Chris Powell: On whom will pandemic resentments fall?

Representation of resentment

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Teachers and nurses in Connecticut who are government employees, along with employees of nursing homes, whose industry is mostly funded by government, are feeling so overworked because of the virus epidemic that their allegiance to Gov. Ned Lamont and the Democratic Party is coming into question.

Surveying leaders of the teachers and nurses unions last week, the Connecticut Post's Ken Dixon found no rebellion but little enthusiasm. Some union leaders acknowledged that state government had made special efforts for their members but insisted that more was owed to them. Prison workers weren't surveyed but might have expressed the greatest bitterness, since the prisons are full of virus cases.

But beyond government's employees and quasi-employees, parents of schoolchildren and relatives of people ailing with something other than the virus have resentments too. For the more safety measures are demanded by teachers and nurses, the less schooling will be delivered and the less medical care will be available to people afflicted with something other than the virus. Some people whose treatment was delayed have died.

While teachers and nurses think of themselves as workplace martyrs to the epidemic, they are hardly alone.

Restaurants, bars, and the rest of the hospitality industry have been devastated. Even when restaurants and bars have been allowed to reopen, many customers have stayed away.

Retailers have been devastated too, as personal incomes were cut throughout the nation by a decline in working hours. Even when hours were restored, wages were overtaken by inflation, which in part is a result of the government's distributing so much free money even as millions of people have stopped working and producing things to buy.

Amid the hysteria of the government and news organizations, which treat even asymptomatic virus cases as the plague, workers in all sectors of the economy increasingly call out sick. This hobbles far more than schools, as society discovers that school bus drivers and trash haulers are really "essential workers" too.

Are those electrons over the state capitol dome?

There may be only one set of workers who are neither overworked nor forced to sacrifice income and benefits: employees of the government bureaucracy, many of whom, in Connecticut, are allowed to work from home most of the time, pushing electrons when they are not pushing paper.

In the name of "solidarity forever" could these employees sacrifice a little income or time on the job in favor of the government employees and quasi-employees who are overwhelmed in schools, hospitals, and nursing homes? Of course not; the paper and electron pushers will insist on every last cent of their wages and every last restriction on their working conditions as promised by their union contract. And since the paper and electron pushers are represented by unions affiliated with the unions of the teachers and nurses, the teachers and nurses will give them a pass anyway -- in the name of "solidarity forever."

So now that the epidemic in Connecticut is suddenly worsening after fading for many months, on whom should the state's political resentments fall?

The Communist government of China might be the place to start, since the virus may have originated from bio-weapons research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. But Americans can't vote for the Chinese government; even the Chinese themselves can't.

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has gotten off easy for funding research at the Wuhan laboratory. Americans might be tired of Fauci, but he's not elected either.

President Biden ordinarily would be a prime target of resentment, but as he dodders ineffectually from day to day -- spending a quarter of his time away from the office, apparently to regain his senses -- what would be the point of bashing him?

That leaves Governor Lamont, who got all the credit when the epidemic was fading and who is up for re-election this year and thus the most available target. At least Lamont didn't constantly make a mess of things as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio did, but how much enthusiasm will be sparked by a campaign slogan like "It Could Have Been Worse"?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Don Pesci: Representative government crouched in fear

Painting by Peter Paul Rubens of Cronus devouring one of his children

VERNON, Conn.

The Hartford Courant paper points out the brutal irony:

“Connecticut has averaged 366 new cases a day over the past week or about 10.3 per 100,000 residents, just above the threshold at which states are added to the travel advisory. The advisory, which currently includes 38 states and territories, is updated each Tuesday in conjunction with New York and New Jersey. It requires travelers arriving from those states to either produce a negative coronavirus test result or quarantine for 14 days...

(Connecticut Gov. Ned) Lamont said …he’s considering a dramatic overhaul to the advisory, saying “It’d be a little ironic if we were on our own quarantine list.”

Connecticut’s list of quarantined states has grown by leaps and bounds, very likely because the parameters initially were set too low. The gods of irony will not be mocked. Cronus is now eating his own children.

It is nearly impossible to determine definitively who set the parameters, but we do know that Governor Lamont has been borrowing his Coronavirus defense system from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy.

In the absence of an advice-and-consent General Assembly whose Democrat leaders, Senate President Martin Looney and House Speaker Joe Arsimowicz, relish pretending that Connecticut’s greatest deliberative body had been sidelined by Coronavirus, Lamont has become the King George of Connecticut, wielding nearly absolute power, and the sharpest weapon in Lamont’s rhetorical arsenal has been – fear of Coronavirus.

The pandemic is not a governor festooned with plenary powers. It is a virus, and viruses cannot suspend the operations of government and businesses across the state. We are where we are because politicians have made the choices they have made.

Gone are the days when President Franklin Roosevelt sought to stiffen American spines, first in the face of the Great Depression and then of the oncoming World War II – by advising his countrymen, “… let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is...fear itself.”

Americans rose to the occasion. The Great Depression receded, as most depressions and recessions will do in a vibrant free market economy. The United States later officially entered the war on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor -- more than two years after Nazi Germany attacked Poland, in 1939, beginning the war -- and saved Western Europe from the Nazi Hun. Much later during the so-called “Cold War,” beginning in 1946-47, Western Europe and the United States combined to save Western Civilization from the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist beast. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan blew his horn, and the hated Berlin Wall soon came tumbling down, followed in due course by the dissolution of the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe.

Since the Founders “brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty,” in Lincoln’s often repeated words, the United States has survived colonial mismanagement – see Sam Adams on the point – an anti-colonialist revolution, various crippling recessions, a Civil War – which we thought, before Howard Zinn’s dyspeptic take on American history began to infiltrate public schools, buried slavery along with “the honored dead” at Gettysburg -- two World Wars, the prospect of nuclear annihilation, and many other disrupting disasters that we had collectively survived.

The government of Connecticut, the “Constitution State”, faced with Coronavirus, has simply shattered. And the merchants of fear among us are still merchandising fear. That irrational fear has all but destroyed scores of small businesses across the state, the prospect of state surpluses, sound state and municipal budgets, public hearings, trials in the remnant of the state’s judicial system, public education as we have known it ever since the General Assembly in 1849 established the first public higher-education institution in the state, now Central Connecticut State University -- and representative government.

There is not a single politician in Connecticut familiar with Aristotelian causality, the living root of most modern science, who would testify under oath that a virus, rather than cowardly politicians, is the efficient cause of all these problems. The Coronavirus fear, like Cronus of Greek legend, is now devouring its own children.

Roosevelt rallied the nation to stop hiding under the bed. But the Coronavirus governors, who through their negligence are responsible for the majority of nursing-home deaths associated with Coronavirus in their own states, want representative government to remain crouched in fear under the bed. They want no public hearings, no votes on gubernatorial dicta by a full General Assembly, no attacks by columnists on their own criminal delinquencies, no suits in a crippled court system, and no contrarian opinions in editorial pages. They will tolerate no effective opposition. And should minority Republicans in Connecticut engage in reasoned opposition, they will be denounced by everyone hiding under a bed of complicity with President Trump who, despite his glaring vices, still is not Hunter Biden’s dad.

Don Pesci is a columnist based in Vernon.

James E. Varner: Trump tool DeJoy assaults Postal Service

The U.S. Post Office in the old mill village of Whitinsville, Mass., part of the town of Northbridge. Like many attractive post offices, it was built as part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration. Opened in 1938, it’s a Colonial Revival masonry building, built of brick and cast stone, capped by a hip roof and cupola and with pilasters flanking the central entrance.

Via OtherWords.org

President Trump’s postmaster general, Louis DeJoy, recently testified before Congress about major slowdowns in mail delivery under his watch.

As a 20-year postal veteran, I had only one reaction: DeJoy needs to be Returned to Sender.

DeJoy, a Trump fundraiser who owns millions worth of stock in U.S. Postal Service competitors, has been on the job barely two months. But already, his changes have caused serious delays in delivery.

Ostensibly, these moves are cost-saving measures. But it doesn’t take a partisan cynic to understand how this kind of disruption could affect voting in November’s election. The president himself has said that he hopes as much.

Postal employees pride ourselves on a culture of never delaying the mail. Our unofficial mantra can best be summed up as, “Mail that comes in today, goes out today — no matter what.”

We are now being told to ignore that. If mail can’t get delivered or processed without overtime, it is supposed to sit and wait. That can mean big delays.

For example, letter carriers normally split up the route of a colleague who’s on vacation or out sick. These carriers each take a portion of the absent employee’s route after completing their own, often using a little bit of overtime. Now, that mail doesn’t get delivered until much later.

Then there’s the mail that arrives late in the day. Before, late arriving mail would often be processed for the next day’s delivery, even if that required the use of overtime. Today, that mail sits in the plant at least until the following evening. Mail arriving late on a Saturday or a holiday weekend could be delayed even longer.

In the plants, meanwhile, the short staffing of clerks means it takes longer to get all the mail through the sorting machines. To make matters worse, under orders from DeJoy, mail-processing equipment is also being scrapped.

Even though the processing takes longer, drivers aren’t allowed to wait on it. Postal truck drivers are being disciplined for missing their departure time even by a few minutes — even if they haven’t gotten all the mail they’re supposed to haul. In some cases, the trucks that leave are completely empty!

With package deliveries up by 50 percent during the pandemic, as the Institute for Policy Studies reports, large mail trucks operating between facilities are often already full. Imagine how much mail will get left behind when that’s combined with seasonal holiday mail, or a large number of absentee ballots.

Finally, DeJoy’s proposals to cut hours of operation at many smaller post offices — and the removal of many public mailboxes — will make it harder for the public to access postal services.

When you limit hours to 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. and close on Saturdays, you eliminate access for anybody working the day shift. Throw in mandatory closure for lunch breaks in the middle of the day, and it makes matters that much worse for our customers.

Postal workers have been doing their best to keep the nation’s mail and packages moving in these difficult and hazardous times. We don’t deserve these attacks.

DeJoy now says he’ll delay more changes until after the election, but he also had the nerve to tell Congress that he wouldn’t replace the 600 sorting machines he’d already removed.

Delaying more changes isn’t enough. Instead, Congress must approve crisis relief for USPS — and reverse DeJoy’s disastrous service cuts altogether.

James E. Varner is the director of Motor Vehicle Service at American Postal Workers Union Local 443 in Youngstown, Ohio. This op-ed was adapted from a letter published in the Warren Tribune-Chronicle.

David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

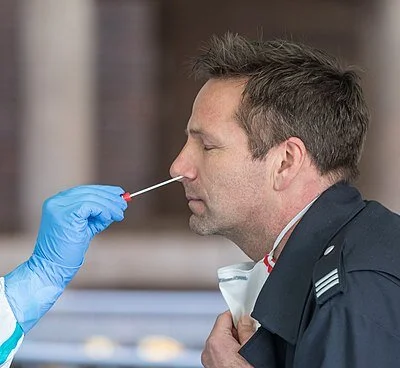

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Jill Richardson: Stay at home and stay angry

Via OtherWords.org

Social distancing is hard, and it’s not fun.

I don’t question that we are doing what is necessary. Until better testing, treatment, and prevention are available, it is. But quarantining us in our homes separates us at a time when we need connection.

And you know what? It’s okay to feel angry about that. It’s important to remember we’re doing this in part because the people at the top screwed up.

Trump fired the pandemic response team two years ago, even though Obama’s people warned them that we needed to work on preparedness for exactly this in 2016. Unsurprisingly, a government simulation exercise just last year found we were not prepared for a pandemic.

Later on, even after the disease had come to the U.S., infectious disease experts in Washington State had to fight the federal government for the right to test for the coronavirus.

It gets worse.

Now we know that North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr was taking the warnings seriously weeks before any real action was taken — and all he did was sell off a bunch of stock, while telling the public everything was fine. Meanwhile, Trump didn’t want a lot of testing, because he wanted to keep the number of confirmed cases low to aid his re-election.

The people we trusted to keep us safe didn’t do that. Now the entire economy’s turned upside down, people are dying, and we’re all cooped up at home.

It sucks. We should be angry.

I’m young enough that I probably don’t have to worry much about the likelihood of a serious case if I get sick. But I’m staying home, because I don’t want to get it and accidentally spread it to someone more vulnerable than myself.

I’m also aware of the sacrifice that many of us are making for the sake of others. Some lost their jobs, while others put themselves at risk working outside the home because they can’t afford not to — or, in the case of health care workers, because they’re badly needed.

Entire families are cooped up together and I’ve heard jokes that divorce lawyers will get plenty of business after this. Parents are posting memes about how much they appreciate teachers now that they are stuck with their kids all day. I’m entirely alone besides a cat.

I worry about the college seniors graduating this year and trying to find a job. What about people prone to anxiety and depression? How much will this exacerbate domestic abuse? What about people in jails, prisons, and detention centers?

Our society is deeply unequal. So while the virus itself doesn’t discriminate, this bigger crisis will hit people unequally. Some don’t have health insurance. Some are undocumented. Some are more susceptible to dying from the disease.

The people in power who screwed up are wealthy enough that they can work from home, maintain their income, and access affordable health care. Others will feel the full brunt of this, not them. It’s not fair.

I’m supportive of doing all we can to prevent the virus’s spread and to protect vulnerable people, but anger at the people whose incompetence put us in this position is justified. We deserve better.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is an OtherWords.org columnist.

Ready for a pandemic?

Warning signs at DeGaulle Airport, the Paris region’s primary airport

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Back in 2003 I flew to Taiwan (one of my favorite nations) during the epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome— the SARS virus that started, as do so many viruses, in very crowded China. Inconveniently, I was coming out of a bad cold, with bronchitis, and was doing my fair share of coughing on the plane, most of whose passengers were wearing face masks (even without a public-health threat like SARS, many East Asians wear face masks as a matter of course). My coughing clearly distressed my fellow passengers; some moved to vacant seats further away from me.

So I feared that I’d be stopped at the Taipei airport and quarantined for 10 days. Luckily, my guide (who told me “no worries!”) for the series of meetings I had planned for my week on the island, managed to get me through -- or was it around? -- the passport and other controls, and the week went well as my cough subsided. I didn’t have SARS, and the epidemic was eventually stopped after some weeks.

The experience impressed on me how fast epidemics can spread in a time of international jet travel, ever-bigger cities (especially in the Developing World) and, particularly in much of Asia, because of the close proximity of hundreds of millions of people to domesticated and wild animals that can carry dangerous viruses that can rapidly mutate and threaten humans. Still, there’s hope that the decline in the number of rural (and not so rural) Chinese keeping pigs, poultry and other animals in their backyards as the country becomes more urbanized might reduce the spread of dangerous viruses. And of course medicine marches on.

But it seems inevitable that a true worldwide virus pandemic will eventually kill millions.

How ready are we? The World Health Organization, part of the United Nations, needs more resources to plan for and coordinate the battle against epidemics. (By the way, Taiwan is not a member of the WHO; it only has “observer’’ status because China, throwing its weight around in its claim that it owns the island democracy, keeps it out.)

The U.N. hosts assorted hypocrisies, idiocies and corruptions. But real and threatened epidemics is just one huge reason why we need it.

And the Trump administration, which doesn’t particularly like international coordination, has shut down an office charged with responding to global pandemic threats, curtailed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s foreign-disease-outbreak-prevention efforts and ended a surveillance program set up to detect new viral threats. Perhaps it will reconsider in an election year.