Chris Powell: Abolish government pensions

New Haven Police Chief Otoniel Reyes is “retiring” at age 49 with a $117,000-a-year pension to move to nearby Quinnipiac University, where he’ll run the campus police at a salary that will probably be around $170,000.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut should prohibit pensions for state and municipal government employees, not because they are bad people or especially undeserving but for several solid policy reasons.

First, most of the taxpayers who pay for those pensions don't enjoy anything like them.

Second, state and municipal government can't be trusted to fund the pensions adequately.

And third, the pension system for state and municipal employees separates a huge and politically influential group from Social Security, the federal pension system on which nearly everyone else relies, and thus weakens political and financial support for it.

Connecticut state government has an estimated $60 billion in unfunded liabilities in its state-employee and municipal-teacher pension funds. But after attending the recent meeting of the state General Assembly's finance committee, Yankee Institute investigative reporter Marc Fitch wrote that another $900 million in unfunded liabilities are sitting in New Haven's pension funds.

According to Fitch, New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker testified about the city's pension-fund disaster, noting that city government faces a projected $66 million deficit in its next budget and that pension obligations are a major cause of it.

Of course the mayor attended the hearing to beg more money from state government for the city. Unfortunately no legislator seems to have asked Elicker about the $117,000 annual pension that the city is about to start paying its police chief, Otoniel Reyes, so that he can "retire" at age 49 to take a job with Quinnipiac University, in nearby Hamden, Conn., probably at a salary around $170,000, and begin earning credit toward a second luxurious pension. Indeed, no news organization in New Haven seems to have even reported the chief's premature pension yet.

Maybe legislators didn't ask about the "retiring" chief's pension because state government has been just as incompetent and corrupt with pensions as New Haven city government. These enormous and incapacitating unfunded liabilities are proof of political corruption and incompetence at both the state and city levels -- the promising of unaffordable benefits to a politically influential special interest.

Connecticut's tax system may be unfair, but it's not why New Haven is insolvent. Like state government, the city is insolvent because it has given too much away.

Government in Connecticut is good at clearing snow from the streets and highways because failure there is immediately visible. But beyond snowplowing government, in Connecticut is not much more than a pension and benefit society whose operation powerfully distracts from serving the public.

This distraction should be eliminated, phased out as soon as government recognizes that it has higher purposes than the contentment of its own employees.

xxx

Proposing his new state budget this month, Governor Lamont announced plans to close three of Connecticut's 14 prisons in response to the decline of nearly 50 percent in the state's prison population over the last decade.

A few days later New Haven's Board of Alders asked Assistant Police Chief Karl Jacobson to explain the recent explosion of violent crime in the city.

According to the New Haven Register, the assistant chief said there were 73 gang-related shootings in the city in 2020 against only 41 in 2019 and 32 in 2018. Murders in the city so far this year total seven, against none in the same period last year. So far this year there have been 12 shootings in the city, up from five at this time last year, and 36 shooting incidents this year compared to 20 at this time last year.

As usual, the assistant chief said, a big part of the violence in the city involves men recently released from prison who resume feuds and otherwise are prone to get into trouble. The police plan to hold preventive meetings with such men, and the city has just opened a "re-entry center" for new parolees.

The explosion of crime in New Haven, Hartford, Bridgeport and other cities does not sound like cause to close prisons. It sounds like cause to investigate prison releases and the failure of criminal rehabilitation.

Maybe the General Assembly would undertake such investigation if the former and likely future offenders were delivered to suburbs instead of cities. Then saving money by closing prisons might not be considered such a boast.

xxx

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Philip K. Howard: Create panel to streamline government in wake of virus, including fixing extreme pensions, work rules

Worker disinfects a New York City subway car in the current pandemic. New York State’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority operations are rife with astronomically expensive and outdated work rules and extravagant pensions. Ditto at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

NEW YORK

Howls of outrage greeted Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s (R.-Ky.) suggestion that Congress should resist further funding of insolvent state and local governments because the money would be used “to bail out state pensions” that were never affordable except “by borrowing money from future generations.” Instead, Senator McConnell suggested, perhaps Congress should pass a law allowing states to declare bankruptcy.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo immediately countered that the bankruptcy of a large state would lead to fiscal chaos, and called McConnell’s suggestion “one of the saddest, really dumb comments of all time.”

Indeed, the lesson of the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy was that a bail-out would have been far preferable, less costly as well as less disruptive to markets.

But McConnell is correct that many states are fiscally underwater because of irresponsible giveaways to public unions. About 25 percent of the Illinois state budget goes to pensions, including more than $100,000 annually to 19,000 pensioners, who retired, on average, at age 59. These pensions were often inflated by gimmicks such as spiking overtime in the last years of employment, or by working one day to get credit for an extra year.

In New York, arcane Metropolitan Transportation Authority work rules result in constant extra pay — including an extra day’s pay if a commuter rail engineer drives both a diesel and an electric train; two months of paid vacation, holiday and sick days; and overtime for workdays longer than eight hours even if part of a 40-hour week. In 2019, the MTA paid more than $1 billion in overtime.

Cuomo has thrown out rulebooks to deal with COVID-19, and recently mused about the need to clean house: “How do we use this situation and …reimagine and improve and build back better? And you can ask this question on any level. How do we have a better transportation system, a …better public health system… You have telemedicine that we have been very slow on. Why was everybody going to a doctor's office all that time? Why didn't you do it using technology? … Why haven't we incorporated so many of these lessons? Because change is hard, and people are slow. Now is the time to do it.”

Cut red tape, reform entitlements

Perhaps McConnell and Cuomo are not that far apart after all. While bankruptcy makes no sense now, since states can hardly be blamed for COVID-19, federal funding could come with an obligation by states to adopt sustainable benefits and work practices for public employees.

Why should taxpayers pay for indefensible entitlements? How can Cuomo run “a better transportation system” when rigid work rules prohibit him from making sensible operational choices?

Taxpayers are reeling from these indefensible burdens. The excess baggage in public institutions is hardly limited to public employees. The ship of state founders under the heavy weight of red tape and entitlements that have, at best, only marginal utility to current needs.

Bureaucratic paralysis is the norm, whether to start a new business (the U.S. ranks 55th in World Bank ratings) or to act immediately when a virulent virus appears (public health officials in Seattle were forced to wait for weeks for federal approvals).

Well-intended programs from past decades have evolved into inexcusable entitlements today — such as “carried interest” tax breaks to investment firms and obsessive perfection mandated by special-education laws (consuming upward of a third of school budgets).

Partisanship blocks reform

Government needs to become disciplined again, just as in wartime. It must be adaptable, and encourage private initiative without unnecessary frictions. Dense codes should be replaced with simpler goal-oriented frameworks, as Cuomo has done. Red tape should be replaced with accountability. Excess baggage should be tossed overboard. We’re in a storm, and can’t get out while wallowing under the heavy weight of legacy practices and special privileges.

McConnell and Cuomo each have identified the madness of tolerating public-waste-as-usual. But toxic partisanship drives them apart. Nor would ad hoc negotiations work to restore discipline to government; too many interest groups feast at the public trough.

The only practical approach is for Congress to authorize an independent recovery commission with a broad mandate to relieve red tape and recommend ways to clean out unnecessary costs and entitlements. This is the model of “base-closing commissions” that make politically difficult choices of which states lose military bases.

Recovering from this crisis will be difficult enough without lugging along the accumulated baggage from the past. A streamlined, disciplined government would be a godsend not only to marshal resources for social needs, but to liberate human initiative at every level of society. That requires changing the rules. But change is hard, as Cuomo noted. Broad trust will be needed. That’s why the new framework should be devised by an independent recovery commission. =

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, writer, civic leader and photographer, is founder of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward. This piece first ran in USA Today.

James P. Freeman: R.I.'s moderate Democrat Gina Raimondo a very consequential governor

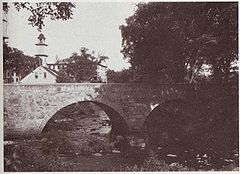

The Slatersville Stone Arch Bridge, in the old Blackstone River Valley industrial zone.

For more than 200 years water has flowed underneath a bridge in North Smithfield, in the Blackstone Valley corridor of the smallest state in the Union, which helped usher in the American Industrial Revolution. The Slatersville Stone Arch Bridge, the oldest masonry bridge in Rhode Island -- built in 1855 to replace the original wooden structure and subsequently listed on the National Register of Historic Places – was for decades neglected and structurally deficient. Now it’s undergoing a complete rehabilitation at a $13.5 million cost. The bridge is symbolic of the state’s rise and fall. And now its revival.

Much of that effort is being spearheaded by Gov. Gina Raimondo.

Amidst the partisan tempest -- The Great Political Uncentering -- Raimondo, 46, the state’s first female executive, stands in defiance of political trends. And recent history. She’s seeking re-election this year, after a record of public service that has been a series of calculated experiments. She is arguably the nation’s most consequential reform-minded, results-oriented politician. She is resuscitating a nearly extinct species -- Truman Democrats. She is a pro-growth moderate and has handled heavy turbulence.

For an insular and provincial state -- where coffee milk is the official drink, Catholic Mass is still televised on Sunday mornings and, unbelievably, New England Cable News is not offered for viewing by the largest telecommunications provider -- the last decade was particularly cruel. Nothing went as planned and many plans went for nothing.

In the wake of The Great Recession of 2008-2009, Rhode Island’s already corroded economy saw unemployment spike close to 12 percent while housing prices plunged 27 percent. In 2010, after luring it away from Massachusetts, the state financed Curt Schilling’s scandal-plagued video-game start-up, 38 Studios, with $75 million in bonds before the company went bankrupt, two years later. And in 2011, sparking national headlines, Central Falls, a city with a population of 19,376, covering an area a little over a square mile (more densely populated than Boston), filed for bankruptcy, raising concerns that other heavily encumbered municipalities (including the capital, Providence) might follow suit.

Residents probably needed a professional psychologist to lead them out of their depressed state.

Instead, they chose a thoughtful capitalist. Raimondo -- a Rhode Island native with degrees in economics (Harvard), sociology (Oxford) and law (Yale), and co-founder of the state’s first venture-capital firm, Point Judith Capital -- was elected state treasurer in 2010. So began the secular resurrection.

Raimondo immediately understood a law of modern politics that most public officials refuse to acknowledge or act upon: Demographics is destiny.

Overly generous and ambitious, yet massively underfunded, pension assurances to Rhode Island’s aging population coupled with a rapidly hemorrhaging fiscal condition (exacerbated by the recession) were certain to wreak financial havoc. A series of cascading municipal failures would likely render the state itself technically insolvent. And that would be unchartered territory (a state declaring bankruptcy is not a contingency properly addressed under current bankruptcy laws). Raimondo foresaw that imminent horror.

So, the treasurer did something astounding. She conducted town-hall-style meetings exposing the severity of the crisis. And she told the unions and pensioners something that few Democrats ever say to those loyal constituents: “No!”

She engineered an overhaul by suspending cost-of-living increases and raising the retirement age for retirees, pointing the system towards solvency. Raimondo also understood state law. While many state pension systems are determined by contract (making modifications more difficult under constitutional law), Rhode Island’s, by statute, lets the government, if so inclined, make changes via swift legislative maneuvering, not protracted judicial wrangling.

It worked.

Predictably, though, public-sector unions fulminated and sued. A September 2014 Washington Post editorial noted, “In the face of ferocious opposition from labor, she explained the plain budgetary impossibility of maintaining pensions at the levels promised by politicians in Providence.”

Still, she was able to win the governorship that year with 41 percent of the vote in a three-way race. Later, in 2015, she negotiated legal settlements that preserved the reforms in the face of continued legal opposition. Her efforts are proof that pension reforms can be administered and may prove to be a model for other states suffocating under mountains of indebtedness.

Just after Raimondo was elected governor (the first Democrat in over 20 years to win the office despite Rhode Island being heavily Democratic) and after the national Republican congressional victory in 2014, The Daily Beast’s Joel Kotkin demanded that Democrats go back-to-the-future: “Time to Bring Back the Truman Democrats.”

“To regain their relevancy,” he hypothesized, “Democrats need to go back to their evolutionary roots. Their clear priorities: faster economic growth and promoting upward mobility for the middle and working classes. All other issues -- racial, feminine, even environmental -- need to fit around this central objective.”

Raimondo, perhaps instinctively, has embraced much of this sensible framework. Most of it via a back-to-basics moderate agenda. Actually, future-to-the-basics.

In February 2016, she launched Rhode Works, a comprehensive 10-year transportation improvement program to repair crumbling roads and bridges. Rhode Island ranked dead last (50 out of 50 states) in overall bridge condition and is one of the only states that did not charge user fees to large commercial trucks on its roadways, which do most of the damage to roads and bridges. Tolling on certain roads begins this winter. Unsurprisingly, she is facing more opposition. This time from trucking associations, leery of the legislation; claiming that they’re being unfairly discriminated against, they are threatening lengthy lawsuits. But her infrastructure initiative might be a template for the anticipated trillion-dollar federal program.

Raimondo has also looked north for much of her inspiration. It’s home to another moderate.

In her fourth State of the State address she made this startling admission: “For decades, we just sat back and watched as Massachusetts rebuilt and thrived. Boston and its suburbs flourished, while the mill buildings along {Route} 95 and the Blackstone River stood vacant and crumbling. The resurgence in Massachusetts didn't just happen. It wasn't an accident. They had a strategy and a plan to create jobs and put cranes in the sky. They used job-training investments and incentives to create thousands of jobs in and around Boston.”

Why not study a success story?

Unlike many parochial powerbrokers of the past who were content to resist change, at the state’s peril, Raimondo recognizes that Rhode Island’s is part of a regional economy. Indeed, in many ways it is dependent on Massachusetts’s economy. Two-thirds of Rhode Island’s population is within a 20-minute drive to any Massachusetts border. (Incidentally, she made the trip at least twice last year by appearing on WGBH’s Greater Boston program, marketing her ideas and progress.)

Massachusetts’s Charlie Baker is the most popular governor in the country, with a 69 percent approval rating. He too is a moderate (a Rockefeller Republican), a technocrat, and also up for re-election this year. While Raimondo’s most recent approval rating stands at only 41 percent, that figure may be distorted and artificially low. Baker’s reforms have centered on the inner workings of government, largely lost on everyday residents. Raimondo’s reforms, meanwhile, have been about the very public machinations and expressions of government. Her controversial actions have directly affected, and been clear to, the entire electorate.

Today, the unemployment rate is 4.3 percent. Last March, The New York Times wrote, “Ms. Raimondo’s frenzy of economic and job development is striking because Rhode Island has long been in a slump. It was the last state to emerge from the recession that began in 2007. As recently as 2014, it bore the nation’s highest unemployment rate for seven months in a row.” At the same time, private-sector employment has reached its highest level ever.

Even with forward momentum, the governor may be more popular outside the state than within. Two years ago, Raimondo and then-Gov. Nikki Haley of South Carolina, a Republican who is now the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., were cited by Fortune Magazine as two female governors being among the world’s 50 greatest leaders. And last month, she was named as new vice chair of the Democratic Governors Association.

Big challenges, however, still loom large locally. The Pawtucket Red Sox, Boston’s minor-league affiliate, are threatening to leave the state. (Will the public finance a nine-figure stadium for a rich, privately owned team?) Nearly a third, or $3.1 billion, of the state budget is funded by the federal government. And opioids continue to consume lives.

But due to Raimondo’s centrist leadership -- despite the occasional progressive flourish (tuition-free community college) -- she has largely validated Kotkin’s hypothesis by focusing primarily on economic matters. Rhode Island might finally be poised for a 21st Century renaissance.

As the Slatersville bridge undergoes its third iteration in its third century, Rhode Island voters are reminded of this possibility in 2018 -- the Year of the Woman. Should Raimondo be re-elected and serve a full second four-year term, she would be just the third woman (all Democrats) in American history to do so (after Michigan’s Jennifer Granholm and Washington’s Christine Gregoire).

And with the Clintons out of the running, serious Democrats must consider her fortitude and record of accomplishment when they’re looking for vice-presidential timber for 2020.

James P. Freeman, a former banker, is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. His work has also appeared in The Providence Journal, newenglanddiary.com and nationalreview.com.

Charles Chieppo: In Mass. and elsewhere low returns imperil public pensions

In June, I wrote that public-sector pension plans were facing an existential crisis. Even though many states have adopted reforms, a sampling by the Center for State and Local Excellence of systems that cover 90 percent of the nation's state and local government pension-plan members found that in the last year the plans had on average of 74 percent of the money needed to fund their liabilities -- only a slight uptick from the previous year's figure of 73 percent.

That news was particularly troubling in light of a McKinsey Global Institute reportearlier this year suggesting that pension funds were likely to see lower investment returns going forward. Those McKinsey folks are looking awfully smart: A recent report from the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service found 20-year annualized returns for U.S. public pension systems at their lowest point in the nearly 15 years the service has tracked the statistic.

A look at public pension fund performance in Massachusetts suggests just how bad things might get and underlines the need for far more fundamental reforms if we are to pay for pensions without having to raise taxes or shift money away from core government functions. According to a recent Boston Business Journal report, in fiscal 2016 the state pension fund achieved a mere 1.14 percent return on its investments, just a fraction of the 7.5 percent assumed annual return on which the fund's financial projections are based.

And the state fund's performance looked pretty good compared to other Bay State public pension systems. Including the state fund, the 107 funds averaged returns of less than 1 percent. Twenty-two of the Massachusetts systems actually saw negative returns last year, and 20 have less than half of what they owe to current and future retirees. The pension system for Springfield, the state's third-largest city, is only 26 percent funded.

State officials have tried to put the pension funds on a path to solvency. In 2011, Massachusetts enacted reforms that included increasing the minimum retirement age and limiting the degree to which large salary increases just prior to retirement can boost pension payouts. But the impact of those reforms has been marginal.

Increasingly, it looks like sustainable pension programs will require reforms more likethose enacted earlier this year in Arizona, whose Public Safety Personnel Retirement System had in just over a decade gone from being fully funded to having less than half the assets needed to cover its liabilities. The fund's outlook is a lot better in the wake of a series of bold reforms. The maximum salary for purposes of pension calculations was reduced from $265,000 to $110,000. Current and future pension costs will be split evenly between employers and employees. And to reflect the shared risk, the number of labor representatives on the fund's board was increased.

Under the reformed system, new employees will choose between a defined-contribution plan and a hybrid that combines defined-contribution elements with those of traditional defined-benefit plans. While those new employees can't begin to collect retirement benefits until age 55, they can retire at any time. This important change makes pensions portable, so employees wanting to move on no longer have an incentive to stick around just so they can vest in the retirement plan.

The overhauled system will be so much less expensive that new employees will likely be required to make smaller pension contributions than current employees. In all, 30-year savings are expected to be more than a third of accrued liability.

Comprehensive reforms like those that Arizona has produced become all the more important in an era of paltry pension fund investment returns. While officials in other states may feel that they've already enacted politically difficult pension changes, it's become clearer than ever that the time for more sweeping action is upon us. And we know that nothing does more to add to the pain of necessary reforms than procrastination.

Charles Chieppo is a research fellow at the Ash Center of the Harvard Kennedy School and the principal of Chieppo Strategies, a public policy writing and advocacy firm. This piece first ran on governing.com. Charlie_Chieppo@hks.harvard.edu

More goodies for the elderly

"Untitled,'' by HELEN PAYNE, in the "Helen Payne: Becoming Four Women'' show at the New Art Center, Newtonville, Mass., Nov. 21-Dec. 20.

"Untitled,'' by HELEN PAYNE, in the "Helen Payne: Becoming Four Women'' show at the New Art Center, Newtonville, Mass., Nov. 21-Dec. 20.

Rhode Island politicians are falling over themselves to pander to the high-voting elderly by promising them that they'll pass a law to exempt the old folks (I'm one of them) from having to pay state income taxes on Social Security and pension money.

This means another goodie for the most affluent part of society and another transfer from those who earn their income to those who live on investments of various kinds, in which I'd include pensions and Social Security.

The lost tax revenue will have to be made up by younger, poorer people. If more of the latter bestirred themselves to vote, there would be a lot less of this growing inequity between the age cohorts. Serves them right.

This is what you get in a country where in the election last week, only 36.4 percent of eligible voters bothered to vote and the national outcome was decided by about 20 percent of eligible voters.

-- Robert Whitcomb