From Kaiser Health News

PORTLAND, Maine

Fran Seeley, 81, doesn’t see herself as living on the edge of a financial crisis. But she’s uncomfortably close.

Each month, Seeley, a retired teacher, gets $925 from Social Security and a $287 disbursement from an individual retirement account. To make ends meet, she’s taken out a reverse mortgage on her home here that yields $400 monthly.

So far, Seeley has been able to live on this income — about $19,300 a year — by carefully monitoring her spending and drawing on limited savings. But should her excellent health worsen or she need assistance at home, Seeley doesn’t know how she’d pay for those expenses.

More than half of older women living alone — 54% — are in a similarly precarious financial situation: either poor according to federal poverty standards or with incomes too low to pay for essential expenses. For single men, the share is lower but still surprising — 45%.

That’s according to a valuable but little-known measure of the cost of living for older adults: the Elder Index, developed by researchers at the Gerontology Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

A new coalition, the Equity in Aging Collaborative, is planning to use the index to influence policies that affect older adults, such as property tax relief and expanded eligibility for programs that assist with medical expenses. Twenty-five prominent aging organizations are members of the collaborative.

The goal is to fuel a robust dialogue about “the true cost of aging in America,” which remains unappreciated, said Ramsey Alwin, president and chief executive of the National Council on Aging, an organizer of the coalition.

Nationally, and for every state and county in the U.S., the Elder Index uses various public databases to calculate the cost of health care, housing, food, transportation and miscellaneous expenses for seniors. It represents a bare-bones budget, adjusted for whether older adults live alone or as part of a couple; whether they’re in poor, good or excellent health; and whether they rent or own homes, with or without a mortgage.

Results from the analyses are eye-opening. In 2020, according to data supplied by Jan Mutchler, director of the Gerontology Institute, the index shows that nearly 5 million older women living alone, 2 million older men living alone, and more than 2 million older couples had incomes that made them economically insecure.

And those estimates were before inflation soared to more than 9% — a 40-year high — and older adults continued to lose jobs during the second and third years of the pandemic. “With those stressors layered on, even more people are struggling,” Mutchler said.

Nationally and in every state, the minimum cost of living for older adults calculated by the Elder Index far exceeds federal poverty thresholds, which are used to calculate official poverty statistics. (Federal poverty thresholds used by the Elder Index differ slightly from federal poverty guidelines. Data for each state can be found here.)

One national example: The Elder Index estimates that a single older adult in good health paying rent needed $27,096, on average, for basic expenses in 2021 — $14,100 more than the federal poverty threshold of $12,996. For couples, the gap between the index’s calculation of necessities and the poverty threshold was even greater.

Yet eligibility for Medicaid, food stamps, housing assistance and other safety-net programs that help older adults is based on federal poverty standards, which don’t account for geographic variations in the cost of living or medical expenses incurred by older adults, among other factors. (This isn’t an issue for older adults alone; the poverty measures have been widely critiqued across age groups.)

“The poverty rate just doesn’t cut it as a realistic look at the struggles older adults are having,” said William Arnone, chief executive officer of the National Academy of Social Insurance, one of the new coalition’s members. “The Elder Index is a reality check.”

In April, University of Massachusetts researchers showed that Social Security benefits cover only a fraction of what older adults need for basic living expenses: 68% for a senior in good health who lives alone and pays rent and 81% for an older couple in the same situation.

“There’s a myth that Social Security and Medicare miraculously take care of all of people’s needs in older age,” said Alwin, of the National Council on Aging. “The reality is they don’t, and far too many people are one crisis away from economic insecurity.”

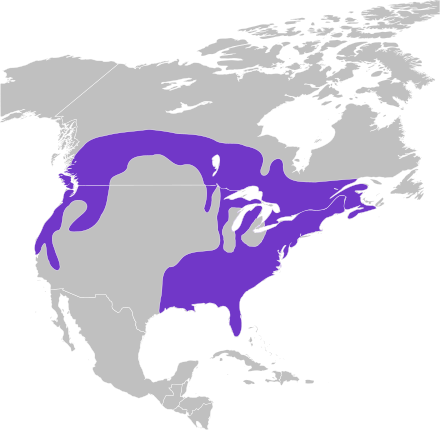

Organizations across the country have been using the Elder Index to convince policymakers that older adults need more assistance. In New Jersey, where 54% of seniors are economically insecure according to the index, advocates used the data to protect property-tax relief programs for older adults during the pandemic. In New York, where nearly 60% of seniors are economically insecure, advocates persuaded the legislature to raise the Medicaid income eligibility threshold.

In San Diego, where as many as 40% of seniors are economically insecure, Serving Seniors, a nonprofit agency, persuaded county officials to use pandemic-related stimulus payments to expand senior nutrition programs. As a result, the agency has been able to double production of home-delivered meals, to more than 1.5 million annually.

Officials are often wary of the financial impact of expanding programs, said Paul Downey, president and CEO of Serving Seniors. But, he said, “we should be using a reliable measure of economic security and at least know how well the programs we’re offering are doing.” By law, California’s Area Agencies on Aging use the Elder Index in their planning process.

Maine is No. 5 on the list of states ranked by the share of seniors living below the Elder Index, 56%. For someone in Fran Seeley’s situation (an older adult who is in excellent health, lives alone, owns a house, and doesn’t pay a monthly mortgage), the index suggests $22,560 a year is necessary — $3,200 more than Seeley’s annual income and $9,500 above the federal poverty threshold.

Fran Seeley’s income — from Social Security, a retirement account, and a reverse mortgage — comes to about $19,300 a year. With inflation increasing, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can,” Seeley says.

A look at Seeley’s budget reveals how quickly necessary expenses accumulate: $2,041 annually for Medicare Part B (this is deducted from her Social Security check), $4,156 for property and stormwater taxes, $390 for home insurance, $320 for furnace cleaning, $1,440 for heat, $125 for water, $500 for gas and electricity, $300 for property maintenance, $1,260 for phone and Internet, $150 for car registration, $640 for car insurance, $840 for gasoline at current prices, $300 for car maintenance, and $4,800 for food.

The total: $17,262. And that doesn’t include the cost of medications, clothing, toiletries, any kind of entertainment, or other incidentals.

Seeley’s great luxury is caring for four cats, which she describes as “the light of my life.” Their annual wellness checks cost about $400 a year, while their food costs about $1,080.

With inflation now making her budget even tighter, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can. I find myself going into stores and saying, ‘No, I don’t need that,’” Seeley said. “The biggest worry I have is not being able to afford living in my home or becoming ill. I know that medical expenses could wipe me out in no time financially.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News Reporter.

khn.navigatingaging@gmail.com, @judith_graham