From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

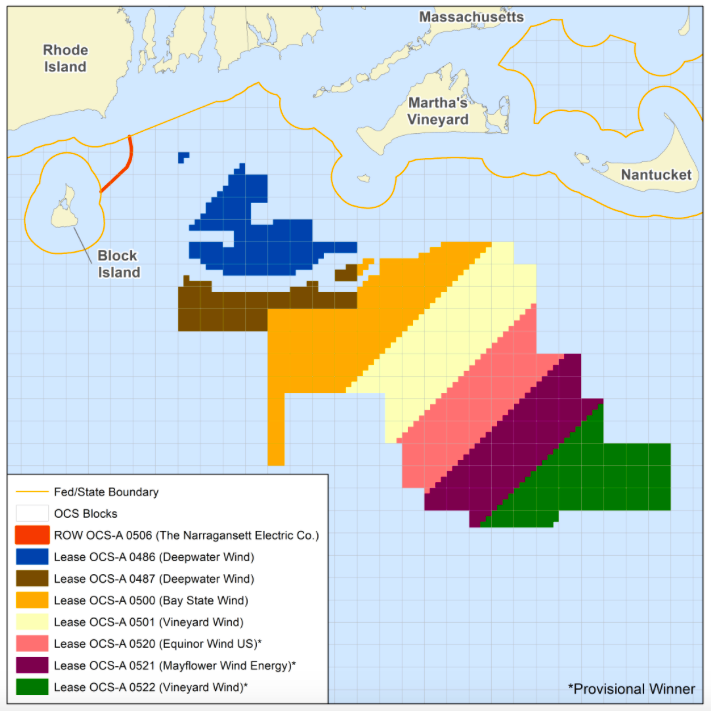

The demand for offshore wind continues, as the designated wind zones in waters south of Rhode Island, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket fill with projects.

At the June 11 meeting of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC), Grover Fugate, executive director, recounted the growing pains to accommodate as much as 22,000 megawatts of offshore wind.

“This industry has literally exploded overnight,” said Fugate, as he highlighted issues confronting several projects.

The 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind facility, for instance, is deadlocked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) over the project’s environmental impact statement.

“That’s not something that’s been done before in the NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) world,” Fugate said. “So we’re not quite sure where that is going to end up.”

The Nantucket Historical Commission is seeking $16 million from the Vineyard Wind developer, according to Fugate. The island town has sought funds to compensate for adverse visual impacts the 84 turbines may have on tourism.

Connecticut recently announced it wants to add 2,000 megawatts of offshore wind to the power grid but the state lacks approved offshore wind areas.

“Connecticut, of course, does not have any offshore sources,” Fugate said. “The closest ones to Connecticut are us (Rhode Island).”

Connecticut is already signed on for 300 megawatts from the Revolution Wind project located in one of four wind-lease areas that require CRMC approval.

Rhode Island has already signed up 400 megawatts from the same wind project managed jointly by Ørsted US Offshore Wind and the Massachusetts utility Eversource.

Massachusetts has a goal of 3,200 megawatts of offshore wind by 2035. It has already agreed to buy 800 megawatts from the Vineyard Wind project and the state has issued a request for proposal for an addition 800 megawatts that may come from the second half of the Vineyard Wind lease area.

Vineyard Wind went through a lengthy and contentious review for its initial wind facility and wants to meet with CRMC about a review of the second half of its wind-zone lease.

Bay State Wind, another Eversource and Ørsted project, is also moving forward with an 800-megawatt wind project in the same region. Fugate met with Bay State Wind’s CEO and discussed how the project fails to conform with a 1-mile spacing of turbines within its grid configuration.

Fugate said Bay State Wind is using a European design that doesn’t meet the fisheries requirement for U.S. projects.

“So they are taking that back under consideration,” Fugate said.

Vineyard Wind has filed a proposal to deliver 1.2 gigawatts of wind power to New York along a 95-mile transmission line from Vineyard Wind’s second wind zone, in the easternmost section of the federal wind-lease area. In all, New York is looking for some 9,000 megawatts of wind energy.

“If you add it all up it’s about 22,000 megawatts from New York to the Cape that's under consideration,” Fugate said.

He expressed frustration with the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for not requiring an extended analysis of proposed offshore wind project sites.

“If you don't get two years of baseline data you have no way of measuring the impact,” Fugate said. “That may be intentional on their part, I don't know. But we have pushed for baseline data so that you can measure before and after, so that you know what you just did and how to adjust to it. But without that baseline, we don't know what we just did.”

Cable congestion

The surge in offshore wind development has created a need for transmissions lines and onshore connections to the electric grid. Wakefield, Mass.-based Anbaric Development Partners is creating a renewable-energy center on a leased site at the former Brayton Point coal-fired power plant in Somerset, Mass. Anbaric wants to install two high-voltage electric cables from Brayton Point to serve wind facilities off the coast of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Ørsted would also like to run two cables from its Bay State Wind project to the mainland at Brayton Point.

The transmission lines would run through the the Sakonnet River along the easternmost channel of Narragansett Bay.

Fugate noted that the passage can only accommodate two power cables because of the narrow Stone Bridge corridor between Portsmouth and Tiverton. He said the activity at Brayton Point and other wind-facility operations within Narragansett Bay will be busiest during the summer, causing congestion along the East Passage, which runs between Newport and Jamestown.

“There’s a huge interference with a lot of existing uses down there,” Fugate said.

Federal review

NOAA officials will perform a three-day review of CRMC’s overall coastal program, including a public hearing scheduled for June 18. The review, required every seven years, will culminate with a report of findings that will offer suggested and required actions needed to adhere to federal grant requirements.

In a worst-case scenario, CRMC could face sanctions, which include a loss of federal funding for CRMC’s coastal programs. More than half of CRMC’s budget comes from federal sources.

NOAA’s last evaluation of CRMC was conducted in 2010.

The public hearing will be held at the Department of Administration building, conference room A, One Capital Hill, at 6 p.m.

Matunuck seawall

Hearings are expected in the fall for phase two of a seawall project on Matunuck Beach Road, in South Kingstown, R.I. The first phase was a highly controversial and meaningful case for the CRMC, as it confronts sea-level rise and shoreline erosion from climate change.

Tim Faulkner is an ecoRI News journalist.