Via ecoRI News (ecori.og)

Researchers studying the sharp decline between 1980 and 2010 in documented landings of the four most commercially important bivalve mollusks — eastern oysters, northern quahogs, soft-shell clams and northern bay scallops — have identified the causes.

Warming ocean temperatures associated with a positive shift in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which led to habitat degradation including increased predation, are the key reasons for the decline of these four species in estuaries and bays from Maine to North Carolina, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The NAO is an irregular fluctuation of atmospheric pressure over the North Atlantic Ocean that impacts both weather and climate, especially in the winter and early spring in eastern North America and Europe. Shifts in the NAO affect the timing of species’ reproduction and growth, the availability of phytoplankton for food, and predator-prey relationships, all of which contribute to species abundance. The findings appear in Marine Fisheries Review.

“In the past, declines in bivalve mollusks have often been attributed to overfishing,” said Clyde Mackenzie, a shellfish researcher at NOAA Fisheries’ James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory, in Sandy Hook, N.J., and lead author of the study. “We tried to understand the true causes of the decline, and after a lot of research and interviews with shellfishermen, shellfish constables, and others, we suggest that habitat degradation from a variety of environmental factors, not overfishing, is the primary reason.”

Mackenzie and co-author Mitchell Tarnowski, a shellfish biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, provide details on the declines of these four species. They also note the related decline by an average of 89 percent in the numbers of shellfishermen who harvested the mollusks. The landings declines between 1980 and 2010 are in contrast to much higher and consistent shellfish landings between 1950 and 1980.

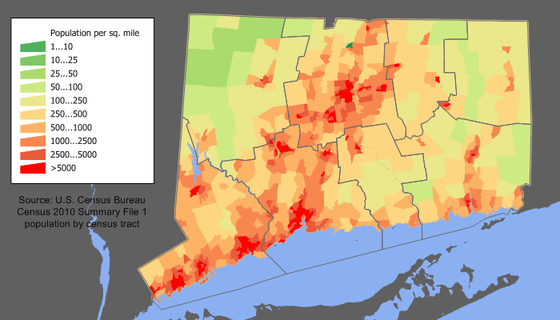

Exceptions to these declines have been a sharp increase in the landings of northern quahogs in Connecticut and American lobsters in Maine. Landings of American lobsters from southern Massachusetts to New Jersey, however, have fallen sharply as water temperatures in those areas have risen.

“A major change to the bivalve habitats occurred when the North Atlantic Oscillation index switched from negative during about 1950 to 1980, when winter temperatures were relatively cool, to positive, resulting in warmer winter temperatures from about 1982 until about 2003,” Mackenzie said. “We suggest that this climate shift affected the bivalves and their associated biota enough to cause the declines.”

This graph shows the rise and fall of soft-shell clam landings from 1950 to 2005. (Clyde Mackenzie)

Research from extensive habitat studies in Narragansett Bay and in the Netherlands, where environments including salinities are very similar to the northeastern United States, show that body weights of the bivalves, their nutrition, timing of spawning, and mortalities from predation were sufficient to force the decline. Other factors likely impacting the decline were poor water quality, loss of eelgrass in some locations for larvae to attach to and grow, and not enough food available for adult shellfish and their larvae.

“In the Northeast U.S., annual recruitments of juvenile bivalves can vary by two or three orders of magnitude,” said Mackenzie, who has been studying bay scallop beds on Martha’s Vineyard with local shellfish constables and fishermen monthly during warm seasons for several years.

In late spring to early summer of this year, a cool spell combined with extremely cloudy weather may have interrupted scallop spawning, leading to what looks like poor recruitment this year. Last year, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard had very good harvests due to large recruitments in 2016.

“The rates of survival and growth to eventual market size for shellfish vary as much as the weather and climate,” Mackenzie said.

Weak consumer demand for shellfish, particularly oysters, in the 1980s and early 1990s has shifted to fairly strong demand as strict guidelines were put in place by the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference in the late 1990s regarding safe shellfish handling, processing, and testing for bacteria and other pathogens.

Enforcement by state health officials has been strict. The development of oyster aquaculture and increased marketing of branded oysters in raw bars and restaurants has led to an increase in oyster consumption in recent years.

Since the late 2000s, the NAO index has generally been fairly neutral, neither very positive nor negative. As a consequence, landings of all four shellfish species have been increasing in some locations. Poor weather for bay scallop recruitment in both 2017 and 2018, however, will likely mean a downturn in landings during the next two seasons.