Christopher Niezrecki: What has hurt the offshore wind industry, and what to do about it

The five-turbine wind farm off Block Island

LOWELL, Mass.

America’s first large-scale offshore wind farms began sending power to the Northeast in early 2024, but a wave of wind farm project cancellations and rising costs have left many people with doubts about the industry’s future in the U.S.

Several big hitters, including Ørsted, Equinor, BP and Avangrid, have canceled contracts or sought to renegotiate them in recent months. Pulling out meant the companies faced cancellation penalties ranging from US$16 million to several hundred million dollars per project. It also resulted in Siemens Energy, the world’s largest maker of offshore wind turbines, anticipating financial losses in 2024 of around $2.2 billion.

Altogether, projects that had been canceled by the end of 2023 were expected to total more than 12 gigawatts of power, representing more than half of the capacity in the project pipeline.

So, what happened, and can the U.S. offshore wind industry recover?

Estimates of the mean annual wind speeds in meters per second extending 200 kilometers from shore at a height of 330 feet (100 meters). ESMAP/The World Bank via Wikimedia, CC BY

I lead UMass Lowell’s Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research WindSTAR and Center for Energy Innovation and follow the industry closely. The offshore wind industry’s troubles are complicated, but it’s far from dead in the U.S., and some policy changes may help it find firmer footing.

Long approval process’s cascade of challenges

Getting offshore wind projects permitted and approved in the U.S. takes years and is fraught with uncertainty for developers, more so than in Europe or Asia.

Before a company bids on a U.S. project, the developer must plan the procurement of the entire wind farm, including making reservations to purchase components such as turbines and cables, construction equipment and ships. The bid must also be cost-competitive, so companies have a tendency to bid low and not anticipate unexpected costs, which adds to financial uncertainty and risk.

The winning U.S. bidder then purchases an expensive ocean lease, costing in the hundreds of millions of dollars. But it has no right to build a wind project yet.

Continental shelf areas leased for wind power development along the Atlantic coast. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024

Before starting to build, the developer must conduct site assessments to determine what kind of foundations are possible and identify the scale of the project. The developer must consummate an agreement to sell the power it produces, identify a point of interconnection to the power grid, and then prepare a construction and operation plan, which is subject to further environmental review. All of that takes about five years, and it’s only the beginning.

For a project to move forward, developers may need to secure dozens of permits from local, tribal, state, regional and federal agencies. The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which has jurisdiction over leasing and management of the seabed, must consult with agencies that have regulatory responsibilities over different aspects in the ocean, such as the armed forces, Environmental Protection Agency and National Marine Fisheries Service, as well as groups including commercial and recreational fishing, Indigenous groups, shipping, harbor managers and property owners.

For Vineyard Wind I – which began sending power from five of its 62 planned wind turbines off Martha’s Vineyard in early 2024 – the time from BOEM’s lease auction to getting its first electricity to the grid was about nine years.

Costs can balloon during the regulatory delays

Until recently, these contracts didn’t include any mechanisms to adjust for rising supply costs during the long approval time, adding to the risk for developers.

From the time today’s projects were bid to the time they were approved for construction, the world dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, global supply chain problems, increased financing costs and the war in Ukraine. Steep increases in commodity prices, including for steel and copper, as well as in construction and operating costs, made many contracts signed years earlier no longer financially viable.

New and re-bid contracts are now allowing for price adjustments after the environmental approvals have been given, which is making projects more attractive to developers in the U.S. Many of the companies that canceled projects are now rebidding.

The regulatory process is becoming more streamlined, but it still takes about six years, while other countries are building projects at a faster pace and larger scale.

Shipping rules, power connections

Another significant hurdle for offshore wind development in the U.S. involves a century-old law known as the Jones Act.

The Jones Act requires vessels carrying cargo between U.S. points to be U.S.-built, U.S.-operated and U.S.-owned. It was written to boost the shipping industry after World War I. However, there are only three offshore wind turbine installation vessels in the world that are large enough for the turbines proposed for U.S. projects, and none are compliant with the Jones Act.

That means wind turbine components must be transported by smaller barges from U.S. ports and then installed by a foreign installation vessel waiting offshore, which raises the cost and likelihood of delays.

A generator and blades head for the South Fork Wind farm from New London, Conn., on Dec. 4, 2023. AP Photo/Seth Wenig

Dominion Energy is building a new ship, the Charybdis, that will comply with the Jones Act. But a typical offshore wind farm needs over 25 different types of vessels – for crew transfers, surveying, environmental monitoring, cable-laying, heavy lifting and many other roles.

The nation also lacks a well-trained workforce for manufacturing, construction and operation of offshore wind farms.

For power to flow from offshore wind farms, the electricity grid also requires significant upgrades. The Department of Energy is working on regional transmission plans, but permitting will undoubtedly be slow.

Lawsuits, disinformation add to the challenges

Numerous lawsuits from advocacy groups that oppose offshore wind projects have further slowed development.

Wealthy homeowners have tried to stop wind farms that might appear in their ocean view. Astroturfing groups that claim to be advocates of the environment, but are actually supported by fossil fuel industry interests, have launched disinformation campaigns.

In 2023, many Republican politicians and conservative groups immediately cast blame for whale deaths off the coast of New York and New Jersey on the offshore wind developers, but the evidence points instead to increased ship traffic collisions and entanglements with fishing gear.

Such disinformation can reduce public support and slow projects’ progress.

Efforts to keep the offshore wind industry going

The Biden administration set a goal to install 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030, but recent estimates indicate that the actual number will be closer to half that.

Passengers on a boat view America’s first offshore wind farm, owned by the Danish company Ørsted. Its five turbines generate power off Block Island, R.I. AP Photo/David Goldman

Despite the challenges, developers have reason to move ahead.

The Inflation Reduction Act provides incentives, including federal tax credits for the development of clean energy projects and for developers that build port facilities in locations that previously relied on fossil fuel industries. Most coastal state governments are also facilitating projects by allowing for a price readjustment after environmental approvals have been given. They view offshore wind as an opportunity for economic growth.

These financial benefits can make building an offshore wind industry more attractive to companies that need market stability and a pipeline of projects to help lower costs – projects that can create jobs and boost economic growth and a cleaner environment.

Christopher Niezrecki is director of the Center for Energy Innovation at the Center for Energy Innovation at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Mr. Niezrecki is director of UMass Lowell’s Industry-University Cooperative Research Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research (WindSTAR), which receives funding from the National Science Foundation and several energy-related companies.

Mary Lhowe: The ‘lunchbox’ from offshore wind turbines

Text from ecoRI News article by Mary Lhowe

“Opponents of offshore wind offer different reasons for their position: fear of impacts on the marine ecology; fear of loss of income for fishers; fear of loss of tourism dollars and private property values due to the sight of the turbines on the horizon.

“The cloudy threat of wind projects off the New England coast comes with a golden — not silver — lining. That gold would arrive in the form of millions of dollars contractually promised to communities by developers in the form of mitigations, sometimes through a mechanism called host community or good neighbor agreements.

Even the towns and historic property owners who dread wind farms but yearn for funds to do worthy projects could be excused for reacting to mitigation deals in similar fashion to the character Gaz in the movie The Full Monty. Watching men audition for a new amateur dance troupe, Gaz observes the impressive talents of one particular auditioner, and mutters, “Gentlemen, the lunchbox has landed.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: The brazen and well-financed disinformation campaign of the anti-wind-farm crowd

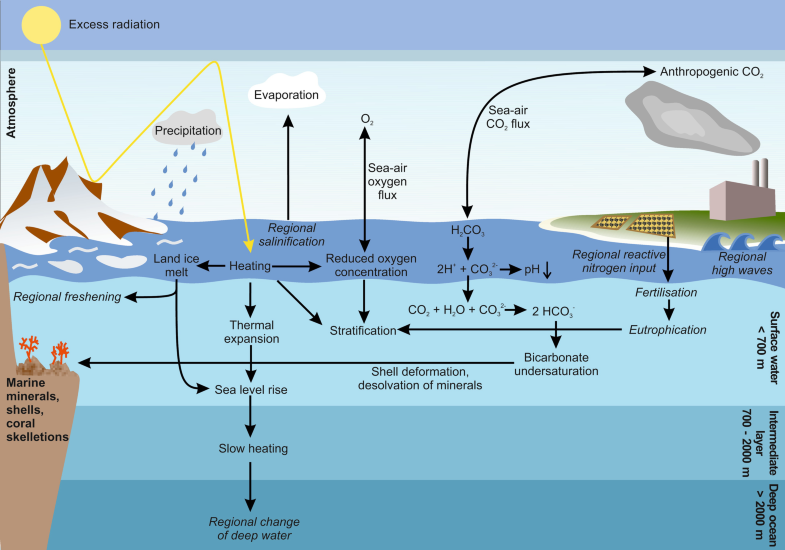

Overview of climatic changes caused by burning fossil fuel and their effects on the ocean. Regional effects are displayed in italics.

Oil spill covering kelp.

The anti-wind mob chums the waters with red herring. The conspiracy theorists continue to hide behind critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to spin tales about offshore wind. Their faux concern is nauseating.

When it comes to the real threats to the 350 or so North Atlantic right whales left on the planet — entanglements with fishing gear and strikes with ships — the mob’s ranting and raving goes largely silent, and my stomach turns.

These self-proclaimed pro-whale warriors only care about the lives of these majestic marine mammals when they fit into their manufactured hysteria about offshore wind.

Among those spreading the mob’s propaganda are southern New England firebrand Lisa Quattrocki Knight, president of Green Oceans, and Constance Gee, a Westport, Mass., resident and Green Oceans member; Lisa Linowes, executive director of the Industrial Wind Action Group Corp, also known as The WindAction Group; Protect Our Coast New Jersey; and blogger Frank Haggerty, a blowhole of offshore wind misinformation.

Their bluster is either funded by the fossil-fuel industry and/or they are wealthy coastal property owners more concerned that their ocean views will be ruined by a different type of energy infrastructure. Either way, the lives of whales, dolphins, birds, and humans living near polluting fossil-fuel operations don’t matter.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: The staggering hypocrisy of the anti-offshore wind farm crowd

From Frank Carini’s column “Whale of a Tale: Local Anti-Wind Crowd Spins Yarns,’’ in ecoRI News (ecori.org)

”No energy source is benign. From installation to operation, they all come with consequences — environmental, societal, and cultural. Some more than others. Legitimate concerns (e.g., not infringing upon whale migration corridors) must be studied, discussed, mitigated, and/or avoided. Renewable energy shouldn’t be called clean, but it is a whole lot cleaner than fossil fuels….

“The concerns of southern New England’s anti-offshore wind crowd, however, never spill over to the polluting gas and oil platforms that mar many of the waters off the U.S. coast, especially in the Gulf of Mexico. Probably because there are no such rigs in Rhode Island Sound.

“They don’t mention sonar {which can disturb marine mammals} is used to detect leaks from offshore fossil fuel infrastructure. They fail to note ocean military training drills use sonar, and live munitions. They disregard the fact the primary causes of mortality and serious injury for many whales, most notably the North Atlantic right whale, are from entanglements with fishing gear and vessel strikes.

“Even though data show that North Atlantic right whale mortalities from fishing entanglements continue to occur at levels five times higher than the species can withstand, the anti-wind crowd isn’t calling for fishing gear to be pulled from local waters or the use of ropeless fishing technology made mandatory. They aren’t demanding vessels be equipped with technology that monitors the presence of whales in shipping lanes.

“They ignore the fact the development of offshore wind is the most scrutinized form of renewable energy. After reading this column, they will allege I and/or ecoRI News are in the pocket of Big Wind. We’re not. (A few wind energy companies have advertised with us, but they didn’t spend nearly enough to bankroll a golden parachute, or even a reporter’s salary for a month.)

“The anti-wind crowd doesn’t offer any real solutions to drastically reduce the amount of heat-trapping, polluting, and health-harming greenhouse gases that humans are relentlessly spewing into the atmosphere.’’

To read the full column, please hit this link.

Grace Kelly: Floating turbines may be part of New England offshore-wind network

Floating turbines come in various styles.

— Joshua Bauer/U.S. Department of Energy

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The winds and airs currents swirling around the oceans of this blue marble have the potential to power our cities and towns. And locally in coastal New England, the race to harness the power of coastal wind has been accelerating.

Last year then-Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order that called for an ambitious, yet somewhat vague, “100 percent renewable energy future for Rhode Island by 2030” — a good portion of which would be from offshore wind.

“There is no offshore wind industry in America except right here in Rhode Island,” Raimondo said at the time. She was referring to the groundbreaking five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm, a 30-megawatt project that was the first commercial offshore wind facility in the United States.

Today, there is a slightly different picture forming, and other New England states, notably Massachusetts and Maine, are looking into becoming a part of a regional offshore wind network.

During a March 18 online presentation, Environment America discussed a recently released report detailing the overall potential that offshore wind has, specifically in New England. The discussion also included presentations from experts in the field of offshore wind.

“We found that the U.S. has a technical potential to produce more than 7,200 terawatt-hours of electricity in offshore wind,” said Hannah Read of Environment America, a federation of state-based environmental advocacy organizations. “What we did was we compared that to both our electricity used in 2019 and the potential electricity used in 2050, assuming that we transition society to run mostly on electric rather than fossil fuels, and what we found is that offshore wind could power our 2019 electricity almost two times over, and in 2050 could power 9 percent of our electricity needs.”

On a more granular level, Read said Massachusetts has the highest potential for offshore-wind-generation capacity, and Maine has the highest ratio of potential-generation capacity relative to the amount of electricity that it uses.

Massachusetts is entering the final stages of the federal permitting process for the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project, which is slated to start construction next year and go online in 2023.

“We have some real frontrunners here in New England and we have a huge opportunity to take advantage of this resource,” Read said. “When you look at the New England as a region, it could generate more than five times its projected 2050 electricity demand.”

While Rhode Island and Massachusetts are looking to more traditional fixed-bottom turbines, in coastal Maine, where coastal waters are deeper, researchers at the University of Maine are testing prototypes for floating wind turbines.

“The state of Maine has deep waters off its coasts. If you go three nautical miles off the coast … you’re in about 300 feet of water,” said Habib Dagher, founding executive director of the Advanced Structures & Composites Center at the University of Maine. “Therefore, you can’t really use fixed-bottom turbines.”

To mitigate this, Dagher and his team have been building and testing floating turbines for the past 13 years, using technology from an unlikely source.

“There are three different categories of floating turbines and ironically enough we have the oil and gas industry to thank for developing floating structures,” Dagher said. “We borrowed these designs … and adapted them to floating turbines.”

Many of these floating turbines rely on mooring lines and drag anchors to keep them from floating away, and they come in various styles.

Dagher noted that while other states are able to pile-drive turbines, they should consider floating turbines as another way to fit more wind power into select offshore areas that could become crammed full.

“We’re going to run out of space to put fixed-bottom turbines. We have to start looking at floating … on the Massachusetts coast and beyond, in the rest of the Northeast,” he said.

Shilo Felton, a field manager for the Audubon Society’s Clean Energy Initiative, addressed another issue facing offshore wind: bird migration patterns. Focusing on the northern gannet, a large seabird, she explained that while climate change itself is negatively affecting bird populations, it is important to take care that offshore wind doesn’t make the situation worse.

She noted that Northern Gannets experience both direct and indirect risks from offshore wind. “Direct risks are things like collision, indirect risks are things like habitat loss,” Felton said.

But Felton also acknowledged that since we don’t really have lots of large-scale wind projects in the United States currently, it’s hard to really say how much those risks will impact bird populations.

“We don’t have any utility-scale projects yet, so we don’t really know how the build out in the United States is going to impact species,” she said. “So that requires us to take this adaptive management approach where we monitor impacts as we build out so that we can understand what those impacts are.”

Overall, the potential that offshore wind holds as a viable mitigation tactic in the fight to curb and eventually eradicate greenhouse-gas emissions is great. But, as speakers noted, implementation has to be done thoughtfully and thoroughly.

Referring specifically to Maine, Dagher said, “The state is moving on to do a smaller project of 10 to 12 turbines, and that would help us crawl before we walk, walk before we run. Start with one, then put in 10 to 12 and learn the ecological impacts, learn how to work with fisheries, learn how to better site these things before we go out and do bigger projects in the future.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News journalist.

Annie Sherman: Offshore wind turbines can benefit fishing

Wind turbines of Denmark

Since the Block Island Wind Farm, four years ago, pioneered U.S. offshore wind development, the United States has positioned itself to become a world producer of electricity in this renewable-energy sector. Turning the wind’s kinetic energy into electrical power is gaining popularity, so much so that 2,000 offshore wind turbines could be erected off the East Coast in the next 10 years.

But with growth comes questions and resistance, so scientists and environmental advocates across the country and in Rhode Island are seeking opportunities to expand offshore renewable energy while reducing environmental risks.

With world-class fisheries and wildlife in Ocean State waters, the potential for victory seems on par with ruin. So it’s vital to understand how the trifecta interacts symbiotically: offshore wind facilities, current recreational and commercial uses, and the existing ecosystem.

“As we experience this growth, we see that the state and local decision-makers, resource users, and other end users are struggling to keep up with the decisions they’re having to make and also understand the potential impact it may have on existing activities and natural wildlife,” said Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. coastal programs at the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center. “While some places in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Europe have been working in this game for many years, there are others who are just beginning to ask questions and get their bearings on this growth. Given this growth is likely, [we need to] better understand how can we minimize the effects on existing future uses and wildlife.”

The development of offshore renewable energy has already exploded in Europe. WindEurope estimates that it now has offshore wind capacity of 22.1 gigawatts from 5,047 grid-connected offshore wind turbines across 12 countries, with 502 turbines installed last year alone. Scientists and researchers there already are coming to terms with the risk and impacts, both positive and negative, of offshore wind turbines.

Sharing their knowledge about the U.S. market in a June webinar, moderated by McCann, with Rhode Island Sea Grant and URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, two experts said the impacts on the environment are steep. They advocated for proper management and reduced activity to maintain a healthy marine environment.

Jan Vanaverbeke, a senior scientist at the Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences, and Emma Sheehan, a senior research fellow at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, presented more than a decade of research from investigating the change in biological diversity and ecological interactions resulting from offshore renewable-energy structures.

Their research began at the smallest scale, with tiny marine animals and microorganisms inhabiting a turbine when it’s first installed, Vanaverbeke said. Huge numbers of this diverse marine life make a home at the base of these 600-foot-high, 200-ton turbines affixed to the seabed. This area also attracts other animals such as fish and crustaceans. They noted how offshore aquaculture and offshore energy infrastructure can support each other and improve the diversity of marine ecosystems.

“Abiotic effects, like currents, vibration, noise, and electromagnetic fields, will have an affect on the biology,” Vanaverbeke said. “In this case, it would deliver food for society, because certain fish species, like cod and pouting, were attracted to turbines. … What we see in the scour protection layer [a layer of material to protect erosion around the turbine] shows increased diversity, giving additional complexity and shelter for species.”

He also saw evidence of this conflicted cause-and-effect relationship when additional marine animals were drawn to the turbines, as they affected sediment and water quality. Taking organic matter and food from the water, they also excrete matter, which sinks to the seabed and negatively alters the sedimentary environment.

“Offshore wind farms actually do change the habitat and the environment,” Vanaverbeke said. “Research will inform you of consequences of those changes, and how to understand what this change will mean for the larger marine ecosystem. We actually want to apply this knowledge for marine spatial planning. We can see where to put the wind farm, where is the best place from an ecosystem perspective. We have to know about carrying capacity for aquaculture activities. We can also use this knowledge for a better wind farm design, in such a way that they would contribute to nature restoration and conservation, or we can play around with the complexity of the scour protection layer and use it as a nature restoration tool.”

Sheehan expanded on their research with her analysis of ecological interactions between offshore installations and the potential benefits of ambitious management. Highlighting Marine Protected Areas (MPA), a fresh or saltwater zone that is restricted to human activity, Sheehan focused on ecosystem-based fisheries management and offshore installations that have the potential to be super MPAs, by excluding destructive fishing practices and adding habitat.

She noted the term “ocean sprawl,” similar to urban sprawl, which is becoming more widely known as pressure increases for offshore energy installations.

Sheehan said it’s important to consider the benthos and their associated fish communities, because they are the foundation for the entire marine ecosystem.

Reducing or eliminating bottom fishing, which she said is destructive of rocky reefs and sediment habitats, is one way to protect these important marine areas. In one MPA she has been studying for 13 years, scallop dredging was prohibited, which ultimately allowed reef-associated species to return.

Since the siting of most offshore wind facilities is on these habitats, Sheehan advocated for installations to be progressively managed like de facto MPAs, to support essential fish habitats and protect the seabed.

“There is lots of potential for environmental benefit of co-locating offshore aquaculture with offshore renewables from an environmental point of view, but also from an economic point of view, because sharing space is going to be the only way we can move forward for this industry,” Sheehan said. “If bottom-towed fishing is excluded from the whole site, offshore developments can have positive effects on the ecosystem, increase ecosystem services, support other fisheries, and help us move toward a carbon-neutral society.”

Annie Sherman is a freelance journalist based in Newport, R.I., covering the environment, food, local business, and travel in the Ocean State and New England. She is the former editor of Newport Life magazine, and author of Legendary Locals of Newport.

Tim Faulkner: Is fossil-fuel-loving Trump regime trying to sabotage offshore wind?

Vineyard Wind is coming to terms with the fact that its wind project is behind schedule, as accusations of political meddling escalate.

On Feb. 7, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) released an updated permitting guideline that moved the facility’s likely completion date beyond Jan. 15, 2022 — the day the $2.8 billion project is under contract to begin delivering 400 megawatts of electricity capacity to Massachusetts.

Vineyard Wind is now renegotiating its power-purchase agreement with the three utilities that are buying the electricity. The company is also in discussions with the Treasury Department about preserving an expiring tax credit.

The delay is being caused by a holdup with BOEM’s environmental impact statement (EIS). A draft of the report was initially expected last year, but after the National Marine Fisheries Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declined to endorse the report, it was pushed off until late 2019 or early 2020. Back then several members of Congress from Massachusetts claimed the delay was politically motivated.

BOEM now is predicting that the draft EIS won’t be ready until June 12, with a final decision by Dec. 18. The setback is significant because the draft EIS is being counted on to shape the mapping of other offshore wind facilities slated for the seven federal wind-energy lease areas off the coasts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

The Coast Guard recently released its Massachusetts and Rhode Island Port Access Route Study (MARIPARS). The report favors the grid design proposed by wind developers and discounted concerns about radar interference.

This navigational safety report also recommends that if the turbine layout in the entire Massachusetts and Rhode Island wind area is developed using “a standard and uniform grid pattern” then special vessel routing lanes wouldn’t be required.

The Coast Guard’s findings improve the prospect for development of all seven wind-energy lease areas. But the MARIPARS report and the draft EIS both require public comment periods and hearings.

Lars Pedersen, CEO of Vineyard Wind, said of the setback, “We look forward to the clarity that will come with a final EIS so that Vineyard Wind can deliver this project to Massachusetts and kick off the new U.S. offshore energy industry.”

This latest delay has again been criticized by members of the Massachusetts congressional delegation as a ploy by President Trump to demonstrate his aversion to wind energy and his favoritism for fossil-fuel companies.

On Feb. 5, two days before BOEM released the new timeline, Massachusetts’ two U.S. senators and seven members of Congress sent a letter to the U.S. Government Accountability Office expressing their outrage over Trump’s hypocrisy.

“Despite seeking expedited environmental reviews for numerous fossil fuel infrastructure projects, Trump administration officials in the Department of the Interior have ordered a sweeping environmental review of the burgeoning offshore wind industry, a move that threatens to stall or even derail this growing industry, and raises a host of questions for future developments,” according to the letter.

In a recent interview with the Vineyard Gazette, Rep. Bill Keating, D-Mass., whose district includes Martha’s Vineyard, said he believes BOEM planned to release the draft EIS much sooner, but stalled the report after political pressure from superiors in the Department of Interior or the Trump administration until after the presidential election in November.

“It’s clear to me that these are political decisions and not guided by wanting to mitigate environmental impacts,” Keating said.

When asked about the political interference, BOEM replied that the delays are caused by public comments that call for a more thorough review of a large and disruptive change to nearshore waters. Those comments cited the upsurge in new wind projects, an increase in the size of wind turbines used by Vineyard Wind, and potential conflicts with commercial fishing and navigation.

Meanwhile, investments in wind project port facilities continue along southern New England. Gov. Gina Raimondo has earmarked $20 million in her proposed budget for improvements to the Port of Davisville at the Quonset Business Park in North Kingstown, R.I. The work includes dredging, repair of an existing pier, and construction of a new pier.

Mayflower Wind, the next project after Vineyard Wind to win an energy contract from Massachusetts, recently announced its intention to make the New Bedford Marine Terminal its primary construction hub for its 804-megawatt project.

Tim Faulkner is an ecoRI News journalist.

Tim Faulkner: Future of offshore wind hangs on agency's report

Progression of expected wind turbine evolution to deeper water

From ecoRI News

The forthcoming report from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) on the cumulative environmental impacts of the Vineyard Wind project will determine the future of offshore wind development.

BOEM’s decision isn’t just the remaining hurdle for the 800-megawatt project, but also the gateway for 6 gigawatts of offshore wind facilities planned between the Gulf of Maine and Virginia. Another 19 gigawatts of Rhode Island offshore wind-energy goals are expected to bring about more projects and tens of billions of dollars in local manufacturing and port development.

Some wind-energy advocates have criticized BOEM’s 11th-hour call for the supplemental analysis as politically motivated and excessive.

Safe boat navigation and loss of fishing grounds are the main concerns among commercial fishermen, who have been the most vocal opponents of the 84-turbine Vineyard Wind project and other planned wind facilities off the coast of southern New England.

Last month, Rhode Island state Sen. Susan Sosnowski, D-New Shoreham and South Kingstown, gave assurances that the Coast Guard will not be deterred from conducting search and rescue efforts around offshore wind facilities, as some fishermen have feared.

“The Coast Guard’s response will be a great relief to Rhode Island’s commercial fishermen,” Sosnowski is quoted in a recent story in The Independent. “We have many concerns regarding navigational safety near wind farms, and that was the biggest.”

The anticipated release of the BOEM report coincides with President Trump’s efforts to weaken environmental impact reviews for all energy proposals, including wind, coal, and natural gas. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews have slowed pipeline projects such as Keystone XL and, as of last summer, Vineyard Wind. Both industries praised the move to loosen environmental rules. Environmentalists, meanwhile, fear that the removal of terms such as “cumulative,” "direct," and "indirect" from NEPA’s directives will nullify future federal efforts to address the climate crisis.

Once the expanded environmental impact statement is released, BOEM will offer a comment period and hold public hearings

Stephens leaves Vineyard Wind

Barrington native and Providence resident Erich Stephens resigned at the end of 2019 from Vineyard Wind, a company he helped found in 2009 and is now co-owned by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. The original wind company was called Offshore MW. Prior to Vineyard Wind, Stephens was head of development for Bluewater Wind, one of the first U.S. offshore wind companies.

Stephens has considerable roots in Rhode Island. He attended Barrington High School and received his undergraduate degree from Brown University. He was founder and executive director of People’s Power & Light, now called the Green Energy Consumers Alliance. He was also a founding partner of Solar Wrights, a residential solar company that was based in Barrington and moved to Bristol. The company was later acquired by Alteris Renewables. Stephens also worked for two of Rhode Island’s first oyster farms.

More megawatts

New York plans to add 1,000 megawatts of offshore wind power to the 1,700 megawatts it awarded last summer to offshore wind projects that will deliver electricity to Long Island and New York City.

The state also announced it’s taking bids for $200 million in port development projects that will support the offshore wind industry.

The recent notifications are part of the state’s Green New Deal, which aims for 9 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035 and 20 large solar arrays, battery-storage facilities, and onshore wind turbines in upstate New York. The state aims for 100 percent renewable energy by 2040.

The latest offshore wind projects consist of the 880-megawatt Sunrise Wind facility, developed by Ørsted and Eversource Energy, to power Manhattan. Long Island will receive up to 816 megawatts from the Empire Wind facility, developed by Equinor of Norway.

Pricing for the projects hasn’t been made public.

Offshore leader

Based in Denmark, Ørsted is the early leader in the size and number of U.S. offshore wind projects. Ørsted was awarded the 400-megawatt Revolution Wind project for Rhode Island. It’s also developing the 1,100-megawatt Ocean Wind facility in New Jersey, a demonstrations project in Virginia, and projects in Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Maryland. The company acquired Providence-based Deepwater Wind in 2018 for $510 million.

Ocean Wind, New Jersey’s first offshore wind project, and the 120-megawatt Skipjack Wind Farm off Maryland will use General Electric’s huge 12-megawatt Haliade-X turbines. The 853-foot-high turbines are the tallest in production and have twice the capacity of the 6-megawatt GE turbines now spinning off Block Island, which are 600 feet tall.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

Explosive dependence

Gas-valve cover in Boston.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

The recent natural-gas emergency on Aquidneck Island calls to mind the need for New England to accelerate its slow move away from polluting and flammable (and, in the case of gas, explosive) fossil fuel brought from far away and toward local renewable sources, which means mostly wind and solar power. Of course, this will require steady improvement in battery technology and much new construction, onshore and offshore. Ultimately, electricity from these sources will provide all of the electricity needed to run our homes, including heat, and do it cleanly.

Making New England less dependent on fossil fuel is not only good for the environment but it strengthens its economy by making it more energy-independent. And consider that the companie

Meanwhile there’s the good news that commercial fishermen are talking with Orsted U.S. Offshore Wind (which took over Deepwater Wind) on how to ease the interactions between offshore wind companies and the fishermen. The fishermen’s group is called the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance and represents fishermen from Maine to North Carolina.

While recreational fishermen tend to like the sort of offshore wind operation that’s up off Block Island because the wind-turbine supports act as reefs that lure fish, commercial fishermen are leery that wind farms will limit their ability to move around. Their fears are exaggerated but must be addressed. Of course, they, too, would benefit from the fact that wind farms tend to attract fish.

What the fishermen should really worry about is the Trump administration’s push for drilling for oil and gas off the East Coast. While a big offshore wind farm might inconvenience some commercial fishermen, think about what a big oil spill would do….

Spinning blades of offshore wind turbines found to create little noise

Block Island Wind Farm.

From eco RI News (ecori.org)

New research lead by the University of Rhode Island has concluded that offshore wind facilities produce minimal noise above and in the water while the blades are spinning. But the noise and vibrations from building them are a concern.

The research, funded through the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, began with the construction of Deepwater Wind’s Block Island Wind Farm in September 2015. It continued when the five turbines began spinning in late 2016.

Through acoustic monitoring, James Miller, URI professor of ocean engineering and an expert on ocean sound propagation, found that the sound from the turbines was barely detectable underwater.

“You have to be very close to hear it. As far as we can see, it’s having no effect on the environment, and much less than shipping noise,” Miller said.

Working with a team of specialists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Marine Acoustics Inc. of Newport, and others, Miller heard ships, whales, wind, and fish. But noise measurements 50 meters from the turbines was hardly audible. Above the waterline, the swish of blades was barely heard, according to Miller.

The noise was monitored using hydrophones in the water and geophones, which measure the vibration of the seabed, on the seafloor.

The vibrations from the pile driving of the turbine’s support structure is a bigger unknown. Miller said the vibrations on the seabed had a surprising intensity that may harm bottom-dwelling organisms such as flounder and lobsters, which have a huge economic value in the state.

“Fish probably can’t hear the noise from the turbine operations, but there’s no doubt that they could hear the pile driving,” Miller said. “And the levels are high enough that we’re concerned.”

To minimize the aquatic impacts, the pile driving started with minimal sound to allow marine life to move away. Pile driving was also prohibited between Nov. 1 and May 1 to protect migrating North Atlantic right whales, which are critically endangered. The pile driving was also limited to daytime so that spotters could search for nearby whales.

This kind of monitoring will continue once construction starts on other Deepwater Wind offshore wind farms such as the Skipjack Wind Farm, off the coast of Ocean City, Md. Additional research will be conducted in the federal offshore wind energy area between Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

In addition to the acoustic impacts, the researchers looked at the impacts of offshore wind facility construction and operations on fishing, habitats and seabed scaring and healing. Studies will eventually be published from that research.

URI expects to study and provide data for the nearly 1,000 offshore wind turbines that have been proposed for installation in the waters between Massachusetts to Georgia in the coming years.

“We’ve become the national experts, which has added to Rhode Island’s reputation as the Ocean State,” Miller said.