David Warsh: Three to watch in the mid-term elections

An 1846 painting by George Caleb Bingham showing a polling judge administering an oath to a voter

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

My Fourth of July resolution was to tune out stories about the possible 2024 presidential ambitions of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, and pay attention instead, at least until Nov. 8, to the Senate campaign in Ohio. Author-turned-venture capitalist J.D. Vance and Congressman Tim Ryan are running there to succeed retiring Republican Sen. Rob Portman.

Vance, 37, gained fame as author of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (2016). After high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and served as a public-affairs specialist in an air wing during the Iraq War. He then graduated from from Ohio State University, went on to Yale Law School and then left a corporate-law practice for a venture-capital firm in San Francisco. He returned to Ohio in 2016 to form, with partners, a venture fund of his own. Formerly an evangelical Protestant, he converted to Roman Catholicism in 2019. He opposes abortion rights.

Ryan. 49, is a 10-term congressman whose present district includes much of northeast Ohio, from Youngstown to Akron. In 2015, he explained to readers of the Akron Beacon Journal “Why I changed my thinking on abortion’’. The next year, he led an ultimately unsuccessful effort to unseat Nancy Pelosi as party leader of the House Democrats.

Might Ryan, if he wins, find a seat on that otherwise still all-but-empty bench of potential 2024 Democratic presidential candidates, at whose opposite end sits Clinton? It is plausible, if not likely. After all, former Ohio Gov. John Kasich had a shot at derailing Trump as Republican nominee in 2016. In any event, lie Vance, Ryan seems likely to remain in public life for years to come.

Jane Coaston, a journalist, is a third star rising in the mid-term elections, and probably well beyond. The New York Times hired her away from Vox last autumn to run a weekly discussion show, The Argument. Coaston grew up in suburban Cincinnati, according to Graham Vyse, of The Washington Post, the daughter of union Democrats who were “giant hippies,” before she learned to distinguish among varieties of conservative thought as editor of The Michigan Review at the University of Michigan. She gained prominence with a National Review article in 2017, “What if there is no such thing as Trumpism?” Her talk-show discussion with two leading Republican theorists after Vance’s Trump-endorsed primary victory in May was especially illuminating.

Control of the Senate will almost certainly become the dominant story of the mid-term elections. The Pennsylvania Senate race is interesting, too. To me, at least, it seems likely, that the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade will cost Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) his leadership of the Senate. This column is mostly about economics, but the investigation of preferences change is gradually becoming an important part of economics

Immigration, foreign wars, globalization and climate change: All these national issues will take a back seat in November elections, which are about leadership in particular states. They will resurface, along with women’s rights, in 2024. Harvard Historian Jill Lepore wrote a couple years ago that America, like any other nation-state, requires a “national story.” She was right. Voters write it, election by election.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: The far right's successful fifty-year campaign to pack the Supreme Court

Better when empty? The interior of the U.S. Supreme Court.

— Photo Phil Roeder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the summer of 2005. George W. Bush had been re-elected president the autumn before. He possessed political capital, he exulted, and intended to use it. His inaugural address implicitly defended his invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and, without mentioning his embrace of NATO expansion, went further still: “[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

A popular uprising in Lebanon soon boiled over, was dubbed “the Cedar Revolution,” Syria agreed to end its thirty-year occupation of southern portion of the country, and Newsweek asked, on its cover, “Was Bush Right?”

But the war in Iraq remained bogged down. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice seemed to replace Vice President Dick Cheney as Bush’s closest foreign-policy adviser. The president’s major domestic initiative, a plan to privatize the Social Security System, on which Bush had campaigned since 1978, was abandoned. And in August, Hurricane Katrina flooded and flattened New Orleans.

Bush focused on the Supreme Court.

Sandra Day O’Connor announced her retirement a few months before. Eager to nominate the nation’s first Hispanic Supreme Court justice, Bush’s first choice was his friend and former White House counsel, Atty. Gen. Alberto Gonzales. Objections to his candidacy were raised, from anti-abortion conservatives in particular. So in July Bush nominated federal Appeals Court Judge John Roberts instead.

Within weeks, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, after a lengthy battle with throat cancer. Bush re-nominated Roberts, this time to replace the chief, and to succeed O’Connor, he nominated another old friend, Harriet Miers, a corporate lawyer from Dallas, who had replaced Gonzalez as White House counsel. She was widely criticized for lack of judicial experience.

So, despite his determination to nominate a woman, Bush chose Samuel Alito instead.

In the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama defeated John McCain. The next April, David Souter announced his retirement from the high court and Obama nominated federal Appeals Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor to succeed him. She was confirmed in August. Associate Justice John Paul Stevens retired the year after that, and though Obama was offered bipartisan support for the candidacy of federal prosecutor Merrick Garland, he nominated former Solicitor General Elena Kagan instead.

After Associate Justice Antonin Scalia died unexpectedly, in February 2016, Obama finally sent Garland’s name to the Senate to succeed Scalia, but even with seven months remaining before the November election, it was too late. Senate Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) refused to act on the nomination, and when Donald Trump was elected, it expired. During his term, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to replace Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy. McConnell got all three confirmed by the Senate.

It is not easy to pack the Supreme Court, but, working diligently, over a period of fifty years, a coalition of conservative lawyers, evangelical Christians and Catholic activists, had finally succeeded.

I was reminded of all this when I took down from the shelf The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: the Battle for the Control of the Law (Princeton, 2008), by Steven Teles, of Johns Hopkins University. Of particular salience was the early chapter on “The Rise of the Liberal Legal Network,” in which Teles describes as the conjunction of the Supreme Court led by Earl Warren and the development of an extensive supportive structure in law schools during the Rights Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s.

After that, this splendid book describes nearly everything you need to understand about the counter-mobilization that developed in the 1970s and 1980s: the advent of conservative public interest law in the early 1970s (and the early mistakes from which its institutions learned); the origins of the law and economics movement and its institutionalization by Henry Manne; the counter-networking since 1982 of the Federalist Society. There is a lot of history to imbibe in order to understand how the movement .achieved its most cherished goal last week.

On the other hand, if you want a glimpse of where the intermingling of law and economics is headed, read Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics (Princeton, 2018), by Kaushik Basu, of Cornell University. Basu is a development economist, former chief economist of the World Bank (as were Paul Romer, Joseph Stiglitz and Anne Krueger), and, like them, a theorist; in his case, a student and collaborator of Amartya Sen and Anthony Atkinson. Basu expects focal points, a concept derived from game theory to play a central role in rethinking the relationship between economics and law. (Better, perhaps, to call it the study of interactive decision-making.)

What’s a focal point? You know one when you see one: shared manifestations of a psychological capacity, prevalent among humans, especially those who share common cultural backgrounds, which enables individuals to guess what others are likely to do, when faced with the problem of choosing from one among several possible options. A classic example? The decision whether to drive on the left or the right side of the road.

But that’s story for another day; a project for the next fifty years.

Meanwhile, if you are simply looking for the damaged but still-healthy roots of the mainstream Republican Party, the place to start is with Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion in the cases last week, in which he dissented from the “relentless freedom from doubt” displayed by his colleagues in their majority decisions last week:

The Court’s decision to overrule Roe and Casey {abortion cases} is a serious jolt to the legal system – regardless of how you view those cases. A narrower decision rejecting the misguided viability line would be markedly less unsettling, and nothing more is needed to decide this case.

George W. Bush’s original two preferences for the high court– Gonzales and Miers – surely would have concurred, had they been nominated and confirmed as associate justices. Roberts, it seems to me, had become the de facto leader of the old version of the Republican Party, U.S. Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyoming) its floor leader in Congress. If you want to know what will happen next, bide your time until autumn and carefully sift through the mid-term election results. Then fasten your seat belts for 2024.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Of financial revolutions

The Prince of Orange landing at Torbay, England, in the Glorious Revolution that overthrew James II and installed the Prince of Orange, a Dutchman, as William III.

— Painting by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Many people at least a little about the history of the scientific revolutions of the 16th and 17th centuries; the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries; and the democratic revolutions of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Very few are familiar with the major details of the financial revolution of the early 18th Century, which began with the reforms of England’s “Glorious revolution” of 1688. In the course of the next sixty years, these developments brought into existence the modern military-industrial complex.

This relative obscurity of these long-ago events is not surprising, for, as best I can tell, the term had no currency before Peter G.M Dickson, in 1967, published The Financial Revolution in England: A Study of the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756. Until then, the power to spend public money was colloquially described as “the control of the purse.”

It is, however, something of a shame, since what we now call “the national debt” these days is the engine that powers military interventions around the world, from the misadventures of the George W, Bush administrations forays in Afghanistan and Iraq to Vladimir Putin’s quagmire plunge in Ukraine. You can’t fathom those periodic $60 billion appropriations bills without knowing something about the enormous multinational purse that supports NATO.

Instead, our understanding of these matters depends on combinations of vignettes and modern analysis, a sauce that often doesn’t come together.

Among vignettes, an especially appealing recent example is Ways and Means: Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, by social historian Roger Lowenstein. It relates how Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln’s defeated presidential rival, turned the tide of war against the South on the financial front, “levying taxes and marketing bonds, while desperately batting inflation.” A more encompassing account of government bond markets was related twenty-five years ago and updated in 2010 in Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, by John Steele Gordon.

A welcome addition among analytics In Defense of Public Debt, by Barry Eichengreen, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves, and Kris James Michener (2021), a hard-headed survey of debt in the service of the state and what’s known about the limits of borrowing. The wind has largely gone out of the sails of the fad called “modern monetary theory,” thanks to books like this, and the papers cited herein. And the book synthesizes a good deal of valuable history. But the topical treatment of the issues is unlikely to make an impression on the broad public mind. That take a lifetime of research in the manner of Dickson, or, in the case of the cadre of researchers working over insights derived from a famous 1989 article about the origins of modern democracy, by Douglass North and Barry Weingast.

Thus the lack of understanding is of the financial revolution is to some degree the story of a lost book. Dickson died last year, having spent sixty years as a Founding Fellow of St. Catherine’s College, Oxford University. He revised his English Financial Revolution book in 1993, but that second edition is out of print. Even the library copy of the original was missing when I arrived yesterday. You can get some idea of the scope of the problem from its table of contents — and why the story of government bond markets is a hard tale to tell.

The Financial Revolution — 2. The Contemporary Debate — II. Government Long-Term Borrowing — 3. The Earliest Phase of the National Debt 1688-1714 — 4. Problems of Administration and Reform 1693-1719 — 5. The South Sea Bubble (I) — 6. The South Sea Bubble (II) — 7. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 8. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 9. The National Debt under Walpole – 10. War and Peace 1739-1755 — 11. Public Creditors in England and Abroad– 12. Public Creditors Abroad – 12. Government Short-term Borrowing — 13. Borrowing by Exchequer Tallies — 14. Borrowing by Exchequer Bills — 15. Departmental Credit — 16. The Bonds of the Monied Companies — 17. The Ownership of Short-dated Securities and the Market in Securities — 18. The Turnover of Securities — 19. The Rate of Interest in Theory and Practice — 20. The Origins of the Stock Exchange

A parallel history of events in France adds dimensionality to the story. French Finances, 1770-1795; From Business to Bureaucracy (1970), by John F. Bosher, describes role of the French Revolution in transforming a thoroughly corrupt system of government finance into a less venal and more efficient system. In A Financial History of Western Europe (1993), Charles P. Kindleberger, who assigned the two books in courses he taught in 1979 and 1980, wrote, “Note that the financial revolution of England preceded that of France by a century, and that the view that British military success owed to her financial capacity is matched by the statement that financial incompetence of the French monarchy was the main reason for its ultimate collapse.”

The good news is that not one but two top-flight economic historians are once again working on telling the story of the revolution charted by Dickson fifty years ago. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution 1688-1720, by Carl Wennerlind, of Barnard College, at Columbia, was under-appreciated when it appeared ten years ago. The author bent over backwards to avoid triumphalism by incorporating, as the financial revolution’s first great success, the story of Britain’s entry into the Atlantic slave trade – the usually glossed-over precipitant and still-less-remembered outcome of the South Sea Bubble.

Anne L. Murphy, of the University of Portsmouth, who spent twelve years working trading interest-rate and foreign-exchange derivatives in the City of London, re-tooled as a historian and published The Origins of English Financial Markets: Investment and Speculation before the South Sea Bubble in 2009. The book won the Economic History Society’s best monograph prize the next year. She is preparing to publish Virtuous Banking: a day in the life of the late eighteenth-century Bank of England.

Meanwhile, Wennerlind’s new book, A Philosopher’s Economist: Hume and the Rise of Capitalism, co-authored with Margaret Schabas, of the University of British Columbia, appears next month. The financial revolution of the eighteenth century is with us every day. The extent and significance of its evolution has yet to be fully spelled out to a 21st Century audience.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: What Putin had hoped in assaulting Ukraine

St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Boston.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Two days into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the dispatch from Russia’s state-owned news service seemed to reflect Vladimir Putin’s innermost reasoning.

A new world is coming into being before our very eyes. Russia’s military operation has opened a new epoch…. Russia is recovering its unity – the tragedy of 1991, this horrendous catastrophe in our history, its unnatural caesura, has been overcome. Yes, at a great price, yes through the tragic events of what amounts to a civil war, because now for the time being brothers are shooting one another… but Ukraine as anti-Russia will no longer exist.

Instead, the Novosti account continued, the Great Russians, the Belarusians and the Little Russians (Ukrainians) would come together as a whole – a reconstituted Russian Empire. Putin had undertaken the “historic responsibility” of reunification upon himself “rather than leaving the Ukrainian question to future generations.”

The pronouncement was quickly taken down, according to Jonathan Haslam, Kennan Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, N.J., describing Putin’s Premature Victory Roll in early March. It wasn’t just the over-optimism that rendered it embarrassing. It was too transparent. The goal of reunification superseded Putin’s usual complaint about the threat to Russia posed by NATO expansion.

I was broadly sympathetic to Putin after 1999, when he published his essay on Russia in the Twenty-First Century as an appendix to his First Person interview in 2000, upon taking office. I overlooked the Second Chechen War. I began paying attention after he criticized the U.S. for its invasion of Iraq in a speech in Munich, in 2007. Even after Putin’s seizure of the Crimean Peninsula, in 2014, he seemed to be within his rights, though barely. Russia had a historic claim on the peninsula on which its Black Sea naval base in Sebastopol in situated, I reasoned.

No more. Last week I re-read Putin’s article from last August, On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Then I read When history is weaponized for war, historian Simon Schama’s scathing criticism of it, When the Pope sought to give Putin an excuse for his invasion, in an interview with an Italian newspaper earlier this month, asserting that NATO had been “barking at Russia’s door,” it rang hollow. Nobody is talking about a Morgenthau Plan for Russia after the war in Ukraine, but nobody is talking about a Marshall Plan, either. It has options – a stronger alliance with India? But regaining its reputation in Europe looks harder than ever.

NATO’s long-term strategy of “leaning-in” seems to have worked. Putin may or may not have cancer, as a report suggested yesterday in The Times of London, but something has seriously wrong gone wrong with the man. Haslam cites Shakespeare. Putin has waged a war he cannot win. He is cementing in place the fence around him of which he complained.

Consider that his war on Ukraine has persuaded Finland and Sweden to seek to join NATO.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran. He’s the author of, among other books, Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years.

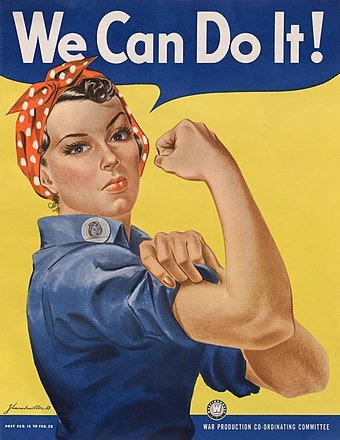

David Warsh: The expansion of women’s economic freedom that helped lead to Roe v. Wade

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The circumstances that gave rise to the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, to establish physicians’ right to counsel the possibility of medical abortion, are not easy to recall. There was so much turmoil on the surface of things fifty years ago – Vietnam, Watergate, Richard Nixon’s landslide re-election. In retrospect, one skein of developments stands out as more momentous than the rest: the rapidly changing opportunities available to American women.

For that reason, there is no better place to start than with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin’s Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). A distinguished economic historian, Goldin organized her account around the experiences of five roughly defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the 20th Century. Each cohort merits a chapter.

The revolution, Goldin finds, was a technological one: the advent in the Sixties of dependable methods of birth control – the Pill, the IUD and the diaphragm. Women began re-entering the workforce on new terms. After explicating the traditional logic of early marriage – perhaps timeless, evolutionarily speaking – Goldin writes:

Armed with the new secret ingredient, the recipe for success became, “Put marriage aside for now. Add gobs of higher education. Blend with career. Let rise for a decade, and live tour life fully. Fold family in later.” Once this happiness formula was adopted by large numbers of women, the age at first marriage increased, even for college women who did not take the Pill. That reduced the potential cost of long-run cost of marriage delay for any one woman.

With that, the 7-2 majority decision in Roe v. Wade was almost an afterthought. The Supreme Court doesn’t just follow the election returns; they have families, and read the newspapers as well. .

Since 1982, the Federalist Society, conservative legal representatives of that year’s “Silent Majority,” have been working to reverse the decision by fundamentally transforming the judicial interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. You can read historian David Garrow’s triumphant summary of these “originalist” and “textualist” movements here.

Meanwhile, a May 7 Boston Globe story (subscription required) about Sir Matthew Hale, the 17th Century jurist whom Associate Justice Samuel Alito cited more than a dozen times in his 98-page draft opinion, makes equally interesting reading. Reporter Deanna Pan may have surfaced another plausible reason that the draft was leaked.

If experience is any guide, the next twenty-five years will see an avalanche of work on the other side of the argument, produced by legal scholars, historians, economists and other social scientists. Quite apart from whatever the election returns in the coming years might be, a movement to explain changing values and preferences has been underway in economics for years. New views on the joint evolution of institutions and cultures are entering the mainstream.

The Supreme Court is one of those institutions – central banks are another – to which democratic societies have delegated decision-making powers in the hope that in difficult times they will make more far-sighted policy choices than those of the current majority.

The court decided Roe v, Wade correctly in 1973. In all likelihood, it will sooner or later rise to the occasion again, In the meantime, stay calm; plan ahead, and cope with consequences if the expected reversal eventuates. Don’t throw the Supreme Court baby out with the bathwater.

David Warsh a veteran reporter, columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

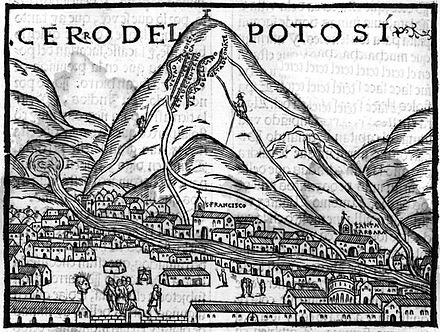

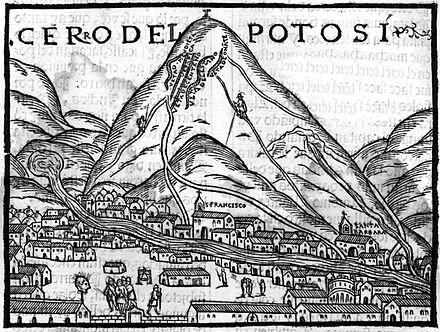

David Warsh: Money follows development and vice versa

Cerro Rico del Potosi, the first European image, in 1553, of a silver-ore-rich mountain in what became Bolivia. It was heavily exploited by Spain.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

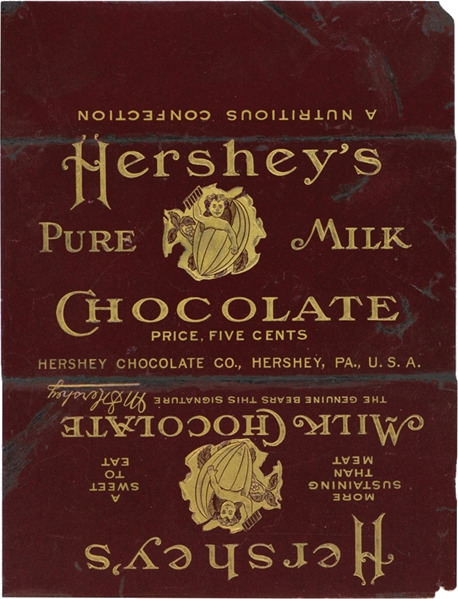

A candy bar that cost a nickel in 1950 today costs $1.25 or so, depending on where you buy it. That, in a paper wrapper, is the price revolution of the 20th Century. Why did it happen? The answer usually given is that the quantity of money increased – too much paper money chasing too few candy bars.

A more satisfying explanation, casual though it may be, is to recognize that the global economy has grown considerably more complex since 1950, and the system of money, banking, and credit more complex along with it. The price of the candy bar wasn’t going to return to its previous level, no matter what the Fed or the candy-manufacturers did.

I’ve believed this for forty years, since writing The Idea of Economic Complexity, which appeared in 1984. While nothing has happened to change my mind, it has been interesting, at least to me, to have spent a few Saturdays thinking about what I have learned since then. Let me sum it up with a last few words of explanation, before putting it away.

At the moment, the jolt to increased economic complexity has to do with Russia’s war on Ukraine, the post-Cold War expansion of the NATO alliance and long-lasting disruptions of world trade stemming from the COVID pandemic. These “cost-push” factors are more fundamental to today’s rising prices, I believe, than whatever misjudgments that monetary authorities have made in responding to them. But arguing about recent events is the wrong way to develop views about phenomena as mysterious as the formation of money prices. For that, long-term developments serve best.

The price revolution of the 16th Century is the best example in the last thousand years of a lengthy, unreversed increase in money prices of everyday things. Its magnitude was modest by current standards; but then, so were monetary systems in those days. Between 1501 and 1650, prices of everyday goods across Europe rose six-fold before leveling off and remaining more or less stable on a new level for the next hundred years.

Practically from the beginning, scholars have argued about whether the discovery of the riches of Spanish America initiated the price revolution, or whether the voyages of discovery were undertaken in response to European events already underway. Jehan Cherruyt de Malenstroit blamed rising prices on shortages of precious metals and the extravagance of kings. In a widely read rejoinder, philosophe Jean Bodin, in 1568, ascribed rising prices to the influence of the treasure of The Americas – such was the beginning of what we have called ever since the quantity theory of money.

Economic historians were still arguing about these matters four centuries later. In American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, Earl Hamilton wrote, in 1934, that an “extremely close correlation” between growth in the volume of gold and silver imports from the New World and commodity prices in Spain “demonstrated beyond question” that the abundance of mines in New Spain was “the principal cause” of the price revolution. In Economic Development and the Price Level, in 1962, Geoffrey Maynard argued the opposite: that money generally adjusts to trade, rather than trade to money. In very different formats, the argument continues today.

“Development” is a bland word with which to describe the difference between the world economy in the time of Columbus and the world today. Economic philosopher David Ellerman has suggested that diversity describes the key difference, grounding his description in information theory; I proposed complexity in that 1984 book. But what is it that has become more diverse or complex? Not until I read “Increasing Returns an Economic Progress” (1928), by Allyn Young, did it occur to me that the growing complexity I had been thinking about were increases, of one sort or another, in the division of labor.

And there I left the subject behind. I was working for a magazine when I began writing about price history, complexity and plenitude, an exotic argument about the tacit assumptions of quantity theory of money, gleaned from reading Arthur O. Lovejoy’s The Great Chain of Being (1936). Magazines are lightweight vessels, quick to maneuver in pursuit of advantage, quick to move on. There was no way I could continue to write about economics.

Fortunately, I made my way to a serious newspaper. I finished the book I had begun, and soon put complexity behind me – until this spring, when I briefly took it out to re-examine it. Meanwhile, I had become an economic journalist, following the profession. I stumble on developments in growth theory, and these, too, eventually became a book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006).

So what have I learned? That journalism is about knowing, whereas economics is about proving. A great deal more truth can become known than can be proved, as physicist Richard Feynman once said. Complexity of the division of labor is still out there. Economists will get to it someday. See, for example, Hendrick Houthakker, “Economics and Biology: Specialization and Speciation” (1955). In the meantime, there are other important stories, happening now.

In case you are feeling unsatisfied, though, remember that five-cent candy bar. Are you comfortable with the too-much-money-chasing-too-few-goods story? Do you believe that the Fed could have prevented the rise in its price? And if wasn’t “inflation,” then what was it? The depreciation of money, relative to goods?

As with the 16th Century voyages of discovery, money follows development and development follows money. If you have only the quantity theory of money to rely on, you don’t know what is going on.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Trying to figure out how to measure ‘inflation’

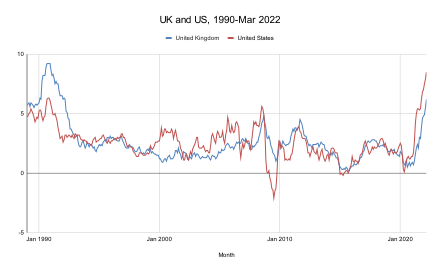

British and U.S. monthly inflation rates from January 1990 to February 2022.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

President Biden calls it Putin’s inflation. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell says the problem began with the pandemic. Harvard University economist Lawrence Summers blames the Fed. Who’s right? Some 250 years of interplay between the science of pneumatics and its technological applications were the background against which economist Irving Fisher, in 1928, expanded the modern usage of the term “inflation” to mean something more than rising prices. Fisher is not a bad place to begin to look for an answer.

Arguments about whether or not such a thing as a vacuum can exist; quicksilver (meaning mercury); barometers; j-tubes; air pumps; valves, cylinders, and plungers; hot air balloons; footballs; the discovery of inert gases (starting with helium); the manufacture of incandescent light bulbs; pressure cookers; inflatable tires – these topics or objects became familiar before Fisher took advantage of relationships among pressure, volume, and temperature of gases, itself by then vaguely understood, in order to attach a new meaning to an old word.

“Anyone… reading [The Money Illusion] (Adelphi, 1928) by Fisher, or other books on monetary affairs published in this period, may have some difficulty with terminology” wrote Fisher’s biographer, Robert Loring Allen, many years after the fact. “For more than a generation, the words ‘inflation’ or ‘deflation’ [had] usually meant increasing or decreasing prices.” But in The Money Illusion. Allen wrote, Fisher coined new meanings: “the words inflation and deflation refer to the money supply, not to prices. Money inflates and in consequence prices rise and a deflation in the money supply causes falling prices.”

It was the first and only book about the subject that Fisher, a prominent Yale University professor and tireless reformer, would write for the general public. He was at pains to explain what he meant.

As I write, your dollar is worth about 70 cents. This means 70 cents of pre-war buying power. In other words, 70 cents would buy as much of all commodities in 1913 as 100 cents will buy at present. Your dollar now is not the dollar you knew before the War. The dollar always seems to be the same but it is changing. It is unstable. So are the British pound, the French franc, the Italian lira, the German mark, and every other unit of money. Important problems grow out of this great fact – that units of money are not stable in buying power.

A new interest in these problems has been aroused by the recent upheaval in prices caused by the World War. This interest nevertheless is still confined largely to a few special students of economic conditions, while the general public scarcely yet know that such questions exist.

Why this oversight?.. It is because of “the Money Illusion”; that is, the failure to perceive that the dollar, or any other unit of money, expands or shrinks in value. We simply take it for granted that “a dollar is a dollar” –that “a franc is a franc” that all money is stable, just as centuries ago, before Copernicus, people took it for granted that that the earth was stationary, that there was really such a fact as a sunrise or a sunset. We know now that sunrise and sunset are illusions produced by the rotation of the earth around its axis, and yet we still speak of, and even think of, the sun rising and setting!

Fisher is at pains to illustrate the illusion. He visits Germany with an economist friend, where the two interview 24 men and women. Only one considered that rising prices have anything to do with the government’s management of its currency.

They tried to explain it by ‘supply and demand’ of other goods, by the blockade; by the the destruction wrought by the War; by the American hoard of gold; by all manner of other things – exactly as in America when, a few years ago, we talked about “the high cost of living,” we seldom heard anybody say that a change in the dollar had anything to do with it.

Fisher went on to explain the system of gold, paper money, and bank “deposit currency,” as bank credit was known at the time. He noted that the Federal Reserve System had recently taken responsibility for the oversight of the money supply that occurred via the purchase and sale of government bonds by its Open Market Committee. He noted the suspension of the international gold standard during the World War and recommended its early resumption. Above all, he urged the adoption of price indices, carefully collected by government agencies, with which to measure changes in “the cost of living,” or, as he puts it, “fluctuations in the value of money.”

But the year was 1928. A world-wide boom was on. Fisher was already somewhat isolated from his university colleagues by his enthusiasm for business (he had sold his Rolodex card-filing system to Remington Rand Corp. and was trading millions in stocks). When the Depression began, instead of hedging his bets, he pursued business as usual a little while longer, and gradually lost his entire fortune. Meanwhile, economists turned their attention to John Maynard Keynes.

“It was particularly unfortunate,” Robert Dimand, of Brock University, has written, “that Fisher lost the attention of the economics profession, the public, and even his Yale colleagues just when he has something interesting to say about with what had gone wrong with his predictions and the economy,” to wit his article “The Debt-deflation Theory of the Great Depression” in the first volume of Econometrica, in lieu of an Econometric Society presidential address. He died in 1947.

But Fisher’s espousal of the value of index numbers to monitor variations in purchasing power stuck, as did his enthusiasm for the monetary, as opposed to real, explanation of rising prices. In Monetary Illusion, Fisher never mention Boyle; he offers a more homely analogy instead: “If more money pays for the same good, their price must rise, just as if more butter is spread over the same slice of bread, it must be spread thicker, the thickness representing the price level, the bread the quantDity of goods.” Twenty five years later, though, a master expositor of Keynesian economics, George Shackle, of Liverpool University, wrote,

How did we come to adopt the portentous word “inflation” to mean no more than a general rise in prices? I think this usage must have had its origin in a particular theory of the mechanism or cause of such a rise. When a given weight of gas is released from a steel cylinder into a large silk envelope, there may appear to be more gas, but in important senses, the amount of gas is unchanged. In a somewhat analogous way, we can make our total stock of currency spread over a larger number of paper notes, but this action in itself will not increase the size of the basket of goods (where various good are present in fixed proportion) that this total stock of currency would exchange for in the market…. Some such image as this may perhaps have been n the mind of the man, who first spoke of inflating the currency. This idea, that the general price level is closely related to the ostensible, apparent size of the money stock… has become formally enshrined in what is called the Quantity Theory of Money.

It’s been nearly 40 years since I published The Idea of Economic Complexity. What have I learned, in all the years since, about explaining generally rising prices? At least this: By all means let us continue to measure money and talk pneumatics. In hopes of narrowing differences of opinion, though, let us keep looking for something real and general in the economy to measure as well. I expect that the Fed has made a pretty good beginning on that.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Searching under streetlights for economic answers

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a young magazine writer, I was a quick enough study to recognize that, in the discussion of inflation, the bourgeoning enthusiasm for monetary analysis had loaded the dice in favor of the quantity theory of money. New World treasure, paper money, central banking: it was as if monetary policy was a force independent of whatever might be happening in the economy itself. It reminded me a famous New Yorker cartoon, a patient talking to his psychoanalyst: “Gold was at $34 when my father died… it was $44 when I married my wife… now it’s $28, but I have trouble seeing.”

I wanted to suggest a variable that might represent the perspective of real analysis, though I did not yet know the term: the conviction, as I learned Joseph Schumpeter had described it, that “all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them,” and that money entered the picture as just another a technological device. Thinking about all else besides monetary innovation that was new in the world since the 15th Century, I came up with a catch-word to describe what had changed. The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking) appeared in 1984.

It certainly wasn’t theory: more in the nature of criticism, a slogan with so little connection to the discourse of economics since Adam Smith that it didn’t bother specifying complexity of what. But the word had an undeniable appeal. “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

Sure enough: Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, appeared in 1987; Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos and Order, by M. Mitchel Waldrop; and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, by Roger Lewin, followed in 1992; and in the next decade, a whole shelf of books appeared, of which The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Remaking of Economics, by Eric Beinhocker, in 2006, was probably the most interesting.

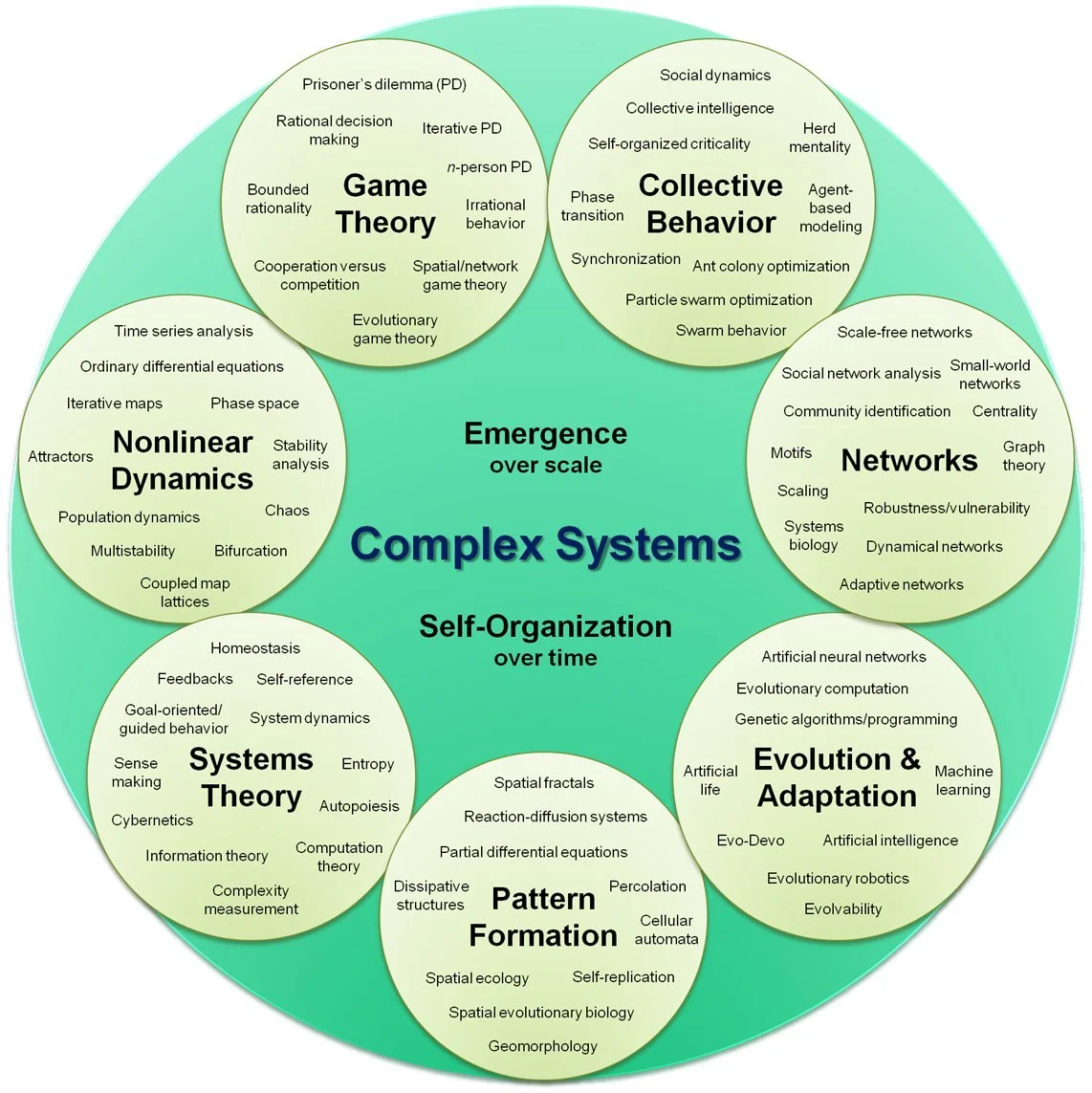

Organizational map of complex systems broken into seven sub-groups.

— Hiroki Sayama, D.Sc

But the question remained: complexity of what? The long quote-box on the back of the book jacket had put it this way:

To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupation dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques, such a graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of our subject are not our subject here, however. It is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what make the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.

Fair enough, for purposes of journalism. There was however something missing in my discussion: to wit, any real knowledge of structure of technical economic thought. I had come across the economist Allyn Young (1876-1929) in my reading, a little-remembered contemporary of Irving Fisher, Wesley Clair Mitchel and Thorstein Veblen, Schumpeter, and John Maynard Keynes. I classified him, with Schumpeter, as a “supply-sider,” in keeping with the controversies of the early ‘80’s, “locating in the businessman’s entrepreneurial search for markets the most profound impulse toward economic growth.” I added only that “We are coming at it from a slightly different direction is this book.”

It wasn’t until I re-read “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” (for those who have access to JSTOR), in the Economic Journal of December 1928, that it dawned on me that it was complexity of the division of labor that I had been thinking about. A particular passage towards the end of Young’s paper brought it home.

The successors of the early printers, it has often been observed, are not only the printers of today, with their own specialized establishments, but also the producers of wood pulp, of various kinds of paper, of inks and their different ingredients, of type-metal and of type, the group of industries concerned with the technical parts of the producing of illustrations, and the manufacturers of specialized tools and machines for use in printing and in these various auxiliary industries. The list could be extended, both by enumerating other industries which are directly ancillary to the present printing trades and by going back to industries which, while supplying the industries which supply the printing trades, also supply other industries, concerned with preliminary stages in the making of final products other than printed books and newspapers. I do not think that the printing trades are an exceptional instance, but I shall not give other examples, for I do not want this paper to be too much like a primer of descriptive economics or an index to the reports of a census of production. It is sufficiently obvious, anyhow, that over a large part of the field of industry an increasingly intricate nexus of specialized undertakings has inserted itself between the producer of raw materials and the consumer of the final product.

Young, a University of Wisconsin PhD, had taught both Edward Chamberlin and Frank Knight as a Harvard professor, before accepting an offer from the London School of Economics to chair its department, at a time when LSE was looking to further distinguish itself. It was as president of Section F of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he delivered his paper on increasing returns. Then, on the verge of returning to Harvard, he died at in an influenza epidemic. He was 52.

By the time that I re-read Young’s paper, I had met Paul Romer, a young mathematical economist then at the University of California Berkley, who had been working for years on more or less exactly the same questions that Allyn Young had raised in literary fashion fifty years before. Romer introduced me to the distinction economists made between “endogenous” and “exogenous” factors.

Endogenous were developments within the economic system; exogenous were those apparently outside, to be “bracketed” or put aside as matters the existing system hadn’t yet found ways to satisfactorily explain. Only a few years earlier, Robert Solow, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for, among other things, his finding that as much of 80 percent of economic growth in a certain period couldn’t be explained by additional increments of labor and capital. Whatever it was, it was to be expressed as a “Residual,” exogenous to the system of supply and demand.

First in “Growth Based on Increasing Return Due to Specialization,” in 1987, then in “Endogenous Technical Change,” in 1990, Romer solved the problem, employing new mathematics he had acquired to describe it. The magic of the Residual, it turned out, was human knowledge, a non-rival good in that, unlike land, labor, or capital, it could be possessed by any number of persons at the same time. I wrote a book about what had happened; Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton) appeared in 2006. In 2018, Romer, by then at New York University, and William Nordhaus, of Yale University, shared a Nobel Memorial Prize for their work on the interplay of technological development and climate change.

I had been hit by the meatball. I understood why Early Hamilton and John Neff had so little to say to each other, why Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson didn’t agree: they were men searching under streetlights for answers – different streetlights, separated by areas of darkness that had yet to be illuminated. I understood that economists could be trusted to continue to develop their field,

But there were still plenty of questions to be answered, including the one that had bothered me since the beginning. Why do we call rising prices “inflation?”

xxx

One of the joys of writing about the news is that you ordinarily never know where you’re going from one week to the next – reading as well, I expect. Yet from small beginnings last autumn, I have launched a mini-series about some things I have learned since publishing The Idea of Economic Complexity in 1984. Had I known at the beginning what to expect, I would have announced a series, Complexity Revisited. I do so now.

This week is the fourth installment, counting the first piece – about the 700-year wage and price index of Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – that triggered the rest. There will be four more, eight in all. Each piece subsequent to the first is connected to something I discovered later, in the witings of Joseph Schumpeter, Charles Kindleberger, Allyn Young, Steven Shapin and Simon Schafer, Nicholas Kaldor, Hendrik Houthakker, and Thomas Stapleford.

What’s the point? It all has to do with the nature of money – how we control it, how it is accumulated, saved and disbursed. Banking is already thoroughly digitized; the digitalization of money itself looms in the future. It makes sense to go back to first principles. These have to do with central banking, it turns out, perhaps the least understood of major modern institutions of governance.

The need here to think matters through, at least a little, arose in connection with other projects underway, large and small. I don’t apologize for having undertaken the series. I’ve done it twice before over the years, each time with good results. But there is something about the weekly column that wants to stay close to the news, especially in these turbulent times. I can confidently promise not to do it again. Back to the news next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

— Photo by Acabashi

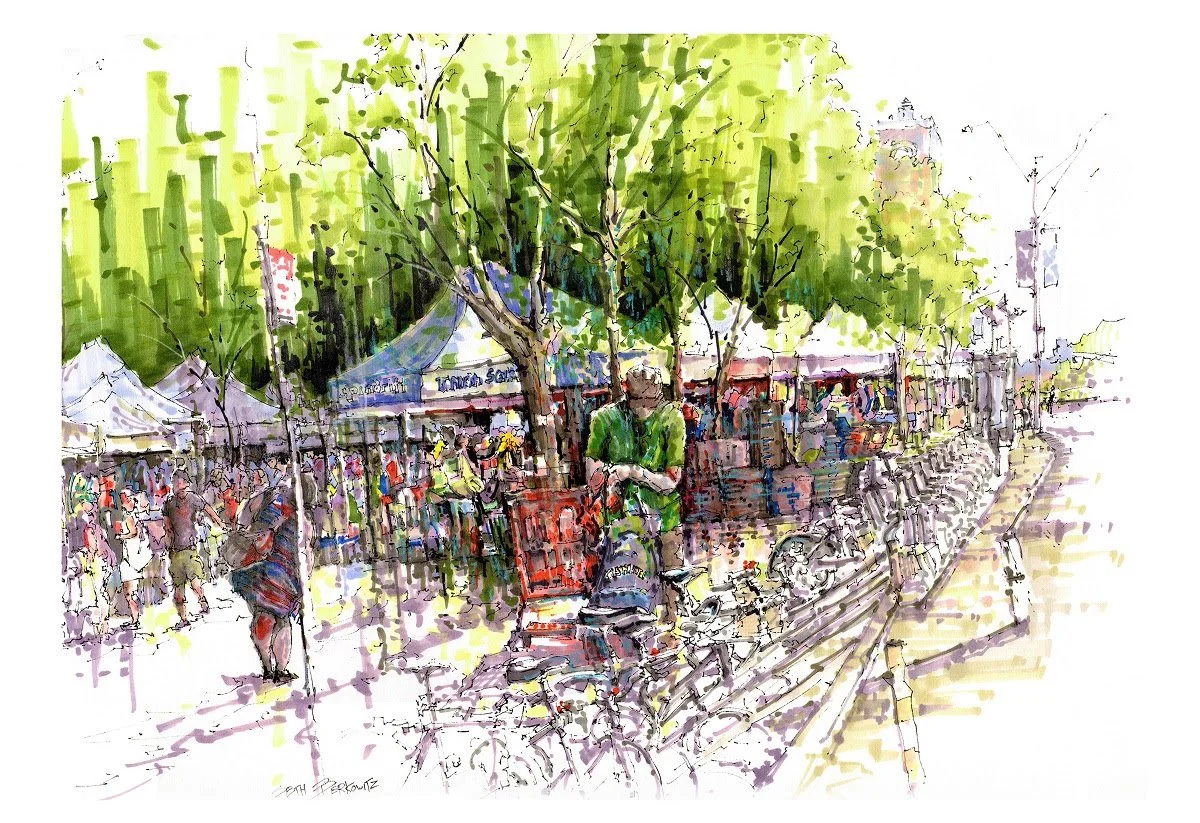

And ‘about meat prices’

The Porter Square Shopping Center in 2009.

“You can’t assume anything in politics. That’s why every Saturday I walk around my district. I talk to the longshoremen in Charlestown. I listen to the people in East Boston and their concern on the airport noise. I walk down to the Star Market in Porter Square, and people tell me about meat prices.’’

— Thomas P. {“Tip”) O’Neill (1912-1994), Massachusetts congressman who served as U.S. House speaker in 1977-87.

The Rand Estate, on site of what is now Porter Square Shopping Center, 1900 or earlier.

From Cuba to Somerville

“Manolete” (bullfighter) (woodcut), by Rafael Zara, in the show “Connections/Conexiones,’’ at Brickbottom Gallery, Somerville, Mass., through April 9.

The gallery explains:

The Brickbottom Gallery is showing original prints by contemporary Cuban artists, most of whom are living on the island. This is the first half of an international print exchange. In 2019, Janette Brossard Duharte, president of the Printmaking section of the Visual Artist Association of Cuba, approached The Boston Printmakers with an idea for an international print exchange. She invited members of The Boston Printmakers to exhibit in Havana and asked the organization to sponsor an exhibit of Cuban artists in the Boston area. The Boston Printmakers happily accepted and the Brickbottom Gallery agreed to exhibit the original prints, never shown here before….

“Brossard brought the work of 37 artists to the gallery from Havana in 2019. The subjects of the prints explore themes ranging from politics to religion to eroticism. The graphic styles run the gamut from realism to colorful abstraction to the printed book. The history of Cuban printmaking began with the necessity to promote Cuban cigars and developed … with the production of strong silkscreen prints to advertise films and to make political statements. Contemporary printmakers have expanded their output to include lithography, etching, woodcuts as well as silkscreen. All of these mediums are present in the Brickbottom Gallery exhibition.’’

David Warsh: Squeezed between pushing democracy and fighting global warming

The Fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, marked a huge turning point in NATO's role in Europe. Here you can see section of the wall displayed outside NATO headquarters, in Brussels.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Which is the more pressing concern: advancing the cause of democracy in the face of opposition, or combatting global warming?

NATO enlargement has been the policy of the United States since Bill Clinton was first elected president, in 1992. The course of action he adopted was embraced and extended by successors George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Was it a good idea?

Anne Applebaum thinks so. The Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist has been among NATO expansion’s most ardent advocates since becoming a correspondent for The Economist, in 1988, and moving to Warsaw. In a panel podcast last week for The Atlantic, where she is now a contributing writer, she said,

I think that the expansion of NATO was the most successful, if not the only successful, piece of American foreign policy of the past thirty years. It created a zone of safety and security for sixty million people in part of the world that has been the source of two world wars…. We would be having this fight in East Germany now if we had not done it.

I have been on the other side of that argument for nearly twenty years, a thin voice in the back of a relatively small chorus of dissenters that included, in 1994, Defense Secretary Les Aspin, his deputy William Perry, and most senior American military commanders at the time; in 1996, diplomat George Kennan and a group of distinguished foreign-policy experts; and, that same year, Brent Scowcroft, a lone authority from the administration of George H. W. Bush.

In 2018, in Because They Could: The Harvard-Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-five Years, I wrote, “No aspect looms larger in these 25 years [of US-Russia relations] than the story of NATO enlargement.”

Now that Vladimir Putin has sent the Russian army to invade Ukraine, the reasoning behind NATO enlargement has become ripe for reassessment– not now, while people are fighting, dying and fleeing, but after the carnage has ended, And then only gradually, calmly, without rancor.

Who know what drove Putin crazy enough to invade Ukraine? That’s for analysts, biographers and historians to puzzle out. Certainly apprehension over NATO expansion was part of it. So was his experience as “a boy once bullied in the back streets of Leningrad.” Meanwhile, the costs of his war are already staggering. Not just the loss of Ukrainian sovereignty. Nor Russian civil society’s forty years’ of gains since the former Soviet Union began to come apart.

The opportunities that mattered most had lain ahead. Good-faith cooperation among nations to control emission, adapt habitats and reduce solar radiation will be harder to organize than it would have been otherwise.

Even if the fondest dreams of the NATO expansionists are realized – if Russian elites and everyday citizens combine to overthrow Putin – this disastrous war makes the steadily increasing pressure on Russia’s borders seem like a hell of a risk to have run.

The problem of Taiwan is next.

Grounds for rapprochement can be found in the years ahead, but the search will require policy-makers of more sober temperament and, even then, many years will be required to restore the trust and mutual respect that has been lost.

xxx

Bill Clinton made it official in1994: NATO expansion would take place “not whether but when.” Harvard historian Tim Colton wrote in his 2008 biography of Boris Yeltsin, “A ticking time bomb had been set.” It took four more U.S. presidencies – George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden – for it to explode.

Meanwhile, Vice President Al Gore in 1993 persuaded Clinton to formally commit the nation to the Rio de Janeiro targets for greenhouse gas emissions, but conservative politicians continued to scoff.

David Warsh is a veteran columnist and an economic historian. He’s also proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

David Warsh: Is Putin responding to U.S. ‘hyper use’ of force and overreach?

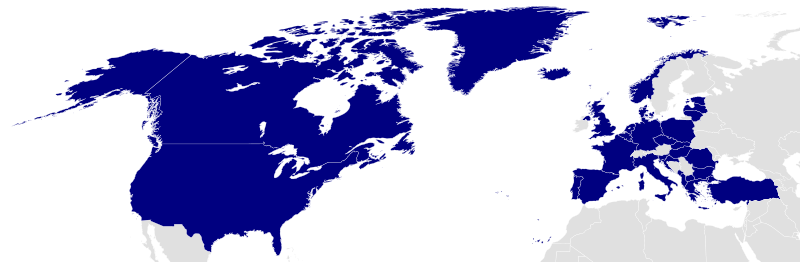

Blue indicates member states of NATO.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

With President Biden confidently forecasting a Russian “war of choice” against Ukraine –“I’m convinced he’s made the decision,” he said Feb. 18, – there is not much point in writing about it until war happens, or fails to materialize. Except to say this:

I spent some time last week leafing through books I read long ago, about an earlier “war of choice,” this one thoroughly catastrophic, as it turned – two by Robert Draper, of The New York Times, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush, and To Start a War: How the Bush Administration took America into Iraq; one by Peter Baker, also of The Times, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House; another by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, of The Washington Post, Imperial Lives in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone; and a fifth, by Michael MacDonald, of Williams College, Overreach: Delusions of Regime Change in Iraq.

My interest was piqued by a dispatch from New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski. Is NATO dealing with a crafty strategist, he asked, or a reckless paranoid? “At this moment of crescendo for the Ukraine crisis, it all comes down to what kind of leader President Vladimir V. Putin is.” He continued,

In Moscow, many analysts remain convinced that the Russian president is essentially rational, and that the risks of invading Ukraine would be so great that his huge troop buildup makes sense only as a very convincing bluff. But some also leave the door open to the idea that he has fundamentally changed amid the pandemic, a shift that may have left him more paranoid, more aggrieved and more reckless.

It seemed to me that Troianovski, and, by extension, President Biden, had neglected a third interpretation. When Putin gave a famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, criticizing the U.S. for “almost un-contained hyper use of force in international relations,” he reminded listeners in his audience mainly of the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then underway, but his subtext was NATO expansion into Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1993.

Perhaps, I thought, the way to think of Putin is as an accomplished rhetorician, creating a grand show-of-force, illustrated by satellite photographs and maps, with which to quietly bargain with various Ukrainian factions, while seeking to persuade other audiences that for three decades the behavior of the Unites States has been the neglected element, or, as the saying goes, “ the elephant in the room.” Perhaps the long table at whose far end Putin was photographed speaking with French President Emmanuel Macron was more symbolic of the distance that the Russian president feels from NATO negotiators than emblematic of his fear of COVID contagion.

Meanwhile, The Times last week published a story about a secretive U.S. missile base in Poland a hundred miles from the Russian border – a presence that seemed to give the lie to verbal assurances given long ago in negotiations over the reunification of Germany that NATO would expand not one inch to the East.

What if Joe Biden’s convictions about Putin’s intentions turn out to be no better than were those of George W. Bush about Saddam Hussein? When Russian forces finally attack Kyiv – or gradually return to their bases – we’ll know who was right and who was wrong. I’ll stop writing about it when they decide.

While we are hanging on the breathless daily news reports, though, Putin has managed to remind more than a few persons around the world of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, this time played out in in reverse. Was it really Pax Americana? Or more of a three-decade toot?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: What brought us to today's Russia; Stalin's library

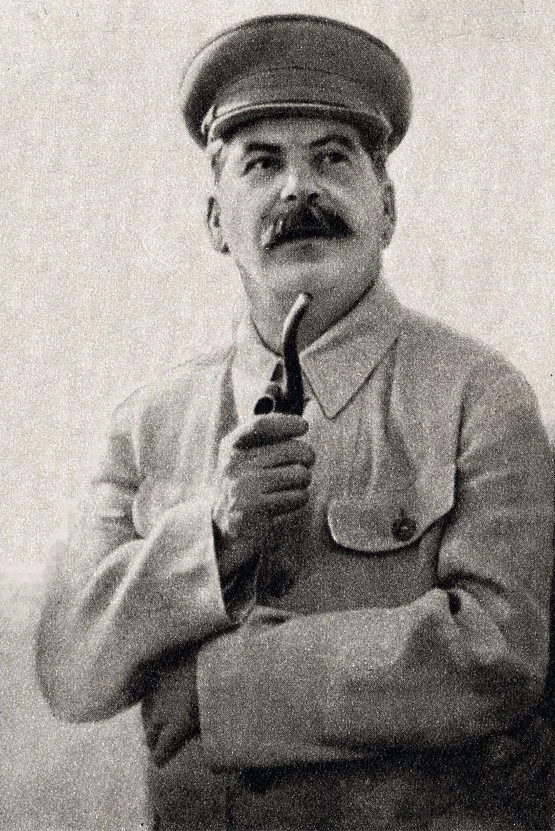

A kindly-looking Stalin — mass murderer and true believer

— 1937 Soviet propaganda photo

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a newspaperman covering the economics of transition after 1989, I became interested in the Russian experience of the ‘90s, especially after a young Russian immigrant who, having become a Harvard economics professor, took advantage of his appointment as a U.S. State Department adviser to the government of Boris Yeltsin to enter the Russian mutual-fund industry with his wife and their pals.

Since then I’ve followed the story of U.S.-Russian relations as it has gradually widened into front-page news. A friend pointed me to a fascinating book by a young philosopher about her and her family’s experience in Albania in the early ‘90s. That book, in turn, reminded me of a somewhat older account of coming-of-age as an economist in communist Hungary during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Free: A child and a country at the end of history (Norton, 2022), by Lea Ypi, a professor of political philosophy in the government of the London School of Economics, is consistently engaging, at least until its chapter on Albanian civil wars of 1997 (at which point it turns horrifying), though it offers very little interpretation of the historical Marx. This Lunch with the FT feature, by Alec Russell, describes Ypi and her views very well, but fails to tell how she pronounces her name. (It’s Ee-P, just as you would say the name of this weekly.)

The older story is By Force of Thought: Irregular memoirs of an intellectual journey, by János Kornai (MIT, 2006). Kornai died last year, at 93. For an account of his hard, heroic, ultimately distinguished career, see Klaus Nielsen’s obituary in the Guardian, or Eric Maskin’s tribute for Econometrica. More is the pity that, though often nominated, Kornai failed to be included in the Nobel pantheon; he left behind the best account that we possess of the economics of chronic shortage in centrally planned economies.

Perusing these books led in turn to Tony Barber’s review of Stalin’s Library: A dictator and his books (Yale, 2022), by historian Geoffrey Roberts. As its dictator between 1922 and 1953 (when he died), Stalin created the modern Soviet Union, killing millions of his fellow countrymen in the name of “class struggle,” while delivering victory over the Nazis at Stalingrad (previously Volgograd) in World War II, occupying half of Europe afterwards, and producing the nuclear weapons and missiles that stood off the West in a Cold War lasting forty years. It turns out that Stalin was quite the reader, possessing a personal library of 25,000 books, including more than 400 that he personally annotated. Barber writes,

Of exceptional interest are the pometki, or markings, on the books that Stalin read most closely. Using red, blue and green pencils, he scribbled expressions of disdain or disagreement: “ha ha”, “hee hee”, “gibberish”, “nonsense”, “rubbish”, “fool”, “bastards”, “scumbag”, “swine”, “liar”, “scoundrel” and “piss off”. Yet the author he read most was Vladimir Lenin, and there is not a hint of criticism in his markings on Lenin’s works — or, indeed, on those of Karl Marx.

As this suggests, Stalin was no skeptical thinker weighing up all sides of a question. He started from the premise that Marxism-Leninism had the answers. Roberts makes a convincing case that the key to understanding Stalin’s capacity for mass murder is “hidden in plain sight: the politics and ideology of ruthless class war in defense of the revolution and the pursuit of communist utopia”.

Through the tumultuous ‘80’s and the smash-and-grab ‘90’s, Russia found its way to a market economy. See Greg Ip’s well-informed appraisal of stakes the nation is facing in the current situation. Vladimir Putin is not Joseph Stalin, but he is a gambler. Keep that in mind as you read about the show-of-force bargaining now taking place over the future of Ukraine.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh: Still the Free World in a second Cold War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Since it arrived last summer, I have been reading, on and off, mostly in the evenings, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, by Louis Menand. It is a stupendous work, 18 chapters about criticism and performance, engagingly written and crammed with vivid detail. Most of it was new to me, since, while I am always interested in Thought, I don’t much follow the Arts. The book, in short, is readable, a 740- page article as from a fancy magazine. But then, Menand is a New Yorker staff writer, as well as a professor of English at Harvard University,

It is also a conundrum. The first chapter (“An Empty Sky,” is about George Kennan, a key architect of the policy of containment of the Soviet Union, its title taken from an capsule definition of realism by strategist Hans Morgenthau, in which nations after the war “meet under an empty sky from which the gods have departed”). The last chapter (”This is the End,”) is about America’s war in Vietnam (its title from the Raveonettes’ tribute to The Doors on the death of their vocalist, Jim Morrison).

In between are 16 other essays: on the post-WWII history of leftist politics, literature, jurisprudence, resistance, painting, literature, race and culture, photography, dance, popular music, consumer product design, literary criticism, new journalism and film criticism. My favorite is about how cultural anthropology displaced physical anthropology in the hands of Claude Lévi-Strauss and photographer Edward Steichen, organizer of the Museum of Modern Art’s wildly successful Family of Man exhibition in 1955

A preface begins, “This is a book about a time when the United States was actively engaged with the rest of the world,” meaning the 20 years after the end of the Second World War. Does that mean that Menand thinks the US ceased to be actively engaged with the world after 1965? The answer seems to be yes and no. When its Vietnam War finally ended, in 1975, he writes, “The United States grew wary of foreign commitments, and other countries grew wary of the United States.”

During those 20 years, says Menand, a profound rearrangement of American culture had taken place Before then, widespread skepticism existed among Americans about the place of arts and ideas in national life; respect for their government, its intentions and motives, was strong. After 1965, he finds, those attitudes were reversed. “The U.S. had lost political credibility, but it had moved from the periphery to the center of an increasing international artistic and intellectual life.” The change had come about through a policy of openness and exchange.

Artistic and philosophical choices carried implication for the way one wanted to live one’s life and for the kind of polity in which one wished to live in it. The Cold War changed the atmosphere. It raised the stakes.

Menand is right about the big picture, I think. Inarguably the U.S. grew much more free in those years, even as the governments of Russia and China cracked down on their citizens. Whether or not the lively arts were the engine – as opposed to the GI Bill, civil disobedience, the Pill, Ralph Nader, Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, the Stonewall Riots, The Whole Earth Catalog, Milton Friedman – hardly matters.

The Free World’s introduction begins with a photograph: Red Army soldiers hangs a Soviet flag from the roof of the Reichstag, overlooking the ruins of Berlin. The photo was a re-enactment, as had been that of U.S. Marines raising a flag atop Okinawa’s Mount Suribachi that had appeared in newspapers six weeks before.

But there was a difference: the Soviet photo been doctored, a second watch on the wrist of the flag-bearer needled away – unwelcome evidence, perhaps, of prior looting in the otherwise heroic scene. Cover-up was the hallmark of Russian totalitarianism, Menand seems to suggest: what the Cold War was all about.

Fast forward 30 years, to the end of the Vietnam War. The book ends with a striking peroration. Menand writes, “The political capital the nation accumulated by leading the alliance against fascism in the Second World War and helping rebuild Japan and Western Europe [the U.S.] burned through in Southeast.” The Vietnamese Communists who arrived in Saigon as the Americans left “did what totalitarian regimes do: they took over the schools and universities; they shut down the press; they pursued programs of enforced relocation’ they imprisoned, tortured, and execute their former enemies. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City and Ho’s body, like Lenin’s, was installed in a mausoleum for public viewing.”

Ahead lay another flight, this time Vietnamese citizens from their homeland. Menand continues, “Between 1975 and 1995, 839,228 Vietnamese fled the country, many on boats launched into the South China Sea [bound for Hong Kong or the Philippine Islands]. Two hundred thousands of them are estimated to have died [mostly by drowning]. Those people may or may not have known the meaning of the word ‘freedom,’ but they knew the meaning of oppression.” The English writer James Fenton, then working as a news correspondent, stayed behind to witness the aftermath of war. In the last sentence of his book, Menand quotes Fenton’s judgement: “The victory of the Vietnamese a victory for Stalinism.”

What, then, of the nearly years since the fall of Saigon, in 1975? The Chinese turn towards global markets after the death of Mao? The American resurgence as an economic hyperpower beginning in 1980? The collapse of the Soviet Union? NATO’s penning-in of Russia? The World Trade Organizations open-arms to China in 2000? The American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11? The divisions in U.S. civil society that have increased since?

The Winter Olympics in China underscore that a second Cold War has begun. What might be the consequences of it? How long will it last? How might it end? Who will turn out to be its Harry Truman? It’s George Kennan?

The distinction between a Free World and authoritarian regimes seems to hold up, though no longer do we think of the others as “totalitarian.” Britain’s reputation is diminished. Is the U.S. still leader of the Free World? Has its authority shrunk? I put Menand’s book back on the shelf thinking that it was a valuable contribution to work in progress.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, and proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

David Warsh: Putin wants to get his foes thinking

Vladimir Putin in 2018

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The first bright light on the murky situation in Ukraine shone Jan. 28, when Ukraine officials “sharply criticized” the Biden administration, according to The New York Times in its Jan. 29 edition, “for its ominous warnings of an imminent Russian attack,” saying that the U.S. was spreading unnecessary alarm.

Since those warnings have been front-page news for weeks in The Times and The Washington Post. Ukrainian President Volodynyr Zelensky implicitly rebuked the American press as well. As the lead story in The Post indignantly put it, he “ [took] aim at his most important security partners as his own military braced for a potential security attack.”

Meanwhile, Yaroslav Trofimov, The Wall Street Journal’s chief foreign-affairs correspondent, writing Jan. 27 in the paper’s news pages, identified a well-camouflaged off-ramp to the present stand-off, in the form of an agreement signed in the wake of the Russian-backed offensive in eastern Ukraine in February 2015. The so-called Minsk-2 had since remained dormant, he wrote, until recently.

Now, after a long freeze, senior Ukrainian and Russian officials are talking about implementing the Minsk-2 accords once again, with France and Germany seeing this process as a possible off-ramp that would allow Russian President Vladimir Putin a face-saving way to de-escalate.

I have had a long-standing interest in this story. In 2016, in the expectation that Hillary Clinton would be elected U.S. president, I began a small book with a view to warning about the ill consequences of the willy-nilly expansion of the NATO alliance that President Bill Clinton had begun in 1993, which was pursued, despite escalating Russian objections, by successors George W. Bush and Barack Obama. The election of Donald Trump intervened. Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years appeared in 2018.

I was relieved when Joe Biden defeated Trump, in 2020, but alarmed in 2021 when Biden installed a senior member of Mrs. Clinton’s foreign-policy team in the State Department, as undersecretary for political affairs. Seven years before, as assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, Victoria Nuland had directed U.S. policy towards Russia and Ukraine and passed out cookies to Ukrainian protestors during the anti-Russian Maidan demonstrations in February 2014. At their climax, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, a Putin ally, fled to exile in southern Russia, and, in short order, Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula.

A couple of weeks ago, I suggested that, when it came to interpreting the situation in Ukraine, it would be wise to pay attention to a more diverse medley of voices than the chorus of administration sources uncritically amplified by The Times and The Post. David Johnson, proprietor of Johnson’s Russia List, told readers he didn’t think there would be an invasion. Neither did I. Russian and Ukrainian citizens seemed to agree; according to reports in the WSJ and the Financial Times, they were going about their business normally.

Why? Presumably because most locals understood Russian maneuvers on their borders to be a show of force, intended to affect negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow.

As for what Putin may be thinking and privately saying – his strategic aims and his tactics – I pay particular attention to Harvard historian Timothy Colton. His nuanced biography of Boris Yeltsin makes him an especially interesting interpreter of the man Yeltsin in 1999 designated his successor.

Colton, a Canadian, is a member of the Valdai Discussion Club, a Moscow-based think-tank, established in 2004 and closely linked to Putin. Its annual meetings have been patterned on those of Klaus Schwab’s better-known World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland. Membership consists mainly of research scholars, East and West. A little essay by Colton surfaced 10 days ago on the club’s site, as What Does Putin’s Conservatism Seek to Conserve?

Colton observed that Putin’s personal ideas and goals, as opposed to his exercise of power as a political leader, are seldom discussed. That is not surprising, he wrote, as Putin had relatively little to say about his own convictions during his first two terms in office, aside from First Person, a book of interviews published just as he took office in 2000. That reticence diminished in his third term, Colton continued, especially now as his fourth term begins. In a speech to a Valdai conference last autumn, whose theme was “The Individual, Values, and the State,” Putin borrowed a foreign term – conservatism – and used it four times, each time with a slightly different modifier, to describe his own fundamental views. Colton wrote:

Putin noted at Valdai that he started speaking about conservativism a while back, but had doubled down on it in response not to internal Russian developments but to the fraught international situation. “Now, when the world is going through a structural crisis, reasonable conservatism as the foundation for a political course has skyrocketed in importance, precisely because of the proliferating risks and dangers and the fragility of the reality around us.”

“This conservative approach,” he stated, “is not about an ignorant traditionalism, dread of change, or a game of hold, much less about withdrawing into our own shell.” Instead, it was something positive: “It is primarily about reliance on time-tested tradition, the preservation and increase of the population, realistic assessment of oneself and others, an accurate alignment of priorities, correlation of necessity and possibility, prudent formulation of goals, and a principled rejection of extremism as a means of action.”

What of the wellsprings of Putin’s conservatism? Perhaps nothing more fundamental than the preservation of his own power. “Two decades in the Kremlin, and the prospect of years more, may incline him increasingly toward rationalizations of the status quo as principled conservatism.” An alternative explanation would emphasize life experience. The fragility that Putin was talking about at Valdai was that of the present moment, Colton wrote, but, he continued,

Putin has commented more than once on the inherent volatility of human affairs. “Often there are things that seem impossible to us,” he said in the First Person interviews, “but then all of a sudden — bang!” He gave as his illustration the event that by all accounts traumatized him more than any other — the implosion of the USSR. “That is the way it was with the Soviet Union. Who could have imagined that it would have up and collapsed? Even in your worst nightmares no one could have foretold this.” Sticking with “time-tested” formulas would suit such a temperament [Colton wrote].

What sorts of time-tested formulas might the Russian leader adopt? Colton, a player in many venues, is constrained to speak and write so carefully that it is hard for an outsider to know what with any confidence what point he was making to insiders in his recent essay. As journalist, I am not.

One time-tested formula Putin has employed frequently, to the point of habit, is a tradition I think of as having evolved in the West. This is the practice of setting out a frank public account of public-policy views. It is a rhetorical tactic set out with especial felicity by the framers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, to the effect that “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” requires those undertaking dramatic actions to declare the causes that impel them to act. In general, this Putin has done.

There was, for instance, his frank appraisal of the situation of Russia at the Turn of the Millennium, published as one of those First Person interviews in 2000. After he failed to dissuade George Bush from invading Iraq, Putin lambasted the U.S. in 2007 in a widely publicized speech to a security conference in in Munich. In 2014, after annexing Crimea, he delivered another blistering speech, this time to the both houses of the Russian parliament. And last summer, he published a long essay asserting his conviction that Ukrainians and Russians share “the same historical and spiritual space.

What might he do if his army goes home, having made its rhetorical point without firing a shot? My hunch is that he will give another speech.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

Spiridon Putin, Vladimir Putin’s paternal grandfather, a personal cook of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin

David Warsh: How America can get out of its political mess

Not much “unum’’ lately

SOMERVILLE, Mass.