SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a young magazine writer, I was a quick enough study to recognize that, in the discussion of inflation, the bourgeoning enthusiasm for monetary analysis had loaded the dice in favor of the quantity theory of money. New World treasure, paper money, central banking: it was as if monetary policy was a force independent of whatever might be happening in the economy itself. It reminded me a famous New Yorker cartoon, a patient talking to his psychoanalyst: “Gold was at $34 when my father died… it was $44 when I married my wife… now it’s $28, but I have trouble seeing.”

I wanted to suggest a variable that might represent the perspective of real analysis, though I did not yet know the term: the conviction, as I learned Joseph Schumpeter had described it, that “all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them,” and that money entered the picture as just another a technological device. Thinking about all else besides monetary innovation that was new in the world since the 15th Century, I came up with a catch-word to describe what had changed. The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking) appeared in 1984.

It certainly wasn’t theory: more in the nature of criticism, a slogan with so little connection to the discourse of economics since Adam Smith that it didn’t bother specifying complexity of what. But the word had an undeniable appeal. “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

Sure enough: Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, appeared in 1987; Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos and Order, by M. Mitchel Waldrop; and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, by Roger Lewin, followed in 1992; and in the next decade, a whole shelf of books appeared, of which The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Remaking of Economics, by Eric Beinhocker, in 2006, was probably the most interesting.

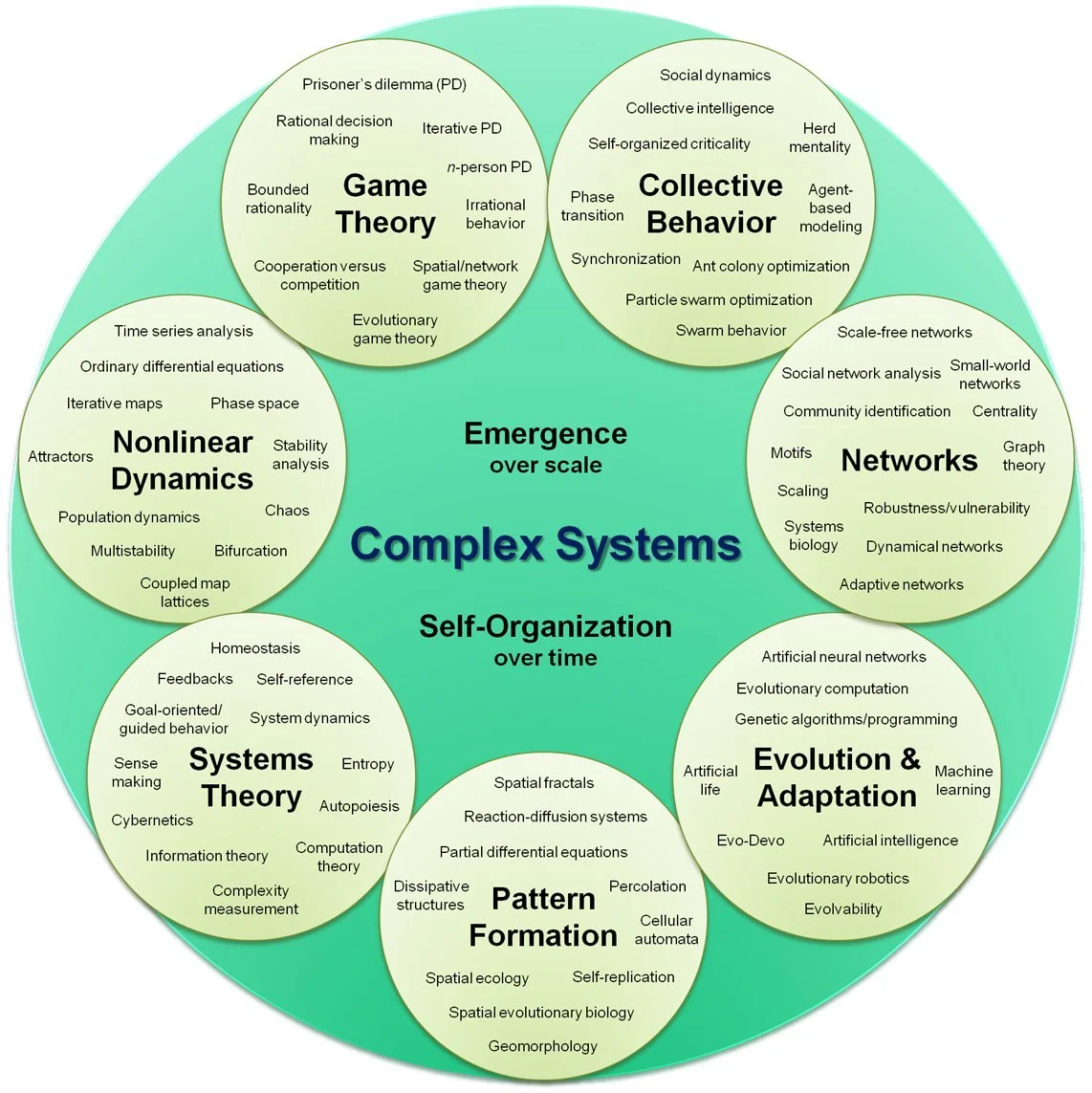

Organizational map of complex systems broken into seven sub-groups.

— Hiroki Sayama, D.Sc

But the question remained: complexity of what? The long quote-box on the back of the book jacket had put it this way:

To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupation dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques, such a graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of our subject are not our subject here, however. It is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what make the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.

Fair enough, for purposes of journalism. There was however something missing in my discussion: to wit, any real knowledge of structure of technical economic thought. I had come across the economist Allyn Young (1876-1929) in my reading, a little-remembered contemporary of Irving Fisher, Wesley Clair Mitchel and Thorstein Veblen, Schumpeter, and John Maynard Keynes. I classified him, with Schumpeter, as a “supply-sider,” in keeping with the controversies of the early ‘80’s, “locating in the businessman’s entrepreneurial search for markets the most profound impulse toward economic growth.” I added only that “We are coming at it from a slightly different direction is this book.”

It wasn’t until I re-read “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” (for those who have access to JSTOR), in the Economic Journal of December 1928, that it dawned on me that it was complexity of the division of labor that I had been thinking about. A particular passage towards the end of Young’s paper brought it home.

The successors of the early printers, it has often been observed, are not only the printers of today, with their own specialized establishments, but also the producers of wood pulp, of various kinds of paper, of inks and their different ingredients, of type-metal and of type, the group of industries concerned with the technical parts of the producing of illustrations, and the manufacturers of specialized tools and machines for use in printing and in these various auxiliary industries. The list could be extended, both by enumerating other industries which are directly ancillary to the present printing trades and by going back to industries which, while supplying the industries which supply the printing trades, also supply other industries, concerned with preliminary stages in the making of final products other than printed books and newspapers. I do not think that the printing trades are an exceptional instance, but I shall not give other examples, for I do not want this paper to be too much like a primer of descriptive economics or an index to the reports of a census of production. It is sufficiently obvious, anyhow, that over a large part of the field of industry an increasingly intricate nexus of specialized undertakings has inserted itself between the producer of raw materials and the consumer of the final product.

Young, a University of Wisconsin PhD, had taught both Edward Chamberlin and Frank Knight as a Harvard professor, before accepting an offer from the London School of Economics to chair its department, at a time when LSE was looking to further distinguish itself. It was as president of Section F of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he delivered his paper on increasing returns. Then, on the verge of returning to Harvard, he died at in an influenza epidemic. He was 52.

By the time that I re-read Young’s paper, I had met Paul Romer, a young mathematical economist then at the University of California Berkley, who had been working for years on more or less exactly the same questions that Allyn Young had raised in literary fashion fifty years before. Romer introduced me to the distinction economists made between “endogenous” and “exogenous” factors.

Endogenous were developments within the economic system; exogenous were those apparently outside, to be “bracketed” or put aside as matters the existing system hadn’t yet found ways to satisfactorily explain. Only a few years earlier, Robert Solow, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for, among other things, his finding that as much of 80 percent of economic growth in a certain period couldn’t be explained by additional increments of labor and capital. Whatever it was, it was to be expressed as a “Residual,” exogenous to the system of supply and demand.

First in “Growth Based on Increasing Return Due to Specialization,” in 1987, then in “Endogenous Technical Change,” in 1990, Romer solved the problem, employing new mathematics he had acquired to describe it. The magic of the Residual, it turned out, was human knowledge, a non-rival good in that, unlike land, labor, or capital, it could be possessed by any number of persons at the same time. I wrote a book about what had happened; Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton) appeared in 2006. In 2018, Romer, by then at New York University, and William Nordhaus, of Yale University, shared a Nobel Memorial Prize for their work on the interplay of technological development and climate change.

I had been hit by the meatball. I understood why Early Hamilton and John Neff had so little to say to each other, why Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson didn’t agree: they were men searching under streetlights for answers – different streetlights, separated by areas of darkness that had yet to be illuminated. I understood that economists could be trusted to continue to develop their field,

But there were still plenty of questions to be answered, including the one that had bothered me since the beginning. Why do we call rising prices “inflation?”

xxx

One of the joys of writing about the news is that you ordinarily never know where you’re going from one week to the next – reading as well, I expect. Yet from small beginnings last autumn, I have launched a mini-series about some things I have learned since publishing The Idea of Economic Complexity in 1984. Had I known at the beginning what to expect, I would have announced a series, Complexity Revisited. I do so now.

This week is the fourth installment, counting the first piece – about the 700-year wage and price index of Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – that triggered the rest. There will be four more, eight in all. Each piece subsequent to the first is connected to something I discovered later, in the witings of Joseph Schumpeter, Charles Kindleberger, Allyn Young, Steven Shapin and Simon Schafer, Nicholas Kaldor, Hendrik Houthakker, and Thomas Stapleford.

What’s the point? It all has to do with the nature of money – how we control it, how it is accumulated, saved and disbursed. Banking is already thoroughly digitized; the digitalization of money itself looms in the future. It makes sense to go back to first principles. These have to do with central banking, it turns out, perhaps the least understood of major modern institutions of governance.

The need here to think matters through, at least a little, arose in connection with other projects underway, large and small. I don’t apologize for having undertaken the series. I’ve done it twice before over the years, each time with good results. But there is something about the weekly column that wants to stay close to the news, especially in these turbulent times. I can confidently promise not to do it again. Back to the news next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

— Photo by Acabashi