collisions and Contagions in a Crowded World (Princeton), reinforcing Weart’s conviction that it actually costs GDP not to impose a carbon tax on polluters. Public Broadcasting will roll out later this month a three-part series in which the BBC follows around climate activist Greta Thunberg in A Year to Change the World. And Stewart Brand, who in 1967 published the first Whole Earth Catalog, with its cover photo of Earth seen from space, is the subject of a new documentary, We Are as Gods, about to enter distribution. There is other turmoil as well. But if you are looking for a way to observe Earth Day, reading Spencer Weart’s summing-up is an economical solution.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

© 2021 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

—Graphic by Adam Peterson

At the PCFR: How can geo-engineering address global warming?

The Providence Committee on Foreign Relations’ (thepcfr.org; pcfremail@gmail.com) next dinner speaker, on Wednesday, Feb. 5, will be the internationally known science journalist, book author and coastal-erosion expert Cornelia Dean. With reference to sea-level rise caused by global warming, she’ll talk about geo-engineering -- the use of engineering techniques to alter Earth’s climate.

Some geo-engineering strategies are (relatively) uncontroversial, such as removing CO2 from the atmosphere. And some are controversial, such as seeding iron-poor ocean areas with iron to encourage plankton growth, the consequences of which are unknown and potentially unpleasant.

And consider the techniques known collectively as Solar Radiation Management. They include deliberate cloud-thinning, seeding the atmosphere with aerosols to make the planet more reflective, stationing mirrors in stationary orbit between Earth and the Sun, etc.

Cornelia Dean, a science writer and the former science editor of The New York Times, as well as a former deputy Washington Bureau chief of that paper, is well known for her knowledge of coastal-erosion issues as well as other scientific matters.

In her tenure running The Times’s science-news department, members of its staff won every major journalism prize as well as the Lasker Award for public service. She began her newspaper career at The Providence Journal. Her first book, Against the Tide: The Battle for America’s Beaches, was published in 1999 and was a New York Times Notable Book of the year. Her guide to researchers on communicating with the public, Am I Making Myself Clear?, was published in 2009. Her most recent (2017) book is Making Sense of Science: Separating Substance from Spin.

She has taught at Brown and Harvard and lectured in many other places, too

Please let us know if you're coming to the Feb 5. event by registering on our Web site, thepcfr.org, or emailing us at pcfremail@gmail.com. You may also call (401) 523-3957.

Joining the PCFR is simple and the dues very reasonable. Please check the organization’s Web site – thepcfr.org – email pcfremail@gmail.com and/or call (401) 523-3957 with any questions.

All dinners are held at the Hope Club, 6 Benevolent St., Providence. They begin with drinks at 6, dinner by about 6:40, the talk -- usually around 35-40 minutes – starts by dessert, followed by a Q&A. The evening, except for those who may want to repair to the Hope Club’s lovely bar for a nightcap, ends no later than 9 p.m.

xxx

And for the rest of the PCFR season, subject to the vagaries of weather, flu epidemics, cyberattacks and so on:

On March 18 comes Stephen Wellmeier, managing director of Poseidon Expeditions. He’ll talk about the future of adventure travel and especially about Antarctica, and its strange legal status.

xxx

News to come soon about an April 8 speaker, who will probably be an expert on the unrest in Hong Kong, and what it means for China and the world.

xxx

On Wednesday, April 29 comes Trita Parsi, founder and current president of the National Iranian American Council, author of Treacherous Alliance and A Single Roll of the Dice. He regularly writes articles and appears on TV to comment on foreign policy. He, of course, has a lot to say about U.S. Iranian relations.

xxx

On Wednesday, May 6, we’ll welcome Serenella Sferza, a political scientist and co-director of the program on Italy at MIT’s Center for International Studies, who will talk about the rise of right-wing populism and other developments in her native home of Italy.

She has taught at several U.S. and European universities, and published numerous articles on European politics. Serenella's an affiliate at the Harvard De Gunzburg Center for European Studies and holds the title of Cavaliere of the Ordine della Stella d'Italia conferred by decree of the President of the Republic for the preservation and promotion of national prestige abroad.

xxx

On Wednesday June 10, the speaker will be Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou, who directs the Initiative on Religion, Law, and Diplomacy, and is visiting associate professor of conflict resolution, at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. She titles her talk "God, Soft Power, and Geopolitics: Religion as a Tool for Conflict Prevention/Generation". She was originally scheduled for Dec. 5 but had to postpone because of illness.

Llewellyn King: Will Democrats break their Christmas present?

Historical sea level reconstruction and projections up to 2100 published in January 2017 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program for the Fourth National Climate Assessment.

The Democrats have no need to fret about what they’ll get for Christmas this year. Their worry shouldn’t be the gift, but rather how they choose to open it.

The gift is global warming.

Don’t call it climate change; that fuzzies the issue. Call it for what it is: global warming. It is heat that is melting the polar ice cap, stripping Greenland of its ice sheet, opening Arctic shipping lanes and sinking Venice, one of the jewels of civilization.

Global warming isn’t an existential threat but a real problem that is here, real and now. It is happening today, this hour, this minute, this second.

President Trump has taken his stand. He said of the rising seas and wild weather, which are science-supported evidence of global warming, “I don’t believe it.”

That is a political gift, shimmering and alluring. That is a target affixed to Trump. That is an image as evocative as Nero’s fiddling or Canute’s apocryphal ordering the waves from the incoming tide to stop. That is an opening wide enough for the Democrats to drive a truckload of election victories through.

Democratic strategists need to tell their candidates, “The climate, stupid!” All they must do is to hammer the Republicans and the administration relentlessly on the matter of global warming.

But this gift, looking so unassailable, may be undermined by the current stars on the left of the party. They have a sledgehammer approach and they may do damage to the gift before it is unwrapped.

Their passion is for the simplistic-but-seductive Green New Deal. It defines the problem as fossil fuels and wants to ban them. Then it prescribes the fixes. Bad move.

The cost and disruption of the fixes are ignored. That is why former Secretary of Energy Ernie Moniz -- a man who knows a lot about both politics and energy -- is pushing a concept he calls the Green Real Deal, which aims not to eliminate all fossil fuel use but to move to “net zero.” It means that many technologies will be used, including nuclear power and carbon capture and storage. It means that some fossil fuels will be used so long as their impact is mitigated by gains elsewhere.

These finer points of energy policy and environmental mitigation are too complicated for an election debate. They give too many opportunities for opposition ridicule. Too many handles for the Ridiculer in Chief and his acolytes to grab.

The Democrats need to repeat that the Republicans denied global warming even as the seas are rising. They need to sound the alarm that Boston, New York, Charleston and Miami may be headed for disaster very soon. They need to repeat it over and over, and then some more.

When running an election, a simple, repeatable message, without the details of how the goal will be achieved, wins the day. Clinton’s message served up by James Carville, “The economy, stupid!” won the day. Trump’s enticing “Make America Great Again” cry resonates.

The Democrats need only to dwell on rising sea levels and that the Republicans have repudiated the science. “The seas are rising and we’re going to do something about it,” is a reasonable Democratic message.\

Nixon showed us the effectiveness of framing the problem and hinting at a solution. “I have a plan,” he said about Vietnam. He didn’t mention it included bombing Cambodia.

The Democrats can win on a strong climate message. The seas are rising, wildfires ravage California year after year, Puerto Rico and other islands have been devastated by high-category hurricanes, and we may lose Venice.

A slam dunk in 2020? Don’t count on it. The Democrats likely will lard the message with social concerns, impossible marketplace tinkering and, in so doing, smash their winning gift as they open it. The Democrats are good at that, fatally so.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Tim Faulkner: The role of small New England farms in combatting global warming

— Photo Frank Carini, ecoRI News

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Farming and the climate crisis are no doubt interconnected even in relatively farm-scarce southern New England. But local farming operations, including fishing and aquaculture, are increasingly considered part of the climate-adaptation solution and may even help to mitigate global warming.

“How are we going to be more sustainable in our region and continue to feed ourselves?” asked Sue AnderBois, moderator of a panel on climate and food at the Oct. 4 Rhode Island Energy, Environment & Oceans Leaders Day hosted by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I.

As director for food strategy with the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation, AnderBois looks for business opportunities that advance food and farming policies in the state. There is definitely room to grow.

Rhode Island produces less than 5 percent of the food it consumes. This means that the Ocean State, and much of New England in fact, rely on food from places suffering from severe climate impacts such as drought-stricken California and the Amazon rainforest, a tropical region being destroyed to raise meat for fast-food restaurants.

Some of our local food sources are also moving away. Lobsters and other popular seafood staples are leaving Rhode Island waters because they are too warm. To counteract this change, the state is supporting businesses that market and process underutilized fish and plants and seafood moving into Rhode Island waters such as Jonah crab and black sea bass.

One of the panelists, Bonnie Hardy, canceled her appearance at the event to tend to work at her planned crab-processing facility in East Providence. A business processing local kelp is opening soon at the food incubator Hope & Main in Warren.

Consumers can contribute to the climate solution by buying local seafood, especially bivalves. A 2018 study found that eating local clams, mussels, oysters, and scallops is akin to a vegan diet when considering the carbon footprint.

On land, insects will be a growing climate problem for farming. Rising temperatures, a changing climate, and more frequent and intense rains will bring more pests. The state’s Division of Agriculture was overwhelmed this summer by efforts to address the spike in eastern equine encephalitis (EEE). The outbreak is a possible omen of future demands on state agencies, according to AnderBois.

Thanks to public pressure, food-service companies such as Sodexo and Aramak are offering more local food at schools and hospitals. Locally caught and processed dogfish is being used to make fish nuggets for public schools. Brown University, the Rhode Island School of Design, and Johnson & Wales University are all ramping up local food procurement for their kitchens and cafeterias, AnderBois said.

Nationally, however, such practices aren’t trending.

Government support for big agricultural operations at the expense of small farms hurts both local economies and the environment.

Jesse Rye, co-executive director of Farm Fresh Rhode Island, was appalled by the Trump administration’s recent decision to relocate federal research agencies such as the National Institute of Food and Agriculture from Washington, D.C., to the heart of “Big Ag” territory in Kansas City, Mo.

He said the actions by Trump favor large “commodity” farmers at the expense of small farms. The loss of research on nutrition and food insecurity is undermining the support structures for local food systems in southern New England, according to Rye.

”This way of disconnecting urban and rural communities is really going to erode the trust that we have in institutions, and I feel plays into the narrative that currently our government or this administration really only cares about the people that own food companies or own large-scale farms,” Rye said.

Any plan to address the climate crisis should take into account the most vulnerable, he said. It will require a “gigantic lift” to change consumer behavior and restructure the food system. He noted that a greater appreciation for scientific research and the true price of food is also necessary.

“We need to have a frank conversation as Americans about what cheap food is and how it’s possible and what are the costs that aren’t actually rolled into the costs we see at the supermarket.” Rye said, adding that society needs to recognize the environmental damage caused by continuing to do business as usual.

Rye urged the public to demand action from local, state, and national officials.

“If you have more time and energy for advocacy and outreach around issues for small farms now is the time to let your representatives hear that,” he said. “We need to let people know on a regional and national level that this is totally not acceptable.”

Brown University Prof. Dawn King, an expert on local food policy, agriculture, and the climate crisis, suggested that farms adhere to regulations for greenhouse-gas emissions as other businesses do. Farming, she noted, accounts for 10 percent of greenhouse gases in the United States and up to 25 percent of global emissions if deforestation is included.

Fertilizers, livestock, manure management, and tillage are the primary emission sources. King has researched manure as a source for compost and energy production. And farms, she said, if managed properly, can be one of the most effective carbon sinks.

“There is a lot we can do with carbon storage,” King said. “And even in Rhode Island that can be part of preserving the farmland that we desperately need to preserve here. Specifically, because we are not a farm state.”

Local farms can store carbon by growing grasses for small-scale beef production. Growing perennials and practicing forestry also capture and store carbon dioxide.

“Unfortunately, we are doing the exact opposite worldwide,” King said.

To get there, King called for a transformative initiative such as the Green New Deal combined with paying farmers to conserve land and practice sustainable soil management. Renewable-energy incentives should also be offered to help farmers earn additional revenue.

“We need to be sure we are protecting small farms,” she said.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News (ecori.org).

David Warsh: Economist's worst-case stance on global warming

California’s disastrous Camp Fire as seen from the Landsat 8 satellite on Nov. 8.

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

At first glance, it might have seemed anticlimactic, even crushing. The two young men had arrived together at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964, one from Swarthmore College, the other from Yale University. They completed their graduate studies three years later and, as assistant professors, taught together at Yale for the next five years. Then one returned to MIT and later moved to Harvard University, while the Yalie remained in New Haven. For the next dozen years, they worked on different problems, one on resource economics, the other on economies in which profit-sharing. as opposed to wages, would be the norm; until sustainability and global warming took over for both, far-seeing hedgehog and passionate fox.

Now the hedgehog had been recognized with a Nobel Prize that the fox had hoped to share, and the newly-announced laureate was speaking at a symposium to mark the retirement from teaching of the fox.

Don’t worry, you haven’t heard the last of Harvard’s Martin Weitzman. William Nordhaus, of Yale, shared the Nobel award this year for having framed the world’s first integrated model of the interplay among climate, growth, and technological change. But unless you believe the problem of global warming is going to go away, you are likely to meet Weitzman somewhere down the road. It just isn’t clear how or when.

At the moment, Weitzman is associated mainly with his so-called Dismal Theorem. The argument concerns “fat tailed uncertainty” or, as he describes it, the “unknown unknowns of what might go very wrong … coupled with essentially unlimited downside liability on possible planetary damages,” The structure of the reasoning was apparently well-known to high-end statisticians. Weitzman applied it first as a way to explain the so-called equity premium (why stocks earn so much more than bonds). Then, in 2009, introduced it to the global warming debate. Others have applied it since to fears about releasing genetically modified organisms.

Those unknown unknowns call for a more expensive insurance policy against their possibility than would otherwise be the case, Weitzman says, in the form of immediate countermeasures, You can hear him expound the case himself in an hour-long podcast with interviewer Russell Roberts. Better yet, read Weitzman and Gernot Wagner’s uncommonly well-written book Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet (Princeton, 2015).

(Copy editor: This seems a bit dashed off. EP: it is, too much so. I did a much better story about Thomas Schelling 25 years ago [“The Phone that Didn’t Ring”]. But I worked for a daily newspaper then, and I had less faith in the prize committee.)

On the other hand, if you have reservations about the worst-case way of framing policy choices, as does Nordhaus (along with many others), Weitzman has made other distinctive contributions, four in particular, which constitute tickets in some future lottery of fame.

The first has to do with a series of conceptual papers on “green accounting,” which involve ways of incorporating depreciation of natural resources into accounts of economic growth. The second involves contributions to the debate about the choice of discounting rates and intergenerational equity. The third concerns pioneering work on the costs and benefits of maintaining species diversity (the Noah’s Ark problem, the contribution Nordhaus gauged his most profound). The fourth has to do with his analysis of the means and risks of deploying various geoengineering measures to combat rapid warming – particularly injecting particles into the upper atmosphere, volcano-style, to shade the Earth from solar rays. And of course there is “Prices and Quantities,’’ from 1974, his most-cited paper, a durable contribution to comparative economics.

Global warming is a problem of staggering complexity. Economic activity caused the problem; economic analysis will be an important part of the response. If you believe the science, expect that this year’s laureates, Nordhaus and Paul Romer, of New York University, are only the first economists whose contributions will be recognized by the Swedes. Fat tails or not, time is God’s way of keeping everything from happening at once.

David Warsh, a columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, based in Somerville.

David Warsh: The Times and the WSJ in the hot-air debate

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A consensus seems to be emerging that climate change has begun exceeding its natural variability, and that accelerating global warming is something to be feared. What makes me think so? Accounts of widely shared experiences on the front pages of the newspapers that I read: forest fires; melting ice; famine, flood and drought; ecosystem collapse, and species loss. The Economist’s cover 10 days ago was, “Losing the War against Climate Change.”

What can we hope to do about it? It’s hard to tell, since, at least for the present, it seems only one problem among many: trade wars, international rivalries, urban-rural disparities, even arguments about the nature of truth. Yet many ways of narrowing differences exist, beginning with, as noted, the great but sometimes dangerous teacher of experience.

I’d like to suggest that we pay special attention to another mechanism. I think someone, not me, should carefully examine and compare the coverage that climate change receives from the three major American newspapers, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, with other nations and other languages soon to follow.

There is, obviously, a wide divergence in treatments of these issues. For example, the Aug. 5 Sunday Times magazine devoted an entire issue to a 30,000-word article accompanied by striking photographs of various disasters, titled “Thirty years ago, we could have saved the planet.” Meanwhile, the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, arguing that Trump administration deregulation policies were “improving consumer choice and reducing cost from health care to appliances,” celebrated the decision to freeze corporate average fuel-economy (CAFE) standards as “Trump’s Car Freedom Act.” The two issues are not tightly connected, the editorial argued, offering a crash course in the microeconomics of auto-emissions regulation in a dozen paragraphs.

The Times magazine was especially striking. Nathaniel Rich, the author, writes, “That we came so close, as a civilization, to breaking our suicide pact with fossil fuels can be credited to the efforts of a handful of people, a hyperkinetic lobbyist and a guileless atmospheric physicist, who at great personal cost, tried to warn humanity of what was coming.”

Of the story’s heroes, the lobbyist, Rafe Pomerance, seemingly had been born to his role: “He was a Morgenthau – the great-grandson of Henry Sr., Woodrow Wilson’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire; great-nephew of Henry Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary; second cousin to Robert, district attorney for Manhattan,” The physicist, James Hansen, had been the first to raise the alarm, as lead author of a Science paper, in 1982, then, forcefully, before a Senate hearing in the heatwave summer of 1988. Rich’s story has its villains, too: then-White House Chief of Staff John Sununu and Office of Management and then-Budget Director Richard Darman, who together blunted a drive to cap carbon emissions during the George H.W. Bush administration. And, of course, there is the author himself; the son of former Times columnist Frank Rich and HarperCollins executive editor Gail Winston. I don’t know about the three novels that Rich has published, but a previous article in the Times Magazine, about the history of a Dupont Co. product called PFOA, for perfluorooctanoic acid, was awfully good. This new article is divided into two chapters, with all the years since 1989 compressed into a short epilogue. My hunch is that they are drawn from a book in progress.

Rich’s article elicited a response from WSJ columnist Holman Jenkins, Jr., “Fuel Mileage Rules Are No Help to the Climate.” Incorporating the arguments of the paper’s editorial on the topic more or less by reference (he probably wrote the editorial), Jenkins disparaged Rich’s attachment to international climate treaties that “by their nature would have been collusion in empty gestures.” He scolded him for failing to note that “the U.S. has gone through umpteen budget and tax debates without a carbon tax — which is unpopular with the public, but so are all taxes – ever being part of the discussion.”

That seemed to be jumping the gun, given that Rich’s magazine article so clearly seemed part of a longer account. Perhaps later Rich will get around to the issue of quotas vs. prices as a way of limiting carbon dioxide emissions. Still, I was glad to see Jenkins bring up what seems to me to be the central issue of what can be done to curb global warming. He blamed “the green movement” for “hysterical exaggeration and vilifying critics” for the failure to obtain widespread support “the one policy that is nearly universally endorsed by economists, that could be a model of cost-effective self-help to other countries, that could be enacted in a revenue-neutral way that would actually have been pro-growth” (as opposed to a presumed drag on it).

I’m not so sure that the Greens, or even the Democrats, are mostly to blame. It’s true that the WSJ has periodically published op-ed pieces propounding carbon taxation – for instance, here. But if the paper’s editorial board has taken the initiative in arguing that global warming is a serious threat and that urgent measures are required to combat it, I haven’t noticed. Jenkins wrote, “A carbon tax remains a red cape to many conservatives, but in fact, it would represent a relatively innocuous adjustment to the tax code. It could solve political problems for conservatives (who want a tax code friendlier to work, savings, and investment) an as well as for liberals (who want action on climate change.)”

I was among those who were disappointed when The Times a year ago discontinued the position of its public editor. To that point it had been the leader among newspapers employing news professionals to plump for high standards of public discussion.

Other papers rely on columnists (like Jenkins) to augment debate. and preserve a semblance of even-handedness. Newspaper discourse is a little like an ongoing series of judicial proceedings. Acting as advocates – reporters, for readers; editorialists, for publishers – obey different rules to summon experts to support their pleadings. A seminal event in the saga of global climate study occurred 60 years ago when the U.S. established a carbon-dioxide observatory atop a volcano in Hawaii in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Who will establish an equally disinterested project to monitor major emissions of newspaper hot air — The Times’s magazine piece, the WSJ editorial page — on the topic of global warming?

David Warsh, a long-time economics and political columnist, is the proprietor of economicprincipals.com, based in Somerville, Mass.

Jill Richardson: Finding common language on global warming

Via OtherWords.org

If you don’t already agree with me on something, odds are I can’t convince you I’m right.

There’s plenty of science showing that the global climate crisis is already affecting us, that vaccines don’t cause autism, and that humans evolved from a common ancestor with apes. Yet many Americans don’t believe in man-made climate change, the safety of vaccines, or human evolution.

For the two-thirds of Americans who believe in human-caused climate change, the future is terrifying. If you fall in the other third, try to imagine for a moment how you’d feel if you did believe the planet was warming, ice caps were melting, seas were rising, and weather was getting more extreme.

I’ll be honest: I’m scared. Scared enough to seriously consider whether it would be wise or ethical to have children. And I’m frustrated and angry that our country isn’t doing enough to prevent the coming crisis.

I don’t want to take away anyone’s car or air conditioning. I don’t want to force anyone to go vegetarian, or limit the number of children Americans can have. There must be a way to decrease pollution and roll back the clock on climate change without compromising our lifestyles in an intolerable way.

But it won’t happen while we’re all bickering about whether or not the climate crisis is happening in the first place.

While the disagreement is most often on scientific terms, actual scientists don’t have any doubt at this point. The question isn’t whether the climate is changing, but how fast it’s changing and what will happen as a result.

But it’s only a small percentage of Americans who are truly scientifically literate. It takes a lot of education — not to mention time and access to academic journals — to actually comb through the literature and find the facts as researchers see them.

Most of us just base our conclusions on media reports of scientific studies or one of Al Gore’s movies.

Part of the problem is, perhaps, economic. It’s nice to talk about switching to clean energy, but that means jobs in fossil-fuel industries would go away. So far, this country hasn’t done much in the way of helping people transition to new careers.

No environmentalist wants coal miners or oil workers to be unemployed. We want them to have well-paying, satisfying jobs that allow them to live the lifestyle they enjoy — without hurting the planet.

The good news it that solar generation alone now employs more people than oil, gas, and coal combined. But in some places, the only alternatives to good coal jobs, for example, may be poorly paid service jobs with lower wages. Perhaps some people would have to move (or else demand their states invest more in renewables).

Ultimately, we need to find a common language to have a discussion, and we need to get serious about providing for anyone whose job will be lost by switching to clean energy.

Because the alternative is doing nothing — and then figuring out later how to help people whose homes are under water from sea-level rise or increasingly violent hurricanes.

Jill Richardson is a columnist for OtherWords,org.

At the PCFR: Global warming and international security

To members and friends of the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations (thepcfr.org; pcfremail@gmail.com).

Our next dinner comes on Nov. 15, with U. S. Naval War College Prof. James Holmes talking about the geopolitical and security issues presented by global warming,

Then on Dec. 14:

Jeffrey Frankel, James W. Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth at Harvard and former member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers. He will talk about international trade and when and if it’s good for national economies.