David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Elisabeth Rosenthal/ Emmarie Huetteman: He got tested for COVID-19; then came a flood of medical bills

By March 5, Andrew Cencini, a computer-science professor at Vermont’s Bennington College, had been having bouts of fever, malaise and a bit of difficulty breathing for a couple of weeks. Just before falling ill, he had traveled to New York City, helped with computers at a local prison and gone out on multiple calls as a volunteer firefighter.

So with COVID-19 cases rising across the country, he called his doctor for direction. He was advised to come to the doctor’s group practice, where staff took swabs for flu and other viruses as he sat in his truck. The results came back negative.

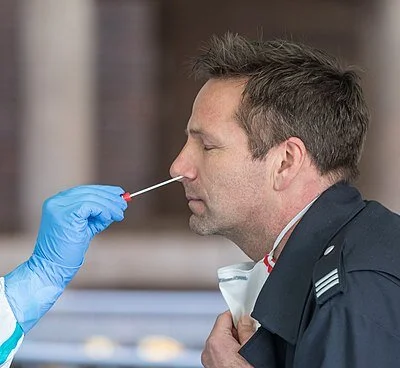

In an isolation room, the doctors put Andrew Cencini on an IV drip, did a chest X-ray and took the swabs.

— Photo courtesy of Andrew Cencini

By March 9, he reported to his doctor that he was feeling better but still had some cough and a low-grade fever. Within minutes, he got a call from the heads of a hospital emergency room and infectious-disease department where he lives in upstate New York: He should come right away to the ER for newly available coronavirus testing. Though they offered to send an ambulance, he felt fine and drove the hourlong trip.

In an isolation room, the doctors put him on an IV drip, did a chest X-ray and took the swabs.

Now back at work remotely, he faces a mounting array of bills. His patient responsibility, according to his insurer, is close to $2,000, and he fears there may be more bills to come.

“I was under the assumption that all that would be covered,” said Cencini, who makes $54,000 a year. “I could have chosen not to do all this, and put countless others at risk. But I was trying to do the right thing.”

The new $2 trillion coronavirus aid package allocates well over $100 billion to what Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York called “a Marshall Plan” for hospitals and medical needs.

But no one is doing much to similarly rescue patients from the related financial stress. And they desperately need protection from the kind of bills patients like Cencini are likely to incur in a system that freely charges for every bit of care it dispenses.

On March 18, President Trump signed a law intended to ensure that Americans could be tested for the coronavirus free, whether they have insurance or not. (He had also announced that health insurers have agreed to waive patient copayments for treatment of COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.) But their published policies vary widely and leave countless ways for patients to get stuck.

Although insurers had indeed agreed to cover the full cost of diagnostic coronavirus tests, that may well prove illusory: Cencini’s test was free, but his visit to the ER to get it was not.

As might be expected in a country where the price of a knee X-ray can vary by a factor of well over 10, labs so far are charging between about $51 (the Medicare reimbursement rate) and more than $100 for the test. How much will insurers cover?

Those testing laboratories want to be paid — and now. Last week, the American Clinical Laboratory Association, an industry group, complained that they were being overlooked in the coronavirus package.

“Collectively, these labs have completed over 234,000 tests to date, and nearly quadrupled our daily test capacity over the past week,” Julie Khani, president of the ACLA, said in a statement. “They are still waiting for reimbursement for tests performed. In many cases, labs are receiving specimens with incomplete or no insurance information, and are burdened with absorbing the cost.”

There are few provisions in the relief packages to ensure that patients will be protected from large medical bills related to testing, evaluation or treatment — especially since so much of it is taking place in a financial high-risk setting for patients: the emergency room.

In a study last year, about 1 in 6 visits to an emergency room or stays in a hospital had at least one out-of-network charge, increasing the risk of patients’ receiving surprise medical bills, many demanding payment from patients.

That is in large part because many in-network emergency rooms are staffed by doctors who work for private companies, which are not in the same networks. In a Texas study, more than 30 percent of ER physician services were out-of-network — and most of those services were delivered at in-network hospitals.

The doctor who saw Cencini works with Emergency Care Services of New York, which provides physicians on contract to hospitals and works with some but not all insurers. It is affiliated with TeamHealth, a medical staffing business owned by the private equity firm Blackstone that has come under fire for generating surprise bills.

Some senators had wanted to put a provision in legislation passed in response to the coronavirus to protect patients from surprise out-of-network billing — either a broad clause or one specifically related to coronavirus care. Lobbyists for hospitals, physician staffing firms and air ambulances apparently helped ensure it stayed out of the final version. They played what a person familiar with the negotiations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, called “the COVID card”: “How could you possibly ask us to deal with surprise billing when we’re trying to battle this pandemic?”

Even without an ER visit, there are perilous billing risks. Not all hospitals and labs are capable of performing the test. And what if my in-network doctor sends my coronavirus test to an out-of-network lab? Before the pandemic, the Kaiser Health News-NPR “Bill of the Month” project produced a feature about Alexa Kasdan, a New Yorker with a head cold, whose throat swab was sent to an out-of-network lab that billed more than $28,000 for testing.

Even patients who do not contract the coronavirus are at a higher risk of incurring a surprise medical bill during the current crisis, when an unrelated health emergency could land you in an unfamiliar, out-of-network hospital because your hospital is too full of COVID-19 patients.

The coronavirus bills passed so far — and those on the table — offer inadequate protection from a system primed to bill patients for all kinds of costs. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, passed last month, says the test and its related charges will be covered with no patient charge only to the extent that they are related to administering the test or evaluating whether a patient needs it.

That leaves hospital billers and coders wide berth. Cencini went to the ER to get a test, as he was instructed to do. When he called to protest his $1,622.52 bill for hospital charges (his insurer’s discounted rate from over $2,500 in the hospital’s billed charges), a patient representative confirmed that the ER visit and other services performed would be “eligible for cost-sharing” (in his case, all of it, since he had not met his deductible).

Last weekend he was notified that the physician charge from Emergency Care Services of New York was $1,166. Though “covered” by his insurance, he owes another $321 for that, bringing his out-of-pocket costs to nearly $2,000.

By the way, his test came back negative.

When he got off the phone with his insurer, his blood was “at the boiling point,” he told us. “My retirement account is tanking and I’m expected to pay for this?”

The coronavirus aid package provides a stimulus payment of $1,200 per person for most adults. Thanks to the billing proclivities of the American health care system, that will not fully offset Cencini’s medical bills.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: erosenthal@kff.org, @rosenthalhealth

Emmarie Huetteman: ehuetteman@kff.org, @emmarieDC

On the Bennington College campus on a dreary day