C. David Thomas is a Wellesley, Mass.-based artist.

William Morgan: Cutting-edge artisanship at a family homestead in rural Maine

Hannah and Chris Blackburn outside their cutting-tool-making workshop, in New Gloucester, Maine

— All photos by William Morgan

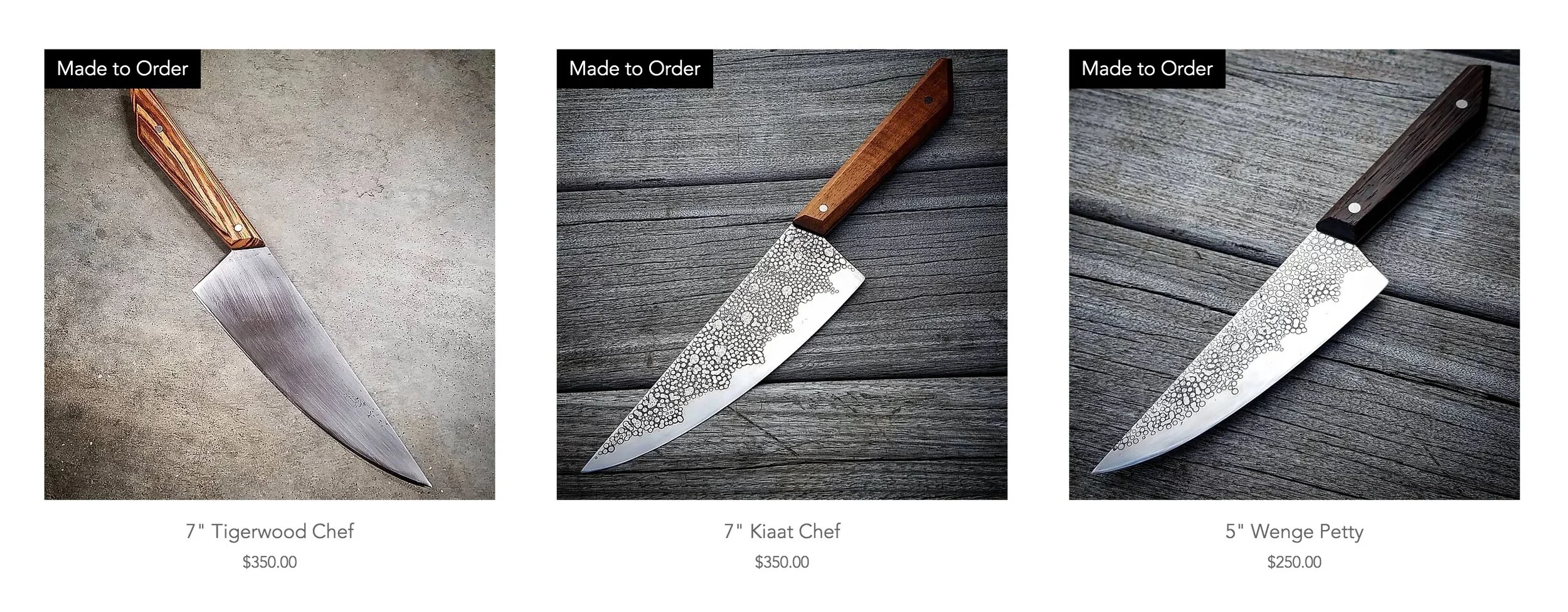

My wife recently bought herself a kitchen knife. Carolyn has dozen of blades suited to all kinds of cooking and pottery, including the stained and pitted Sabatier that she found at a yard sale a quarter century ago. But this piece of cutlery from Maine was different. It cost far more than she could afford, but it was so beautiful, such a work of art, that she could not afford not to buy it.

Really good tools should have stories. Carolyn's new extension of her hand was made of recycled materials: wood from Boston park benches and metal from old saw blades (the recycled 19th Century carbon steel is much stronger than anything available now, and its hard-earned patina is beautiful). That these artisanal tools are sold only at two stores –Strata in Portland and Stock in Providence – reinforces the fact that they’re the products of true craftspeople.

The Blackburns use the steel from old saw blades to make their artisanal knives and other cutting tools.

Full Circle CraftWorks is the commercial face of two art school graduates, trying to build a business while raising a family on a 22-acre homestead in New Gloucester, Maine, a quiet upland town close to, but very different from Freeport, best known for L.L. Bean and other stores, many of them outlets of national chains.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn met as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design, where they were furniture and sculpture majors, respectively. They mastered such skills as welding and sculpting, along with traditional woodworking. Maine native Hannah grew up in nearby Yarmouth, while Chris hails from suburban Washington, D.C. After graduation, the couple remained in the Rhode Island capital.

Providence is a good place for young artists, with lots of colleagues and abundant studio space, but its urban setting was not what the Blackburns wanted for their growing family of two girls and a boy. "The goal was to carve out a simpler life," Chris says, "more directly connected to the environment, the seasons, and all things that sustain our life." One grace note is that the quest for a life based on the land while producing beautiful utilitarian objects is not so different from that espoused by the Shakers, whose last active colony, Sabbathday Lake, is close by in New Gloucester.

Carolyn Morgan and Chris Blackburn in First Circle’s workshop

Their 1985 log cabin on a dirt road came with a two-stall horse barn, which they converted into a workshop, complete with enough of the tools needed to fashion the exotic woods from around the world and the redundant saw blades from barns and country auctions into their handsome tools.

The future success of Full Circle would let these artists live from their sales, but right now their main goal is raising a family on what they hope will become a thoroughly sustainable operation. As a result, much of their life is focused on the rigorous, endless day-to-day and seasonal activities of a working farm.

Just a mention of the Full Circle’s livestock – three goats, seven ducks and a score of chickens, guarded by a dog to guard against coyotes, bears and other predators – ought to be reminder enough that self-sufficient farm life is far from simple or romantic. In the spring, piglets, turkeys and more laying hens augment the permanent stock. Bow hunting deer in the autumn provides much of the family's meat.

There is a small greenhouse, a fruit orchard and gardens for a variety of crops that will grow in Maine. The house and workshop are heated solely with firewood harvested on the property, where sugar maples are tapped to make syrup. Through all the seasons the three young children, aged nine, seven and five, help with chores, from planting and harvesting, to stacking firewood and feeding the animals.

Demanding as farm life is, it does not preclude the family's engagement with the local community. The Backburns host an annual July pig roast that draws scores of friends and neighbors. Their two daughters act in plays put on by the local youth theater, where Chris is a set designer and member of the build crew. The Blackburn children go to a Montessori-type charter school, even as important life lessons come from being part of the agricultural enterprise that helps sustain them.

A hand saw once used in Massachusetts apple orchard or a large circular blade from a Vermont sawmill, along with wood repurposed from repairing their cabin's porch or from an Indonesian rainforest, are transformed into utilitarian but strikingly handsome tools. Whether Hannah and Chris are fashioning a cleaver or a chopping blade, their handmade tools express a worldview that respects the land and the dignity of hard work.

When Chris saw Carolyn's knife again, he said, "It's getting good use; I can tell by the patina. I much prefer that. Some people see them as precious, but tools need to be used."

William Morgan, based in Providence, is an architecture writer, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Gloucester. It was founded in 1783 by the United Society of True Believers at what was then called Thompson's Pond Plantation. Today, the village is the last of some over two-dozen religious societies, stretching from Maine to Florida, to be operated by the Shakers themselves. It comprises 18 buildings on 1,800 acres.

Retail outlet business fading in N.E.

Street scene in 2012 during a street fair in Freeport, Maine, perhaps New England’s most famous retail outlet town. Business has been sliding since then.

— Photo by Dirk Ingo Franke

—

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Quite a few New England towns, such as Freeport (home of L.L. Bean) and Kittery, Maine, Westbrook, Conn., and Wrentham, Mass., have long positioned themselves as venues for higher-end retail outlets for national brands and gotten a hell of a lot of tax revenue from them. But Amazon and other online retailers are taking big bites out of them and many stores are closing. Some of the vacant space is being rented by local stores, but paying much lower rent than the prestige national brands did.

Housing is too expensive for many people. So how much of this dead retail space can be converted to housing; and if all or most of the stores now in these outlet malls close, can they be reconfigured into latter-day, mostly residential village centers or have to be demolished?