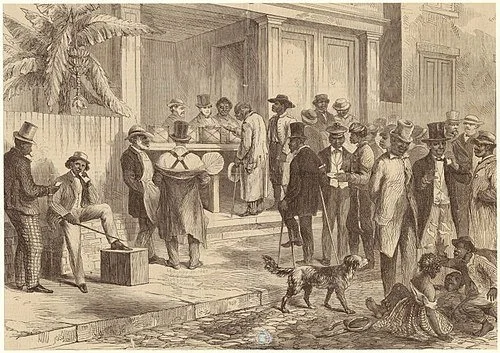

Former slaves voting in New Orleans in 1867. After Reconstruction ended, in 1977, most Black people in much of the South lost the right to vote and didn’t regain it until the 1960s.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

“Reconstruction” (1865–1877), as high school students encounter it, is the period of a dozen years following the American Civil War. Emancipation and abolition were carried through; attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery; and problems were resolved involving the full re-admission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded.

The latter measures were more successful than the former, but the process had a beginning and an end. After the back-room deals that followed the disputed election of 1876, the political system settled in a new equilibrium.

I’ve become intrigued by the possibility that one reconstruction wasn’t enough. Perhaps the American republic must periodically renegotiate the terms of the agreement that its founders reached in the summer of 1787 – the so-called “miracle in Philadelphia,” in which the Constitution of the United States was agreed upon, with all its striking imperfections.

Is it possible that we are now embroiled in a third such reconstruction?

The drama of Reconstruction is well documented and thoroughly understood. It started with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, continued with his Second Inaugural address, the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox Courthouse; emerged from the political battles Andrew Johnson’s administration and the two terms of President U.S. Grant; and climaxed with the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution – the “Reconstruction Amendments.” It ended with the disputed election of 1876, when Southern senators supported the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, in exchange for a promise to formally end Reconstruction and Federal occupation he following year.

The shameful truce that followed came to be known as the Jim Crow era. It last 75 years. The subjugation of African-Americans and depredations of the Ku Klux Klan were eclipsed by the maudlin drama of reconciliation among of white veterans – a story brilliantly related in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, by David Blight, of Yale University. For an up-to-date account, see The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, by Eric Foner, of Columbia University.

The second reconstruction, if that is what it was, was presaged in 1942 by Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation. The political movement commenced in 1948 with the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. The civil rights movement lasted from Rosa Parks’s arrest, in 1955, through the March on Washington, in 1963, at which Martin Luther King Jr. made delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, and culminated in the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Repression was far less violent than on the way to the Jim Crow era. There were murders in the civil rights era, but mostly they made newspaper front pages.

And while the second reconstruction entered on race, many other barriers were breached in those rears as well: ethnicity, gender and sexual preference. In Roe v Wade the Supreme Court established a constitutional right to abortion a decade after the invention of the Pill made pregnancy a fundamentally deliberate decision.

How do reconstructions end? In the aftermath of decisive elections, it would seem – in the case of the second reconstruction, with the 1968 election of Richard Nixon, based on a Southern strategy devised originally by Barry Goldwater. Nixon was in many ways the last in a line of liberal presidents who followed Franklin Roosevelt. He had promised to “end the {Vietnam} war” the war and he did. An armistice of sorts – Norman Lear’s All in the Family television sit-com – preceded his Watergate-inspired resignation. Peace lasted until the election of President Barack Obama.

So what can be said about this third reconstruction, if that is what it is? Certainly it is still more diffuse – not just Black Lives Matter, but #MeToo, transgender rights, immigration policy and climate change, all of it aggravated by the election of Donald Trump. This latest reconstruction is often described as a culture war, by those who have never seen an armed conflict. How might this episode end? In the usual way, with a decisive election. Armistice may takes longer to achieve.

For a slightly different view of the history, see Bret Stephens’s Why Wokeness Will Fail. We journalists are free to voice opinions, but we must ultimately leave these questions to political leaders, legal scholars, philosophers, historians and the passage of time. I was heartened, though, at the thought expressed by economic philosopher John Roemer, of Yale University, who knows much more than I do about these matters, when he wrote the other day to say “I think the formulation of the first, second, third…. Reconstructions is incisive. It reminds me of the way we measure the lifetime of a radioactive mineral. We celebrate its half-life, three-quarters life, etc….. but the radioactivity never completely disappears. Racism, like radioactivity, dissipates over time but never vanishes.”

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian He’s proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.