"Sailing Off Morris Island (Chatham, Cape Cod),'' by BOBBY BAKER (copyright Bobby Baker Fine Photography).

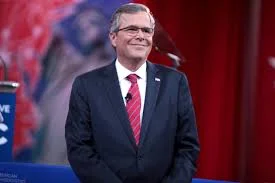

Paul A. Reyes: Jeb Bush has had freebies his whole life

The Republican Party has struggled for years to attract more voters of color. In a recent campaign appearance, candidate Jeb Bush offered yet another useful case study of how not to do it. At a campaign stop in South Carolina, the former Florida governor was asked how he’d win over African-American voters. “Our message is one of hope and aspiration,” he answered. So far, so good, right?

“It isn’t one of division and get in line and we’ll take care of you with free stuff. Our message is one that is uplifting — that says you can achieve earned success.”

Whoops.

With just two words — “free stuff” — Bush managed to insult millions of black Americans, completely misread what motivates black people to vote, and falsely imply that African Americans are the predominant consumers of vital social services.

First, the facts.

Bush’s suggestion that African-Americans vote for Democrats because of handouts is flat-out wrong. Data from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies shows that black voters increasingly preferred the Democratic Party over the course of the 20th Century as it stepped up its support for civil rights.

These days, more than 90 percent of African Americans vote for the Democratic Party’s presidential candidates because they believe Democrats pay more attention to their concerns. Consider that in the two GOP debates, there was only one question about the “Black Lives Matter” movement. When they do comment on it, Republican politicians feel much more at home criticizing that movement against police brutality than supporting it.

Bush is also incorrect to suggest that African-Americans want “free stuff” more than other Americans. A plurality of people on food stamps, for example, are white.

Moreover, government assistance programs exist because we’ve decided, as a country, to help our neediest fellow citizens. What Bush derides as “free stuff” — say, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and school lunch subsidies — are a vital safety net for millions of the elderly, the poor, and children, regardless of race or ethnicity.

How sad that Bush, himself a Catholic, made his comments during the same week that Pope Francis was encouraging Americans to live up to their ideals and help the less fortunate.

Finally, Bush’s crass comment is especially ironic coming from a third-generation oligarch whose life has been defined by privilege.

Bush himself is a big fan of freebies. The New York Times has reported that, during his father’s 12 years in elected national office, Bush frequently sought (and obtained) favors for himself, his friends, and his business associates. Even now, about half of the money for Bush’s presidential campaign is coming from the Bush family donor network.

And what about those corporate tax breaks, oil subsidies and payouts to big agricultural companies Bush himself supports? Don’t those things count as “free stuff” for some of the richest people in our country?

It’s also the height of arrogance for Bush to imply that African Americans are strangers to “earned success.” African-Americans have been earning success for generations, despite the efforts of politicians like Bush — who purged Florida’s rolls of minority voters and abolished affirmative action at state universities.

If nothing else, this controversy shows why his candidacy has yet to take off as expected. His campaign gaffes have served up endless fodder for reporters, pundits, and comics alike.

Sound familiar?

As you may recall, Mitt Romney helped doom his own presidential aspirations by writing off the “47 percent” of the American people he said would never vote Republican because they were “dependent upon government.”

In Romney’s view, they’re people “who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.”

Sorry, Jeb. The last thing that this country needs is another man of inherited wealth and power lecturing the rest of us about mooching.

But not touching

Guaranteed worm in every ear of corn

Dick and Dot Wingate at their Studio Farm, in Voluntown, Conn. (David Smith/ecoRI News photo)

By DAVID SMITH/ecoRI News contributor

VOLUNTOWN, Conn.

Back in 1963 it seemed natural for Dick and Dot Wingate to start growing vegetables to feed their family, only now the family has grown to include many people who enjoy the fruits of their labor at two farmers markets in southeastern Connecticut.

Look for the small banner inside the tent that reads “Studio Farm.” It was a name for their 35-acre homestead that stuck. Sit on the back porch of their circa -1753 farmhouse and they might bring out a copy of an old newspaper to explain that monicker. In it there is an article about the farm and its former tenants from around 1916 — movie stars of the silent-film era led by actor and producer Joseph Byron Totten.

Look to the north from the porch and you’ll see a more than 100-year-old stone building that is now a barn. Look closer, and you’ll see bars on the window. It was once used as a “jail” for a Western film.

There also is a story about a secluded area out back shielded by a tall ledge that purportedly was once the site of a still that produced booze during Prohibition.

They might also tell you the story about one cold October day the same year they moved in when a bucket of ashes left on the porch started a fire that spread to the roof. The volunteer fire department saved the day and the house. Dick was at work as a shop teacher at Stonington High School when he got the news from a school official. He was told that his seven-month pregnant wife, Dot, and his two children, Mark and Belinda, were OK.

“I was surprised when I got home to see the house still standing,” recalled the 78-year-old.

Things are much calmer at the farm these days, well, except for the visits by a black bear. It seems the couple’s multitude of fruit trees, strawberry plants and blueberry bushes are too much for the local wildlife to ignore. The bear has left calling cards on the ground in the groves that provide clues to its diet.

Gardens surround the barn and two greenhouses. The more than two dozen fruit trees provide a variety of apples, pears and peaches.

The Wingates were certified organic farmers for nine years, but let that certification lapse, not because they have changed their farming methods. It was simply a matter of cost. The last time they were certified the price tag was $750.

The process involves a visit from a person from an independent certification group. Seed packets are reviewed to check and see if they are organic. Crop rotation and planting plans are studied, as well as the harvest numbers from the previous season. There also was a rule requiring fields be numbered so that if there was a problem with the crop it could be traced to a particular area.

“We can’t say we are organic,” Dick said, “but we can say that we are growing using organic standards.”

It’s not a question that comes up frequently. The couple said new customers ask whether they are organic growers, but their regular customers already know.

“So many people come to the farm and see the weeds,” said Dick, noting that using herbicide to control them isn’t an option. “People thank us for not using herbicides”

There are some organic sprays, made from various flowers, that are allowed, but they are contact sprays — meaning they must land on the bug — and aren’t very efficient.

The Wingates originally got the organic certification at the urging of their daughter Belinda Learned. When they tried to get into the Stonington Farmers Market, they were rebuffed because the group wanted an organic farm member. That was 13 years ago.

Family affair The Wingates are joined at the market in a field next to the Stonington Borough town dock by their daughter Belinda and her husband, Ed Learned, owners of the 105-acre Stonyledge Farm in North Stonington. The Learneds sell pasture-raised beef, pork, eggs and chicken, along with a few vegetables under the same tent.

If you visit their tent, you might see four generations of the family. The Wingates, Learneds and Belinda’s daughter, Marcia, and her children Bradley and Annalise.

Belinda also has three sons who operate the 115-acre Valley View Dairy on East Clark Falls Road in North Stonington. It’s about 1.5 miles from her farm.

The Learneds have a 98-foot-by-30-foot greenhouse. Dot starts the vegetables from seed in her greenhouse in February and, when the plants are ready to be transplanted, they are brought to this larger greenhouse to mature.

Dick said he never wanted teaching to be the sole source of their income. His starting salary was around $5,200. His wife would later work for 22 years in the Ledyard School district teaching business classes.

So, 20 years ago when they had extra vegetables, jams and fruit they would put it out front on a wooden stand at their farm, with a plastic container for people to leave money. They used that money to send their kids to an adventure camp in Massachusetts.

Then, 13 years ago, they got their foot in the door at farmers markets because of that organic certification. Dick said that years ago he used to spray his fruit trees to combat bugs, but that reading the label showed him that it contained some nasty stuff.

“Three to four years after I stopped spraying, I started to see praying mantis eggs on the raspberries,” he said. “I realized that I was killing beneficial insects as well as the bad bugs.”

The couple now grows about 36 varieties of tomatoes, including heirlooms. Tomatoes, and various types of lettuce, are Studio Farm’s big sellers.

“They don’t look perfect,” Dick said. “They are not spherical. I had one lady look them over and said that one had a split in it. She denied herself a great tasting meal.”

And sometimes there are years when worms can be found in the ears of corn they sell. So, like any good farmer, Dick sold this corn with the guarantee that each ear came with a worm. He recalled another farmer marketed his corn with the promise that each ear came with a “free fishing worm.”

Studio Farm also sells a mesclun mix, which features a variety of lettuces, arugula, dill, basil and spicy mustard leaves. They sell 9 ounces of the mesclun mix for $5 and 5 ounces of arugula for $4.

Dot, 77, said it usually takes her three hours on a Friday to put together just 12 packages for that weekend’s markets. The leaves have to be washed, sorted and packaged. It is one product that usually sells out.

And as far as the variety of jams they sell, Dot said they probably sell some 1,800 jars a season.

The youngest of the Wingates’ four children is Matthew. He is expected to retire from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 18 months and has talked about returning and opening a farm store — a place for local farmers to bring their crops.

It’s a question of finding a good place with plenty of traffic, Dick said.

The Stonington Farmers Market is open every Saturday from 9 a.m.-noon until the first Saturday in November, when it moves to the Stonington Velvet Mill, 22 Bay View Ave., until the end of May. The Wingates and Learneds also sell their wares at the Denison Farmers Market, 120 Pequotsepos Road in Mystic, each Sunday from noon-3 p.m.

Concealment goes to school by Chris Powell

When a public school teacher is suspended amid investigation of a complaint that he molested a student, what are the urgent objectives of a school superintendent? In Stafford and indeed in most Connecticut towns those objectives include preventing the public from finding out.

'Katrina Then and Now'

The march to Montgomery, 1965

Nancy Gaucher-Thomas: The centrality of art

Living in Rhode Island for the past 20 years has been a great experience for me. Accessibility is key. People, no matter what their socio-economic status, are accessible and available to offer their expertise and help in making Rhode Island a better place. This is the single greatest thing about our state.

Because of this accessibility, we have the potential to make things happen very quickly.

As an artist with a background in advertising, I see the possibilities and those possibilities are what keep me here. I see the enthusiasm in friends and colleagues as they speak about Rhode Island and why it is a special place. The resounding answer is always: Rhode Island has everything. It is a place rich in culture, steeped in history, with some of the best learning institutions in the world, and a true melting pot surrounded by beautiful sea and landscapes.

How important are the arts to Rhode Islanders? What can we say about the arts that hasn’t already been said? Do people really “get it”? Given my experience with many different arts organizations and artists, and the fact that Rhode Island’s population is heavily composed of people working in the various art sectors, I think they do get it.

Art can have amazing power to foster collaboration between different societies and cultures. Art can be a powerful way to bring communities together. Art is powerful in its simplicity. It can convey ideas across classes and cultures because of its lack of reliance on language. This makes it one of the most powerful tools of communication.

In fact, research proves that a greater focus on the arts in a city creates social cohesion and better civic engagement. Creation of community art helps citizens work together to create shared visions of their ideals, values and hopes for the future. The arts bring people together, all shapes and sizes, ethnic backgrounds, religions; there are no barriers. Artists think big, they have big ideas and can implement them with the help of other artists and creative types and organizations. Artists are quite often one step ahead of everyone else in seeing the big picture. Artists are enthusiastic about getting involved, collaborating with others to make an even bigger impact on how the state is seen and perceived.

Art is an important way to document our collective present so that future generations may have greater understanding of our ways of thinking, values and more. Reaching back into time, the cave paintings of prehistoric times provide one of the last few glimpses of how these people lived and of their religious and moral values. Art is a deceptively simple way to access cultures that might otherwise be forgotten.

Art has long been a tool of protest and an inciter of social change. Art also has the capacity to heal, as therapeutic art is now commonly used to alleviate psychological trauma.

As Rhode Island moves into a more defined outreach for tourism, as well as economic development, with an effort to welcome the biotech sector in a more unified way, we will see art take its place to inspire, promote and communicate as our state ventures forth, as it has since its founding, with creating new opportunities and inviting others to join in.

I am proud to play my part to encourage the bringing of art to the table at the beginning, middle and end of our processes. As the founder of the Art League of Rhode Island, I see such integration as the soul of our mission. As the founder, along with Rhode Island artist Gretchen Dow-Simpson, of the Fourth Annual Arts Marketplace: Pawtucket, I look forward to welcoming more than 50 artists from throughout the region this Sept. 26 and 27 to the Pawtucket Arts Armory (ArtsMarketplacePawtucket.com).

These artists and those who attend this free event from throughout the state and region will be participating in, and celebrating, our state’s focus on commerce, diversity, tourism and quality of life. We will celebrate the rol that creativity can play in Rhode Island's success, now and in our future.

Nancy Gaucher-Thomas is an artist from East Greenwich, R.I. She had help writing this piece from Gretchen Dow Simpson, an artist from Providence.

David Warsh: After '08 Close Call Can Bankers Avoid Another Depression?

SOMERVILLE, Mass. So much for the first two depressions, the one that happened in the 20th Century, and the other that didn’t happen in the 21st. What about that third depression? The presumptive one that threatens somewhere in the years ahead.

Avoiding the second disaster, when a full-blown systemic panic erupted in financial markets in September 2008 after 14 months of slowly growing apprehension, turned on understanding what precipitated and then exacerbated the first disaster, the Great Depression of the 1930s.

By the same token, much will depend on how the crisis of 2007-08 comes to be understood by politicians and policy-makers in the future.

The panic of ’08 wasn’t described as such at the time – it was all but invisible to outsiders, and understood by insiders only at the last possible moment.

It occurred in a collateral-based banking system that bankers and money-managers had hastily improvised to finance a 30-year boom often summarized as an era of “globalization.”

The logic of this so-called “shadow banking system” has slowly become visible only after the fact.

The panic was centered in a market that few outside the world of banking even knew to exist. Its very name – repo – was unfamiliar. The use of sale and repurchase agreements as short-term financing – some $10 trillion worth of overnight demand deposits for institutional money managers, insured by financial collateral – had grown so quickly since the 1980s that the Federal Reserve Board gave up measuring it in 2006.

The panic led to the first downturn in global output since the end of World War II, and the ensuing political consequences in the United States, Europe, and Russia have been intense.

But the banking panic itself was the more or less natural climax to a building spree that saw China’s entry into the world trading system, the collapse of the USSR, and many other less spectacular developments – all facilitated by an accompanying revolution in information and communications technology.

Gross world product statistics are hard to come by – the concept is too new – but however those years are understood, as one period of expansion of world trade or two, punctuated by the 1970s, growth since the trough of the Great Depression is unique in global history.

The much-ballyhooed subprime lending was only a proximate cause. It was a detonator attached to a debt bomb that fortunately didn’t explode, thanks to emergency lending by central banks, backed by their national treasuries, that alleviated the fear of irrational ruin.

Instead of Great Depression 2.0, the loans were mostly repaid.

But what had occurred was almost completely misinterpreted by both the Bush and Obama administrations. What happened is still not broadly understood, even among economists.

Let me briefly recapitulate the story I have been telling here since May – mainly an elaboration of the work of a handful of economists involved in the financial macroeconomics project of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Panics We Will Always Have With Us

Banks have been a fixture of market economies since medieval times. Periodic panics have been a feature of banking since the seventeenth century, usually occurring at intervals of ten to twelve years. Panics are always the same: en masse demands by depositors – in modern parlance, by holders of bank debt – for cash.

Panics are a problem because the cash is not there – most of it has been lent out, many times over, in accordance with the principles of fractional banking, with only a certain amount kept in the till to cover ordinary rates of withdrawal.

In the 18th Century, Sir James Steuart argued for central banks and government charters. His rival Adam Smith advocated less invasive regulation, consisting of bank-capital and -reserve requirements and, having ignored Steuart, won the argument completely, as far as economists were concerned. Bankers were less persuaded. After the Panic of 1793, the Bank of England began lending to quell stampedes.

Panics continued in the 19th Century and, as banks grew larger and more numerous, became worse. After the Panic of 1866 shook the systems, former banker Walter Bagehot took leave from his job as editor of The Economist to set straight the directors of the Bank of England. In Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, he spelled out three basic rules for preventing them panics from getting out of hand: lend freely to institutions threatened by withdrawals, at a penalty rate, against good collateral. Thereafter, troubled banks sometimes closed, but panics in the United Kingdom ceased.

Panics continued in the United States. The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were supposed to stop them; they didn’t. There were panics in 1873, 1884 and 1893. At least the statutes created a national currency, backed by gold, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to manage both the paper currency and the banks.

Since then, three especially notable panics have occurred in the U.S. in the last hundred years – in 1907, in 1930-33, and in 2007-8.

The 1907 panic began with a run on two New York City banks, then spread to the investment banks of their day – the new money trusts. The threatened firestorm was quelled only when the New York Clearing House issued loan certificates to stop the bank run and J.P. Morgan organized the rescue of the trusts.

The episode led, fairly directly, to the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System – what turned out to be a dozen regional banks in major banking cities around the country, privately owned, including an especially powerful one in New York, and a seven-member board of governors in Washington, D.C., appointed by the president.

Legislators recognized that creating the Fed amounted to establishing a fourth branch of government, semi-independent of the rest, and a great deal of care and compromise went into the legislation. Under the leadership of Benjamin Strong, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who had served as Morgan’s deputy in resolving the 1907 crisis, and who enjoyed widespread confidence in both banking and government circles as a result, the Fed got off to a good start.

In the Panic of 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, banks were able to issue emergency currency under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act; the Fed was not yet functioning. The new central bank managed its policies adroitly enough in the short, sharp post-war recession of 1920-21 to gain a measure of self-confidence. In 1923, it began actively managing the ebb and flow of interest rates through “open market operations,” buying and selling government bonds for its own account.

Then Strong died, in 1928, leaving a political vacuum. That same year, disputatious leaders within the Fed, its governors in Washington and its operational center in New York, and their counterparts in the central banks of Britain, France and Germany, began to make a series of missteps that, cumulatively, may have led to the Great Depression. Investment banker Liquat Ahamed has argued as much in Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, drawing on many years of economic and historical research.

Starting in January 1928, the New York Fed stepped sharply on its brakes, hoping to dampen what it regarded as excessive stock market speculation. Instead the market surged, then crashed in October 1929. A sharp recession had begun.

A series of bank failures began, but the methods by which the industry had coped with such runs before the central bank was established were held in abeyance, awaiting intervention by the Fed. Instead of acting, the Fed tightened.

Twice more, in 1931, and in early 1933, waves of panic swept segments of the banking industry around the country with corresponding failures of hundreds of banks – everywhere but New York. (There was no deposit insurance in those days.)

Each time the Fed stood by, declining to lend or otherwise ease monetary stringency. Meanwhile Herbert Hoover set out to balance the federal budget. By March 1933, banks in many states had been closed by executive order.

Franklin Roosevelt defeated Hoover in a landslide in November 1932. The subsequent March, Roosevelt and a heavily Democratic Congress began the New Deal. (Inauguration of the new president was subsequently moved up to January.) With unemployment rates reaching 25 percent and remaining stubbornly high, the panics of the early ’30s were quickly forgotten. In any event, they had ceased.

Economists of all stripes offered prescriptions. Finally, in 1936, John Maynard Keynes, in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, dramatically recast the matter. Because wages would inevitably be slow to fall, an economy could become trapped in a high-unemployment equilibrium for lengthy periods. Only government could intervene effectively, providing fiscal stimulus to create more jobs, returning a stalled economy to a full-employment equilibrium.

Keynesian ideas gradually conquered the economics profession, especially after they were restated by Sir John Hicks and Paul Samuelson in more traditional terms. Soon after World War II, the new doctrine was deployed in the industrial democracies of the West. Fiscal policy, meaning raising and lowering taxes periodically, and manipulating government spending in between, would be the key to managing, perhaps even ending, business cycles. The influence of money and banking were said to be slight.

Starting in 1948, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, two young economists associated respectively with the University of Chicago and the NBER, began a long rearguard action against the dominant Keynesian orthodoxy. It reached a climax with the publication, in 1963, of A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, a lengthy statistical study of the Fed’s conduct of monetary policy. Its centerpiece was a reinterpretation of the Great Depression.

The Fed, far from having been being powerless to affect the economy, Friedman and Schwartz argued, had turned “what might have been a garden-variety recession, though perhaps a fairly severe one, into a major catastrophe,” by permitting the quantity of money to decline by a third between 1929 and 1933.

Peter Temin, economic historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, took the other side of the argument. Shocks produced by World War I were so severe that, exacerbated by commitments to an inflexible gold standard, a dozen years later, they caused the Depression. Central banks could scarcely have acted otherwise.

The argument raged throughout the ’70s. By the early ’80s, a young MIT graduate student named Ben Bernanke concluded that Friedman was basically correct: Monetary policy, especially emergency last-resort lending, was very important. He and others set out to persuade their peers. By a series of happy coincidences, Bernanke had been in office as chairman of the Fed just long enough to recognize the beginning of the panic for what they were in the summer of 2007. And so fifty years of economics inside baseball was swept away in a month of emergency lending in the autumn of 2008. Great Depression 2.0 was avoided. Friedman – or at least Bagehot – had been right.

This is a very different story than the one commonly told. More of that in a final episode next week.

Meanwhile, even this brief account raises an interesting question. How was it that the United States enjoyed that 75-year respite from panics – Gary Gorton calls it “the quiet period” – in the decades after 1934?

Why We Had the Quiet Years

With respect to banking, four measures stand out among the responses to the Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression:

* President Roosevelt explained very clearly the panic that had taken hold in the weeks before his inauguration in his first Fireside Chat, “The Banking Crisis,” and why he had declared a bank holiday to deal with it. He had taken the U.S. off the gold standard, too, but didn’t complicate matters by trying to explain why. As Gorton has pointed out, Roosevelt was careful not to blame the banks.

Some of our bankers had shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people's funds. They had used the money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was, of course, not true in the vast majority of our banks, but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity and to put them into a frame of mind where they did not differentiate, but seemed to assume that the acts of a comparative few had tainted them all. It was the government's job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible. And the job is being performed.

* The Banking Act of 1933, known as the Glass-Steagall Act for its sponsors, Sen. Carter Glass (D-Virginia) and Rep. Henry Steagall (D-Alabama), tightly partitioned the banking system, relying mainly on strong charters for commercial banks of various sorts. Securities firms were prohibited from taking deposits; banks were prohibited from dealing or underwriting securities, or investing in them themselves. (The McFadden Act of 1927 already had prohibited interstate banking.)

* Congress established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to oversee the deposit insurance provisions of the 1933 Banking Act . Small banks were covered as well as big ones, at the instance of Steagall, over the objections of Glass.

* Former Utah banker Marinner Eccles, as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, re-engineered the governance of the Fed as part of the Banking Act of 1935, over the vigorous opposition of Carter Glass, who had been one of the architects of the original Federal Reserve Act. Eccles wrote later, “A more effective way of diffusing responsibility and encouraging inertia and indecision could not very well have been devised.”

Authority for monetary policy was re-assigned to the Board of Governors in Washington, in the form of a new 12-member Federal Open Market Committee, rather than left to the regional bank in New York. The power of the regional banks was reduced, and the appointment of their presidents made subject to the approval of the Board. Emergency lending powers were broadened to include what the governors considered “sound assets,” instead of previously eligible commercial paper, narrowly defined. The system remained privately owned, and required no Congressional appropriations (dividends from its portfolio of government bonds more than covered the cost of its operations), but its relationships with the Treasury Department and Congress remained somewhat ambiguous.

A fifth measure, the government’s entry into the mortgage business, has a cloudier history. The Federal Housing Act of 1934 set standards for construction and underwriting and insured loans made by banks and other lenders for home construction, but had relatively little effect until the Reconstruction Finance Corporation established the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, or Fannie Mae) in1938, to buy mortgage loans from the banks and syndicate them to large investors looking for guaranteed returns. With that, plus the design of a new 30-year mortgage requiring a low down payment, the housing market finally took off. As chairman of the Fed, Eccles pleaded with bankers to create the secondary market themselves, but without success.

Lawyers immediately began looking for loopholes. By 1940 they had found several, resulting in the passage of the Investment Company Act, providing for federal oversight of mutual funds, then in their infancy. Eight years later, the first hedge fund found a way to open its doors without supervision under the 1940 Act – as a limited partnership of fewer than 100 investors.

By the 1970s, many financial firm were eager to enter businesses forbidden them by the New Deal reforms. The little-remembered Securities Acts Amendment of 1975 began the process of financial deregulation with the seemingly innocuous aim of ending the 180-year-old prohibition of price competition among members of the New York Stock Exchange. It was a response to an initiative undertaken by the Treasury Department in the midst of the Watergate scandals of the Nixon administration, and signed into law by President Gerald Ford, Deregulation continued apace under President Jimmy Carter, and swung into high gear with the election of President Ronal Reagan. It reached its apex with the repeal of the key provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999.

As of 1975, financial innovators had been encouraged to experiment as they pleased, subject mainly to the discipline of competition. The moment coincided with developments in academic finance that revealed whole new realms of possibility. Fed regulators scrutinized the new developments at intervals. Investment banker (and future Treasury Secretary) Nicholas Brady headed a commission that examined relationships among commodity and stock exchanges after the sharp break in share prices in 1987. Economist Sam Cross studied swaps for the Fed. New York Fed President Gerald Corrigan undertook a more wide-ranging study of derivatives. Objections, including those of Brooksley Born, chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission from 1996-99, were swept aside.

An extensive new layer of regulation was put into place by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, after the collapse of the dot.com bubble and the corporate scandals of 2001, Enron, WorldCom and Tyco International, but mostly these had to do with corporate accounting practices and disclosure. The vast new apparatus of global finance worked pretty well, until unmistakable signs of stress began to show in the summer of 2007.

It will be years before the outlines of the 75 years between 1933, the trough of the Great Depression, and early 2008, the peak of the more-or-less uninterrupted global expansion that began in ’33 (making allowances for World War II and the ‘70s, when the U.S. drifted while Japan and other Asian economies grew rapidly) come into focus.

Yet a few basic facts about the period are already clear. Innovation was crucial, in finance as in all other things, especially information and communications technologies. Competition between the industrial democracies and the communist nations was a considerable stimulant to development. Banking and economic growth were intimately related, perhaps especially after 1975. And the dominant narrative furnished by economic science, the history of the business cycle compiled by the NBER, while valuable, is of limited usefulness when it comes to interpreting the history of events. Additional yardsticks will be required.

The New New Deal – Not

How did the Practicals do this time, measured against the template they chose, the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt? Not very well, I am sorry to say.

Certainly the Fed did much better than it had between 1928 and 1934. Decisions in its final years under Chairman Alan Greenspan will continue to be scrutinized. And no one doubts that Bernanke made a slow start after taking over in February 2006. But from summer of 2007, the Fed was on top at every juncture. The decision to let Lehman Brothers fail, is likely to be the chief topic of conversation in the stove-top league when his first-person account, The Courage to Act, appears next week. It will still be debated a hundred years from now.

If Lehman had somehow been salvaged, some other failure would have occurred. The panic happened in 2008. Bernanke, his team, and their counterparts abroad, were ready when it did.

The Bush administration, too, did far better than Hoover. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson was not so good in the thundery months after August 2007, when he pursued a will-o’-the-wisp he called a “super SIV (structured investment vehicle”), modeled on the private-sector resolution of the hedge- fund bankruptcies that accompanied the Russia crisis of 1998. And it can’t be said that the planning for a “Break-the-Glass” reorganization act that Paulson ordered in April produced impressive results by the time it was rolled out as the Troubled Asset Relief Program in September 2008. But Paulson’s team improvised very well after that. Bernanke and Paulson, Bush’s major post-Katrina appointments, as well as the president himself, with the cooperation of the congressional leadership, steered the nation through its greatest financial peril in 75 years.

The panic was nearly over by the time Obama took office.

In retrospect, the Obama admiration seems to have been either coy or obtuse in its first few months. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and Robert Rubin, the man he had succeeded in the job, formerly of Goldman Sachs and, by then, vice chairman of Citigroup, formally joined the Obama campaign on the Friday that the TARP was announced. (The connection to Rubin was soon severed.)

Summers, like the rest of the economics profession, began a journey of escape from the dogma he had learned in graduate school, which held that banking panics no longer occurred. Upon leaving office, in a conversation with columnist Martin Wolf, of the Financial Times, Summers hinted at how his thinking had changed when he told an audience at a meeting of the Institute for New Economic Thinking at Bretton Woods, N.H., in March 2011:

"I would have to say that the vast edifice in both its new Keynesian variety and its new classical variety of attempting to place micro foundations under macroeconomics was not something that informed the policy making process in any important way.''

Instead, Summers said, Walter Bagehot, Hyman Minsky, and, especially Charles Kindleberger had been among his guides to “the crisis we just went through.”

But Summers made little attempt that day to distinguish between the terrifying panic that occurred the September before Obama took office, and the recession that the Obama administration had inherited as a result. Nor did the accounts of Summers’s tenure subsequently published by journalists Noam Scheiber, Ron Suskind and Michael Grunwald make clear the extent to which the panic had been a surprise to Summers. Schooled to act boldly by his service in the Treasury Department during the crises of the ’90s, he did the best he could. At every juncture, Summers remained a crucial step behind Bernanke and Obama's first Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, the men he hoped desperately to replace.

The result was that Obama’s first address about the crisis, to a joint session of Congress, in February 2009, was memorable not so much for what the president said as for what he didn’t.

"I intend to hold these banks fully accountable for the assistance they receive, and this time they’ll have to fully demonstrate how taxpayer dollars result in more lending for the American taxpayer. This time, CEOs won’t be able to use taxpayer money to pad their paychecks or buy fancy drapes or disappear on a private jet.''

But there was no matter-of-fact discussion of the panic of the autumn before the election, in the manner of Franklin Roosevelt; no credit given to the Fed (and certainly none to the Bush administration); and not much optimism, either. The cost of inaction would be “an economy that sputters along not for months or years, perhaps a decade,” Obama said.

After an initial “stimulus” – as opposed to the “compensatory spending” of the New Deal – of the $819 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, inaction is exactly what he got. The loss of the Democratic majority in the House in the Tea Party election of 2010 only made the impasse worse. Yet the economy recovered.

Congress? Many regulators and bankers contend that the thousand-page Dodd Frank Act complicated the task of a future panic rescue by compromising the independence of the Fed. Next time the Treasury secretary will be required to sign off on emergency lending.

Bank Regulators? Some economists, including Gorton, worry that by focusing on its new “liquidity coverage ratio” the Bank for International Settlements, by now the chief regulator of global banking, will have rendered the international system more fragile rather than less by immobilizing collateral.

Bankers? You know that the young ones among them are already looking for the Next New Thing.

Meanwhile, critics left and right in Congress are seeking legislation that would curb the power of the Fed to respond to future crises.

So there is plenty to worry about in the years ahead. Based on the experience of 2008, when a disastrous meltdown was avoided, there is also reason to hope that central bankers will once again cope. Remember, though – it was a close-run thing.

David Warsh, a long-time financial journalist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com.

Robert Whitcomb: Those gratified by the Obamacare decision did not seem to worry that the court's conclusion

From all the cheering and hissing that greeted the Supreme Court's decisions about the Affordable Care Act -- "Obamacare" -- and same-sex marriage, it seemed as if the issues before the court were elections or even football games, not judicial matters, legal construction.

That has been the problem with appellate courts for some time now, their tendency to act as unelected legislatures, deciding policy, decisions properly cheered or hissed, rather than interpreting constitutions and laws, a dispassionate undertaking quite separate from policymaking.

In the "Obamacare" decision, even Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the court's majority sustaining the law, acknowledged that it was full of "inartful drafting" requiring the majority to reach for "context" elsewhere in the law so that "established by the state" could be construed to mean "established by the state or federal government." To prevent a vast, new edifice of government from collapsing abruptly under its flaws, the court's majority decided that the law didn't really mean what it said.

Those gratified by the Obamacare decision did not seem to worry that the court's conclusion -- that laws don't always mean what they say -- might someday be invoked to their disadvantage.

As for same-sex marriage, public attitudes have changed dramatically in its favor. Laws against same-sex intimacy long have been invalidated as invasions of privacy, based only on arbitrary religious objections, and there is little in marriage that same-sex couples have not been able to arrange through ordinary contract law.

Much if not most of the argument against same-sex marriage arises only from those arbitrary religious objections, which aren't really arguments at all.

As a practical matter lately the issue has been only whether all governments and commerce should have to ratify homosexuality.

But the weakness of the argument against same-sex marriage as policy has nothing to do with whether the Constitution requires states to authorize it. Further, equal protection claims for a constitutional right to same-sex marriage are themselves weak, since no person or class was being denied the right to marry. Everyone was free to marry someone of the opposite sex, even if sexual identity itself lately seems to have fallen into question.

The same-sex marriage case may have been a good example of the conflict between the two major schools of constitutional law, the "originalist" and the "living constitution" schools.

The originalists hold that constitutions must be interpreted to mean what they meant at the time of their enactment, or else they aren't really constitutions at all. The advocates of a "living constitution" hold that constitutions should be adapted to new circumstances without formal amendment through the democratic process, the adaptation done by judges, largely unelected.

Through the years political liberals and conservatives have inhabited both schools, but small-d democrats tend to favor the originalist school, while totalitarians everywhere favor the "living constitution" school, for reasons Lewis Carroll, in "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland," explained as well as anyone has explained them in the 150 years since:

"When I use a word," Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean -- neither more nor less."

"The question is," said Alice, "whether you can make words mean so many different things."

"The question is," said Humpty Dumpty, "which is to be master -- that's all."

The "Obamacare" and same-sex marriage decisions suggest that Justice Dumpty would feel right at home on the Supreme Court.

Back in menacing Minnesota

As tends to happen more as one ages, I've been thinking about my familial origins lately. This photo (my friend Philip Terzian is in the picture) is of the front of the house that Scott Fitzgerald lived in on Summit Avenue, in St. Paul, Minn. The street is rich with Victorian and Edwardian residential architecture.

The Terzians sent it to me after I noted that my maternal grandmother lived on the street, Around the turn of the last century, her father was the co-owner of a "carriage-trade'' Minnesota department store called Panton & White that sold fancy goods, such as Limoges plates, and more routine things, too. (His name was William Dale White.)

They started in St. Paul-Minneapolis -- lots of grain-milling and railroad money! Robber Barons galore!

They ended up in mostly in Duluth, lured there by the money to be made as a result of the gigantic iron-ore range a bit inland and the access to points east via the port of Duluth and its sister city, Superior, Wis.

They made a lot of money for a while, but some in the family, including my great-grandfather, had powerful urges toward self-destruction, including alcoholism -- like their former neighbor Scott Fitzgerald. And some bad luck.

All of my grandmother's four siblings were dead before she was 30, including her brother, stabbed to death soon after he graduated from Princeton. (I'm told he wrote poetry.) The others died from the flu, a fire and one of Minnesota's earliest fatal car crashes.

No wonder my grandmother often looked terrified when her phone rang.

-- Robert Whitcomb

The torments of the privileged

I get a kick out of reading about the torments of the rich and prestige-status-and-name-dropping-obsessed Anne-Marie Slaughter and her husband as they strive to tell us what deeply sensitive and sacrificing Yuppie parents they are. Maybe if Ms. Slaughter would less time promoting herself in the media as a world-historical expert on upscale-family values she'd have more time to spend with her teenage sons.

Her latest book is Unfinished Business: When Working Families Can't Do It All. This follows her famous magazine article "Why Women Still Can't Have it All".

Who can -- even someone with all the spoiling privileges that Ms. Slaughter has had?

Will she protest along these lines when the Grim Reaper shows up at her doorstep?

-- Robert Whitcomb

Fall killing season nears

Don Pesci: Is the Pope Catholic?

It would suit progressives, for instance, if the pope would be so good as to repeal thousands of years of Catholic teaching on abortion. No matter the pope of the moment, this will happen only when Hell freezes over. But progressives welcome the present pope’s views on climate change and capital punishment, while on the right, such views are anathema.

Pope Francis’s antipathy toward raw capitalism cheers such as socialist Bernie Sanders, who is running for president this year, as well as President Obama, who, during welcoming ceremonies at the White House, extravagantly praised the pope on his resemblance to himself. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery but, however flattering, imitation falls far short of self-praise, which is always intensely sincere.

A master at co-opting moments, Mr. Obama gave it his best shot. As a community organizer in Chicago early in his political career, Mr. Obama told the 11,000 guests gathered on his lawn to hear the pope, he had worked with the Catholic Church to bring hope and change to the poor.

“Here in the United States, we cherish our religious liberty,” Mr. Obama said, but around the world, at this very moment, children of God, including Christians, are targeted and even killed because of their faith.”

Perhaps from a sense of delicacy, Mr. Obama did not identify the chief persecutors of Christians in the world. ISIS, a confederation of Islamic terrorists, has been particularly oppressive. The beheading of Christians, the burning of Christian churches, the rape and enslavement of Christian women never occurred in Chicago when Mr. Obama was evangelizing on its mean streets.

The pope acknowledged that “American Catholics are committed to building a society which is truly tolerant and inclusive, to safeguarding the rights of individuals and communities, and to rejecting every form of unjust discrimination. With countless other people of good will, they are likewise concerned that efforts to build a just and wisely ordered society respect their deepest concerns and the right to religious liberty. That freedom remains one of America’s most precious possessions.”

As if to underscore his remarks concerning religious liberty, the pope on Wednesday made what is being called “an unscheduled stop” to a convent of nuns, The Little Sisters of the Poor, “to show his support for their lawsuit against U.S. President Barack Obama’s healthcare law.” Vatican spokesman Father Federico Lombardi characterized the unscheduled stop as a “brief but symbolic visit.”

Congress doubtless was pleased to host the pope and listen to his message, but the Holy Father did not dine with Congressional leaders after the presentation, because the keeper of the pope’s schedule already had booked him for lunch with the poor in Washington D.C.

Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy, who describes himself as “a non-practicing Catholic,” was stirred by certain portions of the pope’s remarks. We should not let Mr. Malloy’s self-characterization pass without noting that since Catholicism is largely a praxis, there is little difference between “a non-practicing Catholic” and a non-Catholic. Receiving the Pope with 11,000 others on the south lawn of the White House, Mr. Malloy said, was an “amazing” and “moving” experience for him.

According to one paper, Mr. Malloy had “embraced the progressive movement within the Catholic church known as liberation theology. Believers of the movement felt it wasn’t enough to simply care for the poor, but felt it was necessary to pursue political changes to eradicate poverty.”

The pope, Mr. Malloy told the paper, “seems to be inviting that back.” Not true. This pope and others – most dramatically, Pope John Paul II, who was canonized in 2014 – sternly rejected liberation theology, a theological-political movement in the Latin American of the 1970’s that attempted to combine Catholicism with revolutionary socialism, but then one cannot expect part-time Catholics to be current with the theological niceties of their church.

The pope is much more interested in liberty than in liberation theology. He holds, along with Catholics throughout the ages, that true freedom is attained through a love of the good and beautiful, whose exemplar is the Christ of Holy Scripture. All of us will do well to remember that popes are not presidents or congressmen or governor, for which we should all drop to our knees and thank God. The pope’s kingdom, like that of the Christ he serves, is in some sense not of this world.

Don Pesci (donpesci@att.net) is a political writer who lives in Vernon, Conn.

Llewellyn King: The Nasty Magic of the Market

The late, great neo-classical version of Pennsylvania Station, whose construction was completed in 1910. The grand structure was torn down in 1963, to be replaced by the claustrophobic current version.

As architectural historian Vincent Scully wrote: "One entered the city like a god {with the old Penn Station}. One scuttles in now like a rat.''

The market is a wondrous place. It ensures you can drink Scotch whisky in Cape Town and Moscow, or Washington and Tokyo, if you prefer. It distributes goods and services superbly, and it cannot be improved upon in seeking efficiency.

But it can’t think and it can’t plan; and it’s a cruel exterminator of the weak, the unready or, for that matter, the future.

Yet there are those who believe that the market has wisdom as well as efficiency. Not so.

If it were wise, or forward-looking, or sensitive, Mozart wouldn’t have died a pauper, and one of the greatest — if not the greatest architecturally — railway station ever built, Penn Station, wouldn’t have been demolished in 1963 to make way for the profit that could be squeezed out of the architectural deformity that replaced it: the Madison Square Garden/Penn Station horror in New York City.

Around Washington, Los Angeles and other cities are the traces of the tracks of the railroads and streetcar lines of yore. These were torn up when the market anointed the automobile as the uber-urban transport of the future. As Washington and Los Angeles drown in traffic, many wish the tracks — now mostly bike paths — were still there to carry the commuter trains and streetcars that are so badly needed in the most traffic-clogged cities.

Now the market, with its concentration on the present tense, is about to do another great mischief to the future. An abundance of natural gas is sending the market signals which threaten carbon-free nuclear plants before their life is run out, and before a time when nuclear electricity will again be cheaper than gas-generated electricity. World commodity prices are depressed at present, and no one believes that gas will always be the bargain it is today.

Two nuclear plants, Vermont Yankee in Vernon, Vt. , and Kewaunee in Carlton, Wis., have already been shuttered, and three plants on the Exelon Corp. system in the Midwest are in jeopardy. They’ve won a temporary reprieve because the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) says the fact that they have round-the-clock reliability has to be taken into account against wind and solar, which don’t. In a twist, solar and wind have saved some nuclear for the while.

Natural gas, the market distorting fuel of the moment, is a greenhouse gas producer, although less so than coal. However gas, in the final analysis, could be as bad, or worse, than coal when you take into account the habitual losses of the stuff during extraction. Natural gas is almost pure methane. When this gets into the atmosphere, it’s a serious climate pollutant, maybe more so than carbon dioxide, which results when it is burned.

Taken together — methane leaks with the carbon dioxide emissions — and natural gas looks less and less friendly to the environment.

Whatever is said about nuclear, it’s the “Big Green” when it comes to the air. Unlike solar and wind, it’s available 24 hours a day, which is why three Midwest plants got their temporary reprieve by the FERC in August.

When President Obama goes to Paris to plead with the world for action on climate change in December, the market will be undercutting him at home, as more and more electricity is being generated by natural gas for no better reason than it’s cheap.

As with buying clothes or building with lumber, the cost of cheap is very high. The market says, “gas, gas, gas” because it’s cheap – now. The market isn’t responsible for the price tomorrow, or for the non-economic costs like climate change.

But if you want a lot of electricity that disturbs very little of the world’s surface, and doesn’t put any carbon or methane into the air, the answer is nuclear: big, green nuclear.

Llewellyn King (lking@kingpublishing.com) is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a longtime publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant.

— For InsideSources.com

We look funny to it

Joyce Rowley: Community outreach to warn of toxic fish

On a recent summer weekend, community outreach worker Genero Mendez talked to 17 people, mostly families, about the risks of eating the fish they were catching in New Bedford Harbor. He visits the city’s South End fishing spots to educate people who may not realize that the fish they are catching are contaminated with polychlorinated biphenols (PCBs).

“Some people don’t know the fish is contaminated or the risk. They’re just catching a meal,” Mendez said. “Some people say, “I’ve been fishing here for 18 years, and I'm still alive.’ I explain it’s like smoking — you won't get sick now, but later you will.”

Mendez, who speaks Spanish, and Mayan K'iche, along with Joao Verissimo and Julio Suar, were hired for the summer as multilingual outreach coordinators by the Community Economic Development Center (CEDC) under a $7,000 grant from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to the city’s department of Environmental Stewardship.

The EPA, the city and the CEDC partnered to create the 12-week outreach project, as part of the Community Involvement Plan and clean up of New Bedford Harbor, an EPA Superfund site.

“Our goal is to educate people fishing in the harbor so they can make the best decision in feeding their families,” said Kelsey O'Neill, an EPA community involvement coordinator.

The community involvement plan for the Superfund site cleanup also includes public meetings, public service announcements and working with local stakeholders to develop new ways to get the word out about the extent of the harbor’s contamination.

Michele Paul, the city’s director of environmental stewardship, said there are signs but no mechanism to prevent people from fishing in the harbor.

“That’s why outreach and education is so important, especially for the immigrant community who fish for sustenance,” she said.

Paul noted that the city’s Health Department inspects local restaurants to ensure no harbor fish or shellfish reaches customer tables. New Bedford’s commercial fishermen fish offshore, not in the harbor.

New Bedford, a city of 95,000, has a poverty rate of 23 percent and more than a third of the population speaks a language other than English at home, according to the 2010 U.S. Census. An estimated 8,000 to 10,000 undocumented immigrants live in New Bedford.

“A lot of the fishermen are newcomers and are not aware of the risks,” said Corinn Williams, CEDC’s executive director. “People are very appreciative in learning there are these risks.”

Mendez goes out as early as 5:30 in the morning to reach people while they’re out fishing. He explains the outreach program, distributes brochures in Spanish, Portuguese and English that outline EPA recommendations, and collects data via questionnaires.

"The questionnaire gathers information on how often they fish or consume fish caught in the harbor, and whether they were aware of the health concerns,” Williams said.

Since toxic chemicals were first discovered in the harbor in 1987, the EPA has recommended against consuming any fish in Area 1, north of the hurricane barrier. Outside the barrier in Area 2 between Sconticut Neck and Ricketsons Point, EPA recommends against eating lobster and bottom-feeding fish.

In 2010, the recommendation for Area 2 changed, to allow one meal of black sea bass or one meal of shellfish other than lobster per month. In Area 3, from the end of West Island to Mishaum Point known as the Outer Harbor, lobster and scup are still prohibited, but one meal a month of black sea bass is allowed.

EPA recommends against consumption of fish by pregnant or nursing women and children younger than 12 in all three areas, with the exception of one shellfish meal a month from the Outer Harbor.

“In six years the clean up will be done,” O’Neill said. “But it will take some time before the organic life of the harbor floor is free of PCBs. It will stay in the food chain as well. Our goal is to clean the site so it will be fishable.”

“People come from Guatamala, Honduras, El Salvador, Portugal,” Mendez said. “I'm happy that I’m helping the community.”

John O. Harney: Talking about cures at the BIF

Last week, I was at Providence’s Trinity Rep covering BIF2015, the Business Innovation Factory's summit of innovators. It was BIF’s 11th summit, my fifth as a guest. I was attending under a quasi-media category called RCUS, standing for the BIF mantra of “Random Collisions of Unusual Suspects.”

BIF founder and "chief catalyst" Saul Kaplan opened the talks by noting that earlier in the week was the Jewish New Year, based on the Book of Life. That book is not closed. We can keep writing it by how we treat each other. A perfect opening for what was to come ...

Parked in front of the historic Trinity Rep was a food truck. It was Julius Searight’s Food4Good truck. A so-called “crack baby,” it is actually unrelated cerebral palsy that has left him with deficiencies in fine motor skills and slow speech. He told of living in foster care, getting adopted and reading far below grade level as a youngster. But that can’t hide the passion. He eventually went to Johnson and Wales University and got a degree in food service and, after spending time with AmeriCorps, started the nonprofit Food4Good. His idea was to bring food to poor neighborhoods, so residents there don’t have to trudge to soup kitchens. Food4Good sells comfort food to those who can afford it, but also donates thousands of free meals to the needy.

Searight got a standing O. But other BIF speakers got heartfelt applause too.

Brain waves

Steven Keating is a doctoral candidate in mechanical engineering at MIT, who works out of MIT’s Media Lab. In 2007, Keating, a self-described nerd, volunteered for an MRI mostly out of curiosity. The MRI revealed an abnormality, but doctors thought it was just something to keep an eye on. By 2014, he complained of a vinegary smell … interesting since the abnormality was near the part of the brain that controls olfactory senses. Another MRI showed that the tumor had grown to the size of a baseball. It was removed during “awake brain surgery.” Keating asked the doctors to videotape it. Three days later, he was back on campus and more determined than before to help patients collect and understand their health data.

At BIF, Keating showed videos of the brain surgery as well as a detailed map of his genome sequence, including the problem in the code. In the future, he wondered, could med students dissect themselves? Could they share images with researchers and others via medical selfies and crowdsource solutions? Why is it so hard for patients to get their own medical data, including genome maps? Why don’t hospitals have “share” buttons, to help patients determine the best course of treatment?

As a child, Matthew Zachary dreamed of being a concert pianist. At age 21 as a college senior and composer, he noticed his hand wasn’t working. He was diagnosed with pediatric brain cancer and told he'd probably not survive six months and would never perform again. After his surgery, he wrote two CDs worth of music as if to defy those who told him he’d never be able to write music again. Zachary’s Stupid Cancer organization focuses on challenge facing 15- to 30-year-olds who have been diagnosed with cancer. It’s an age group that tends to be overlooked by cancer organizations focused on people at the two ends of the life spectrum. It’s a group that has age-appropriate challenges in terms of relationships, fertility and careers, And most of all isolation. Stupid Cancer brings them together. Incidentally, Zachary became the concert pianist he dreamed of being before the cancer.

Share and tell

Zipcar founder Robin Chase explained that in the past, when you bought a car or rented one, you were paying for a lot of time that the car was not actually being used. This “excess capacity” is what fuels the so-called sharing economy, which ascended with brands like Chase’s Zipcar and Airbnb. Chase asserted that peer collaborators are not consumers as much as co-creators. Her new book Peers Inc: How People and Platforms Are Inventing the Collaborative Economy and Reinventing Capitalism flies in the face of the old advice to get a good job with benefits. Chase’s premise combines the best of people power with the best of corporate power. More networked minds are better than fewer proprietary minds. The benefits of sharing via open assets outweigh problems with sharing. (Nonetheless, the sharing economy has faced criticisms of late.)

Joshua Davis was working as a data-entry clerk when he noticed that if he keyed in something wrong, the machine beeped. As if it knew. So what was he doing there? Seeking something different, he went off to the U.S. arm wrestling championship in Laughlin, Nev. He came in 4th in the lightweight division. Fourth out of four. Good enough to make the U.S. team and travel to the world championship in Poland. Someone suggested that he write about the experience for a magazine, noting that the field has a fairly low barrier to entry. Suddenly Davis became a journalist just as suddenly as he’d become an arm wrestler. During run-up to the Iraq war, he offered to go to Iraq for Wired magazine as a war correspondent.

He also covered a group of undocumented Latino students from a high-poverty school in Phoenix as they designed an underwater robot out of scavenged parts that ended up beating the ExxonMobil-sponsored entry from MIT in the robot finals. His book about it called Spare Parts has been made into a movie with Jamie Lee Curtis, George Lopez and Marisa Tomei. And Davis has started a new publishing venture called EPIC True Stories and is a co-founder of Epic Magazine, publishing long-form true stories.

Crime and redemption

Moore’s Law suggests that computer power doubles every two or so years. The counterpart is Moore’s Outlaws, says security expert Marc Goodman. Criminals had cellphones before cops did, said Goodman, who has worked with the UN and Interpol. One challenge for the criminals was how to (in BIF parlance) scale up. Now drug cartels in Mexico have entire cellphone networks. Crime is fully automated. Criminal algorithms can carry out crimes. We have crimebots, but not copbots. The Target retail hack robbed 100 million people of personal info. An estimated 50 billion new devices will be on the Internet by 2030. Goodman warns that the so-called Internet of Things will just mean more to hack.

To illustrate his point, Goodman showed a 60 Minutes clip of a car’s operations being hijacked by a hacker via remote control. Moreover, he said, drones have been used to drop materials into prison yards and even spy on rival drug dealers. He showed one drone photo of a London apartment window lit up where tenants were growing pot. There is opportunity for one person to commit exponential good or exponential harm, concluded Goodman.

Catherine Hoke asked the BIF audience: “What would it be like if I was only known for the worst thing I’ve done?”

America, she said, is often not the land of second chances. Hoke pointed out that 30% of 23-year-olds already have a criminal record and 70% of children with incarcerated parents follow in their footsteps.

While earning about $200,000 at a New York City venture-capital firm, Hoke had the chance to visit a prison in Texas. She learned that a lot of incarcerated people had similar profiles as people in the BIF audience, including experience with sophisticated governance, bookkeeping and marketing (but were perhaps not so good at risk management, she joked, insofar as they got arrested). Hoke wondered what would happen if inmates applied those talents to entrepreneurship.

She started the Prison Entrepreneurship Program (PEP) to help them do it. Under 5% of ex-offenders in PEP returned to prison within three years of release, compared with more than 40% nationally. Hundreds of PEP alumni started businesses.

Hoke returned to the theme of being haunted by the worst thing you’ve ever done. For her, it was relationships she had with some PEP graduates after a difficult divorce. She wrote to PEP people telling them about the poor choices she had made. She tried to kill herself. But in response to her confession, Hoke got thousands of emails of support. She realized people could love her as a human being, not just a machine that produces results. The venture capital firm offered her job back. She turned it down and created Defy Ventures to help people with criminal histories use their innate entrepreneurial skills to create sustainable, legal enterprises.

The recidivism rate for Defy’s entrepreneurs in training is 3%. They’re transforming their hustle into startups. Two Defy grads joined Hoke on stage, the man is CEO of ConBodym which employs formerly incarcerated people as trainers who teach the toughest prison style boot camp classes; the woman is CEO of a soul food truck. Hoke left behind a T-shirt that says “Hustle Harder.”

Dennis Whittle quipped that he was an ex-offender too: He spent 14 years at the World Bank. When told by his assistant that he was booked to speak at BIF, Whittle groused about what to speak on. Someone suggested that he prep by reading his bio. He did, and was struck by how good it was, including certainly his stint leading GlobalGiving, the largest global crowdfunding community for nonprofits, which was launched by the World Bank. But when Whittle realized he’d be in a lineup with cancer survival and other deep personal stories, he realized his resume is not how his life has actually felt. He explained that despite trips to exotic places such as Burma, his best time in the past year was touring coalmines and hills with his old friends from West Virginia. They wouldn’t know anything about subjects like BIF or crowdfunding.

But that connection says more about his life than his resume could. Saul Kaplan noted how different our resumes are from our lives. It’s a perennial BIF theme recently labeled by columnist David Brooks as resume virtues vs. eulogy virtues.

Overcoming obstacles

Jeff Sparr was ecstatic when his son hit a home run in a big Little League game. But Jeff couldn’t celebrate. He was having a panic attack. A manifestation of the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) that creates attacks based on thoughts of his failure. Failure as a husband, as a father, you name it. It robs him of great memories like that round-tripper. Twenty years ago, someone told him painting might help. He painted and painted and painted. And he realized he felt better. He started giving his art away, when a friend told him it was not a good business model. When he sold $15,000 worth of art a few weeks later, he went to a children’s psych unit where he served on the board and had been a patient and delivered paints, brushes and canvasses ... and told his story. Sparr is another who’s scaling up. He created PeaceLove Studios in Rhode Island to train people to bring peace of mind to thousands of people.

Sophie Houser is a freshman at Brown University. She was involved in an organization called Girls Who Code, whose mission is address the gender gap in the tech and engineering sectors. Women make up half of the U.S. workforce, but just 25% of tech and computing jobs. Houser invented a videogame that addresses this and another crisis: self-consciousness among girls about menstruation. In the game called Tampon Run, girls throw tampons—which, Houser reasoned, should not be any more objectionable than the blood of shoot-them-up games. Back to coding, Houser told of how difficult it was to make the girl in the game jump up for a new box of tampons—the clichéd videogame gimmick to reload. Ultimately, she found 10 lines of code to make the girl jump.

Media outlets around the world picked up the story and, Houser and her co-inventor went to Silicon Valley and began working on a biopic. More importantly, said Houser, users said the game made periods feel normal … and some said they were inspired to code.

Tanisha Robinson calls herself an ultra-minority: gay, black, Mormon. She went to Brigham Young University, then joined the U.S. Army because she thought it was more tolerant. She became an Arabic linguist, but was kicked out under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, when she told. Then she went to Ohio State. Then Damascus to teach English. Then she returned to Columbus, Ohio, to form an organization called Print Syndicate. Her outfit sells T-shirts and other goods on the Internet branded with offbeat expressions for introverts to express social identity. Robinson says she watches out for marginalized groups. “We believe in equal pay so we pay all men 70 cents on the dollar,” she joked.

BIF likes to add some music to liven up the proceedings. Singer-songwriter and guitarist Dani Shay sang “Girl Or Boy” … a question many people were asking about Dani online. Why do they care? she asked. Shay jokes about how Justin Bieber emerged around the same time and looked a lot like Dani. Then she sang an upbeat too-happy tune mocking “all I want to be is on the radio,” following by one that she really does want to be on radio to help change the world. It’s poppy. Got the audience clapping.

Art of innovation

When Barnaby Evans came to Providence, he was stunned by how negative the people were about the city. He showed the BIF crowd slides of Mohawked hipsters on the one hand and an aging white crowd at an art forum on the other. The art world is siloed. Evans attacked both problems with his invention of Providence’s WaterFire art installation 21 years ago. All are invited. No tickets needed, Barnaby noted that a group of nuns from New Hampshire and a group of Hell’s Angels both came to a recent WaterFire, That’s a symbol of two different types of art audiences. He concluded fittingly with video of a funeral procession plying the river at WaterFire.

So much at BIF celebrates the new and spontaneous. Chris Emdin, associate prof at Teachers College at Columbia University and co-creator of #HipHop Ed, reminded the audience of the importance of things we’ve been doing a long time. For example, there’s a reason Serena Williams can be seen practicing tennis as a 5-year-old in Compton. In his work to get more young people interested in STEM, Emdin thinks back to growing up in the Bronx and seeing Black America in Stevie Wonder’s Innervision andSongs of the Key of Life. The morning of the BIF talk, news broke of a 14-year-old Ahmed Mohamed of Texas being arrested because he brought a homemade clock into school and it was mistaken as a bomb. As a kid, Emdin worshiped Wu-Tang Clan and its disruption of the Grammy awards 10 years before Kanye West stormed the stage on Taylor Swift. Emdin was fascinated when a Wu-Tang Clan member GZA came to campus as a scientist. The two collaborated on a program mixing hiphop and science education for middle and high school students.

Mezzo-soprano Carla Dirlikov grew up in Michigan, the daughter of a Bulgarian father and Mexican mother. The parents never spoke a common language, so Carla learned both of their native languages and translated for them, And boy, can she sing? She delivers a beautiful opera with an accompanying pianist. Says she’s in search of duende like Lorca. (Or like George Frazier?) Opera, she reminded the BIF audience, allows the voice to focus on peaks and abysses.

Barry Svigals is an architect. Among designs by Svigals was a school in New Haven, Conn., which became the prototype for schools everywhere from 1996 forward. At BIF, he segued to a sign “We are Sandy Hook. We choose love.” He cited a friend, a former New Yorker editor who died and had stipulated that his memorial service include ponies and ice cream—a sensibility he worked into the Sandy Hook site.

Kimberly Kleiman-Lee is responsible for leadership development at GE, a company of 310,000, including 6,000 who Kleiman-Lee works with who are “responsible for shaping GE’s future.” Before she arrived, GE ran leadership meetings from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. in a room with no windows called the Pit. Kleiman-Lee created a massive sign in the style of a ransom note inviting leaders to go to a different room where their advice would be heard. She changed the vibe. The staff began serving meals family style among leaders. They brought them to Normandy and connected the daunting battle in front of the GIs with those they face at GE (and all with a straight face presumably). The No. 1 rule for corporate innovators, said Kleiman-Lee, is to give yourself permission to be fired.

Carlos Moreno, a former teacher at the Met School in Providence, is now director of Big Picture Learning. He grew up in the Bronx about five blocks from Fordham University, but had never stepped foot on the campus. He was a typical student athlete, he said, doing just well enough to remain eligible. Then one day, he was pistol-whipped and robbed for an $89 Cincinnati Bengals jersey. He knew that he should’ve gone onto the Fordham campus for help, but that felt like trespassing. His law-abiding parents from the Caribbean went and filed a report with police, but he knew there’d be no justice. His teachers and coaches were supportive, but none of them came from where he did, so could only offer limited help. There was no intervention before being thrown back into class.

At BIF, Moreno proposed addressing inequality with innovation. Schools are offering a politically correct but destructive approach that offers only one path to success. Big Picture Learning helps students find their niche and says it’s OK if they have different results. It’s OK for students to become “self-directed” and assess their own work. His advice: 1) pay attention to the whole child (including challenges and community issues); 2) pay attention to student strengths, not weaknesses; 3) be innovative in authentic assessments, so students demonstrate what they know; and 4) let students apply what they learn outside the school.

Big Picture Learning has launched a “relentlessly student-centered” Deeper Learning Equity Fellows for every student.