David Warsh: 'Depreciation,' 'development' and 'inflation'

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everyone knows that the cost of living has risen significantly in the past 75 years — recently, at rates not seen since the early ‘80s. To understand a little better why this has is happening, try this simple trick: Think of rising prices as a matter of the depreciation of the dollar against the prices of goods and services, instead of “inflation.” That won’t make the experience any less disorienting than calling it by the headline term, but it will give you a better sense of how and why the problem has arisen.

What’s the difference? With “inflation,” the answer is implied by the question. The explanation is always the same: the governors of the Federal Reserve Board have been cavalier with interest rates. Too much money is chasing too few goods. “Depreciation,” on the other hand, permits you to think about events taking place in the real world that forced the Fed’s hand – events that monetarists commonly describe as “ad hoc.”

Certainly a great deal of “ad hoc” change has occurred in the real world since 1950, when a candy bar cost a nickel and a haircut could be had for $1.25. Very little of the momentum behind that history would seem to have originated with the Fed, the stringent tightening of monetary policy in 1979-’82 being the major exception.

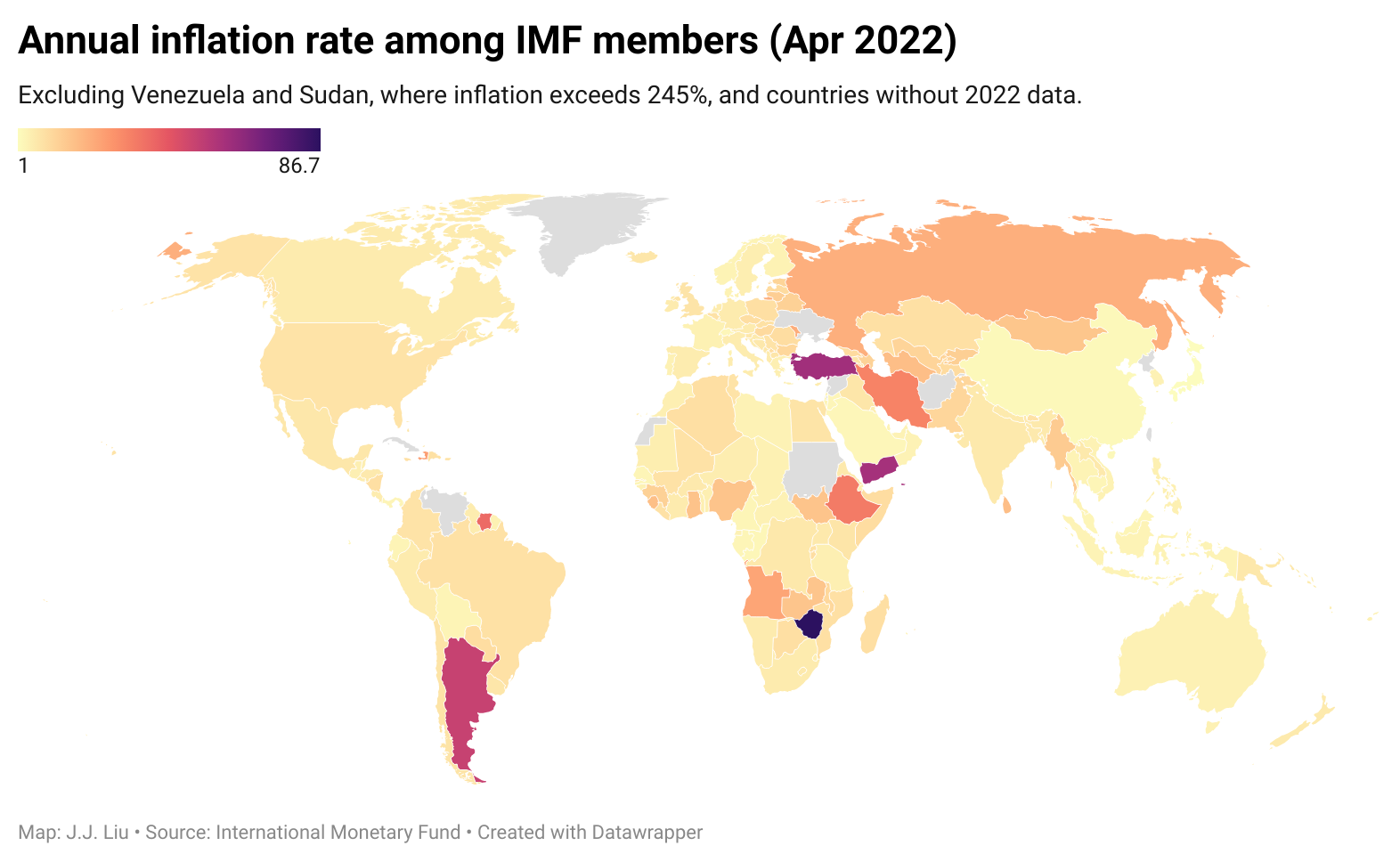

The current episode of rapidly rising prices is associated with the governmental response to COVID; accelerated with outbreak of all-out war in Ukraine; deglobalization of supply chains; food shortages and the threat of famine; policies designed to slow climate change, and energy disruptions now said to rival the crisis of the early and mid ‘70s.

True, in the course of regulating the nation’s system of money and banking, the Fed had to react to these various afflictions. Sometimes its governors may have overreacted. Sheer monetary incompetence can have a place in the story, too: Look no farther than the central bank of Sri Lanka for an example of that.

In the main, though, dollar depreciation occurs in response to real-world problems. Severe interest-rate policy can arrest expectations of runaway prices, as in the ‘80s. But dollar depreciation occurs in response to real forces. Never in millennia has it been reversed in a currency that endured. Repeating the mantra that “‘inflation’ is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” is just blowing hot air.

In The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics 1880-2000 (Cambridge, 2009), Thomas Stapleford, of the University of Notre Dame, describe how we came to employ sophisticated price indices to measure rising prices. The construction of economic statistics makes a fascinating story, but Stapleford spends only two paragraphs on why the cost of living changes, accepted at face-value explanations of particular episodes advanced by economists: W. Stanley Jevons, in the 19th Century, and Irving Fisher, in the 20th. In each case, the economists asserted, when “the supply of money increased, its value would fall, leading to higher prices.” Hence the “inflation” of prices by an excess of money.

But what if it works the other way around? What if the “cost-push” argument is more often correct? What if the quantity of money increases because prices are rising? Every central banker knows it is not simply one or the other; it is both. But with “inflation,” you only see one side of the story – in most instances, the less important side.

We don’t know more because there exists no conceptual scheme of sufficient generality to organize all those various “ad hoc” explanations of rising prices under one heading. Whatever intuitive appeal has existed in the term “complexity,’’ “complexity” was already well on its way to becoming a magic word, an incantation, quite devoid of meaning.

The second mistake I made was failing to notice that economists already possessed a serviceable term of their own to describe this dimension of modern life. They called it “economic development,” words as familiar and easy to use as they were lacking in precision. To give it meaning to development, as opposed to “growth,” which is a matter of inputs and output, requires only linking back to one of the most fundamental categories in all of economic theory: the division of labor.

Easier said than done! Although the role of specialization in producing material well-being is clearly spelled out in the first three chapters of An in Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith quickly moves on to the analysis of a competitive system, and this is the tradition, taken up by David Ricardo and T.R. Malthus, that has dominated economics down to the present day. I was slow to figure this out.

There! After fifty years of writing about these topics, often clumsily, my two key mistakes are acknowledged, and I have set out here all I have learned: “depreciation” and “development” (understood as the extent of the division of labor) are better language than “inflation,” not to mention (here I blush) “complexity” and “conflation” in 1984.

For a glimpse of how things might yet be different, and probably will be before long, see “One Analogy Can Hide Another: Physics and Biology in Alchian’s ‘Economic Natural Selection’”, by Clément Levallois, which ultimately appeared in 2009 in History of Political Economy. (JSTOR access required). Or tune in to Nathan Nunn, now back at the University of British Columbia. But the biological analogy at the heart of the re-launch of evolutionary economics in the years after World Wat II is too wonky for this column.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Seven Hills Park at Davis Square, Somerville. The towers in the park each represent one of the city's original hills.