I was invited recently to an online seminar with this title: “Preparing for the Great Generational Wealth Transfer.”

As a financial professional -- with experience as a private wealth advisor -- I found the subject matter to be particularly intriguing. After all, as a marketer and thought leader today, I look at emerging trends -- behavioral, demographic, and technological, among others -- as a means by which to foster and sustain long-term relationships with clients and prospective clients, alike. All of the looming changes articulated during the webinar (and others I have seen on the horizon) will certainly provide challenges and opportunities in the financial advice business for both the consumer and advisor. But the changes herewith will be seismic.

The webinar presentation was inspired by research conducted by Boston-based Cerulli & Associates, a firm which delivers financial market intelligence to the industry. Cerulli projects that, in the greatest intergenerational reallocation of wealth ever, $70 trillion will be transferred between generations (Silent Gen and Baby Boomers to Gen X and Millennials) by the year 2042. That prediction alone is worthy of our collective attention.

But will that happen? I have my doubts.

Surely, retirement for today’s younger generations will be vastly different from retirement experienced by today’s older generations. But the dollar volume estimated to be passed down seems to me to be fantastically overcooked. Expect the expected. Let me give you my unified field theory.

First, it is important to look at the emerging demographic patterns for a sense of perspective.

Strength in numbers

While the Silent Gen (1928-1945) still plays a role in this “great transfer,” the focus here remains on Baby Boomers. Boomers were born between 1946 and 1964 -- at one point seventy-six million strong. The first Boomer reached the age of 65 -- commonly called “retirement age” -- in early 2011. Today, 10,000 Boomers are turning 65 every single day. Beginning in 2024, however, that figure accelerates to 12,000 per day, in what is being called “Peak 65.” The pace will decline markedly as the last Boomer turns 65 in December 2029. Even more incredibly, sometime during the next decade, one in five Americans will be over the age of 65. That has never happened before.

Gen X members (sometimes referred to as the “MTV Generation”) were born between 1965 and 1980. Today they are between the ages of 41 and 56 and are in the peak earnings years of their careers; the oldest are just starting to contemplate retirement. According to 2019 U.S. census data, they are 65.2 million strong. The oldest Gen Xer has more in common with the youngest Boomer while the youngest Gen Xer has more in common with the oldest Millennial. Arguably, Gen X is a shadow generation given that it is smaller than the Boomer generation preceding it and the Millennial generation following it. And notably, Millennials have eclipsed all other generations for sheer size. So, the attention paid to them is warranted.

Millennials were born between 1981 and 1996. In 2016, Millennials became the largest generation in the U.S. labor force. With 87 million members, Millennials also now represent the largest demographic group in America, surpassing the Boomer generation. In fact, Millennials are the largest adult cohort in the world. Right before their eyes, Boomers are ceasing to be the most influential generation. More than half of Americans are now Millennials or younger, reports brookings.edu

Nonetheless, as the greying of America continues, the median age is now just over 38. Fifty years ago, it was closer to 28 and has been rising ever since.

Adrian Johnstone, president, and co-founder of Practifi, a business management platform for financial advice, was the featured webinar speaker. He delivered examples of the stark contrasts between the generations in how they view the future and view retirement. As you can imagine, there are big cultural differences between these generations. It literally is a generation gap

Understandably, then, Boomers and Millennials have different objectives. At least as understood right now.

Demographics is destiny

Boomers more or less created the financial retirement business. As I like to say it was “of Boomers, by Boomers, and for Boomers.” Not too long ago, a Boomer was likely to measure success in a retirement portfolio by “benchmarking.” For example, this meant comparing the performance of an individual investment portfolio to something like the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, a broad market index that measures performance. It was an accomplishment if you beat a given index in a given year. But defining success has evolved over time.

Smart people began saying this about benchmarking: “So what?”

Retirement planning was more than just investment performance. Industry leaders started looking at planning in a much more holistic way. Soon, business models would build around a “process” to drive success based on “goal setting.” The thinking was that you had a greater probability of achieving your goals if you followed a process. That concept changed the mindset from the short-term to long-term. Indeed, retirement planning was a long-term journey. The rationale was that retirees should consider whether or not they were achieving their goals as the best way to effectively measure progress in retirement. “Goals” was a much broader concept than “benchmarks,” yet it was much more focused, too -- buying a second home, taking annual vacations, investing in long-term care, setting up gifting, losing weight, etc. Markets go up and go down. But if you could achieve your overall goals despite inevitable market turbulence that was the new paradigm for defining success in retirement.

My sense, however, is that this current model is beginning to change as well. While goals will always be part of retirement planning, I question if setting lofty, long-term goals (even if practical) may prove to be elusive for many retirees going forward. My reasoning is straightforward.

The youngest Boomer and oldest Gen X have had to weather three once-in-a-lifetime events that affected retirement planning and saving in just the last twenty years. (Dotcom in 2000, Great Recession in 2009, COVID-19 in 2020). Combine these events with future funding issues for Social Security, Medicare, and Long-Term Care needs, it paints a less certain financial picture. Throw in the fact that this demographic carve-out is more in debt than older retirees and the relative financial future seems even less assured for them. Goals, then, seem illusory.

Given these realities, I believe that financial planning will once again morph into a new realm. Discussions will center more on “lifestyle” (or standard of living) and less on goal setting. Maintaining -- if not improving -- one’s lifestyles is a more focused conversation than goals; it’s much more tangible than goals, too. Telling clients they will not be able to maintain a given lifestyle is much more powerful than telling them they can not reach a goal.

So, in the span of fewer than forty years, you can see the progression of retirement planning models in how performance is often measured. It began with comparing benchmarks to setting goals and will likely shift even more to living desired lifestyles. Enter Millennials…

Now please fasten your seatbelts before departure

The Practifi webinar suggested even more pronounced changes when Millennials begin serious retirement consideration. According to Johnstone, this generation will be mostly concerned about values -- such as social responsibility and the impact of their decisions on the larger society. In other words, for them, retirement planning must center around their values, with everything else, including, presumably, performance, of less or equal import.

That is a radical shift in priorities.

Additionally, financial advisors should anticipate other changes in how future generations approach retirement. They are just as compelling.

The retirement landscape will probably look unrecognizable after the last Boomer retires in 2029, presenting new complexities for all interested parties.

Surely, there will be a transfer of wealth (more about which anon) and advisors will need to be aligned with the interests of the next generation (values more than goals). Likewise, “NextGen” retirees will have crypto currencies and ESG investments (environment, social, and governance) as staples in their portfolios. They will also be more inclined to make micro loans, a newfangled investment alternative. Fee structures will undoubtedly be altered. Marketing will be impacted by implementing AR (augmented reality) into social media and other platforms. The regulatory apparatus will also look hugely different. And AI (artificial intelligence) software tools will complement human advisors. Finally, future retirees will be more financially literate, more skeptical, and more engaged (via technology) about, well, everything.

Advisors in the future doubtless must change from a Boomer-centric retirement model to a Millennial-centric retirement model not only to accommodate the next retirement class but to prepare for the predicted wealth transfer. For Johnstone, he sees a sea-change from the client point of view, too. He believes that Boomers are “delegators” of their retirement (to advisors). Whereas Millennials will be “validators” of their retirement (from advisors).

Show me the money!

Notwithstanding the extraordinary metamorphosis about to play out in a couple of years in terms of demographics and service delivery models, the real question is about assets. This past June, The Wall Street Journal reported that the great transfer has already begun. It cited Federal Reserve data indicating that Americans over the age of 70 had already accumulated “a net worth of nearly $35 trillion.” That amounts to 27 percent of all U.S. wealth, up from 20 percent three decades ago.

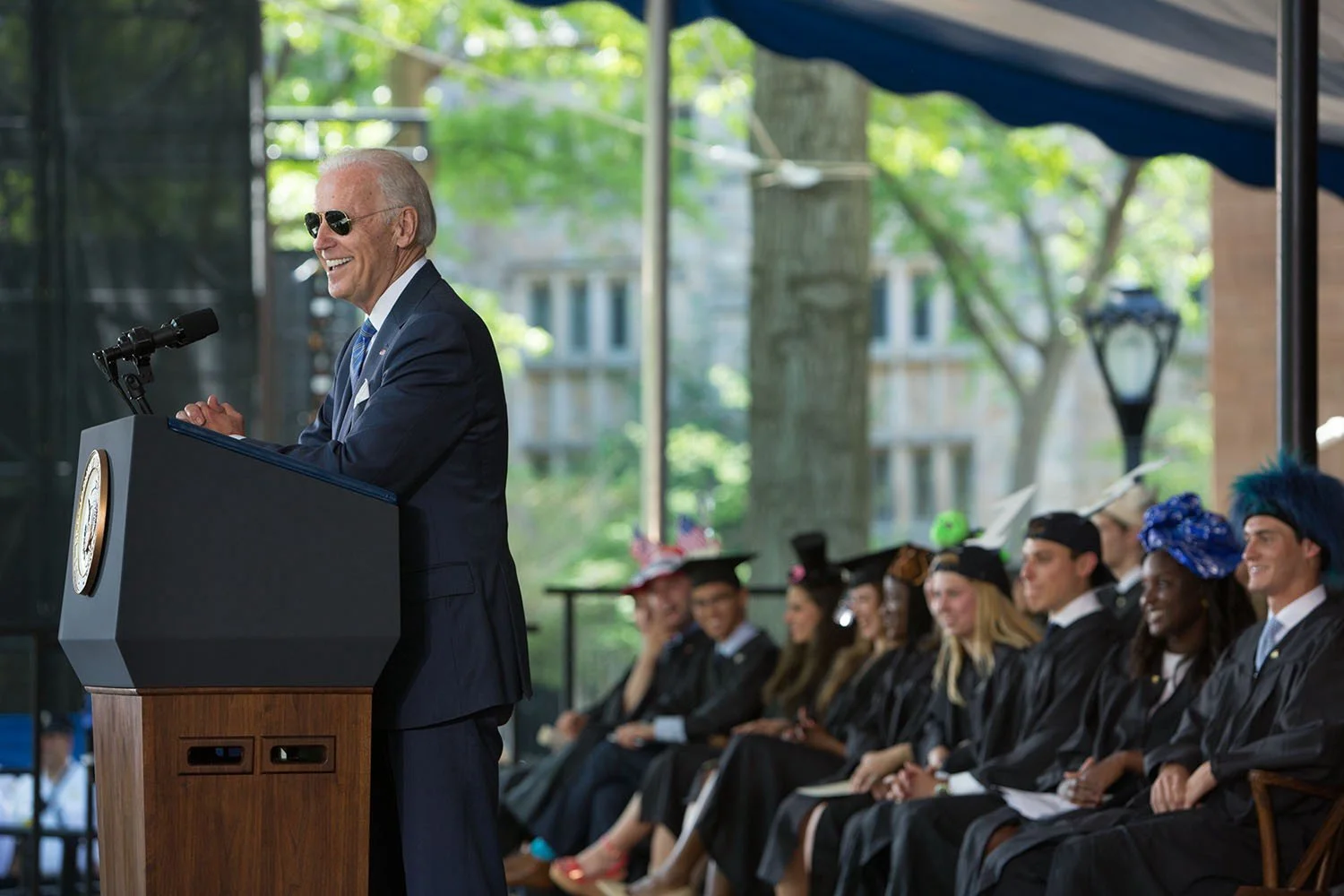

Still, I am not entirely convinced that $70 trillion in assets will ultimately be transferred to heirs and charities, as predicted. That stockpile of money seems high. To better understand that dollar amount, it would mean the transference of roughly $3.3 trillion every year for the next twenty years. Put another way, the total would be the combination of President Biden’s $1.9 trillion Build Back Better Act and $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Acts, annually, up to 2042.

Labyrinthine financial trends might well offset the amount substantially.

The real question should be: Will known (and unknown) massive unfunded liabilities eventually absorb much of the $70 trillion because we have simply failed to live within our means today? We have shifted many of today’s financial burdens on younger generations and even generations not yet born. The arithmetic just doesn’t square.

Conceivably, much of these assets would be liquidated -- and hence evaporated -- prior to any transferring or gifting because of future costs. Consider the following four factors: poor savings, rising healthcare costs, Social Security funding concerns, and high personal (not to mention high institutional and governmental) debt loads. It is the liabilities side of the balance sheet that concerns me. Not the assets side.

Something has gotta give

POOR SAVINGS

Despite a staggering amount of cash flooding into the American economy as part of COVID-19 relief (read about the $5.2 trillion in pandemic fiscal stimulus), not to mention an absurdly accommodative monetary policy, America still has a savings problem. (Remember food lines queuing up just a couple of weeks after the first lockdowns in early 2020? We were told people did not have money saved for such “emergencies.”) I don’t subscribe to the idea -- as perpetuated by economists, usually the last group of people “in-the-know” -- that Americans have significantly improved their savings rates. Saving is a behavioral attribute. Have behaviors really changed for the long term? Any built up savings is likely a temporary phenomenon. I write that because much of the chatter we hear from financial commentators centers on all this “pent up demand” stemming from the pandemic. Such demand, we are told, is exacerbating the supply-chain problems. A probable outcome will be all the extra cash will be spent.

Earlier this year the Insured Retirement Institute released the results of a survey conducted on workers between the ages of 40 and 73. Its findings were unsurprising but consistent with many similar studies on worker preparedness for retirement. Two key takeaways were as follows: savings behavior needs to improve, and retirement income expectations are unrealistic. The survey found that 51 percent of respondents had less than $50,000 saved for retirement. Furthermore, the report concluded that “Among savers, savings rates are not nearly high enough for even the youngest respondents to grow their nest eggs to a level sufficient for meeting their income and budget expectations.” The survey was conducted after much of the stimulus was already distributed into personal and small business accounts.

And, perhaps most alarming, the institute wrote that, across several measures of retirement preparedness, “most [respondents] fear they will not have enough income, will not be prepared to transition into retirement, will not have enough money for medical expenses or long-term care should the need arise, and may not be able to live independently for the entirety of their retirement.” A large number of Americans are not putting enough aside to catch up.

Americans’ use of retirement plans has changed dramatically over the last several decades, too. In the past, good-ole-fashion “defined benefit plans” (think pensions) were the norm. They were a stable retirement income source for millions of retirees. But many pension plans -- especially in the public sector -- are grossly underfunded today. The 401(k) was born in 1978 and known as a “defined contribution plan.” Such contribution plans were devised to supplement benefit plans but over time they ended up supplanting those benefit plans. And at their root, 401(k) plans were really DIY plans -- or “do-it-yourself” plans. The result was that the American worker became the principal source of his or her retirement savings, not a corporation or municipality. And the data confirm that Americans are not contributing enough to these plans. Therefore, it is hard to see where additional savings are built into future retirement portfolios -- unless people rely mostly upon enormous equity gains in real estate holdings. Besides, government policy discourages saving (with artificially and historically low interest rates) and encourages speculating (with greater yields in riskier market investments). This is even more outrageous considering higher inflation has returned with gusto.

As 2021 ends, I would imagine that future studies examining the impacts of all this stimulus will confirm that the notion of any substantive increase in savings and savings rates is a grand chimera.

RISING HEALTHCARE COSTS

Nearly ten years ago, in a 2012 speech at the U.S. Naval War College, conservative columnist George Will, then 69, showed those in the audience his Medicare Card. He had also previously shown it to his doctor. To which his doctor said, “That’s wonderful, George, we’ll send your bills to your children.”

Both “Romneycare” (in Massachusetts) and “Obamacare” (at the national level) largely fulfilled their aims of insuring many more of its residents and citizens, respectively, for healthcare. However, neither program did anything to bend the cost curve. In Massachusetts, for instance, healthcare costs now represent 36 percent of total state spending. It was 31.5 percent just three years ago. For fiscal 2008, the figure was approximately 30 percent.

In case you missed it, healthcare costs have been rising and will continue rising, yet few want to pay for spiraling costs. According to healthsystemtracker.org, health spending in America totaled $74.1 billion in 1970. Three decades later, by 2000, health expenditures reached about $1.4 trillion. Put another way, “In 1970, 6.9 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the U.S. was spent toward total health spending (both through public and private funds). By 2019, the amount spent on healthcare has increased to 17.7 percent of the GDP.” It is expected that the number will reach 18 percent soon.

Healthcare costs in this country continue to accelerate because of the intersection of demographics (Boomers retiring in large numbers) and better medicine (diagnostic, therapeutic, pharmacologic). Today, we are consuming $3.8 trillion or $11,582 per person, annually, on healthcare. This is nearly three times what was spent only twenty years ago. And with more Boomers consuming even more healthcare in the future, our healthcare system will strain with greater costs. Spending will sharply hasten.

Data in a 2021 extract provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reveal that American households paid, on average in 2018, 18.5 percent of their income towards healthcare costs. In addition, “According to Medicare beneficiaries’ data, in 2017, the average total health expenditures in their last year of life was $66,176.”

Medicare currently covers nearly 64 million Americans today. And funding for the program accounted for more than 4 percent of the U.S. GDP in 2020, reports medicareresources.org. Total Medicare spending stood at $917 billion last year, and it is expected to grow to $1.78 trillion in 2031, or two years after the last Boomer retires.

Medicare, established in 1965 as part of The Great Society, has critical funding challenges just like Social Security -- but they are more immediate. It is estimated that the Medicare Trust Fund will be exhausted in 2024 unless Congress acts to implement new reforms. Barring no changes, the Congressional Budget Office projects that following 2024 exhaustion, Medicare will only have sufficient tax receipts to be able to pay 83 cents for every dollar covered. There are three practical solutions to avoid insolvency, concluded forbes.com this past March: “Increase revenues flowing into the trust fund by at least $700 billion to extend solvency to 2036 (experts typically focus on 10-year time horizons); cut spending on Medicare beneficiaries or increase their monthly premiums; or figure out a combination of these two methods.”

All of these challenges were known as far back as twenty years ago. In 2002, Health Services Research issued a study named “The 2030 Problem: Caring for aging Baby Boomers.” Few have paid heed to the warnings that it issued back then. “To meet the long-term care needs of Baby Boomers,” its authors wrote, “social and public policy changes must begin soon.” In 2021, it is obvious that these changes never occurred.\

SOCIAL SECURITY FUNDING

In many respects, healthcare cost concerns are a bigger worry than Social Security because the latter is more manageable and knowable: We have decades of economic data and demographic data to ascertain future costs. We know healthcare costs will rise but it is such a wildcard that it is difficult to enumerate actuarial costs. With Social Security the math is right in front of us, and it is largely predictable. But reforms are needed.

According to the Social Security Administration, the ratio of covered workers to beneficiaries was 159 to 1 in 1940; that figure shrank to 2.8 to 1 in 2013. It is estimated to be 2.7 today. However, when the last Boomers reach age 75, the trustees of the program project that “the ratio will fall to 2.2 to 1 in 2039.”

And unless, in this politically charged environment, changes are made to how Social Security is funded, it will not support paying out 100 percent of benefits beginning in 2034. Barring no change, payroll taxes will only then be able to distribute approximately 75 percent of promised payments. Like Medicare, it would seem that a combination of higher taxes and lower payouts would be the most likely outcome. But that is impossible to predict.

Estimates vary on how much retirees rely entirely on Social Security as a source of income in later years.

The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) in January 2020 reported that, “A plurality of older Americans, 40.2 percent, only receive income from Social Security in retirement.” That analysis was called into question by Andrew G. Biggs, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Biggs has written extensively on retirement matters. Using different data points collected by other governmental agencies, he found there is not a consensus on the NIRS thesis. Instead, there is evidence that between 12 percent and 20 percent of older Americans rely solely on Social Security for support. Even if those figures are closer to reality, it is a fact that millions of retirees depend on Social Security as a significant source of income. So, this question remains pertinent: What would a potential 25 percent reduction in Social Security benefits do to seniors?

Arguably, in order to finance the current level of Medicare and Social Security benefits for future retirees (will there ever be higher levels of spend?), higher payroll taxes would seemingly be the quickest fix. And it is not too farfetched to reason that inheritance taxes would also rise to address these systemic problems, too. These measures would certainly eat into the great transfer of $70 trillion.

IN DEBT WE TRUST

My favorite website may be debt.org.

The site is really an advocacy platform that wishes to help people who are in debt, but I find it as a reliable financial resource. Its “Demographics of Debt” page is a helpful amalgam of disparate data points that exposes a crisis like an asteroid approaching earth. Recent updates to the page have included debt tabulations made during the pandemic.

American household debt hit a record $14.6 trillion in the spring of 2021, according to the Federal Reserve. (Housing likely accounts for 71 percent of that total.) Furthermore, last year, rather disturbingly, “The total U.S. consumer debt balance grew $800 billion, according to Experian. That was an increase of 6 percent over 2019, the highest annual growth jump in over a decade.” Borrowers have been the beneficiaries of historically low interest rates for over a decade now. This has, in my opinion, been an inducement to borrow more without consequences. But with higher inflation now center stage for an economy that has experienced benign inflation for decades, it would seem that the Federal Reserve would be poised to raise interest rates sooner than later. Such action would make it more expensive to borrow and would obviously make servicing debt more expensive, especially for adjustable-rate debt instruments. (Interestingly, Adjustable Rate Mortgages make up just 3.4 percent of all mortgage applications today; as of 2020, approximately 44 percent of U.S. consumers have a mortgage; in Massachusetts the average individual mortgage balance is $261,345, as of 2020.)

I am keenly interested in the breakdown of debts among the demographic groups. The anticipated great transfer of wealth would imply that older generations (Silent Gen and Boomers) would be relatively unencumbered by debts to allow them to freely pass along assets to heirs (Gen X and Millennials) and charities. On the contrary, the data suggest that picture less clear.

Of these four demographic groups, the Silent Gen has the lowest amount of average debt per member ($41,281), while Millennials have the third lowest ($87,448). What is somewhat surprising is that Boomers place second, having an average of $97,290 of debt per member. Meanwhile, Gen X can claim the largest debt burdens for this comparison with an average of $140,643 per Xer. Academically, this all makes sense as Gen X is still paying off the bulk of its mortgage obligations and the same may be said for the youngest Boomer as well.

It seems to me, that despite the fact that Boomers are no longer the largest demographic cluster, they will largely determine whether or not the great transfer of assets actually happens.

I do not see how the bulk of $70 trillion ever gets delivered to younger generations. I believe that future costs (for healthcare, Medicare, and Social Security) will emphatically eat up much of those assets. Boomers will inevitably be more “takers” than “makers” of the great transfer. Finally, I believe that servicing existing individual debt loads will be as much of a factor in the future as it is today. We also should be mindful of the exorbitant levels of debt at the government and institutional levels that will also need adequate funding. Time was when we borrowed for the future. We now borrow from the future. There is no escape from The Great Debt.

Years ago, I did a short stint as a substitute teacher. I would argue that the elementary classroom is a more challenging environment than the Wall Street boardroom, and higher learning more perspicacious than higher returns. One fine day I was teaching first graders. There was some free time before dismissal, so I simply asked them to draw anything they wanted -- a token for the ride home after school. It was a fun exercise. As I was circulating around the children, watching future Picassos toil away, I came across a young girl named Sally. I couldn’t quite figure out what she was sketching. So, I asked, “Sally, what is that?” She paused, and with steely determination, she said, “I am drawing a picture of God.” I made the mistake of responding, “Well, Sally that’s quite something because no one knows what God looks like.” To which she retorted, with breezy confidence: “They will in a minute.”

With regard to the great wealth transfer and attendant ramifications, we will see in a New York minute.

James P. Freeman is the director of marketing at Kelly Financial Services, LLC, based in in Greater Boston. For much of his professional career in financial services he was an officer in the bond administration departments of a number of banks and trust companies. This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase any interest in any investment vehicles managed by Kelly Financial Services, LLC, its subsidiaries, and affiliates. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not accept any responsibility or liability arising from the use of this communication. No representation is being made that the information presented is accurate, current, or complete, and such information is at all times subject to change without notice. The opinions expressed in this content and or any attachments are those of the author and not necessarily those of Kelly Financial Services, LLC. Kelly Financial Services, LLC does not provide legal, accounting or tax advice and each person should seek independent legal, accounting and tax advice regarding the matters discussed in this article.