—Photo by ThirstyFish.com

Progressive era cartoon

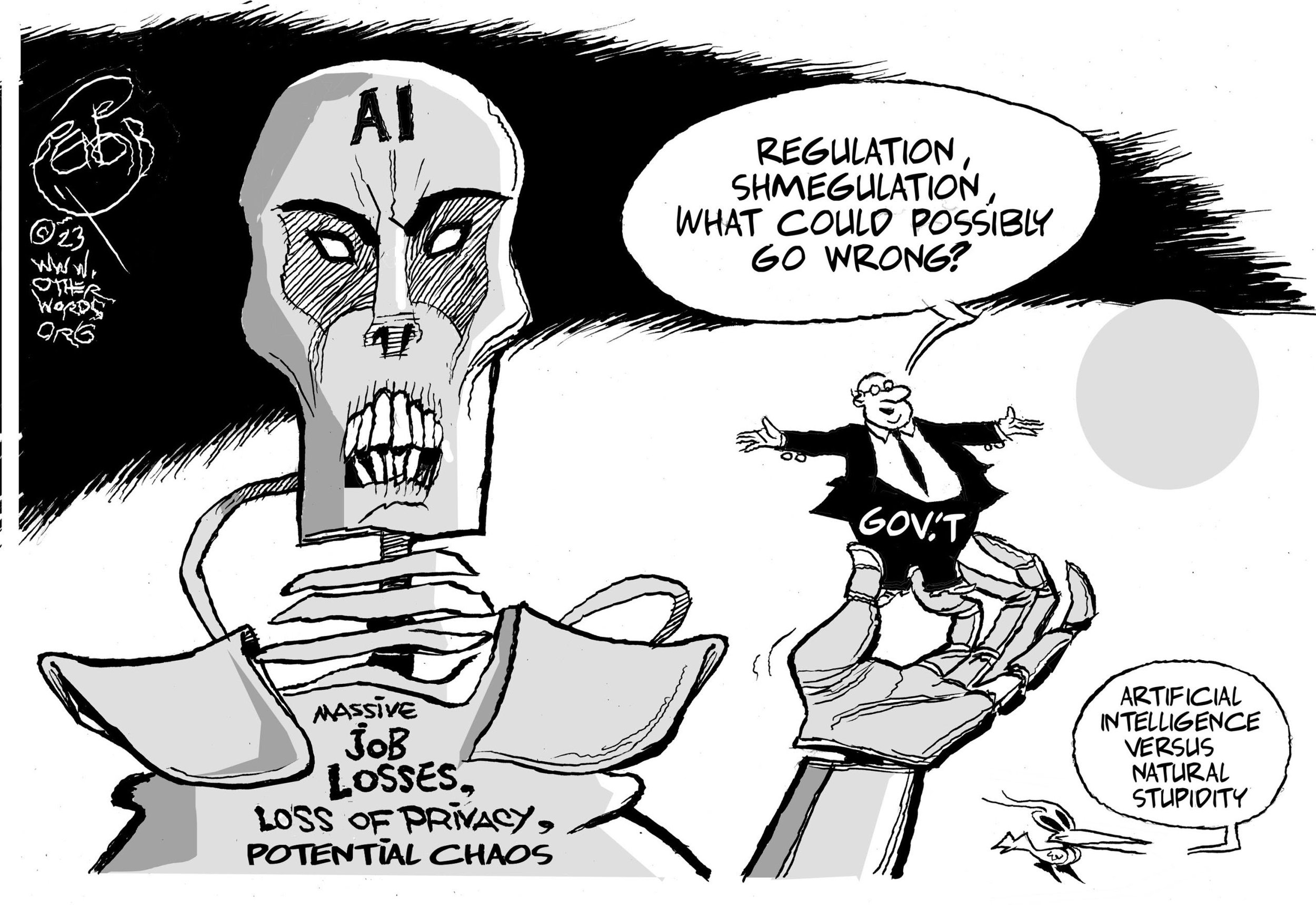

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

A new, disturbing milestone has been confirmed in the latest Forbes World Billionaires List. The U.S. billionaire class is now larger and richer than ever, with 813 ten-figure oligarchs together holding $5.7 trillion.

This is a $1.2 trillion increase from the year before — and a gargantuan $2.7 trillion increase since March 2020.

The staggering upsurge shows how our economy primarily benefits the wealthy, rather than the ordinary working people who produce their wealth. Even worse, those extremely wealthy individuals often use these assets to undermine our democracy.

Billionaires have enormous power to influence the political process. They spent $1.2 billion in the 2020 general election and more than $880 million in the 2022 midterms. Even when their preferred candidates aren’t in office, our institutions are still more likely to respond to their policy preferences than the average voter’s, especially when it comes to taxes.

The vast majority of Americans, including 63 percent of Republicans, support higher taxes on the wealthy. Yet our representatives consistently fail to deliver. A quintessential example was Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cuts for corporations and the rich — the most unpopular legislation signed into law in the past 25 years.

Though backers promised the tax cuts would benefit all Americans, a recent report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities revealed that the primary beneficiaries were the top 1 percent.

The good news? Those cuts are set to expire after next year. So we’ll have an opportunity for a new tax reform — one that raises more money for the services we rely on while protecting our democracy from extreme wealth concentration.

President Joe Biden’s Billionaire Minimum Income Tax (BMIT) is one promising proposal. By raising the top tax rate and taxing unrealized capital gains, the BMIT seeks to repair a system where billionaires pay a lower average tax rate than working people. It would raise $50 billion a year over the next decade, making our tax system a bit more equitable.

Senator Ron Wyden’s (D.-Ore.) similarly named Billionaire Income Tax (BIT) is more straightforward. It would target asset gains that can easily be tracked by the public, like a billionaire’s stock holdings in a publicly traded company.

Another idea? A well-designed progressive tax on billionaire wealth.

A modest 5 percent tax on all wealth above $1 billion would raise more than $244 billion this year alone. And that’s likely an underestimate, since some billionaires keep their wealth concealed from Forbes. Wealth-X, a private research firm, identified 955 billionaires in their Census last year, 142 more than what Forbes just registered.

A wealth tax wouldn’t hurt investment and innovation — most innovation in the U.S. is driven by people worth less than $50 million. But for billionaires, it would function “as a constraint on their rate of wealth accumulation,” according to Patriotic Millionaires, a group of wealthy people who support higher taxes on the rich.

Of course, a wealth tax alone isn’t enough to ensure the safety of our democracy. We also need campaign finance reform to limit political spending. And stronger labor unions could prevent extreme concentrations of wealth from occurring in the first place. Unions not only increase the collective power of workers, they also close wage gaps between workers and CEOs.

Finally, we need better tax enforcement. The Inflation Reduction Act gave the IRS more resources to track down wealthy tax dodgers, and now the agency is projecting an unexpected windfall in tax revenue over the next decade.

That’s a great first step towards strengthening our democracy and democratizing our economy. Now let’s take the next step and fix the tax code itself.

Boston-based Omar Ocampo is a researcher for the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies.