Your eyes will get used to it

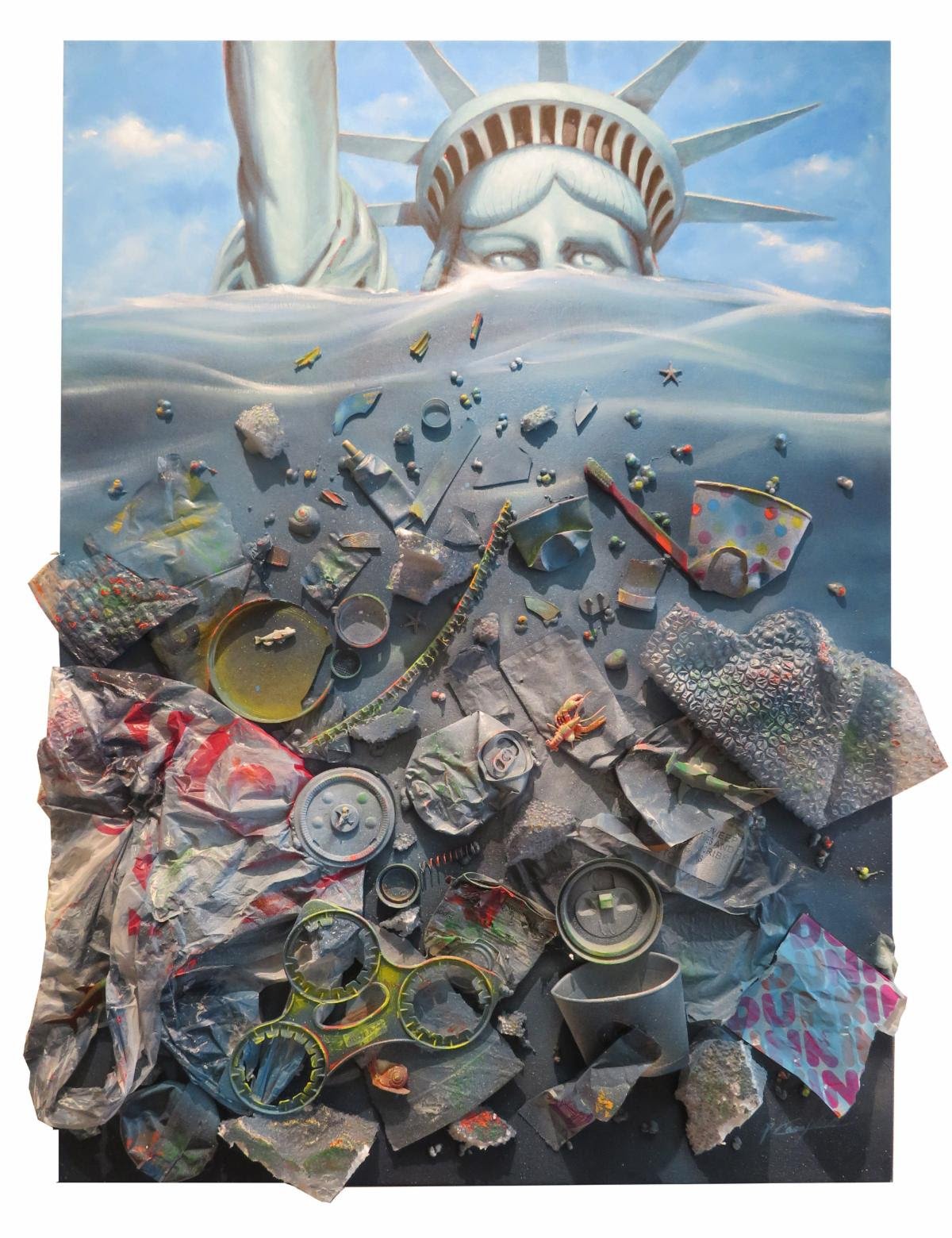

“August” (oil), in “Ocean Views II,’’ by Nick Paciorek, at the Feinstein Gallery at the University of Rhode Island’s Providence campus. He’s based at the Pitcher-Goff House art center, in Pawtucket, R.I.

Some detritus of commercial civilization

Painting by Lincoln, R.I.-based artist Peter Campbell in his show through June 24 at Gallery 175, Pawtucket, R.I.

The Eleazar Arnold House (built in 1693), in Lincoln, R.I., is a rare surviving example of a stone-ender, a once-common building type in New England featuring a massive chimney end wall. The houses stone work reflects the origins and skills of settlers who emigrated to New England from southwest England, and it’s a National Historic Landmark.

Leave him up

William Blackstone in glorious stainless steel in Pawtucket, R.I.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The bookish William Blackstone (1595-1675) (also called Blaxton) was an Anglican minister who might have been the first permanent white resident of what is now Rhode Island, moving down from Boston and settling in today’s Lonsdale section of Cumberland in 1635, the year before Roger Williams founded Providence. The Blackstone River and a bunch of other things around here are named for him.

In the future Cumberland, on the east bank of the river that would bear his name, the reclusive and apparently kindly and tolerant intellectual read, wrote, tended cattle, planted gardens, and cultivated an apple orchard; he came up with the first variety of American apples, the Yellow Sweeting. He called his home "Study Hill," and it was said to have the largest library in the English colonies at the time. Sadly, his library and house were burned down in 1675 during King Philip's War, the very bloody and destructive conflict between Native Americans and English colonists that lasted from 1675 to 1678 and changed the course of American history. Blackstone died in 1675, just before the outbreak of the conflict.

Consider that his friends included the Narragansett tribe chiefs Miantonomi and Canonchet and the Wampanoags’ Massasoit and Metacomet. Metacomet is also known as King Philip (to mark the friendly relations his father, Massasoit, had with the English), whose followers were the ones who destroyed Blackstone’s home.

But now some Narragansetts want a new stainless-steel sculpture of Blackstone at the corner of Roosevelt and Exchange streets in Pawtucket taken down. They’re trying to make him into some sort of symbol of the brutal white takeover of their lands and the vast suffering and death of Native Americans that accompanied the English colonialization of what the English named New England. But Blackstone is a pretty inaccurate example of white aggression!

It’s appropriate that his statue remain up, given his importance to the history of the region. It’s not as if this is a statue of the likes of the cruel slaveowner, and traitor, Robert E. Lee. Such works are best kept in museums. (There are no statues of Hitler in outdoor parks in Germany, despite his historical importance.)

And, yes, you could say that George Washington was a traitor to Britain and he owned slaves. But unlike Lee, he didn’t take up arms against “his country” to ally himself with a “country’’ whose central mission in its rebellion against the United States was the preservation and indeed expansion of slavery. And Washington, whose slaves were freed at his death under his will, also was not considered a cruel slaveowner.

Anyway, why not see if a statue of a Native American chief from Blackstone’s time in Rhode Island could be commissioned to be put up near Blackstone’s? It would be culturally healthy if we had a wider range of historical figures represented by our public statues.

Here’s a nice crisp biography from the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame:

http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=45

Find safer places for homeless

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Tent cities” of homeless people are all over the place. A particularly noticeable one was the camp just closed down in Pawtucket on the west bank of the Seekonk River to make way for a soccer-stadium project, which might actually get built.

Many, probably most, of the people at this camp are mentally ill. In these places they might find kindred spirits but they also face such dangers as exposure to the elements, assaults and thefts. And the atmosphere is conducive to alcohol and drug abuse.

These tent cities have been common since the de-institutionalization movement that got going in the late ‘60s, when officials hoped that new psychotropic medications would allow many of the mentally ill to be released from state mental hospitals, saving taxpayers money. But for many mentally ill people this didn’t work out because they didn’t like the side-effects of these meds for such illnesses as schizophrenia and manic-depression (aka bi-polar disease). For that matter, some of these people like feeling “crazy.’’

Or some have not been given adequate guidance on how to use the meds or don’t have a way to pay for them or can’t get to pharmacies to get them.

I think that we need more mental hospitals for long-term care. As for those people, mentally ill or not, who actually prefer to live in settings like tent cities, the states and localities should consider setting aside permanent places for them on public land, or rent space from private landowners, where the “campers’’ could be better monitored by police, social workers and public-health agencies. Moveable tent cities pose too many dangers. And be they temporary or permanent, they should not be near regular residential or commercial areas; they are too disruptive.

Folks seeking help with serious mental-health and/or substance-abuse problems might want to look at this Rhode Island state Web site to find available spaces at institutions.

William Morgan: A haunted grandstand in Pawtucket

The stands of what had been Narragansett Park

— Photo by William Morgan

Just off the unspeakably grim Newport Avenue strip, in Pawtucket, R.I., an abandoned colossus reminds us of once glorious days of thoroughbred horse racing patronized by swells from Newport and New York. This enormous structure was once part of a 200-acre complex with barns that housed 1,000 horses.

Narragansett Park opened in 1934, after the state’s official airport was declared to be Hillsgrove Airfield (now T.F. Green Airport), in Warwick, instead of Pawtucket’s What Cheer Airport, and pari-mutuel betting was reinstated after a 30-year ban; it folded in 1978 after a disastrous fire that killed three-dozen horses. The grandstand then became Building #19, the odd-lots warehouse, or "America's laziest and messiest department store," as its founder Gerry Elovitz dubbed it.

The slide from society amusement (thoroughbreds such as Whirlaway and Seabiscuit raced here on its mile-long oval), and a "Retail Derby" against the big-box stores, to inevitable decay, reverberates with the last days of our totally corrupt, would-be Nero-style emperor. Reminding us of Rome's Circus Maximus, home of the great chariot races, Narragansett Park's haunted grandstand is apt metaphor for the end of 2020.

William Morgan is a writer, architectural historian and photographer based in Providence. He has written on stock-car racing for The New York Times. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Postcard photo of Narragansett Park in the 1950s

Frank Carini: The partial recovery of the Seekonk River

Looking out at the Henderson Bridge over the Seekonk from Providence’s Blackstone Park

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When driveways, highways, rooftops, patios and parking lots cover 10 percent of a watershed’s surface, bad things begin to happen. For one, stormwater-runoff pollution and flooding increase.

When impervious surface coverage surpasses 25 percent, water-quality impacts can be so severe that it may not be possible to restore water quality to preexisting conditions.

This where the Seekonk River’s resurgence runs into a proverbial dam. Impervious-surface coverage in the Seekonk River’s watershed is estimated at 56 percent. It’s tough to come back from that amount of development, but the the urban river is working on it, thanks to the efforts of its many friends.

The Seekonk River, from its natural falls at the Slater Mill Dam on Main Street in Pawtucket, R.I., flows about 5 miles south between the cities of Providence and East Providence before emptying into Providence Harbor at India Point. The river is the most northerly point of Narragansett Bay tidewater. It flows into the Providence River, which flows into Narragansett Bay.

While it continues to be a mainstay on the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s list of impaired waters, the Seekonk River is coming back to life.

“I started rowing at the NBC [Narragansett Boat Club] 10 years ago when I realized that I was on the shores really of a 5-mile-long wonderful playground,” Providence resident Timmons Roberts said. “I just think it’s a magical place, and seeing the river come back to life has meant a lot to me.”

The Narragansett Boat Club, which has been situated along the Seekonk River since 1838, recently held an online public discussion about the river’s recovery.

Jamie Reavis, the organization’s volunteer president, noted the efforts that have been made by the Blackstone Parks Conservancy, Fox Point Neighborhood Association, Friends of India Point Park, Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, Providence Stormwater Innovation Center, Save The Bay, and Seekonk Riverbank Revitalization Alliance, among others, to restore the beleaguered river.

“Having rowed on the river for over 30 years now, I can attest to their efforts,” Reavis said. “It was practically a dead river. It almost glowed in the dark back in the day. It is now teaming with life. Earlier this summer, a bald eagle flew less than 10 feet off the stern of my single with a fish in its talons. Watching it fly across the river and up into the trees is a sight I will not soon forget, nor is it one I could have imagined witnessing 30 years ago.”

Decades of pollution had left the Seekonk River a watery wasteland.

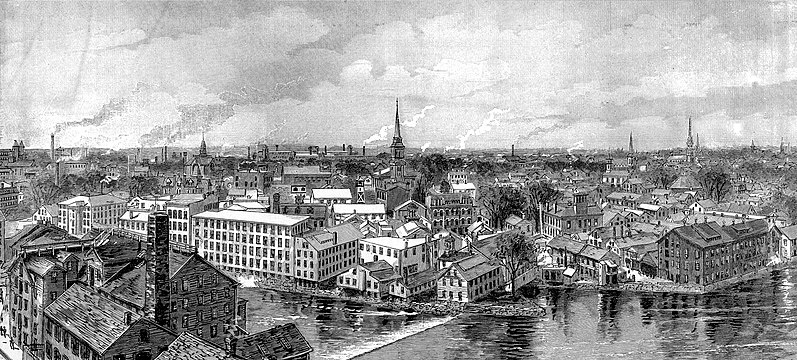

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries some of the first textile mills in Rhode Island were built along the Seekonk River. The river, and one of its tributaries, the Blackstone River, powered much of the early Industrial Revolution. Mills that produced jewelry and silverware and processes that included metal smelting and the incineration of effluent and fuel left the Seekonk and Blackstone rivers polluted.

There are no longer heavy metals present in the water column of the Seekonk River, but sediment in the river contains heavy metals, including mercury and lead.

Swimming in the Seekonk River, which doesn’t have any licensed beaches, and eating fish caught in it aren’t recommended because of this toxic legacy and because of the continued, although declining, presence of pathogens, such as fecal coliform and enterococci. The state advises those who recreate on the river to wash after they have been in contact with the water. It also advises people not to ingest the water.

But, as both Roberts and Reavis noted, the Seekonk River is again rich with life and activity. River herring, eels, osprey, cormorants, gulls and the occasional seal and bald eagle can be found in and around the river. The same can be said of kayakers, fishermen, scullers, and birdwatchers.

The river’s ongoing recovery, however, is threatened by rising temperatures, sewage nutrients and runoff from roads, lawns, parking lots, and golf courses in two states that dump gasoline, grease, oil, fertilizer, and pesticides into the long-abused waterway.

The Sept. 30 discussion was led by Sue Kiernan, deputy administrator in the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Office of Water Resources. She has spent nearly four decades, first with Save The Bay and the past 33 years with DEM, working to protect upper Narragansett Bay.

She spoke about how water quality in upper Narragansett Bay, including the Seekonk River, has improved through efforts both large and small, from the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow (CSO) abatement project to wastewater treatment plants reducing the amount of contaminants being dumped into the waters of the upper bay to brownfield remediation projects to the many volunteer efforts, such as the installation of rain gardens and the planting of trees, conducted by the organizations that sponsored her presentation.

She noted that nitrogen loads, primarily from fertilizers spread on lawns and golf courses, that are washed into the river when it rains, lead to hypoxia — low-oxygen conditions — and fish kills. Since 2018, six reported fish kills that combined killed thousands of Atlantic menhaden have been documented by DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries in the Seekonk River.

Kiernan said excessive nutrients, such as nitrogen, stimulate the growth of algae, which starts a chain of events detrimental to a healthy water body. Algae prevent the penetration of sunlight, so seagrasses and animals dependent upon this vegetation leave the area or die. And as algae decay, it robs the water of oxygen, and fish and shellfish die, replaced by species, often invasive, that tolerate pollution.

While these nutrient-charged events remain a problem, she said, the overall habitat of the Seekonk River is improving. Kiernan noted that in recent years some 20 species of fish, including bluefish, black sea bass, striped bass, scup, and tautog, have been documented in the river.

The Seekonk River is still a stressed system, but Kiernan said the river is seeing a positive trend in its recovery.

“We’re not in a position to suggest that its been fully restored, and honestly I don’t think that we’ll be in a position to do that until we get the CSO abatement program further implemented,” she said. “But I think you can take some satisfaction in knowing that there are days where things look OK out there.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

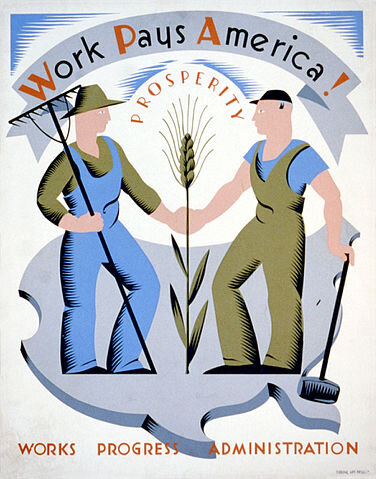

Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Betting on soccer's future

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s important to remember that Fortuitous Partners’ plan to build a soccer stadium as a key part of a $400 million mixed-use project is not necessarily based on the current audience for soccer in southeastern New England as much as where it might be in five or ten years. While Major League Baseball’s audience has been slipping, professional soccer is clearly growing, and various factors, including the love of soccer in various national and ethnic groups, make this growth likely to continue or even accelerate. It is, after all, the leading world sport.

xxx

The Worcester Business Journal reports that more that over half of that city’s renters want to move to another city. Quoting Renter Migration Report, it cited Boston, at 43 percent, as the top destination for Worcester refugees. Providence – embarrassingly? -- came in a very distant second, at 4.3 percent, and the old mill town of Norwich, Conn., at 4.2 percent. Ah, the magnetism of New England’s only world city! But maybe the WooSox will hold back a few of these dissatisfied residents.

A new Pawtucket?

Rendering of the Fortuitous Partners proposal for Pawtucket

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

t’s far too early to know the fate of a Fortuitous Partners proposal to create a $400 million project in downtown Pawtucket that would include a minor league soccer stadium, an “indoor sports event center,’’ apartments, a hotel, offices, shops and restaurants. What will the financing environment look like over the next few years? What if the nation goes into a recession soon? But from what we know now it does look like a better -- and of course much bigger -- project for the city and region than the Pawtucket Red Sox plan to build a new stadium – as sad as the team’s exit is.

The project would leverage people’s love of being along the water – in this case the Seekonk River (which I always think is the Blackstone in that part of Pawtucket) – and presumably heavily promote the project to people from very expensive Greater Boston who might want to live in Pawtucket, further encouraged to do so by the Pawtucket-Central Falls MBTA commuter rail station, scheduled to open in 2022. A big question is how successful the soccer stadium would be, however popular the greatest international sport has become around here, considering that the major league New England Revolution is based just up the road at Gillette Stadium, in Foxboro.

The public part of the financing totals $70 million to $90 million, most of it from a commonly used tax technique called “tax increment financing.’’ This lets developers use part of the tax revenue created by developments to help pay to build them. Also involved in what the developers call “Tidewater Landing’’ are often controversial federal “Opportunity Zone’’ tax breaks that are supposed to encourage economic development in low-income areas but, many note, greatly benefit rich developers. But then, most tax breaks favor the rich. (See below.)

In any case, I hope that this is not one of those projects whose fate is tied in knots in layer upon layer of regulatory red tape. America used to be known for doing big projects; now, big – and needed— projects often seem impossible because of the veto power of too many interest groups, public and private. And there is no such thing as a perfect project. For an overview of our big-project paralysis, using New York’s Penn Station as Exhibit A, please hit this link.

Pawtucket's nonstop crisis

Very prosperous but very polluted Pawtucket in 1886, viewed from the steeple of the Pawtucket Congregational Church. Just don’t think about the child labor.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘Having lost the PawSox and Memorial Hospital, Pawtucket officials are desperate to keep Hasbro’s headquarters. But the toy and game company, while expressing empathy, will solely make its decision based on bottom-line considerations and its projection of company needs and wants over the next decade. That might mean moving to downtown Providence, close to the designers at the Rhode Island School of Design, other colleges and many other activities and services lacking in Pawtucket -- and far less car-dependent.

Or perhaps it might make the most sense for Hasbro to move to Los Angeles or New York, two capitals of the entertainment industry, of which Hasbro is very much a part.

Good luck to Worcester!

Proposed stadium for the Worcester Red Sox.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

I was driving through Pawtucket the other day over its Third World roads and by its decayed-looking public schools. That made me wonder again why the State of Rhode Island and Pawtucket would have wanted to enter into a massive public-borrowing scheme to build a publicly owned stadium that would benefit some very rich businessmen in a sport that seems to be in long-term decline. Instead, why not borrow for such far more important things as transportation infrastructure? What indeed is the opportunity cost in all this?

Wouldn’t the old mill town of Pawtucket improve its economy a lot more by fixing infrastructure to be used by a very wide variety of people? Barely paved roads are not exactly an advertisement to lure companies, nor are crumbling schools.

And if a baseball stadium is such a great economic-development energizer (which it isn’t) how come, even after some expensive McCoy Stadium upgrades over the years, the neighborhood around McCoy still looks like, well, the neighborhood around McCoy?

The whole PawSox thing, in Rhode Island and now in Worcester, bespeaks a sort of bread-and-circuses approach, in which appeals to romanticism – in this case baseball fans’ --- trump economic reality. For that matter, what percentage of the population of Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts actually go to PawSox games?

Meanwhile, there’s starting to be some buyers’ remorse in Worcester about the very generous offer to lure the PawSox that was secretly (and no wonder!) negotiated over the last few months by the city, the state and the PawSox owners. The deal includes more than $100 million in city borrowing, not including interest. Some of this is supposed to be repaid by a mix of hoped-for taxes and fees in a new development district around the stadium. Will all that development happen? I doubt it. Note that interest rates are rising and that history suggests that a recession – perhaps a deep one – will start in the next couple of years. The taxpayers’ stadium is supposed to open in 2021.

Robert Baumann, an economist at the College of the Holy Cross (conveniently situated in Worcester) and a nationally known expert on the economics of publicly financed stadiums, gave a hearty thumb’s down to the Worcester deal. Among his remarks in a Worcester Telegram article:

“The summary of {the} research is simple: public money towards stadium construction is rarely, if ever, worth the investment….”

“{The} improvement and increased spending in one neighborhood usually comes at the expense of the rest of the area. … In essence, new stadiums typically trade off concentrated gains in the immediate area with diffuse losses everywhere else.’’

“According to Minor League Baseball, per game attendance at International League games this year is currently about 4.9 percent lower compared to last year and 7.9 percent lower compared to ten years ago. …Usually new stadiums come with a ‘honeymoon’ period of about three years where attendance spikes above its long-run trend…. {W}hat happens after the honeymoon is over?’’

“Simply put, this ownership group has the money {to build a stadium with its own wealth} but pitted two nearby municipalities against each other in order to get the best deal. Given that same public money also funds teachers, cops, and firefighters, this doesn’t strike me as an ownership group that cares much about Worcester or Pawtucket.’’

"The idea that this is going to serve as a catalyst for economic development, which is the hope – and I emphasize the word hope – is misguided," Robert Baade, an economist at Lake Forest College, in Illinois, told the Worcester Business Journal. John Solow, a Massachusetts native and an economist at the University of Iowa, told the publication, "There's a great deal of consensus among sports economists of all political stripes that this is not a good thing for local governments to be doing,"

But they may well do it anyway in Worcester because of the romanticism of the small percentage of the population who actually go to Minor League games and that old wishful suspension of disbelief. If it happens, it will be a wealth transfer from the middle class to the rich. But it will raise the spirits of local baseball fans, if not necessarily most football, hockey, soccer or tennis fans. Money isn’t everything! The owners are, well, hard-working capitalists seeking to maximize their profit by cultivating the romanticism of their fans and the politicians who seek their support.

Rhode Island Public Radio has a useful discussion on the pros and cons of publicly financed baseball stadiums. To read and hear it, please hit this link.

http://www.ripr.org/post/other-cities-stadium-woes-serve-warning-worcester-and-pawsox

When the ER is your primary-care doctor

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Memorial Hospital, in the old mill town of Pawtucket, R.I., may have been too uneconomic to remain open as a full community hospital but state officials and others could have done a better job anticipating that closing Memorial, with its disproportionately sick and low-income clientele, would overwhelm the emergency rooms of the Miriam Hospital and Rhode Island Hospital. One reason is that America has about the most fragmented (and expensive) health-care “system’’ in the Developed World, which leads all too many patients – especially low-income ones -- to use hospital emergency rooms as their main source of health care. That’s a notably inefficient and expensive way of getting care!

Presumably the proliferation of free-standing emergency departments and drugstore-chain clinics will eventually reduce the severe crowding in hospital emergency rooms in coming years. So would public-education campaigns to discourage people from using hospital ERs for such routine ailments as pink eye and bad colds

Hotels as economic indicators?

Providence's grand Biltmore Hotel, built in 1922.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

For some reason, news of the recent proliferation of hotel projects in Providence recalled to me the late film mogul Sir Alexander Korda’s remark that you should “always go to the best hotel…{because} sooner or later someone will appear who will give you money.’’

At last count, there were a total of eight hotels being built or planned in Providence. I have to think that this suggests that there’s more business confidence in the future of the city and Rhode Island than most citizens think. Hotels, after all, cater to businesspeople and tourists.

Presumably the hotel developers believe that there will be more economic activity in the city in the next few years. It’s hard to figure out how much of this is due to the Raimondo administration’s relentless courting of companies to get them to move to Providence, how much to firms’ interpretation of general national and regional business cycles and how much to Providence’s proximity to booming Greater Boston.

The new hotels will boost the city in some rather indirect ways. Hotels, especially their lobbies, function rooms and restaurants, are natural meeting places for businesses. Thus they make cities more dynamic for deal-making. Airbnbs and bed and breakfasts don’t quite do that.

Some old hospitals can be turned into very nice hotels, as a recent Washington Post article reported. Many more hospitals are likely to close as outpatient institutions and home care provide services, even acute-care services, that used to be only available in hospitals, and as new pharmaceuticals and medical devices make it easier to avoid hospitalization. To read The Washington Post article, please hit this link:

As I’ve written before, Pawtucket’s Memorial Hospital’s attractive and very solid buildings could be turned into a large assisted living center, condos, apartments or even, yes, a hotel.

Too many hospitals

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Care New England’s decision to close Memorial Hospital, in Pawtucket, or at least its inpatient services and emergency room, didn't surprise me at all. The fact is that Memorial’s days as a full-scale community hospital have long been numbered.

Our region has too many hospitals in a time when highly effective medications for such chronic ailments as heart disease, as well as proliferating outpatient facilities, such as comprehensive and specialty physician group practices, urgent-care centers, drugstore clinics and free-standing emergency departments, treat many of the ills that used to be treated only within hospitals. Just consider the number of surgeries now done outside hospitals, and that patients are discharged from hospitals after surgery there much faster these days. What might have kept them in a hospital for a week or two a couple of decades ago might now only keep them there for a couple of days.

And for the really serious and/or complicated stuff, patients can go to Rhode Island Hospital or the Miriam Hospital (the latter very close to Memorial), both in Providence, or to a hospital in the world-renowned health-care complex in Greater Boston (of which the Providence area is gradually becoming a part).

Only a small percentage of Memorial’s almost 300 beds are occupied and the place’s operating losses continue to swell.

So what will become of the facility? Probably much outpatient treatment and testing will continue in parts of the hospital buildings; after all, lots of physicians’ offices and very expensive equipment are there. (I go to see my cardiologist at Memorial every few months.) The rest of the structures might be turned into apartments, condos, offices, coffee shops, bars and so on – rather like a mill conversion.

The controversy about Memorial is really more about the threat to the hundreds of jobs at the hospital and the associated politics than about health care. But given the aging of the population, among other factors, the need for physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, health-care aides and others in the sector will only grow; most of the laid-off folks at Memorial should fairly swiftly find new positions. But many will find leaving the hospital wrenching even as they find jobs elsewhere in the region that might be better for them in the long run. It’s a community.

Of course, politicians will denounce the closing even as they fail to come up with plausible arguments for keeping this old community hospital open in a time of revolutionary change (and confusion) in health care. And it’s been a very long time since Pawtucket was the sort of thriving factory town that could easily support such institutions as hospitals.

Now the city ever more desperately seeks the state’s help to finance a stadium for the Pawtucket Red Sox, although most Rhode Islanders oppose such help, according to a poll done for GoLocal by Socialsphere -- founded by John Della Volpe, the director of polling at the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics at Harvard.

Far more promising is the coming Pawtucket/Central Falls train station. This facility will, among other benefits, help those cities become Boston suburbs for those who can’t afford the very steep housing costs in and around “The Hub’’ and maybe get some back-office work from Greater Boston companies in mills and other old buildings that have so far escaped the arsonists. Maybe some will live in what is now Memorial Hospital.

If Mass. won't help pay to build baseball stadium....

McCoy Stadium, the current home of the Pawtucket Red Sox.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Those who think that Worcester is about to grab the Pawtucket Red Sox should consider this news from the (Worcester) Telegram & Gazette.

Hit this link: http://www.telegram.com/news/20170813/worcester-city-councilors-love-idea-of-wooing-pawsox-but-obstacles-loom from the (Worcester) Telegram & Gazette:

“Massachusetts legislators told the Telegram & Gazette …{that} the {state} Legislature is unlikely to put public dollars toward a stadium for a private team. And even if a deal in Rhode Island that seeks to do that falls through, and neither city offers public money, staying in Pawtucket would likely be the shrewder move,’’ a stadium expert told the paper.

“All things being equal, Worcester is probably going to have to pay a higher subsidy to get them,” said Victor A. Matheson, a College of the Holy Cross economics professor who specializes in stadiums. After all, the Worcester Metropolitan Statistical Area is only about half the size of the Providence-Warwick Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes Pawtucket. (Also, Worcester is not on the Main Street of the East Coast -- Route 95. Pawtucket is.)

“It sounds wonderful, doesn’t it?” Senate Majority Leader Harriette L. Chandler (D.-Worcester) said of the idea of the PawSox moving to Worcester. ”(But) who’s going to pay for it?”

“The reality,’’ she told the paper, “is that the Legislature has an established precedent of not putting public money into sports stadiums.’’ And Massachusetts is of course a much richer state than Rhode Island on a per-capital basis.

While Massachusetts has spent money for public-infrastructure improvements associated with stadiums (most notably around Gillette Stadium, in Foxboro), that’s not the same as the millions that the PawSox wants from Rhode Island taxpayers to actually build a new PawSox stadium itself in downtown Pawtucket. The Boston Red Sox, by the way, got no public money for its massive improvements at Fenway Park in recent years.

The PawSox want $38 million in public money in Rhode Island to build a new stadium: $23 million from the state and $15 million from Pawtucket. The PawSox assert that the long-term loans from the public for the project would be repaid from the tax revenues that the new stadium generated and so wouldn’t hurt taxpayers. But of course it’s impossible to know how well the team and stadium would do in coming decades, indeed how popular baseball in general will be.

Anyway, I continue to be very skeptical that the PawSox would go to Worcester. And I hope that they’ll stay in Pawtucket. Had a wonderful evening there a couple of weeks ago.

Revolutionary move to Pawtucket?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' in GoLocal24.com

A group of us were talking the other day about the Pawtucket (R.I.) Red Sox’s plan for a multi-recreational-use downtown “Park of Pawtucket’’ at and around a successor stadium of McCoy Stadium. The PawSox organization says it would provide “recreation, entertainment and other amenities year-round,’’ including “concerts, hockey and certain family attractions.’’ Soundsnice, but it’s still hard to see how well this would work without a covered stadium, considering that annual cold snap called “winter’’. The “Park of Pawtucket’’ concept is obviously part of the pitch to get state money to help pay for a McCoy replacement.

Meanwhile, the CEO of GoLocal, Josh Fenton, suggested (in jest?) that the New England Revolution move its base to this new stadium from Gillette Stadium, in Foxboro. Unlike at Gillette, it might often have a chance of filling the stands at a new facility to be shared with the PawSox. Rhode Island, in part because of its large Hispanic and Asian community, loves soccer. And such a move would pull deep-pocketed Robert Kraft, the owner of the Revolution and the New England Patriots, into Rhode Island.

I wonder if the biggest sport in most of the world -- soccer (or "football'' as it's usually called in English-English) -- will ever reach the popularity of that more brutal (brain damage, anyone?) game we call "football'' in the U.S.

Salt thicker than snow.

Is it really necessary to put salt on the roads that's thicker than the snow it is supposed to melt? That's what they do in Pawtucket, R.I., which must be a triumph for the cause of water pollution and vegetation killing. And what a waste.

Frank Carini: Good news about reusing old places

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRINews, whence this piece originated The Industrial Revolution left many New England cities and towns with a legacy: manufacturing pollution that turned once-productive, and often pristine, land and water into dumps. This practice of contaminating natural resources and then leaving behind scarred remains, after the offending business went bankrupt or left for greener pastures, continued well into the 20th century.

The result: By the end of the 1980s, thousands of brownfields dotted the southern New England landscape, especially in its core urban areas. Remediating brownfields is a constant battle that pits public health and environmental concerns against cost factors. Clean-up efforts are often interrupted by hidden obstacles, such as underground storage tanks filled with waste oil, and finding the responsible party to pay the price is virtually impossible.

A brownfield, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is an abandoned or underutilized industrial/commercial facility where redevelopment is complicated by real or perceived environmental contamination. And these derelict and damaged properties represent do-overs — at least that’s how the EPA sees it.

“We view these sites as opportunities,” said Frank Gardner, EPA brownfields coordinator for Region 1. “Every brownfield site is an opportunity. We provide funding to actively clean up these properties, to make them safer for the public and for economic development."

In the past few years, southern New England has been the beneficiary of considerable EPA funding to help remediate brownfields. In fiscal 2014, for example, the EPA distributed a total of $67 million to all 50 states for such projects — Rhode Island received $2.1 million, Massachusetts $5.9 million and Connecticut $5.3 million.

Brownfield remediation projects, on average, leverage $17 per EPA dollar expended, according to Gardner. He also said the federal agency’s Brownfields Program creates additional benefits, such as increasing residential property values near remediated sites by 5 percent to 12 percent, and empowering states, communities and other stakeholders to work together to prevent, assess, safely clean up and reuse brownfields. The EPA notes that since the program’s inception in 1995 it has leveraged 90,363 jobs nationwide.

But transforming blighted brownfields into community assets is no easy task. It takes money — plenty of it — patience, often a public-private partnership and some creative thinking. One Massachusetts program, for example, encourages ground-mounted solar projects on brownfields and landfills.

On a contaminated brownfield near two schools, the city of New Bedford got inventive and contracted with Con Edison Solutions and BlueWave Capital to build a solar project. This solar installation is intended to be used to help support energy education and encourage students to consider working in the renewable-energy industry.

Successfully overhauling such properties also depends largely on a site’s contamination level, according to Cynthia Gianfrancesco, who runs the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s (DEM) Targeted Brownfields Assessment Program. The program began in 1996 as a pilot in communities, such as Providence, North Smithfield and Woonsocket, with long histories of manufacturing and heavy industry.

“Most of the sites in Rhode Island are heavily contaminated,” she said. “They were once textile mills and then became sites for jewelry manufacturing. We’re dealing with an industrial history of more than 200 years.”

Those centuries of incineration, smelting, metal plating, concrete manufacturing, etching and electroplating contaminated much of southern New England’s land and water. But a number of private and/or public projects has breathed new life into long-abused properties.

Since 1994, the EPA Brownfields Program has awarded Rhode Island $34.8 million, Massachusetts $106.3 million and Connecticut $71.8 million to fund a three-state total of 1,422 remediation projects. That 20-year total of $212.9 million helped clean up 301 properties in Rhode Island, 783 in Massachusetts and 338 in Connecticut, but it represents just a slice of the money that was needed to advance those projects.

“EPA brownfields funding is just a building block, not the entire block,” Gardner said. “Most of these projects need to cobble together funding from various sources. EPA money is just a piece of it. It’s like putting a jigsaw puzzle together.”

And those 1,422 brownfield remediation projects the EPA has helped fund since 1994 represent just a fraction of the southern New England sites plagued by contaminated soil, polluted waters and abandoned properties rife with toxic waste, such as asbestos and lead. Little Rhody, for instance, has some 1,800 brownfields, according to best estimates.

But the number of properties in southern New England contaminated by the region’s industrial past is slowly declining.

A once heavily polluted property, the Steel Yard is now a Providence attraction.

(See Joanna Detz/ecoRI News) ''Providence success stories'') From locomotive manufacturers to steel mills, Providence has a long history of industrialization. While the city’s manufacturing industry gave rise to an economic boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, few operating mills remain today.

It was with a slight tip of the hat to those industries that made Providence economically great that the Steel Yard was founded in 2002. The visionaries who started the nonprofit artists collective also wanted to acknowledge the legacy of environmental degradation that heavy manufacturing has had on the city and state’s natural resources.

The Steel Yard is in the city’s Olneyville neighborhood, a once flourishing industrial enclave for textile, jewelry and metal manufacturers. A dozen years ago, the site was closed and in disrepair. For years, Providence Steel had sprayed its finished girders with lead-based paint, with the overspray leaving high concentrations of lead in the property’s soil.

The cost to transform this 3.5-acre brownfield on Sims Avenue into a community asset was substantial. The eight-year remediation project cost nearly a million dollars, and was completed thanks to federal and state grants, fundraising efforts, and donated materials and labor. Today, the old Providence Steel buildings have been converted into more than 9,000 square feet of workspaces for artists, and classrooms for education and job training in the industrial arts. The property has become a signature city attraction.

The Steel Yard, however, isn’t the only Providence brownfield to enjoy an expensive makeover. Two Octobers ago, community members, neighbors and representatives from Groundwork Providence gathered to celebrate the completion of the Hope Tree Nursery, in an industrial area on the city’s West Side that once housed metal manufacturers.

Situated on the former Sprague Industries site, a brownfield still laden with residual toxins from its factory days — no soil can be removed, so the trees are grown in pots — Hope Tree Nursery now provides the Elmwood neighborhood access to affordable trees grown locally. The nursery’s physical presence also has improved the look and feel of Sprague Street.

Two distressed areas along the Woonasquatucket River have been revitalized and turned into community assets. Riverside Park, a former brownfield and high-crime area, is now a 6-acre neighborhood oasis. Its redevelopment brought with it a bike path, new housing and the opening of small grocery store, and crime has fallen sharply.

Contamination from the former Lincoln Lace and Braid factory — petroleum, metals and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) — had spread to this industrial river. It cost $991,000 — funded by state and federal money — to cealn up the property, which is now a passive greenspace connected via a bike path to other urban parks.

WaterFire Providence will soon make its new home on a three-parcel site on Valley Street once occupied by a rubber manufacturer and machine shop. The ongoing renovation includes a stormwater management system. The property also will be used as an incubator for artists and businesses, and will host after-school programs.

A 25-acre site on the Providence/Johnston line and bordered by the Woonasquatucket River, had been contaminated by lead and arsenic, until the early 2000s, when the Button Hole Golf Course opened. Today, the nine-hole course is a teaching center that brings golf to urban youth.

The city’s neighbor to the north, Pawtucket, another community with a rich industrial history, recently announced that renovations to the Festival Pier waterfront park off School Street will be completed at the end of November. The park is expected to open to the public Dec. 1.

When finished, the $2 million brownfield remediation of the Old State Pier property, a former oil terminal along the Seekonk River and home to the popular Chinese Dragon Boat Races, will feature a new plaza, lighting, benches, a canoe/kayak launching area and a boat ramp.

xxx Mosaico, a nonprofit community development corporation, has owned the the former National India Rubber Co. on Wood Street in Bristol for four years. Before that, the brownfield was in receivership, several buildings were in disrepair and there were outstanding DEM violations tagged to the 14-acre former Kaiser Mill Complex.

During its heyday, this industrial complex employed more than 1,200 people, and local families set their clocks to the mixture of solids, liquid particulates and gases belched from its smokestack at 7 a.m., noon and 5 p.m.

Mosaico applied for and received Targeted Brownfields Assessment Program funding from DEM to complete an environmental assessment of the property. The nonprofit then applied for and received a $200,000 EPA brownfields grant. The money is being used to clean up contamination, address stormwater management requirements and cap portions of the site with new landscaping.

Mosaico is seeking additional funding to complete improvements on the remainder of the site, which would allow for increased occupancy and economic development opportunities. About 60 percent of the space is occupied by some 25 companies, which range from boat builders to sign and skateboard makers.

The Thames Street Landing transformed an abandoned waterfront property in Bristol into a commercial development. (BETA Group Inc.)This popular waterfront town also features two other ambitious brownfield redevelopment projects — Thames Street Landing and Premier Thread.

Thames Street Landing was empty for three years before this redevelopment project began in 1999, on property originally used as a lumberyard. Most of the site’s contamination — lead, arsenic, petroleum and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) — resulted from production of coal, coke and lumber in the last 40 years of the 1800s. Some 20,000 yards of contaminated soil was removed from the 2.2-acre site, and the entire project cost $8.3 million, most of it privately funded.

This waterfront property now features retail establishments, a restaurant, offices, apartments and a hotel, transforming a once highly contaminated, abandoned lot into a central part of the town’s economic and social structure.

“The project spurred development around it, and the neighborhood took off,” said Kelly Owens, an associate supervising engineer for DEM and one of seven agency employees devoted to brownfield work. “It created some true economic development.”

The Thames Street site of the former Premier Thread factory and old Narragansett Electric manufactured gas plant is now high-end condominiums. This project, Owens said, also helped stimulate neighborhood development.

“We hope our funding helps fill in the blanks and reduce some uncertainty,” said the EPA’s Gardner. “Just about every town in New England had a mill or manufacturing facility. The Industrial Revolution certainly left a mark.”