Martha Bebinger: Can pediatricians do more to stop drug overdoses?

— Photo by Martha Bebinger, WBUR

From Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Health News

(This article is from a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR, and KFF Health News.)

BOSTON

A 17-year-old boy with shaggy blond hair stepped onto the scale at Tri-River Family Health Center in Uxbridge, Massachusetts.

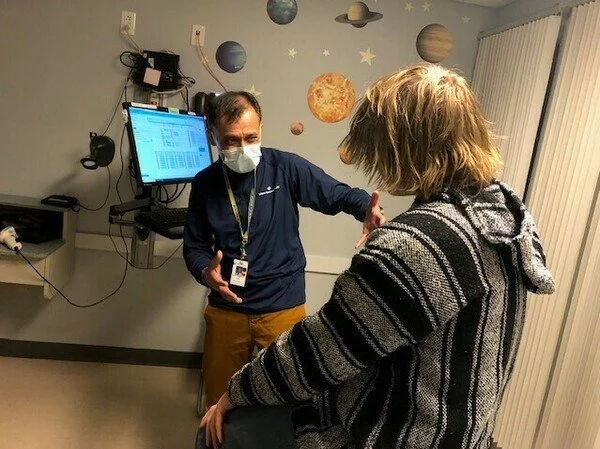

After he was weighed, he headed for an exam room decorated with decals of planets and cartoon characters. A nurse checked his blood pressure. A pediatrician asked about school, home life and his friendships.

This seemed like a routine teen checkup, the kind that happens in thousands of pediatric practices across the U.S. every day — until the doctor popped his next question.

“Any cravings for opioids at all?” asked pediatrician Safdar Medina. The patient shook his head.

“None, not at all?” Medina asked again, to confirm.

“None,” said the boy, named Sam, in a quiet but confident voice.

Only Sam’s first name is being used for this article because if his full name were publicized he could face discrimination in housing and job searches based on his prior drug use.

Medina was treating Sam for an addiction to opioids. He prescribed a medication called buprenorphine, which curbs cravings for the more dangerous and addictive opioid pills. Sam’s urine tests showed no signs of the Percocet or OxyContin pills he had been buying on Snapchat, the pills that fueled Sam’s addiction.

As part of his pediatric practice, Safdar Medina treats opioid use disorder. During a recent appointment at a clinic in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, Medina switched a teenage patient’s buprenorphine prescription to an injectable form and checked in about his school and social life.

“What makes me really proud of you, Sam, is how committed you are to getting better,” said Medina, whose practice is part of UMass Memorial Health.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends offering buprenorphine to teens addicted to opioids. But only 6% of pediatricians report ever doing do, according to survey results.

In fact, buprenorphine prescriptions for adolescents were declining as overdose deaths for 10- to 19-year-olds more than doubled. These overdoses, combined with accidental opioid poisonings among young children, have become the third-leading cause of death for U.S. children.

“We’re really far from where we need to be and we’re far on a couple of different fronts,” said Scott Hadland, the chief of adolescent medicine at Mass General for Children and a co-author of the study that surveyed pediatricians about addiction treatment.

That survey showed that many pediatricians don’t think they have the right training or personnel for this type of care — although Medina and other pediatricians who do manage patients with addiction say they haven’t had to hire any additional staff.

Some pediatricians responded to the survey by saying they don’t have enough patients to justify learning about this type of care, or don’t think it’s a pediatrician’s job.

“A lot of that has to do with training,” said Deepa Camenga, associate director for pediatric programs for the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, in New Haven, Conn. “It’s seen as something that’s a very specialized area of medicine and, therefore, people are not exposed to it during routine medical training.”

Camenga and Hadland said medical schools and pediatric residency programs are working to add information to their curricula about substance use disorders, including how to discuss drug and alcohol use with children and teens.

But the curricula aren’t changing fast enough to help the number of young people struggling with an addiction, not to mention those who die after taking just one pill.

In a twisted, deadly development, drug use among adolescents has declined — but drug-associated deaths are up.

The main culprits are fake Xanax, Adderall or Percocet pills laced with the powerful opioid fentanyl. Nearly 25% of recent overdose deaths among 10- to 19-year-olds were traced to counterfeit pills.

“Fentanyl and counterfeit pills is really complicating our efforts to stop these overdoses,” said Andrew Terranella, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s expert on adolescent addiction medicine and overdose prevention. “Many times these kids are overdosing without any awareness of what they’re taking.”

Terranella said pediatricians can help by stepping up screening for — and having conversations about — all types of drug use.

He also suggests that pediatricians prescribe more naloxone, the nasal spray that can reverse an overdose. It’s available over the counter, but Terranella, who practices in Tucson, Arizona, believes a prescription may carry more weight with patients.

Back in the exam room, Sam was about to get his first shot of Sublocade, an injection form of buprenorphine that lasts 30 days. Sam is switching to the shots because he didn’t like the taste of Suboxone, oral strips of buprenorphine that he was supposed to dissolve under his tongue. He was spitting them out before he got a full dose.

Many doctors also prefer to prescribe the shots because patients don’t have to remember to take them every day. But the injection is painful. Sam was surprised when he learned that it would be injected into his belly over the course of 20-30 seconds.

“Is it almost done?” Sam asked, while a nurse coaches him to breathe deeply. When it was over, staffers joked out loud that even adults usually swear when they get the shot. Sam said he didn’t know that was allowed. He’s mostly worried about any residual soreness that might interfere with his evening plans.

“Do you think I can snowboard tonight?” Sam asked the doctor.

“I totally think you can snowboard tonight,” Medina answered reassuringly.

Sam was going with a new buddy. Making new friends and cutting ties with his former social circle of teens who use drugs has been one of the hardest things, Sam said, since he entered rehab 15 months ago.

“Surrounding yourself with the right people is definitely a big thing you want to focus on,” Sam said. “That would be my biggest piece of advice.”

For Sam, finding addiction treatment in a medical office jammed with puzzles, toys and picture books has not been as odd as he thought it would be.

He mother, Julie, had accompanied him to this appointment. She said she’s grateful that the family found a doctor who understands teens and substance use.

Before he started visiting the Tri-River Family Health Center, Sam had seven months of residential and outpatient treatment — without ever being offered buprenorphine to help control cravings and prevent relapse. Only 1 in 4 residential programs for youth offer it. When Sam’s cravings for opioids returned, a counselor suggested Julie call Medina.

“Oh my gosh, I would have been having Sam here, like, two or three years ago,” Julie said. “Would it have changed the path? I don’t know, but it would have been a more appropriate level of care for him.”

Some parents and pediatricians worry about starting a teenager on buprenorphine, which can produce side effects including long-term dependence. Pediatricians who prescribe the medication weigh the possible side effects against the threat of a fentanyl overdose.

“In this era, where young people are dying at truly unprecedented rates of opioid overdose, it’s really critical that we save lives,” said Hadland. “And we know that buprenorphine is a medication that saves lives.”

Addiction care can take a lot of time for a pediatrician. Sam and Medina text several times a week. Medina stresses that any exchange that Sam asks to be kept confidential is not shared.

Medina said treating substance-use disorder is one of the most rewarding things he does.

“If we can take care of it,” he said, “We have produced an adult that will no longer have a lifetime of these challenges to worry about.”

Martha Bebinger is a WBUR reporter.

Uxbridge Congregational Church and Civil War monument.

Mass. lawsuit unveils aspects of how the Sackler family reaped a vast fortune off OxyContin

The Sackler family, famously obsessed with raising their social status, have given most of their charitable gifts to already rich elite institutions. Here, for example, is the Sackler Building at Harvard.

By Christine Willmsen, WBUR and Martha Bebinger, WBUR

BOSTON

The first nine months of 2013 started off as a banner year for the Sackler family, owners of the pharmaceutical company that produces OxyContin, the addictive opioid pain medication. Stamford, Conn.-based Purdue Pharma paid the family $400 million from its profits during that time, claims a lawsuit filed by the Massachusetts attorney general.

However, when profits dropped in the fourth quarter, the family allegedly supported the company’s intense push to increase sales representatives’ visits to doctors and other prescribers.

Purdue had hired a consulting firm to help reps target “high-prescribing” doctors, including several in Massachusetts. One physician in a town south of Boston wrote an additional 167 prescriptions for OxyContin after sales representatives increased their visits, according to the latest version of the lawsuit filed Thursday in Suffolk County Superior Court in Boston.

The lawsuit claims Purdue paid members of the Sackler family more than $4 billion between 2008 and 2016. Eight members of the family who served on the board or as executives as well as several directors and officers with Purdue are named in the lawsuit. This is the first lawsuit among hundreds of others that were previously filed across the country to charge the Sacklers with personally profiting from the harm and death of people taking the company’s opioids.

WBUR along with several other media sued Purdue Pharma to force the release of previously redacted information that was filed in the Massachusetts Superior Court case. When a judge ordered the records to be released with few, if any, redactions this week, Purdue filed two appeals and lost.

The complaint filed by Massachusetts Atty. Gen. Maura Healey says that former Purdue Pharma CEO Richard Sackler allegedly suggested the family sell the company or, if they weren’t able to find a buyer, to milk the drugmaker’s profits and “distribute more free cash flow” to themselves.

That was in 2008, one year after Purdue pleaded guilty to a felony and agreed to stop misrepresenting the addictive potential of its highly profitable painkiller, OxyContin.

At a board meeting in June 2008, the complaint says, the Sacklers voted to pay themselves $250 million. Another payment in September totaled $199 million.

The company continued to receive complaints about OxyContin similar to those that led to the 2007 guilty plea, according to unredacted documents filed in the case.

While the company settled lawsuits in 2009 totaling $2.7 million brought by family members of those who had been harmed by OxyContin throughout the country, the company amped up its marketing of the drug to physicians by spending $121.6 million on sales reps for the coming year. The Sacklers paid themselves $335 million that year.

The lawsuit claims that Sackler family members directed efforts to boost sales. An attorney for the family and other board directors is challenging the authority to make that claim in Massachusetts. A motion on jurisdiction in the case hasn’t been heard. That attorney hasn’t responded to a request for comment on the most recent allegations.

Purdue Pharma, in a statement, said the complaint filed by Healey is “part of a continuing effort to single out Purdue, blame it for the entire opioid crisis, and try the case in the court of public opinion rather than the justice system.”

Purdue went on to charge Healey with attempting to “vilify” Purdue in a complaint “riddled with demonstrably inaccurate allegations.” Purdue said it has more than 65 initiatives aimed at reducing the misuse of prescription opioids. The company says Healey fails to acknowledge that most opioid overdose deaths are currently the result of fentanyl.

Purdue fought the release of many sections of the 274-page complaint. Attorneys for the company said at a hearing on Jan. 25 that they had agreed to release much more information in Massachusetts than has been cleared by a judge overseeing hundreds of cases consolidated in Ohio. Purdue filed both state and federal appeals this week to block release of the compensation figures and other information about Purdue’s plan to expand into drugs to treat opioid addiction.

The attorney general’s complaint says that in a ploy to distance themselves from the emerging statistics and studies that showed OxyContin’s addictive characteristics, the Sacklers approved public marketing plans that labeled people hurt by opioids as “junkies” and “criminals.”

Richard Sackler allegedly wrote that Purdue should “hammer” them in every way possible.

While Purdue Pharma publicly denied its opioids were addictive, internally company officials were acknowledging it and devising a plan to profit off them even more, the complaint states.

Kathe Sackler, a board member, pitched “Project Tango,” a secret plan to grow Purdue beyond providing painkillers by also providing a drug, Suboxone, to treat those addicted.

“Addictive opioids and opioid addiction are ‘naturally linked,'” she allegedly wrote in September 2014.

According to the lawsuit, Purdue staff wrote: “It is an attractive market. Large unmet need for vulnerable, underserved and stigmatized patient population suffering from substance abuse, dependence and addiction.”

They predicted that 40-60 percent of the patients buying Suboxone for the first time would relapse and have to take it again, which meant more revenue.

Purdue never went through with it, but Attorney General Healey contends that this and other internal documents show the family’s greed and disregard for the welfare of patients.

This story is part of a reporting partnership between WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

A version of this story first ran on WBUR’s CommonHealth. You can follow @mbebinger on Twitter.