Llewellyn King: The dangerous cheapening of the impeachment process

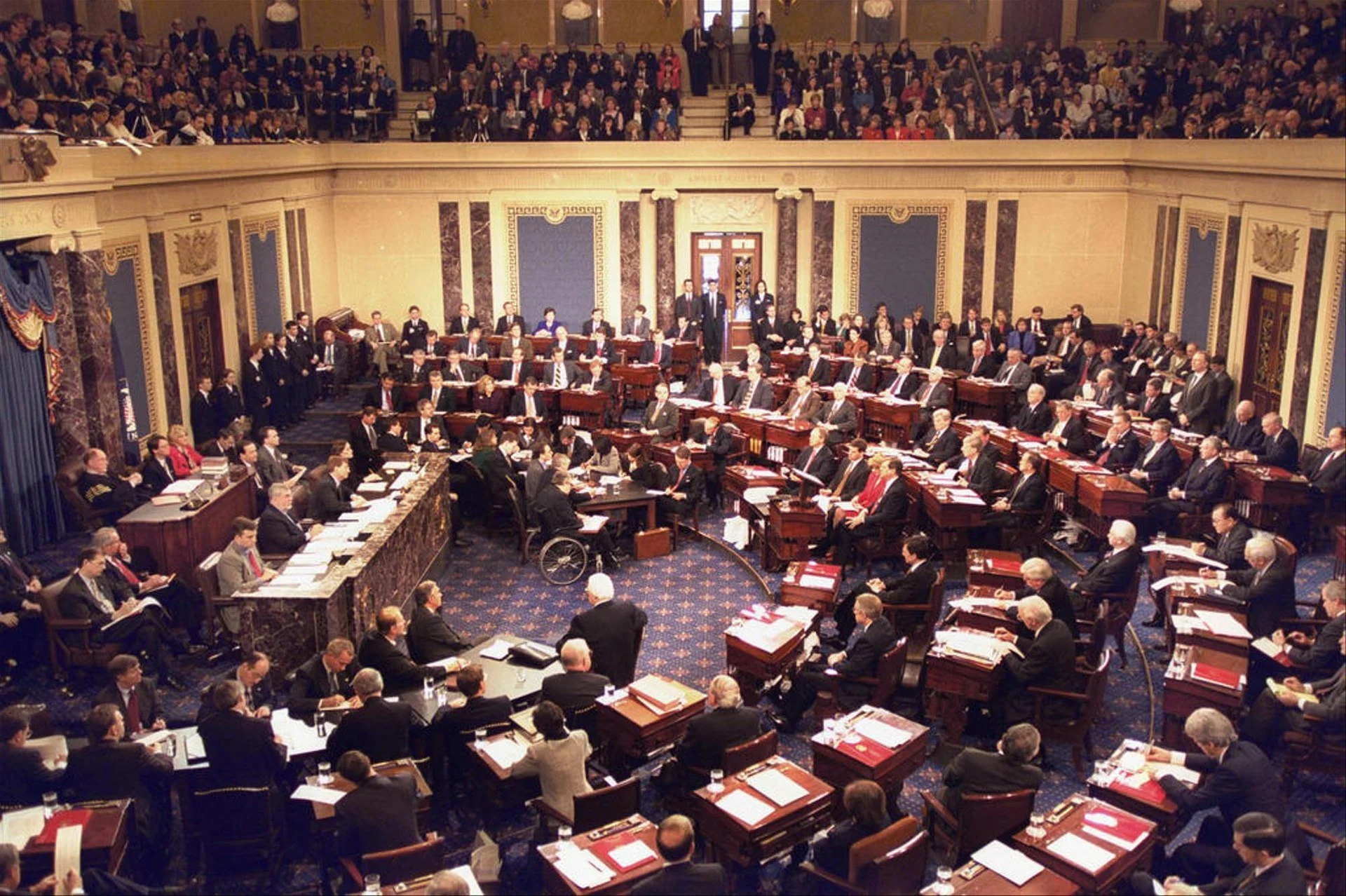

The impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, in 1999, with Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist presiding. The House managers are seated beside the quarter-circular tables on the left and the president's personal counsel on the right, much in the fashion of President Andrew Johnson's trial, in 1868.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Edmund Burke, the 18th-Century British statesman, argued during the celebrated impeachment of Warren Hastings, the governor of Bengal, that impeachment was essentially a political process, not a judicial one. Quite so.

The political dimension of impeachment is again on display in Washington, where the Republicans, driven by a faction of the party, are moving toward impeaching President Biden.

Historically, presidential impeachment has been reserved for actions that meet the undefined standard of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” It has been used with great restraint; until the impeachment of Bill Clinton, only Andrew Johnson had been impeached. The bar was lowered for the Clinton action then, and the attempt to impeach Biden is a further lowering — pointing up that it is, as Burke argued, a political process.

Impeachment is becoming a common political tactic not, as envisaged by the Founders, the ultimate censure, leading to a trial in the Senate and removal from office.

The two indictments of Donald Trump would seem to have met, to my mind, the constitutional standard and, had the Senate been in other hands, might have led to a trial and removal. It is argued that those indictments didn’t meet the standard and were no more than censure by another name, carried out along party lines.

The gravity of impeachment has been preserved since the beginning of the republic, but it is in danger.

Some aspects of the structure of the state should be out of reach to the political process most of the time. The U.S. Constitution guarantees that it can’t be easily amended or today it wouldn’t be recognizable, as every fashionable fixation would have been added. The mistake of Prohibition written again and again.

At the time that the Northern Ireland peace accords were being written, I was involved with a lively summer school in Ireland — which might be thought of as a think tank that meets once a year.

This organization, the International Humbert Summer School, studied Ireland’s relationship to the world, but became involved in the peace process. There were speakers from both the Unionists (pro-British) and Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA.

At one session, my role was to respond to the late Martin McGuinness, widely known as a top leader of the IRA, believed by the British to be a terrorist with blood on his hands.

Because I have a British accent, the organizers, John Cooney, the Irish historian and journalist, and Tony McGarry, a prominent local headmaster in Ballina, County Mayo, where we gathered, were nervous about what I might say to a man who was regarded with fear and awe as a killer.

Our event turned into a debate. McGuinness was sharp, had a good sense of humor and was open to ideas. Because the IRA had been engaged in armed struggle for so long, it hadn’t thought about constitutional arrangements in peace.

Thinking of the U.S. Constitution, I suggested to McGuinness that if a new constitution for Northern Ireland were to be written, it should sweep nothing under the carpet by ignoring it (as was the American case with slavery) and that when finished, it should be placed on “a high shelf” from which it couldn’t be easily taken down.

McGuinness agreed heartily, and this led to a discussion of constitutions and systems of government, and how the drafting could be perfected.

But my idea of a high shelf was what stuck with him.

So it is deeply disheartening to see impeachment treated as just another political tactic to be launched against any American president simply because the opposition party doesn’t like the president’s policies. But that is what is happening.

Incidentally, the impeachment of Warren Hastings, which dragged on for years and was enormously expensive, ended in acquittal before the House of Lords, proving Burke’s point that impeachment was a political process.

In the United States, for most of our history we have avoided keeping it out of the political maelstrom. It is a sad thing to see used now as a purely political tactic.

We have what is essentially a permanent campaign for the presidency. No sooner is one election certified then rumblings about the next one, with all the attendant speculation, begin.

Will presidential impeachment become part of the political process? And what if a Senate has the two-thirds majority to convict on political grounds? There is danger here.

At the end of our exchange, I wished the IRA leader “the best of British luck.” He laughed. No attempt to kneecap me followed.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Perhaps better to censure rather than impeach corrupt would-be dictator Trump

Warren Hastings (1732 –1818), impeached and acquitted

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Impeachment is a procedure of last resort. It is for when those governed are unable to abide the excesses of one or more persons doing the governing. It owes its genesis to England and was a remedy for the Parliament to remove, or have removed, agents of the Crown (the King) whose conduct was egregious and contrary to the public good.

It goes back to the 14th Century. The language is the language of the day, peculiarly vague in today’s proceedings. “High crimes and misdemeanors” was one of those phrases which everyone in the context of the day knew what it meant. “Conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman” is another such phrase loaded with meaning but deliberate in its obscurity.

It was not until 1788 that Edmund Burke, the great Anglo-Irish orator, moralist and member of Parliament, really put flesh on the skeleton of impeachment. During the impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal and employee of the marauding British East India Company -- which had been acting as a government in India before it was annexed by Britain. He was the agent of what was little more than a criminal enterprise.

Hastings claimed that he was given arbitrary power by the East India Company to act in any way he chose. It was this arbitrary power, this concept that he was above the law and above all norms of decency, that inflamed Burke. “We have no arbitrary power to give, because arbitrary power is a thing which neither any man can hold, nor any man can give. No man can lawfully govern himself according to his own will – much less can one person be governed by the will of another,” he said.

Burke stated that there was no entitlement to arbitrary power in any human institution, and it could not be conferred on a governor by anyone because there was no entitlement under heaven for arbitrary power.

It can be argued in today’s crisis it is the exercise of arbitrary power by President Trump that lies behind the U.S. House’s move to impeach. Arbitrary power in diverting funds not approved for that purpose to building a wall on the southern border. Arbitrary power in restricting Congress’s entitlement to investigate the executive branch. On and on the use of what many would call arbitrary power, from abrogating treaties, abandoning allies, trashing traditions, and reversing previous settled issues, like the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

All this, Trump asserts, is constitutional under Article 11. In essence, he has said, “Arbitrary power is mine.”

That is what lies behind the urge to impeach Trump. He is claiming to be, in conduct and statement, above the Constitution and the law. Ergo, he should be impeached.

But no. Impeachment, as Burke and his allies found, is a trap unless followed by conviction. In Hastings’ case, impeachment was up to the House of Lords and, despite the pleading of Burke and others, it declined to impeach after the procedure had dragged on for seven years.

Given the pusillanimous nature of the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate, its seeming preparedness to overlook damage to the constitutional order of governance and all the cascading damage to come down through the years, Trump’s acquittal is to be feared.

Trump in a second term, with the sense that he had been vindicated, would have no regard for law. He would feel emboldened to exercise arbitrary power in the most egregious way, rewarding his business interests and punishing his enemies, real and imagined.

As others have suggested, a better path for Democrats to pursue in the present constitutional crisis might have been to censure Trump, while looking to the courts to restrict him where possible. A less dramatic indictment, but also less of a future danger.

Republicans have developed an interesting defense of their own. Call it “the eye-rolling, tut-tutting.” They do this whenever Trump is raised in conversation, but they will not curb him in the Senate or speak out in public. Political cowardice.

These lily-livered legislators might find courage if they read on in Burke’s pleading in the matter of Hastings: “Those who give and those who receive arbitrary power are alike criminal; and there is no man but is bound to resist it in the best of his power, wherever it shall show its face to the world.”

There is much more from Burke. It is meaty, relevant stuff.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington.