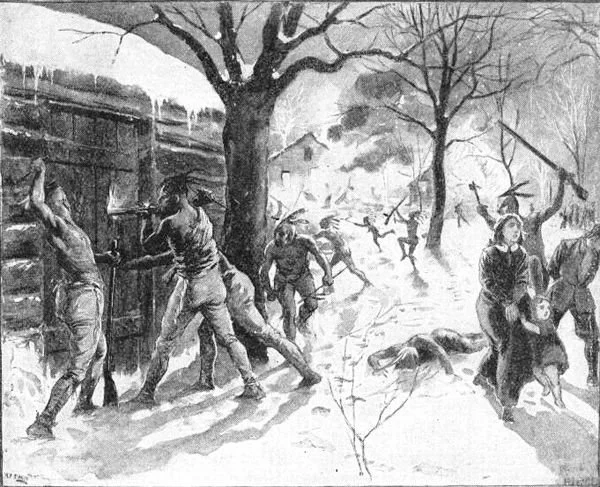

In less than seven years this Sacred Lotus patch has taken over nearly two acres of 12-acre Meshanticut Pond, in Cranston, R.I.

— R.I. Department of Environmental Management photo

From ecoRI News (ecori.0rg)

When a Cranston, R.I., resident planted a Sacred Lotus in the pond at Meshanticut State Park in memory of a family member in 2014, she didn’t realize that the plant was an aggressive invasive species. The lotus, which features enormous floating leaves that shade out native plants, quickly took over a large area of the Rhode Island pond.

Five years later, 75 volunteers spent 12 hours cutting it back, but they eradicated just 10 percent of the ever-expanding plant, which today covers 1.83 acres of the 12-acre pond.

It’s one of many examples of the challenges the state faces in trying to control and eliminate aquatic invasive species. More than 100 lakes and 27 river segments in Rhode Island are plagued with at least one species of invasive plant, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM). These plants pose threats to healthy ecosystems, reduce recreational opportunities, and negatively impact the economy.

“Aquatic invasives are definitely a problem for water quality, but there aren’t a lot of resources dedicated to mapping them and trying to contain them,” said Kate McPherson, riverKeeper for Save The Bay. “The problem is they can show up in really pristine areas of the state for a variety of reasons, and a lot of the plants only need a couple of cells or a leaf to reproduce. They don’t need seeds. So unless you’re really diligent about scrubbing down your boat and other equipment after each use, it’s really hard to prevent their spread.”

In its 2020 fishing regulations, DEM prohibited the transport of invasive plants on any type of boat, motor, trailer, or fishing gear as a strategy to prevent the inadvertent movement of aquatic invasive species from one waterbody to another.

“It’s essentially an incentive for boaters or anglers to clean off their gear to make sure they don’t move any plants unintentionally,” said Katie DeGoosh of DEM’s Office of Water Resources. “It’s part of a national campaign known as Clean Drain Dry to remind anyone recreating on water how they should decontaminate their gear to avoid spreading invasives.”

DEM’s latest effort to combat aquatic invasive species is proposed regulations to ban their sale, purchase, importation, and distribution in the state. Rhode Island is the only state in the Northeast that has yet to regulate the sale of these plants.

The proposed regulations have the support of Save The Bay, the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, and the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society.

Those with aquatic plants in backyard water gardens aren’t the focus of the regulations because those residents aren’t selling the plants, DeGoosh said.

A mat of Water Chestnuts in Olney Pond at Lincoln Woods State Park limits the amount of light available to other aquatic plants, allowing it to quickly displace native species and decrease biodiversity. (DEM)

The proposed regulations list 48 species of aquatic invasive species whose sale would be prohibited. All but one — Sacred Lotus — are included on the Federal Noxious Weed List, are banned by other states in the region, were nominated by the Rhode Island Invasive Species Council or are included in the Rhode Island Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan.

Among them are Carolina Fanwort, a problem species in numerous locations, such as Stump Pond in Smithfield; American Lotus, which covers 18 acres of Chapman Pond in Westerly; Brazilian Waterweed, which has invaded Hundred Acre Pond in South Kingstown; and common Water Hyacinth, an Amazonian species now found in the Pawcatuck River in Westerly.

Perhaps the worst of them is Variable Milfoil, which has been recorded in 69 lakes and ponds and 19 river segments in Rhode Island.

“Milfoil means a million tiny leaves,” said McPherson, who monitors local rivers for invasive species. “It looks like a submerged raccoon tail, and if you’ve been paddling in any pond in Rhode Island, you’ve probably seen it. A tiny little fragment can spread it.”

In many waterbodies, especially in urban communities, multiple species of aquatic invasives have colonized.

“They’re a problem because they can choke out native species and they may not be as good a food source for animals that eat aquatic plants,” McPherson said. “They’re also indicative of a water-quality problem. We’re seeing them more commonly in areas with too much phosphorous or nitrogen in the water. Areas with pollutants encourage these plants to grow.”

David Gregg, executive director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, also noted the impact of pollution in helping aquatic invasives take hold.

“People really care about their lakes, but most lakes in Rhode Island are man-made, shallow, and polluted by surrounding development — lawns, septics, road runoff — and so they grow invasive plants like nobody's business,” he said.

Like at Meshanticut Pond, once the plants become established in a waterbody, they are difficult to eradicate.

“It’s a cyclical problem,” McPherson said. “It’s super satisfying to go as a volunteer to rip it out, and super discouraging to go back a year later and find that it’s still there. If you don’t get all of the root system, it grows back.”

Natural History Survey staff documented the first occurrence of invasive water chestnut in the state in 2007 at Belleville Pond in North Kingstown. They led numerous volunteer efforts to manually remove it every year for a decade, and yet the plant remains. A similar endeavor to battle water chestnut at Chapman Pond in Westerly barely made a dent in the abundance of the plant.

“It’s a big problem,” McPherson said. “We need to get folks to think about how their activities can spread the plants and get them to think about aquatic invasives as a kind of contaminant.”

The proposed regulations, if approved, would be enforced via business inspections by DEM staff. Violators could be fined up to $500 per violation.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.