Chris Powell: Yes, anti-COVID-19 campaign could do more damage than the virus

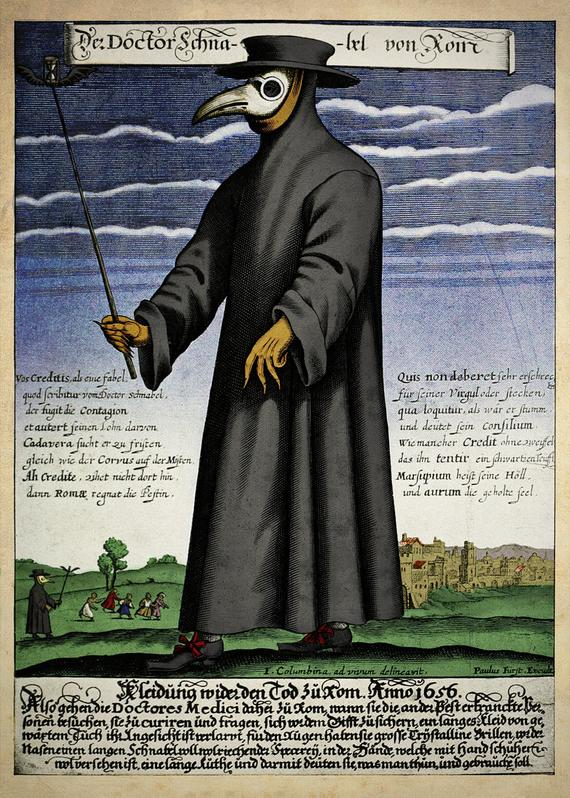

Plague doctor in 1656

As Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and other governors curtail more commerce, industry, employment and ordinary life in the name of containing the new virus sweeping the world, people are starting to question whether the precautions are going too far. Is containing the virus worth crippling the economy, bankrupting so many businesses, throwing millions out of work and pushing their households into insolvency, destroying retirement savings, and exploding the national debt?

The official response is making the virus sound like the plague that killed half of Europe in the 1300s. But many people sense that it may not be that bad, may be no worse than ordinary influenza, which kills tens of thousands of people in the United States every year without setting off any alarm. Indeed, ordinary flu in Connecticut this year already had hospitalized more than 1,300 people and killed more than 60 before the new virus infected its first hundred people and killed anyone in the state. The state Department of Public Health noticed the flu's toll but only in a statistical sense. Except for the families of those who died, nobody else seems to have noticed, though "social distancing" a few months ago might have prevented many of those deaths.

Few notice how traffic fatalities add up either -- more than 35,000 every year in the United States, even as most could be prevented by "lockdowns" like those now being imposed because of the new virus.

Despite all the hysteria, financial loss and inconvenience generated by closing orders, most people diagnosed with the new virus find it anticlimactic. That is, for most a positive test for the virus prompts no hospitalization or special medical intervention at all. Instead most people are just told to go home, get well soon, and call back if they don't, just as they would be told upon diagnosis for the flu or a bad cold. Sure enough, they go home and most get well soon.

Doctors and governors warn that for every diagnosis with the new virus there may be a hundred undiagnosed people carrying it but not showing symptoms, and even the asymptomatic may infect others. Or the asymptomatic may not infect anyone and may never suffer any symptoms at all. Indeed, last week a Nobel prize-winning Israeli scientist speculated that half the population may be naturally immune to the new virus, and Chinese research has suggested that blood type may correlate with susceptibility. So while the mere number of infections may sound scary, it is not so important.

What may be most important is the percentage of people infected who die or require hospitalization. As of March 22 in Connecticut, the fatality rate from infections with the new virus was just 2½ percent and the hospitalization rate about 18 percent. Frail elderly people were most at risk of dying in Connecticut and most deaths elsewhere from the disease have involved either the frail elderly or those with already weakened immune systems. Hard-hit Italy reported last week that 99 percent of its fatalities were from these high-risk groups.

Of course, if infection spreads widely enough, even an 18 percent hospitalization rate would overwhelm the medical system. So widespread testing and quarantining as necessary, as South Korea has done, might be the best response. A government more devoted to public health generally than to fantastically expensive and stupid imperial wars might help too. But since, as flu and traffic fatalities show, life is always a judgment call about risk, and since it is known who is most vulnerable to the new virus, why not just isolate them rather than everyone else? For as the self-inflicted economic damage becomes catastrophic, the cure may be worse than the disease.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, vin Manchester, Conn.