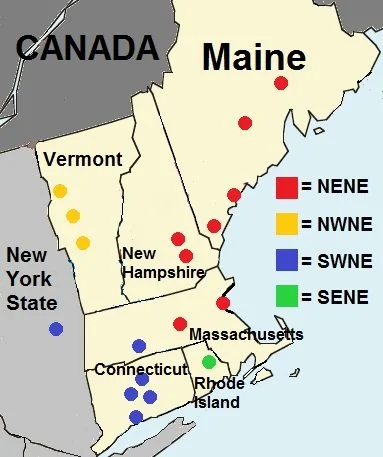

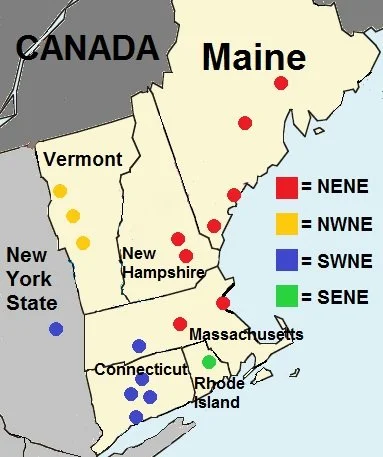

Northeastern (NENE), Northwestern (NWNE), Southwestern (SWNE), and Southeastern (SENE) New England English, as mapped by the Atlas of North American English.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

There’s an amusing semi-controversy in the Boston mayoral race. It’s about City Councilor Annissa Essaibi George allegedly leaning into her Boston accent – or, more specifically, her accent from the Dorchester section of that city. That’s where she grew up, in a section of the city usually associated with Irish-Americans, though she herself is of Polish and Tunisian background. The accent has been described as an attempt to appeal to her predominately white base in her run against City Councilor Michelle Wu, who is originally from the Chicago area and whose base includes many people of color. Meanwhile, Boston’s white base continues to shrink.

So far, anyway, Mrs. George’s Dorchester/South Boston accent, which some find grating and some charming (Saturday Night Live has had fun with it over the years) hasn’t seemed to have helped her much: Ms. Wu remains far ahead in the polls.

But the matter got me thinking about accents. Mass media and demographic mixing have tended to dilute old accents, especially in places like Boston, with so many people having come in from around the world to work and/or attend the region’s multitude of colleges and universities.

In New England, the old accents are weakening. I think of the accents of my late father and his father. My paternal grandfather had a pronounced rural Yankee sound, almost a drawl, that recalled natives of the Maine Coast and even Cape Cod a century or more ago. My father had a milder version of the same thing. His five children retain only traces of it, mingled with my late mother’s Minnesota accent. She also had some (fake?) Southern tones from living in Florida half the year as a girl and then going to high school in Virginia. And my siblings and I have picked up fragments of accents and diction from the places we have lived outside New England.

Of course, even among old Yankee accents, there’s variety in the region. Language experts say much of this can be attributed to where the early colonists came from in England hundreds of years ago – say from the West Country, East Anglia or the Midlands.

Sometimes an accent that some might consider off-putting doesn’t bother others. Consider Franklin Roosevelt’s plummy Hudson River squire voice, which he made no effort to modify for political or other reasons. In part because he could express empathy, confidence and ingenuity to the masses, he became their tribune even as many others from his background were seen as greedy, arrogant and unfeeling about the challenges facing the middle class and the poor in the Great Depression.

But FDR’s accent might be an electoral killer these days.

While historic American accents have long been in decline, the waves of immigrants from non-English-speaking countries over the past few decades have added new and interesting ones to our language stew – and words, too. That English is such an avid absorber of words from other languages means that it has the largest vocabulary of any language – probably its greatest strength and something that’s made it the closest thing to an international language. We’re fortunate to have it as our main tongue.