David Warsh: America’s fracturing ‘politics of purity’ since the ‘70s

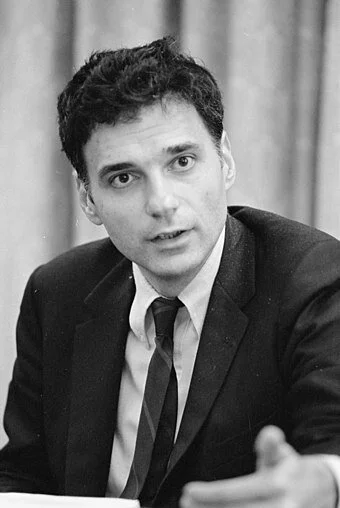

Ralph Nader in 1975, in his heyday

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Like a lot of people, I am interested in what has been happening in the world, the U.S. in particular, since the end of World War II. I am especially intrigued by goings on in university economics, but I take a broad view of the subject. I grew up in the Fifties, and the single most persuasive account I’ve found of the underlying nature of changing times since 1945 has been a series of five books by historian Daniel Rodgers, of Princeton University. In Age of Fracture (Belknap, Harvard, 2011), Rodgers described very well my experience of the increasingly thinner life of things.

Across the multiple fronts of ideational battle, from the speeches of presidents to books of social and cultural theory, conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions, and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind, the last quarter of the century was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.

But I’m always interested in a new narrative. One such is Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (Norton, 2021), by historian Paul Sabin, of Yale University. Sabin employs the career of Ralph Nader, the arc of which extends from Harvard Law School and auto-safety crusader in Sixties to his Green Party candidacy in the U.S. presidential election of 2000, as a metaphor for a variety of other liberal activists who mounted assaults of their own on centers of government power in the second half of the 20th Century.

The harmonious post-war partnership of business, labor and government proclaimed in the Fifties by economist John Kenneth Galbraith and New Dealer James Landis, symbolized by the success of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s government-sponsored electrification of the rural South, was not built to last. But how did government go from being the solution to America’s problems to being the cause of them? It was more complicated than Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, Sabin shows.

Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961), Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962) and Nader (Unsafe at Any Speed. 1965), were exemplars of a new breed of critics of capture industrial manipulation and capture of government function, Sabin writes. Jacobs attacked large-scale city planning and urban renewal. Carson exposed widespread abuses by the commercial pesticide industry. Nader criticized automotive design. These were only the first and most visible cracks in the old alliance of industries, labor unions and federal administrative agencies. Public-interest law firms began springing up, loosely modeled on civil-rights organizations. The National Resources Defense Council; the Conservation Law Foundation; the Center for Law and Social Policy and many other start-ups soon found their way into federal courts. Nader tackled the leadership of the United Mineworkers Union, leading then-UMW President Tony Boyle to order the murder of reform candidate Tony Yablonski, his wife, and daughter, on New Year’s Eve, 1969.

In Age of Fracture, Rodgers wrote that “The first break in the formula that joined freedom and obligation all but inseparably together began with Jimmy Carter.” Carter’s outside-Washington experience as a peanut farmer and Georgia governor, as well as his immersion in low-church Protestant evangelical culture led him to shun presidential authority. “Government cannot solve our problems, it can’t set our goals, it cannot define our vision,” he said in 1978.

Sabin takes a similar view but offers a different reason for the rupture. Caught in between the idealistic aspirations of outside critics inspired by Nader and the practical demands of governing by consensus, Carter struggled to maintain the traditional balance but failed to placate his critics. “Disillusionment came easily and quickly to Ralph Nader,” Sabin writes. “I expect to be consulted, and I was told that I would be,” Nader complained almost immediately. Reform-minded critics attacked Carter from nearly every direction. A fierce primary challenge by Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D.-Mass.) failed in 1980. The stage was set for Ronald Reagan.

Sabin recalls the battles of the 1970s with grim determination to show the folly of politics of purity. Nader made his first run for the presidency as leader of the Green Party in 1996, challenging Bill Clinton and Bob Dole. He was in his sixties; his efforts were half-hearted. In his second campaign, in 2000, he campaigned vigorously enough to tip the election to George W. Bush. Even then it wasn’t Nader’s last hurrah. He ran again, in 2004, as candidate of the Reform Party; and a fourth time, as an independent, in 2008. At 87, he is today conspicuously absent from the scene.

The public-interest movement initiated by urbanist Jane Jacobs, scientist Rachel Carson and Ralph Nader was effective in its early stages, Sabin concludes. The nation’s air and water are cleaner; its highways and workplaces safer; its cities more open to possibility. But Sabin is surely right that all too often, go-for-broke activism served mainly to undermine confidence in the efficacy of administrative government action among significant segments to the public.

The critique of federal regulation was clearly not the whole story, any more than was The Great Persuasion, undertaken in 1948 by the Mont Pelerin Society, pitched unsuccessfully in 1964 by presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and translated into slogans in 1980 by Milton and Rose Friedman. Nor is the thoroughly disappointing 20-year aftermath to 9/11, another day when the world seemed to many to “break apart,” as historian Dan Rodgers put it in an epilogue to Age of Fracture.

What might put it back together? Accelerating climate change, perhaps. But that’s another story.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.